The criminal is the creative artist; the detective only the critic.

—G.K. Chesterton, 1911Withholding Redemption

Sinners in the hands of Nathaniel Hawthorne.

In her late, singular interview with Mr. Dimmesdale, Hester Prynne was shocked at the condition to which she found the clergyman reduced. His nerve seemed absolutely destroyed. His moral force was abased into more than childish weakness. It groveled helpless on the ground, even while his intellectual faculties retained their pristine strength, or had perhaps acquired a morbid energy which disease only could have given them.

With her knowledge of a train of circumstances hidden from all others, she could readily infer that, besides the legitimate action of his own conscience, a terrible machinery had been brought to bear—and was still operating—on Mr. Dimmesdale’s well-being and repose. Knowing what this poor, fallen man had once been, her whole soul was moved by the shuddering terror with which he had appealed to her—the outcast woman—for support against his instinctively discovered enemy. She decided, moreover, that he had a right to her utmost aid. Little accustomed, in her long seclusion from society, to measure her ideas of right and wrong by any standard external to herself, Hester saw—or seemed to see—that there lay a responsibility upon her in reference to the clergyman, which she owed to no other, nor to the whole world besides. The links that united her to the rest of humankind—links of flowers or silk or gold, or whatever the material—had all been broken. Here was the iron link of mutual crime, which neither he nor she could break. Like all other ties, it brought along with it its obligations.

Hester Prynne did not now occupy precisely the same position in which we beheld her during the earlier periods of her ignominy. Years had come and gone. Pearl was now seven years old. Her mother, with the scarlet letter on her breast glittering in its fantastic embroidery, had long been a familiar object to the townspeople. As is apt to be the case when a person stands out in any prominence before the community, and at the same time, interferes neither with public nor individual interests and convenience, a species of general regard had ultimately grown up in reference to Hester Prynne. It is to the credit of human nature, that—except where its selfishness is brought into play—it loves more readily than it hates. Hatred, by a gradual and quiet process, will even be transformed to love, unless the change be impeded by a continually new irritation of the original feeling of hostility. In this matter of Hester Prynne, there was neither irritation nor irksomeness. She never battled with the public, but submitted uncomplainingly to its worst usage. She made no claim upon it in requital for what she suffered—she did not weigh upon its sympathies. Then also, the blameless purity of her life during all these years in which she had been set apart to infamy was reckoned largely in her favor. With nothing now to lose in the sight of mankind, and with no hope—and seemingly no wish—of gaining anything, it could only be a genuine regard for virtue that had brought back the poor wanderer to its paths.

The Murder, by Paul Cézanne, 1868. Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool, England.

It was perceived, too, that while Hester never put forward even the humblest title to share in the world’s privileges—further than to breathe the common air and earn daily bread for little Pearl and herself by the faithful labor of her hands—she was quick to acknowledge her sisterhood with the race of man whenever benefits were to be conferred. None so ready as she to give of her little substance to every demand of poverty—even though the bitter-hearted pauper threw back a gibe in requital of the food brought regularly to his door, or the garments wrought for him by the fingers that could have embroidered a monarch’s robe. None so self-devoted as Hester when pestilence stalked through the town. In all seasons of calamity, indeed, whether general or of individuals, the outcast of society at once found her place. She came not as a guest but as a rightful inmate into the household that was darkened by trouble, as if its gloomy twilight were a medium in which she was entitled to hold intercourse with her fellow creatures. There glimmered the embroidered letter, with comfort in its unearthly ray. Elsewhere the token of sin, it was the taper of the sick chamber. It had even thrown its gleam in the sufferer’s hard extremity across the verge of time. It had shown him where to set his foot, while the light of earth was fast becoming dim and ere the light of futurity could reach him. In such emergencies, Hester’s nature showed itself warm and rich—a wellspring of human tenderness, unfailing to every real demand and inexhaustible by the largest. Her breast, with its badge of shame, was but the softer pillow for the head that needed one. She was self-ordained a Sister of Mercy; or, we may rather say, the world’s heavy hand had so ordained her, when neither the world nor she looked forward to this result. The letter was the symbol of her calling. Such helpfulness was found in her—so much power to do, and power to sympathize—that many people refused to interpret the scarlet a by its original signification. They said that it meant “Able”—so strong was Hester Prynne, with a woman’s strength.

