Two crimes undid me: a poem and a mistake.

—Ovid, 10Deliverance

It is not from death I request thee to deliver me, but from this terror of torment’s eternity.

“It is not from death I request thee to deliver me, but from this terror of torment’s eternity. Thy brother’s body I only pierced unadvisedly; his soul meant I no harm to at all. My body and soul both shalt thou cast away quite if thou dost at this moment what thou mayest. Spare me, spare me I beseech thee; by thy own soul’s salvation I desire thee—seek not my soul’s utter perdition. In destroying me, thou destroyest thyself and me.”

Eagerly I replied, “Though I know God will never have mercy on me except I have mercy on thee, yet of thee no mercy would I have. Revenge in our tragedies is continually raised from hell—of hell do I esteem better than heaven, if it afford me revenge. There is no heaven but revenge. I tell thee, I would not have undertook so much toil to gain heaven, as I have done in pursuing thee for revenge. Divine revenge, of which (as of the joys above) there is no fullness or satiety. Look how my feet are blistered with following thee from place to place. I have riven my throat with overstraining it to curse thee. I have ground my teeth to powder with grating and grinding them together for anger when any hath named thee. My tongue with vain threats is blown and waxen too big for my mouth; my eyes have broken their strings with staring and looking ghastly as I stood devising how to frame or set my countenance when I met thee. I have near spent my strength in imaginary acting on stone walls what I determined to execute on thee. Entreat not, a miracle may not reprieve thee, villain—thus march I with my blade into thy bowels.

“Stay, stay,” exclaimed Esdras, “and hear me but one word further. Though neither for God nor man thou carest, but placest thy whole felicity in murder, yet of thy felicity learn how to make a greater felicity. Respite me a little from thy sword’s point and set me about some execrable enterprise that may subvert the whole state of Christendom and make all men’s ears tingle that hear of it. Command me to cut all my kindred’s throats, to burn men, women, and children in their beds in millions by firing their Cities at midnight. Be it Pope, Emperor, or Turk that displeaseth thee, he shall not breathe on the earth. For thy sake will I swear and forswear, renounce my baptism and all interest I have in any other sacrament. Only let me live, how miserable soever—be it in a dungeon amongst toads, serpents, and adders, or set up to the neck in dung. No pains I will refuse, however prolonged, to have a little respite to purify my spirit. Oh, hear me, hear me, and thou canst not be hardened against me.”

At this his importunity, I paused a little, not as retiring from my wreakful resolution but going back to gather more forces of vengeance. With myself I devised how to plague him double in his base mind. My thoughts traveled in quest of some notable new Italianism, whose murderous platform might not only extend on his body, but his soul also. The groundwork of it was this: that whereas he had promised for my sake to swear and forswear and commit Julian-like violence on the highest seals of religion, if he would but this far satisfy me, he should be dismissed from my fury. First and foremost he should renounce God and His laws, and utterly disclaim the whole title or interest he had in any covenant of salvation. Next he should curse Him to His face, as Job was willed by his wife, and write an absolute firm obligation of his soul to the devil, without condition or exception. Thirdly and lastly (having done this), he should pray to God fervently never to have mercy upon him, or pardon him.

Scarce had I propounded these articles unto him, but he was beginning his blasphemous abjurations. I wonder the earth opened not and swallowed us both hearing the bold terms he blasted forth in contempt of Christianity. Heaven hath thundered when half less contumelies against it hath been uttered. Able they were to raise saints and martyrs from their graves and pluck Christ himself from the right hand of his father. My joints trembled and quaked with attending them; my hair stood upright and my heart was turned wholly to fire. So affectionately and zealously did he give himself over to infidelity, as if Satan had gotten the upper hand of our High Maker. The vein in his left hand that is derived from the heart with no faint blow he pierced—and with the full blood that flowed from it writ a full obligation of his soul to the devil. Yea, he more earnestly prayed unto God never to forgive his soul than many Christians do to save their souls.

These fearful ceremonies brought to an end, I bade him open his mouth and gape wide. He did so—as what will not slaves do for fear? Therewith made I no more ado but shot him full into the throat with my pistol. No more spake he after—so did I shoot him that he might never speak after or repent him. His body being dead looked as black as a toad; the devil presently branded it for his own.

This is the fault that hath called me hither; no true Italian but will honour me for it. Revenge is the glory of arms and the highest performance of valour; revenge is whatsoever we call law or justice. The further we wade in revenge, the nearer come we to the throne of the Almighty. To His scepter it is properly ascribed; His scepter He lends unto man when He lets one man scourge another. All true Italians imitate me in revenging constantly and dying valiantly. Hangman to thy task, for I am ready for the utmost of thy rigor.

