Language is the house of being. In its home human beings dwell. Those who think and those who create with words are the guardians of this home.

—Martin Heidegger, 1949Native Tongues

The making of the Dictionary of American Regional English, a five-thousand-page, five-volume book documenting the history of American slang.

By Simon Winchester

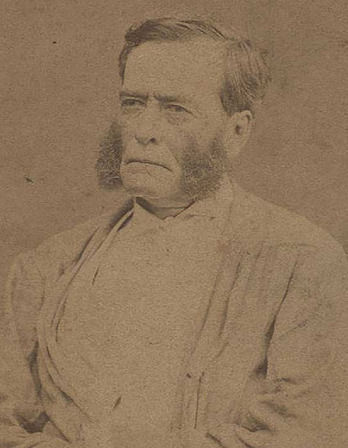

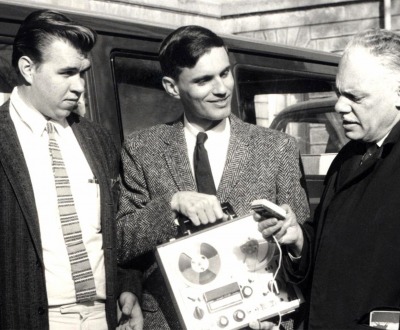

Dictionary of American Regional English chief editor Frederic G. Cassidy (right) with fieldworkers Reino Maki (left) and Ben Crane in front of a “Word Wagon” in Madison, Wisconsin, 1965. Photo courtesy of University of Wisconsin–Madison Archives.

The scene is a mysterious one, beguiling, thrilling, and, if you didn’t know better, perhaps even a bit menacing. According to the time-enhanced version of the story, it opens on an afternoon in the late fall of 1965, when without warning, a number of identical dark-green vans suddenly appear and sweep out from a parking lot in downtown Madison, Wisconsin. One by one they drive swiftly out onto the city streets. At first they huddle together as a convoy. It takes them only a scant few minutes to reach the outskirts—Madison in the sixties was not very big, a bureaucratic and academic omnium-gatherum of a Midwestern city about half the size of today. There is then a brief halt, some cursory consultation of maps, and the cars begin to part ways.

All of this first group of cars head off to the south. As they part, the riders wave their farewells, whereupon each member of this curious small squadron officially commences his long outbound adventure—toward a clutch of carefully selected small towns, some of them hundreds and even thousands of miles away. These first few cars are bound to cities situated in the more obscure corners of Florida, Oklahoma, and Alabama. Other cars that would follow later then went off to yet more cities and towns scattered evenly across every corner of every mainland state in America. The scene as the cars leave Madison is dreamy and tinted with romance, especially seen at the remove of nearly fifty years. Certainly nothing about it would seem to have anything remotely to do with the thankless drudgery of lexicography.

But it had everything to do with the business, not of illicit love, interstate crime, or the secret movement of monies, but of dictionary making. For the cars, which would become briefly famous, at least in the somewhat fame-starved world of lexicography, were the University of Wisconsin Word Wagons. All were customized 1966 Dodge A100 Sportsman models, purchased en masse with government grant money. Equipped for long-haul journeying, they were powered by the legendarily indestructible Chrysler Slant-Six 170-horsepower engine and appointed with modest domestic fixings that included a camp bed, sink, and stove. Each also had two cumbersome reel-to-reel tape recorders and a large number of tape spools.

The drivers and passengers who manned the wagons were volunteers bent to one overarching task: that of collecting America’s other language. They were being sent to more than a thousand cities, towns, villages, and hamlets to discover and record, before it became too late and everyone started to speak like everybody else, the oral evidence of exactly what words and phrases Americans in those places spoke, heard, and read, out in the boondocks and across the prairies, down in the hollows and up on the ranges, clear across the great beyond and in the not very long ago.

These volunteers were charged with their duties by someone who might at first blush seem utterly unsuitable for the task of examining American speech: a Briton, born in Kingston, of a Canadian father and a Jamaican mother: Frederic Gomes Cassidy, a man whose reputation—he died twelve years ago, aged ninety-two—is now about to be consolidated as one of the greatest lexicographers this country has ever known. Cassidy’s standing—he is now widely regarded as this continent’s answer to James Murray, the first editor of the Oxford English Dictionary; Cassidy was a longtime English professor at the University of Wisconsin, while Murray’s chops were earned at Oxford—rests on one magnificent achievement: his creation of a monumental dictionary of American dialect speech, conceived roughly half a century ago, and over which he presided for most of his professional life.

