Making a film means, first of all, to tell a story. That story can be an improbable one, but it should never be banal. It must be dramatic and human. What is drama, after all, but life with the dull bits cut out?

—Alfred Hitchcock, 1962Word for Word

Peter Mark Roget’s Thesaurus was the creation of an obsessive list-maker that became a tool and a temptation for generations of writers.

By Ben Zimmer

The Writing Master, by Thomas Eakins, 1882. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, John Stewart Kennedy Fund.

I can see my own copy up on a high shelf.

I rarely open it, because I know there is no

such thing as a synonym and because I get nervous

around people who always assemble with their own kind,

forming clubs and nailing signs to closed front doors

while others huddle alone in dark streets.

I would rather see words out on their own, away

from their families and the warehouse of Roget,

wandering the world where they sometimes fall

in love with a completely different word.

Surely, you have seen pairs of them standing forever

next to each other on the same line inside a poem,

a small chapel where weddings like these,

between perfect strangers, can take place.—Billy Collins, “Thesaurus”

It has become something of a literary cliché to bash the thesaurus, or at the very least, to warn fellow writers that it is a book best left alone. Some admonitions might be blunt, others wistful, as with Billy Collins musing on his rarely opened thesaurus. But beyond the romantic anthropomorphizing of words needing to break free from “the warehouse of Roget,” what of Collins’ more pointed criticism, that “there is no/such thing as a synonym”? That would suggest that the whole enterprise of constructing a thesaurus is predicated on a fiction.

It is only a fiction if one holds fast to the notion that synonyms must be exactly equivalent in their meaning, usage, and connotation. Of course, under this strict view, there will never be any “perfect” synonyms. No word does exactly the job of another. In the words of the linguist Roy Harris, “If we believe there are instances where two expressions cannot be differentiated in respect of meaning, we must be deceiving ourselves.”

But the synonyms that we find gathered together in a thesaurus are typically more like siblings that share a striking resemblance. “Brotherly” and “fraternal,” for instance. Or “sisterly” and “sororal.” They may correspond well enough in meaning, but that should not imply that one can always be substituted for another. Consulting a thesaurus to find these closely related sets of words is only the first step for a writer looking for le mot juste: the peculiar individuality of each would-be synonym must then be carefully judged. Mark Twain knew the perils of relying on the family resemblance of words: “Use the right word,” he wrote, “not its second cousin.”

No matter how tempting the metaphor, though, words are not people. We cannot run genetic tests on them to determine their degrees of kinship, and a thesaurus is not a pedigree chart. We can, nonetheless, look to it as a guidebook to help us travel around the semantic space of our shared lexicon, grasping both the similarities that bond words together and the nuances that differentiate them.

This was, in fact, more or less the mission of Peter Mark Roget when he published the first edition of his Thesaurus of English Words and Phrases in the spring of 1852. He organized sets of synonyms according to one thousand categories, neatly arrayed in a two-column format. Roget was utterly obsessive about making lists, keeping a notebook full of them as early as eight years old, and by age twenty-six he had compiled a hundred-page draft of what would become his greatest work. List making was a welcome relief from his chronic depression and tumultuous family life; it was a way of imposing order on a messy reality. In his autobiography, he would not bring himself to explore his personal troubles; instead he dispassionately noted places he visited, moving days, birthdays, and death days. He called it “List of Principal Events.”

In his biography of Roget, The Man Who Made Lists, Joshua Kendall argues that Roget created a “paracosm,” or alternate universe, in the orderly lists of words he began making in childhood: “both a replica of the real world as well as a private, imaginary world.” The thesaurus that would grow out of the lists was even more hyperorderly. The unruliness of language—and the world of concepts that words denote—could be tamed in his pages. When he discovered that he actually had 1,002 concepts listed instead of his planned 1,000, he simply condensed two entries to achieve his round number: “Absence of Intellect” became 450a and “Indiscrimination,” 465a.

Roget’s thesaurus was crucially a conceptual undertaking, and, according to Roget’s deeply held religious beliefs, a tribute to God’s work. His efforts to create order out of linguistic chaos harks back to the story of Adam in the Garden of Eden, who was charged with naming all that was around him, thereby creating a perfectly transparent language. It was, according to the theology of Saint Augustine, a language that would lose its perfection with the Fall of Man, and then irreparably shatter following construction of the Tower of Babel. By Roget’s time, Enlightenment ideals had taken hold, suggesting that scientific pursuits and rational inquiry could discover antidotes to Babel, if not a return to the perfect language of Adam. Though we no longer cling so tightly to these Enlightenment notions about language in our postmodern age, we still carry with us Roget’s legacy, the view that language can somehow be wrangled and rationalized by fitting the lexicon into tidy conceptual categories.