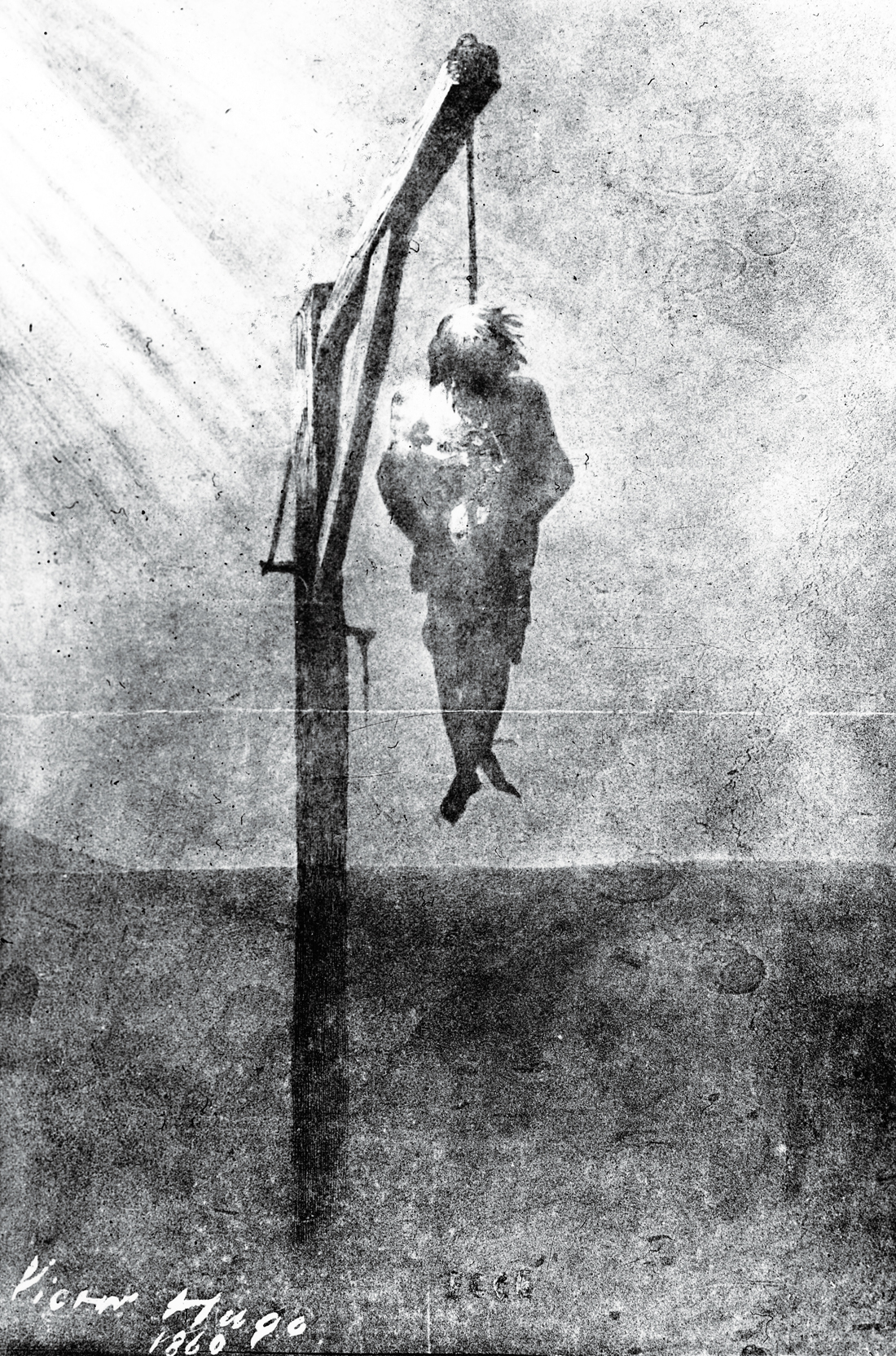

The Hanged Man or John Brown, by Victor Hugo, 1860.

Here withal the people (outrageously incensed) with one conjoined outcry yelled mainly, “Away with him, away with him. Executioner, torture him—tear him, or we will tear thee in pieces if thou spare him.”

The executioner needed no exhortation hereunto, for of his own nature was he hackster good enough: old excellent he was at a bone ache. At the first chop with his wood knife would he fish for a man’s heart and fetch it out as easily as a plum from the bottom of a porridge pot. He would crack necks as fast as a cook cracks eggs—a fiddler cannot turn his pin so soon as he would turn a man off the ladder. Bravely did he drum on this Cutwolf’s bones, not breaking them outright, but like a saddler knocking in of tacks jarring on them quaveringly with his hammer a great while together. No joint about him, but with a hatchet he had for the nonce, he disjointed half and then with boiling lead soldered up the wounds from bleeding. His tongue he pulled out lest he should blaspheme in his torment. Venomous stinging worms he thrust into his ears to keep his head ravingly occupied. With cankers scruzed to pieces he rubbed his mouth and his gums—no limb of his but was lingeringly splintered in shivers.

In this horror left they him on the wheel as in hell, where yet living he might behold in the book of our destinies one murder begetteth another—was never yet bloodshed barren from the beginning of the world to this day.

Thomas Nashe

From The Unfortunate Traveller. Born in 1567, Nashe attended Cambridge University’s St. John’s College. Upon graduating, he joined a circle of writers known as the “University Wits,” a group of playwrights and rabble-rousers that included Christopher Marlowe. In 1597 together with Ben Jonson, he wrote the satirical play The Isle of Dogs that led them both to be prosecuted; Nashe promptly fled London for Yarmouth, where he died in 1601.