Stump Speaking, by George Caleb Bingham, c. 1853. Saint Louis Art Museum, Missouri.

The five-thousand-page, five-volume book, known formally as the Dictionary of American Regional English and colloquially just as DARE, is now at last fully complete. The first volume appeared in 1985: it listed tens of thousands of geographically specific dialect words, from tall flowering plants known in the South as “Aaron’s Rod,” to a kind of soup much favored in Wisconsin, made from duck’s blood, known as “czarina.” The next two volumes appeared in the 1990s, the fourth after 2000, so assiduously planned and organized by Cassidy as to be uninterrupted by his passing. The fifth and final volume, the culminating triumph of this extraordinary project, is being published this March—it offers up regionalisms running alphabetically from “slab highway” (as concrete-covered roads are apparently still known in Indiana and Missouri) to “zydeco,” not the music itself, but a kind of raucous and high-energy musical party that is held in a long swathe of villages arcing from Galveston to Baton Rouge.

“Aaron’s rod” to “zydeco”—between these two verbal bookends lies an immense and largely hidden American vocabulary, one that surely, more than perhaps any other aspect of society, reveals the wonderfully chaotic pluribus out of which two centuries of commerce and convention have forged the duller reality of the unum. Which was precisely what Cassidy and his fellow editors sought to do—to capture, before it faded away, the linguistic coat of many colors of this immigrant-made country, and to preserve it in snapshot, in part for strictly academic purposes, in part for the good of history, and in part, maybe, on the off chance that the best of the lexicon might one day be revived.

The idea of creating a dictionary of regional dialect English was born across the Atlantic, in England itself. DARE’s fons et origo was the serial publication, commenced in 1896, of the English Dialect Dictionary. The hero in the story of this six-volume work, now seldom seen but still revered by professional lexicographers, is a little-remembered Yorkshireman named Joseph Wright, a kindly, bearded, country-accented book collector who had fought his way out of utter poverty (his father was a sometime wool weaver and quarryman from a Yorkshire hamlet inappositely named Idle) to become a professor in comparative philology at Oxford.

Wright, who had studied German and mathematics before obtaining a PhD in philology, came to believe that dialect, just like its kissing cousin slang, was a key component of any language as vital as English. To preserve it, to note it, to promote and employ it was a noble project, one that could help keep the mainstream language into which it often percolated flourishing and healthy. It was to this end that he was set when a group called the English Dialect Society handed him—shortly after he had joined Oxford’s philology department—roughly a million yellowing paper slips, weighing in all nearly a ton. Each bore a dialect word or phrase that had been painstakingly gathered, from Cornwall to the Shetlands, by members of the tiny army of bespectacled and corduroyed enthusiasts who made up the Society.

Professor Wright, his mind unboggled by the scale, swiftly resolved that he would likely need to accumulate a million more slips to forge the dictionary he had in mind. But there was a problem: even in those more enlightened Victorian times, when projects of monumental scale—like the OED and the Dictionary of National Biography—were begun without regard for cost, no British publisher would agree to take this particular project on. So Wright decided to assume responsibility for financing it himself. For the next fourteen years he slaved singlemindedly with a team of assistants in a room provided by Clarendon, Oxford’s press (no doubt with, in Oxford dialect, his oak sported—his door shut firm).

He illustrated the hundred thousand headwords that he ultimately cobbled together from the slips and elsewhere in printed books—dialect words from the various regions of England, from Scotland and Ireland, and even some American words that had made their way, ship-borne, all the way back to Britain (such as “to snub,” an American-made reworking of the melancholy verb “to sob”)—with no fewer than half a million quotations, filling five thousand printed pages in doing so. It was a signal triumph of lexical dedication. And to cap it all: on the day that his first volume was finally published, Wright formally proposed marriage to a former student of his who had in later years become the project’s chief secretary. Small wonder, with such achievements to his name, that he and Mrs. Wright were widely declared the happiest couple in all of Oxford.

The idea of making a fully formed dictionary of America’s various dialect words came soon after the EDD was finished in 1905. The American Dialect Society had been formed in 1889, and just as in Britain, its enthusiasts had been wandering, chatting, listening, reading—and capturing unfamiliar words and pinning them, spatchcocked and anatomized, onto index cards. From time to time there were lists published in the ADS journal, Dialect Notes, but depressions and wars and the multiplicity of distractions to which even students of the lexicon are prey meant there was a somewhat haphazard, catch-as-catch-can approach to collecting the vast panoply of dialect words with which time, geography, and a whole-world immigrant population had so amply gifted America.