Roget intended for his readers to immerse themselves in the orderly classification system of the thesaurus so that they might better understand the full possibilities for human expression. As Roget first conceived it, the book did not even have an alphabetical index—he included it later as an afterthought. His goal, then, was not to provide a simple method of replacing synonym A with synonym B but instead to encourage a fuller understanding of the world of ideas and the language representing it.

In England, the Thesaurus was widely praised upon publication. The Westminster Review lauded the work’s “ideal classification,” which meant that “the whole Thesaurus may be read through, and not prove dry reading either.” An international edition would eventually popularize his work in the United States as well, becoming a household item in the 1920s during the crossword craze. Eventually “Roget” would become synonymous with the thesaurus itself, even if many of the contemporary reference works that bear his name share little resemblance to his careful classification system.

More than a century and a half later, the impact of Roget’s creation continues to reverberate in the proliferation of thesauruses, both in print and electronic varieties. Yet the thesaurus has also come under fire time and time again—what does it have to offer the modern writer?

Qualms about the proper use of the thesaurus go back to Roget’s original. An anonymous review in the September 1852 issue of The Athenaeum voiced the concern that the thesaurus would simply be used as a “crutch” for writers, who would be better off avoiding “the frequent recurrence to a work of this kind.” The view of it as a mere crutch persists to this day, especially among writers of fiction and poetry who see the frequent consultation of it as somehow impeding natural expression. Consider this pronouncement from Stephen King in a 1986 piece for The Writer:

You want to write a story? Fine. Put away your dictionary, your encyclopedias, your World Almanac, and your thesaurus. Better yet, throw your thesaurus into the wastebasket. The only things creepier than a thesaurus are those little paperbacks college students too lazy to read the assigned novels buy around exam time. Any word you have to hunt for in a thesaurus is the wrong word. There are no exceptions to this rule.

The poet Mark Doty was similarly forthright in a 2011 interview:

If you write a poem with the aid of a thesaurus, you will almost inevitably look like a person wearing clothing chosen by someone else. I am not sure that a poet should even own one of the damn things.

Some writers counsel that a thesaurus should, at the very least, be kept at arm’s length, like Billy Collins’ “copy up on a high shelf.” When the Guardian asked Irish novelist Roddy Doyle for his rules for aspiring writers, one of them was as follows:

Do keep a thesaurus, but in the shed at the back of the garden or behind the fridge, somewhere that demands travel or effort. Chances are the words that come into your head will do fine.

Margaret Atwood, on the other hand, supplied her own cardinal rule of writing to the Guardian: “You most likely need a thesaurus, a rudimentary grammar book, and a grip on reality.”

A young Sylvia Plath was more enthusiastic, calling her thesaurus the book that she “would rather live with on a desert isle than a Bible.” She relied on her copy of Roget heavily when composing the poems in her first collection, The Colossus, though she apparently outgrew her thesaurus dependence by the time she wrote her famous Ariel poems. Dylan Thomas, Plath’s contemporary, leaned heavily on a thesaurus when writing his later poetry, as researchers have discovered by analyzing his manuscripts. For Thomas, his thesaurus likely did serve as a crutch of sorts, since he was in the grips of alcoholism and his writing was deteriorating. We can think of Thomas’ case as an object lesson in approaching all things in moderation, be it the bottle or the thesaurus.

To be sure, the potential for abuse is a constant danger, especially for eager students who may go overboard when hunting for impressive words. When I speak to student groups about the use and misuse of the thesaurus, I like to open with a cautionary tale. The story, I explain, is told in the memoir of a prominent American politician, recounting his experience as a new student at a prestigious Eastern boarding school:

I remember the first paper I wrote. I thought I was in over my head, so I consulted the Roget’s Thesaurus Mother had given me, searching for some big, impressive words. I wanted to show off for my Eastern professors. It was a story about emotions, and I was trying to find a unique way to describe “tears” running down my face. My discussion of “lacerates” falling from my eyes did catch the teacher’s attention, but not in the way I had hoped. The paper came back with a “zero” marked so emphatically that it left an impression visible all the way through to the back of the blue book. So much for trying to sound smart.

My student audience can usually guess pretty quickly that the memoirist in question is George W. Bush. The former president uses the anecdote in A Charge to Keep to illustrate his fish-out-of-water status attending the Phillips Academy prep school at Andover, and also to own up to his much-derided linguistic shortcomings. In a 2000 profile of Bush in Vanity Fair, Gail Sheehy even used the episode as circumstantial evidence that he was dyslexic, quoting an expert as saying that his confusion over word choice suggested that “he really didn’t understand the language.” The simpler explanation is that he didn’t understand how to use the thesaurus his mother gave him, and thus got tripped up by the homography of “tears.”

