Those things are better which are perfected by nature than those which are finished by art.

—Cicero, 45 BCAsking for Particulars

Thomas Jefferson’s instructions for Lewis and Clark.

To Meriwether Lewis, esquire, Captain of the First Regiment of Infantry of the United States of America:

The object of your mission is to explore the Missouri River, and such principal streams of it, as by its course and communication with the waters of the Pacific Ocean—whether the Columbia, Oregon, Colorado, or any other river—may offer the most direct and practicable water communication across this continent for the purposes of commerce.

Beginning at the mouth of the Missouri, you will take observations of latitude and longitude at all remarkable points on the river, and especially at the mouths of rivers, at rapids, at islands, and other places and objects distinguished by such natural marks and characters of a durable kind, as that they may with certainty be recognized hereafter. The courses of the river between these points of observation may be supplied by the compass, the log-line, and by time, corrected by the observations themselves. The variations of the needle, too, in different places should be noticed.

The interesting points of the portage between the heads of the Missouri and of the water offering the best communication with the Pacific Ocean should also be fixed by observation, and the course of that water to the ocean in the same manner as that of the Missouri.

The commerce which may be carried on with the people inhabiting the line you will pursue renders a knowledge of those people important. You will therefore endeavor to make yourself acquainted, as far as a diligent pursuit of your journey shall admit, with the names of the nations and their numbers; the extent and limits of their possessions; their relations with other tribes or nations; their language, traditions, monuments; their ordinary occupations in agriculture, fishing, hunting, war, arts, and the implements for these; their food, clothing, and domestic accommodations; the diseases prevalent among them and the remedies they use; moral and physical circumstances which distinguish them from the tribes we know; peculiarities in their laws, customs, and dispositions; and articles of commerce they may need or furnish, and to what extent.

And considering the interest which every nation has in extending and strengthening the authority of reason and justice among the people around them, it will be useful to acquire what knowledge you can of the state of morality, religion, and information among them; as it may better enable those who endeavor to civilize and instruct them to adapt their measures to the existing notions and practices of those on whom they are to operate.

Other objects worthy of notice will be the soil and face of the country, its growth and vegetable productions, especially those not of the United States; the animals of the country generally, and especially those not known in the United States; the remains and accounts of any which may be deemed rare or extinct; the mineral productions of every kind, but more particularly metals, limestone, pit coal, and saltpeter; salines and mineral waters, noting the temperature of the last, and such circumstances as may indicate their character; volcanic appearances; climate, as characterized by the thermometer, by the proportion of rainy, cloudy, and clear days, by lightning, hail, snow, ice, by the access and recess of frost, by the winds prevailing at different seasons; the dates at which particular plants put forth, or lose their flower or leaf; times of appearance of particular birds, reptiles, or insects.

In all your intercourse with the natives, treat them in the most friendly and conciliatory manner which their own conduct will admit; allay all jealousies as to the object of your journey; satisfy them of its innocence; make them acquainted with the position, extent, character, peaceable and commercial dispositions of the United States, of our wish to be neighborly, friendly, and useful to them, and of our dispositions to a commercial intercourse with them; confer with them on the points most convenient as mutual emporiums and the articles of most desirable interchange for them and us. If a few of their influential chiefs within practicable distance wish to visit us, arrange such a visit with them, and furnish them with authority to call on our officers on their entering the United States, to have them conveyed to this place at the public expense. If any of them should wish to have some of their young people brought up with us, and taught such arts as may be useful to them, we will receive, instruct, and take care of them. Such a mission, whether of influential chiefs or of young people, would give some security to your own party. Carry with you some matter of the kinepox; inform those of them with whom you may be of its efficacy as a preservative from the smallpox, and instruct and encourage them in the use of it. This may be especially done wherever you winter.

Should you reach the Pacific Ocean, inform yourself of the circumstances which may decide whether the furs of those parts may not be collected as advantageously at the head of the Missouri (convenient as is supposed to the waters of the Colorado and Oregon or Columbia) as at Nootka Sound or any other point of that coast; and that trade be consequently conducted through the Missouri and United States more beneficially than by the circumnavigation now practiced.

On your arrival on that coast, endeavor to learn if there be any port within your reach frequented by the sea vessels of any nation, and to send two of your trusty people back by sea, in such way as shall appear practicable, with a copy of your notes; and should you be of opinion that the return of your party by the way they went will be imminently dangerous, then ship the whole and return by sea, by the way either of Cape Horn or the Cape of Good Hope, as you shall be able. As you will be without money, clothes, or provisions, you must endeavor to use the credit of the United States to obtain them; for which purpose open letters of credit shall be furnished you, authorizing you to draw on the executive of the United States, or any of its officers, in any part of the world on which draughts can be disposed of, and to apply with our recommendations to the consuls, agents, merchants, or citizens of any nation with which we have intercourse, assuring them in our name that any aids they may furnish you shall be honorably repaid, and on demand. Our consuls, Thomas Hewes at Batavia in Java, William Buchanan in the Isles of France and Bourbon, and John Elmslie at the Cape of Good Hope, will be able to supply your necessities, by draughts on us.