This clearly wasn’t good enough for the unrestrained ambition of Fred Cassidy. After studying at Oberlin and the University of Michigan he had settled in Wisconsin, playing the spider at the middle of the country’s linguistic web. He had already displayed a fascination with American regionalisms, publishing in 1947 a slim book on the place names around Madison (where there were towns with names like Mazomanie, Blue Mounds, and Black Earth). A questionnaire he had sent out in 1948 to thousands by mail from Madison, asking about slang usage in the rural communities of Wisconsin, was being seen as a model of its kind, a signal success. And by the late sixties, he was well on the way to making a name for himself: consolidating his advancing reputation, his Dictionary of Jamaican English (with the etymologies of rather daring new words like “ganja” and “dreadlocks,” and some thousands of others besides) would be winning glowing reviews on its publication in 1967.

In 1962, however, Cassidy had begun to badger the ADS. Could they not, he asked (and then kept on asking), initiate a great dictionary project too, a project that would do for America what the EDS had done for Britain? It took a while for his pleas to be answered, but in 1963 the ADS leadership agreed. And then, in pondering how best to go about creating such a massive masterwork, the Society came swiftly to confirm what Cassidy already suspected: that he, Cassidy, was the best possible candidate to spearhead the effort. He had sufficient wood, as the Jamaicans like to say, to create the very dictionary which America so badly needed. However, it was far from an easy project to begin. Aside from the lists published in the various pamphlets and journals of the ADS, there was precious little material to use as fire starter. Cassidy had no two-thousand-pound benison of yellowed word-slips bestowed upon him. Most of the data for his great dictionary would have to be assembled anew. But just like James Murray, who famously worked under the OED’s guiding principle that to collect all English words, all English writing had to be read, Cassidy decided to think big. To collect all American regional speech, all American language had to be listened to and recorded, and all American regions had to be visited. Such a monumental work would take time, people—and money.

But Cassidy was not a man to be daunted by such trivial problems. Together with a colleague, one of his students named Audrey Duckert, he wrote a brand-new questionnaire for use out in the field; he received a grant from the U.S. Office of Education to pay for a fleet of vans—the famous Word Wagons—that he deemed were necessary for visiting the farther-flung corners of the Republic; he worked out a battle plan and timetable for this immense gathering-in; and he calculated a system of subsistence payments for a team of some eighty volunteers, graduate students and a few professors, missionaries who shared his zeal for what he saw as a truly holy calling.

In the fall of 1965 he then formally set these teams to work, a-hunting and a-gathering, initially by waving them out of the parking lot in downtown Madison, and from there onto the streets and back roads of the country. What the teams would bring back over the following five years is a quite extraordinary record—a record that lays out the amazing wealth of a hitherto almost unknown American language.

Three improbably large numbers are critical to any appreciation of the linguistic component of the study, and what it eventually accomplished: 1,002, 2,777, and 1,847. The Madison volunteers fanned out to 1,002 carefully chosen communities (selected for being generally stable, old, and variegated) across the country. There they interviewed, and at length, 2,777 people—most of them middle-aged or older, assumed thereby to have a greater familiarity with the lexical history of their communities, and the greater proportion of them (chosen for the same reason) long-term residents. And—though one may gasp at the impertinence, the cheek, the brass neck, and the chutzpah of it all—the eighty youngsters who made the study presented each of these 2,777 old-timers in the 1,002 chosen communities with a list of no fewer than 1,847 questions. Three hundred twenty-five pages worth of interrogation—no census taker or pollster or focus-group leader of today could hardly hold a candle to the soldiers in Fred Cassidy’s dictionary army.

With 1,847 questions, each interview would take as much as a week to complete—a testament, perhaps, to the lazier tempo of the times, or else to the pertinacity of those whom Fred Cassidy selected to do his lexicographic heavy lifting. Nearly a century before, James Murray asked interested volunteer readers around the world to assist in the creation of the OED by jotting down what they read, maybe one quote at a time. Seventeen years later, Joseph Wright had as many as six hundred volunteers occasionally noting words and expressions they heard in their communities. Fred Cassidy, on the other hand, a taskmaster extraordinaire, had all of his volunteers go out and ask questions, on tape, day after day after day, and then transcribe the answers. In addition to respondents’ answers, the volunteers also recorded most of them reading a famous all-the-phonemes-there-are test story called “Arthur the Rat,” the results of which have been used for the past half century for the study of variations in regional accents. The fieldwork was Herculean.