Every teacher of composition probably has a few horror stories along these lines. Unlike Bush with his print thesaurus, students these days would more likely consult one online or directly built into their computer’s operating system. The simplicity of using an electronic thesaurus is a double-edged sword, tempting students into quick substitutions without thinking carefully about nuances of word usage. In a critique of thesauruses (and Roget in particular) published in The Atlantic in 2001, Simon Winchester gave the example of a student who “attempted to improve the phrase ‘his earthly fingers’ by changing it to ‘his chthonic digits.’” Elsewhere he calls the thesaurus “a calculator for the lexically lazy: used too often, relied on at all, it will cause the most valuable part of the brain to atrophy, the core of human expression to wither.”

Winchester is quite right to be concerned about the ease of search-and-replace synonymy in the age of the word processor. Unthinking substitutions along the lines of the young Mr. Bush’s “lacerates” can now be multiplied many times over, with lightning speed. Fans of the television show Friends may recall the episode in which the dim-witted Joey Tribbiani discovers the built-in thesaurus in his word-processing program and tries to spruce up a letter of recommendation for his friends’ adoption agency. He thesaurusizes every word, so that the sentence “They are warm, nice people with big hearts” turns into “They are humid, prepossessing homo sapiens with full-sized aortic pumps.”

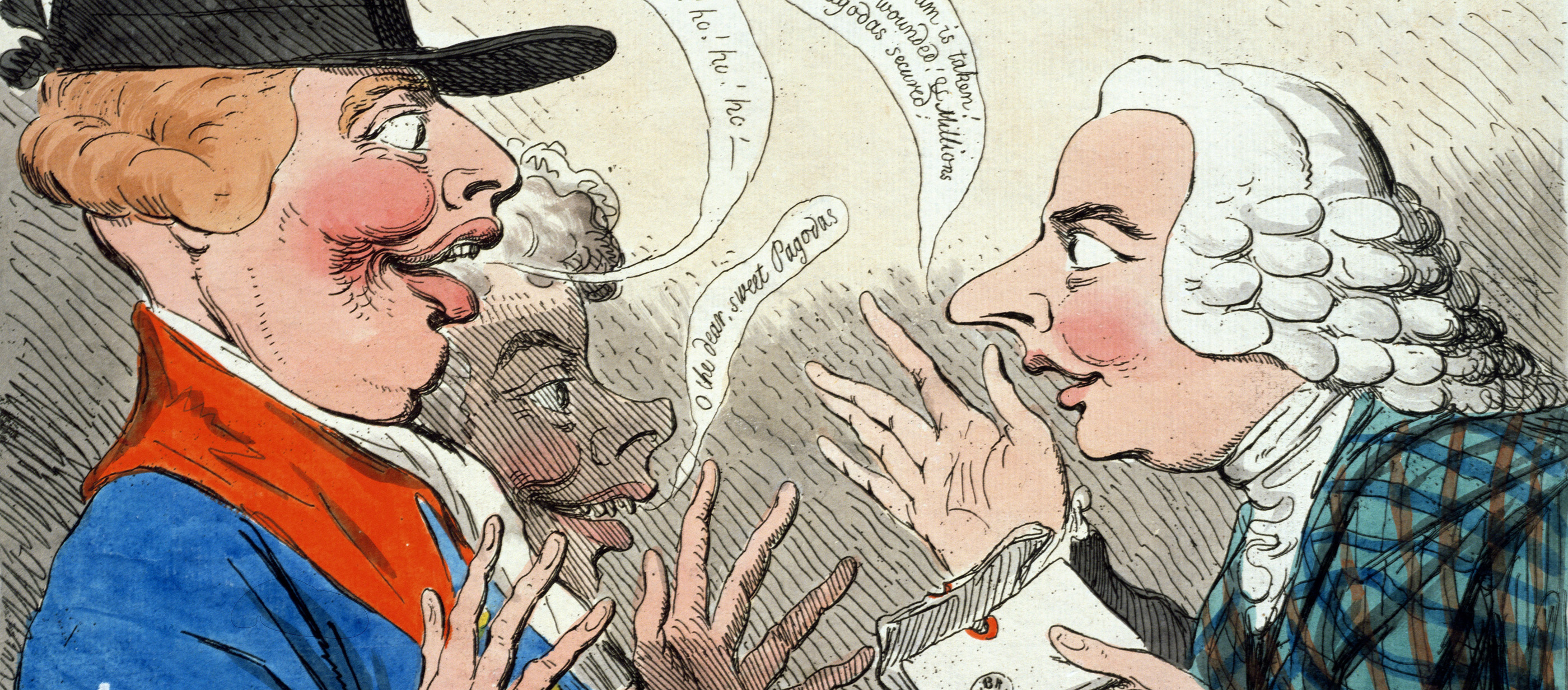

Scotch Harry’s News, or, Nincumpoop in High Glee, by James Gillray, 1792. © The Warden and Scholars of New College, Oxford, The Bridgeman Art Library International.