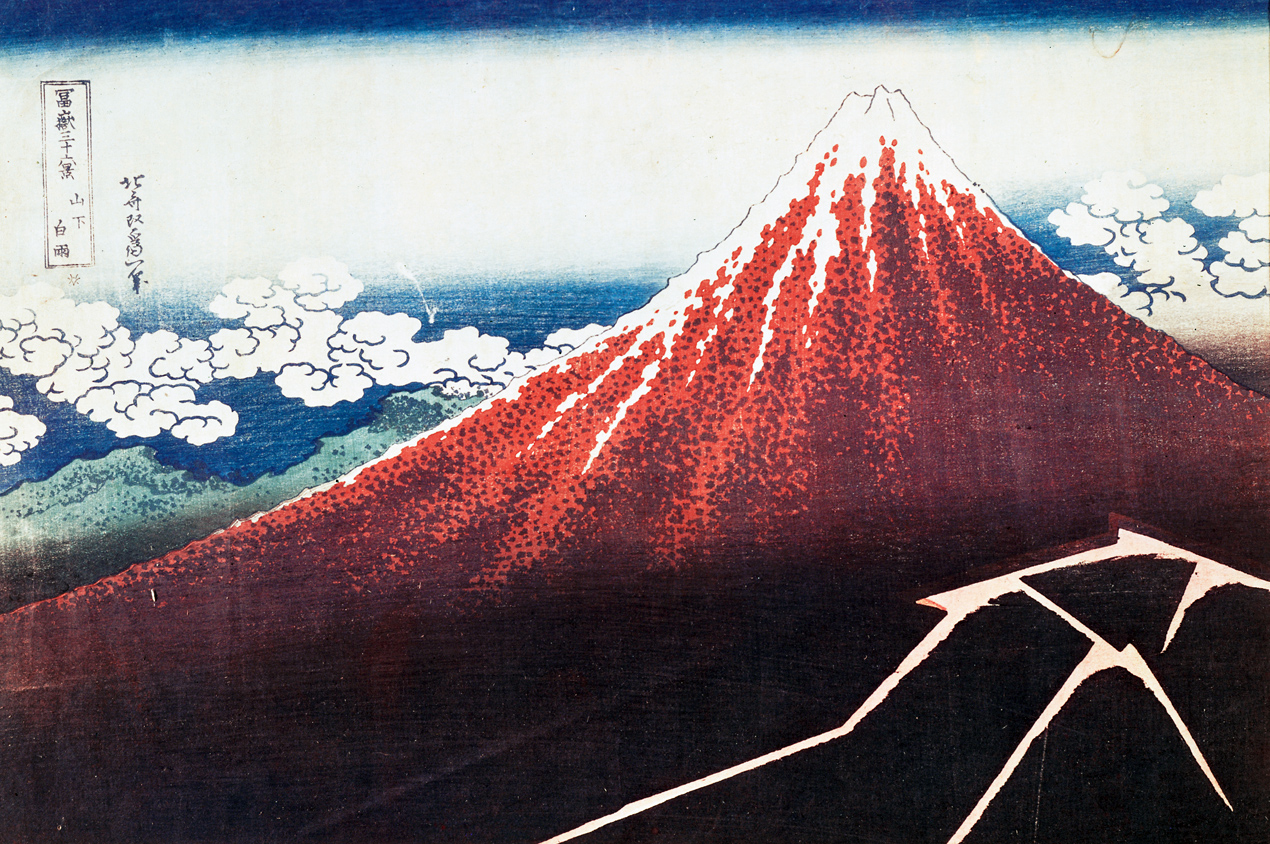

Lightning on Mount Fujiyama, by Katsushika Hokusai, c. 1823. Art Institute of Chicago, Illinois.

Should you find it safe to return by the way you go, after sending two of your party round by sea, or with your whole party if no conveyance by sea can be found, do so; making such observations on your return as may serve to supply, correct, or confirm those made on your outward journey.

On reentering the United States and reaching a place of safety, discharge any of your attendants who may desire and deserve it, procuring for them immediate payment of all arrears of pay and clothing which may have incurred since their departure, and assure them that they shall be recommended to the liberality of the legislature for the grant of a soldier’s portion of land each, as proposed in my message to Congress, and repair yourself with your papers to the seat of government.

Given under my hand, at the city of Washington, this twentieth day of June 1803.

Thomas Jefferson,

President of the United States of America

Thomas Jefferson

From a letter to Meriwether Lewis. In January 1803, Jefferson had made a secret request to Congress for $2,500 to finance an exploration of the Missouri River. That May, the United States paid Napoleon $11 million for the Louisiana Purchase. An amateur paleontologist, Jefferson expected Lewis to find, in addition to a trade route to the Pacific Ocean, woolly mammoths.