Herculean, that is, in the performance of the lexical work alone One shouldn’t forget the nonlexical difficulties the fieldworkers might have encountered too. This being the late sixties, the time of Bobby Kennedy, Martin Luther King, My Lai, and the Watts riots, suspicion, hostility, and violence abounded—and not a few of the volunteers, especially the shaggier-haired and more obviously intrusive and inquisitive, were chased out of town, threatened, and even arrested, accused of stirring things up and fomenting trouble.

When seen in full, Cassidy’s 325-page book of questions does not merely inspire awe. It also has a kind of poetry about it, the interrogations evidently made to blend lexical efficiency with literary elegance. They run from simple temporal inquiries, like Question A1—What do you call the time in the early morning before the sun comes into sight? to the fill-in-the-blank Question 0047b, a query that relates, improbably, to the sweating of horses: They wouldn’t have caught cold if they hadn’t_____(so much.) In between are all manner of word-inquiries. Most are slyly innocent, others are more blatantly invasive.

What joking names do you have for an alarm clock? For a toothpick? For a container for kitchen scraps? Or an indoor toilet? Or women’s underwear? When a woman divides her hair into three strands and twists them together, you say she is_____her hair? What words do you have to describe people’s legs if they’re noticeably bent, or uneven, or not right? What do you call the mark on the skin where somebody has sucked it hard and brought blood to the surface?

There are questions about the words used locally to describe loitering, getting splinters, sleeping late, staring open-mouthed, beating someone up. Fred Cassidy and his team wanted to know all about health and sickness, children’s games, religion, smoking and liquor, entertainment, emotional states, friendship, school-going, exclamations (What do you shout in these parts to drive away a dog, a child, a fly?), different ways of saying “uptown” and “downtown,” the names of the sounds that gas makes within a hungry person’s stomach, and for the ruder noises made when it emerges from either end of the alimentary canal.

The inquiry seemed to cover every imaginable topic—love and marriage, loose bowels, gossips, students, fruit, industrial plants, insects, flowers, scolds—except that there appears to be, in those more academically prudish times, no sex whatsoever. The names that were discovered around the nation for the giving of a vigorous kiss are to be found, for sure; and the various names for a marriage hurriedly arranged because a child is on the way, are listed by region also. But as to what are the various names for the act that brought the child into being in the first place—of that Fred Cassidy’s questionnaire, and so his eventual dictionary, are memorably silent.

The Word Wagons went everywhere—from Blaine to Key West, Eastport to San Diego, and to inhabited Alaska, even. Those who undertook the odysseys interviewed all manner of what would be called “informants”—the first on the immense eventual list (each identified only by code) being a sixty-one-year-old black maid in Jasper, Alabama, the 2,777th a seventy-one-year old white “farm woman” in Cottage Grove, Wisconsin. All apparently sat patiently and tolerantly through the rigors of their questioning. And though their names may be long kept secret, their names of their hometowns, when cached together, make the purest poetry too: Tangier, Virginia; Honey Brook, Pennsylvania; Vevay, Indiana; Snowflake, Arizona: who could not but exult in this vast tapestry of difference, seen even in the town names alone?

It took five years to compile the information and send it all back to Madison—the completed forms, the annotated and transcribed tapes, the spiral-backed field notebooks, the punch cards into which the geographical, statistical, and frequency data were all siphoned using the University’s room-sized UNIVAC computer. And then Cassidy and his staff of lexicographers—including the current chief editor, Joan Hall, who has lived with the project for most of her professional life—took over and got down to their allotted tasks

The work of these deskbound editors now became more Sisyphean than Herculean. They started with letter “A” (a point worth making, since the OED’s Third Edition was actually started at the letter “M”). “On to Z” soon became their watchword (and was reportedly even engraved on Fred Cassidy’s tombstone). These clever and dedicated worker-bees patiently drew on all the computer data, they read and parsed the notebooks, they consulted immense libraries of patois and vernacular and consulted scores of earlier dialect dictionaries, and they then patiently and with scrupulous attention to detail listed in alphabetical order, with headings for etymology, orthography, pronunciation, and regional frequency, and with illustrative quotations arranged by date, all of the discovered dialect lexemes, lemmae, and phrases—recording in print such delights as “blueweed,” “williwag,” “Adam’s housecat,” “podunk,” “dropped egg,” “baby carriage,” “beau dollar,” “blind pig.” Any word offered with certainty by the informants—no matter how arcane it might have seemed—went in to the published vocabulary: “angledog,” “bungalow apron,” “brodie,” “chagalag,” all America’s topographically distinct and regionally generated words were duly recorded, listed, and entered.