That bit of sitcom silliness has actually turned into a grim reality, now that online content farms use so-called spinning software to modify a source text by automatically swapping out words with ostensible synonyms. (The goal is to create new textual fodder that can be used on websites without search engines like Google suspecting that the content has been duplicated from elsewhere.) I recently came across a particularly ham-handed example on a news aggregator which lifted an article from the Star-Ledger about a looming fight between two congressional candidates. The original said that “the Democratic showdown…will be bloody and fairly evenly matched considering the county machinery behind each candidate.” In the “spun” version, the showdown “will be full of blood and sincerely uniformly suited deliberation the county equipment at the back any candidate.” Sadly, this sort of thesaurus-driven gobbledygook can be found in abundance online, as if Joey and his full-sized aortic pump had taken over the Internet.

If automatic search and replace represents the dark side of synonymy in the digital age, there are plenty of causes for optimism in more sophisticated approaches to contemporary thesaurus making. A thesaurus, like any reference tool, requires active participation from its readers to unlock its potential utility. But one that is well-designed, whether print or digital, also makes that participation enjoyable and enlightening, encouraging the user to do more than take in a quick drive-by of synonyms. In compiling the first English thesaurus, Roget’s hope was that his readers would immerse themselves in a realm of concepts and their linguistic associations. One hundred and sixty years later, there are many novel ways that a thesaurus can provide that kind of immersion in the world of words.

Twenty-first-century reference works seem to be moving inexorably toward an online-only existence, but for the time being we can appreciate the distinct pleasures of both print and electronic creations. The print thesaurus affords a more leisurely stroll through its pages, with possibilities ripe for serendipitous discovery. The electronic versions, on the other hand, may appeal to our “give me a word now” impulse for instant gratification. But they can also stimulate the exploration of language by means of free-flowing user interfaces, with hyperlinks or other navigational tools carrying the user from word to word and from meaning to meaning.

Online thesauruses can go even further in bringing the interconnectedness of the English lexicon to life on the screen. The Visual Thesaurus (for which I serve as executive producer) creates interactive displays of the relationships between words and between senses of words. Moving through this type of semantic visualization, the jumps can be unexpected, allowing for the emergence of a different kind of serendipity than the kind that a print reference normally provides. The entire inventory of senses for a given word, with accompanying synonyms for each sense, can blossom forth like a flower on the screen. Such a visual efflorescence inspired George L. Dillon, a professor of English at the University of Washington, to write, “If indeed it is the case that we access all of the senses of words for a very brief interval when processing natural language, what wonderful things must be swimming about in our minds!”

Another significant effort in contemporary thesaurus-making admirably straddles the print/digital divide. The Historical Thesaurus of the Oxford English Dictionary was conceived in 1965 at the University of Glasgow as a project that would index all the words in the OED, organizing them by their meanings and by their first known date of use. In 2009, at long last, HTOED was published in two massive volumes, the first providing a chronological listing of words in different conceptual classes and the second providing an index to find particular meanings of words in the book’s elaborate Roget-style hierarchy, from the abstract to the specific. While it is easy to get lost in its pages, HTOED clearly needed an online home to maximize its practicality for both casual and scholarly readers. Thus it was incorporated into the online OED in 2010, and there it truly thrives. Because the categories of words are presented chronologically, one can quickly see, for instance, how 149 terms for a “contemptible person” extend from “worm” and “wretch” in Old English to late-twentieth-century slang offerings like “scuzzbag” and “sleazeball.” For a writer, searching for just the right word can turn into an adventure in historical verisimilitude. A novelist or playwright seeking epithets for dialog set in the early seventeenth century can zero in on such terms as “viliaco” (1600), “snotty-nose” (1604), “sprat” (1605), “wormling” (1605), and “shag-rag” (1611).

What, then, should we expect a thesaurus to do for us? Simply allow us to replace one word with a near equivalent in a mechanical fashion? Such arid utilitarianism does little justice to the various ways that a thesaurus can shed light on language and encourage lexical explorations. A thesaurus, as we have seen, can mine rich usage data from textual corpora to paint a picture of how words are used in actual context. It can create new spatial metaphors for semantic connections. Or it can add a historical dimension to trace how words related to a given concept have ebbed and flowed over the centuries. These are but some of the directions that the twenty-first-century thesaurus is headed in, directions unforeseen by Roget in his time. Though we can be sure that he would have deplored the mindlessness of the word processor’s search-and-replace shortcuts, I feel equally confident that Roget would have appreciated the ways that new technologies can deepen our appreciation of the lexicon’s richness in all of its interwoven splendor.