An Appeal for Mercy, by Marcus Stone, 1876.

They also drew clever maps, adjusted for population (Massachusetts thus being larger than Idaho, New York almost the same size as California) and on them plotted the geographical frequency of the more interesting discoveries—showing at a glance that it was people in the Appalachians who most commonly called an abscess a “bealing,” for instance, and how a bird, a particularly pretty kind of swift, was known as a “chimney sweep” more commonly in the Deep South than elsewhere.

And so they gathered and annotated all of these, and in total some sixty thousand further lexical illustrations of just how varied and mismatched and chaotic this country truly is—or was, at least, half a century ago. There is in truth little new, or newly found, in the dictionary: this is a deliberately fashioned portrait of the regional language of America as it was half a century ago—one small criticism that can fairly be leveled at a dictionary of the words of a vanished world, that is now published for a modern world so much more accustomed to the immediate and the up to date.

The completed dictionary memorializes an American language that is demarcated by geography, topography, heritage, immigration. In that sense it differs significantly from the many slang dictionaries, which display a quite different, but equally informal language, that is denominated largely by craft, by age, by persuasion. The language of thieves and computer geeks, of carnival workers and sportsmen, of drug addicts and prostitutes and the homosexual world is qualitatively different from the dialect words of those who have lived for years in the valleys of West Virginia, say, or the plains of South Dakota. These two kinds of languages may occasionally overlap, but they are by no means cut from the same cloth.

It is customary to suppose that it is the constant addition of slang to the mainstream of standard English that keeps American English so deliciously alive as a language—rendering it the most robust, flexible, and influential of all languages known. The recent publication of two immense new slang lexicons—Jonathan Lighter’s half-completed Historical Dictionary of American Slang, and Jonathon Green’s Dictionary of Slang—reinforces this notion, reminding us of its truth. Browsing through the thousands of pages of the slang dictionaries displays vividly—and in a way that browsing through DARE does not—just how much the informal cutting-edge vocabulary adds, in great measure, to the richness of what we speak and write today.

Not all slang words make it into the formal vocabulary, of course—even after a century’s slang usage, no New York Times reporter would write that “the cops” were investigating a crime. But he would write, and without fear of an editor’s objection, that police were looking into charges that someone had “filched” a purse, and that he later had stashed the “booty” in his room—in so writing employing two words that were once egregiously informal slang, and yet are now made entirely acceptable to all.

Most slang is temporary, and vanishes utterly. Some large proportion remains employed as slang alone. But a sufficient percentage still makes its way, year upon year, into the commonly written and read versions of English—a happenstance that makes its study and recording exciting and valuable, a vital component of the joy of English. By contrast the five volumes of DARE seem more like tombstones, works of great scholarship and high purpose, but at the same time a record of a language that is slowly being preserved in amber, while dying out from under-use and fading away, as with all the “withals” and “prithees” and “zounds” and “odds bodkins” of former times. This does not render the five great books as being without purpose—they are read avidly by actors and acting coaches in Hollywood when making movies set in the Ozarks or ancient Idaho; lawyers swear by it, as dreadful crimes have been solved by the forensic study of ransom notes, DARE to hand; and literate cooks like to trace the origins of dishes from the names of spices and plant types recorded in these columns. But all of such study and use is related to the English of yesterday—little of it is relevant to the use of English today, and most certainly none of it has any significant resonance in the language that we are ever likely to employ tomorrow.

Not too far away from Madison, down in Hyde Park, Illinois, there have been recent celebrations for the completion of another, similarly monumental project of lexicography. The University of Chicago’s Assyrian Dictionary was begun in 1921, and was completed ninety years later. It records in fine detail just how those in Mesopotamia wrote and read on clay tablets four thousand years ago. The completion of the work in the winter of 2011 was greeted with much academic joy, and with the exchanging of accolades and laurel wreaths.

And as with the Assyrian volumes so, one might say not entirely unfairly, with Fred Cassidy’s Dictionary of American Regional English. A monument, a memorial, a piece of work both magisterial and majestic that someone, somewhere, was one day bound to undertake. So to all who take pleasure from the complex mechanics of human communication: let us rejoice that someone did indeed undertake this gigantic task, and recorded so fascinating a morsel of American linguistic history—and that they did so happily, without anyone having the temerity to ask or to wonder at the reason why.