It was only the darkened house that could contain her. When sunshine came again, she was not there. Her shadow had faded across the threshold. The helpful inmate had departed without one backward glance to gather up the meed of gratitude, if any were in the hearts of those whom she had served so zealously. Meeting them in the street, she never raised her head to receive their greeting. If they were resolute to accost her, she laid her finger on the scarlet letter and passed on. This might be pride, but was so like humility that it produced all the softening influence of the latter quality on the public mind. The public is despotic in its temper; it is capable of denying common justice when too strenuously demanded as a right. But quite as frequently it awards more than justice, when the appeal is made—as despots love to have it made—entirely to its generosity. Interpreting Hester Prynne’s deportment as an appeal of this nature, society was inclined to show its former victim a more benign countenance than she cared to be favored with, or, perchance, than she deserved.

The rulers and the wise and learned men of the community were longer in acknowledging the influence of Hester’s good qualities than the people. The prejudices which they shared in common with the latter were fortified in themselves by an iron framework of reasoning that made it a far tougher labor to expel them. Day by day, nevertheless, their sour and rigid wrinkles were relaxing into something which, in the due course of years, might grow to be an expression of almost benevolence. Thus it was with the men of rank, on whom their eminent position imposed the guardianship of the public morals. Individuals in private life, meanwhile, had quite forgiven Hester Prynne for her frailty; nay, more, they had begun to look upon the scarlet letter as the token, not of that one sin, for which she had borne so long and dreary a penance, but of her many good deeds since. “Do you see that woman with the embroidered badge?” they would say to strangers. “It is our Hester—the town’s own Hester—who is so kind to the poor, so helpful to the sick, so comfortable to the afflicted!” Then, it is true, the propensity of human nature to tell the very worst of itself, when embodied in the person of another, would constrain them to whisper the black scandal of bygone years. It was nonetheless a fact, however, that in the eyes of the very men who spoke thus, the scarlet letter had the effect of the cross on a nun’s bosom. It imparted to the wearer a kind of sacredness, which enabled her to walk securely amid all peril. Had she fallen among thieves, it would have kept her safe. It was reported, and believed by many, that an Indian had drawn his arrow against the badge, and that the missile struck it and fell harmless to the ground.

The effect of the symbol—or rather of the position in respect to society that was indicated by it—on the mind of Hester Prynne herself was powerful and peculiar. All the light and graceful foliage of her character had been withered up by this red-hot brand and had long ago fallen away, leaving a bare and harsh outline, which might have been repulsive, had she possessed friends or companions to be repelled by it. Even the attractiveness of her person had undergone a similar change. It might be partly owing to the studied austerity of her dress, and partly to the lack of demonstration in her manners. It was a sad transformation too, that her rich and luxuriant hair had either been cut off or was so completely hidden by a cap that not a shining lock of it ever once gushed into the sunshine. It was due in part to all these causes, but still more to something else—that there seemed to be no longer anything in Hester’s face for Love to dwell upon; nothing in Hester’s form, though majestic and statue-like, that Passion would ever dream of clasping in its embrace; nothing in Hester’s bosom to make it ever again the pillow of Affection. Some attribute had departed from her, the permanence of which had been essential to keep her a woman. Such is frequently the fate and such the stern development of the feminine character and person when the woman has encountered—and lived through—an experience of peculiar severity. If she be all tenderness, she will die. If she survive, the tenderness will either be crushed out of her or—and the outward semblance is the same—crushed so deeply into her heart that it can never show itself more. The latter is perhaps the truest theory. She who has once been woman, and ceased to be so, might at any moment become a woman again if there were only the magic touch to effect the transfiguration. We shall see whether Hester Prynne were ever afterward so touched, and so transfigured.

Much of the marble coldness of Hester’s impression was to be attributed to the circumstance that her life had turned, in a great measure, from passion and feeling to thought. Standing alone in the world—alone as to any dependence on society and with little Pearl to be guided and protected—alone and hopeless of retrieving her position, even had she not scorned to consider it desirable, she cast away the fragments of a broken chain. The world’s law was no law for her mind. It was an age in which the human intellect, newly emancipated, had taken a more active and a wider range than for many centuries before. Men of the sword had overthrown nobles and kings. Men bolder than these had overthrown and rearranged—not actually, but within the sphere of theory, which was their most real abode—the whole system of ancient prejudice, wherewith was linked much of ancient principle. Hester Prynne imbibed this spirit. She assumed a freedom of speculation, then common enough on the other side of the Atlantic, but which our forefathers, had they known it, would have held to be a deadlier crime than that stigmatized by the scarlet letter. In her lonesome cottage by the seashore, thoughts visited her, such as dared to enter no other dwelling in New England—shadowy guests that would have been as perilous as demons to their entertainer, could they have been seen so much as knocking at her door.

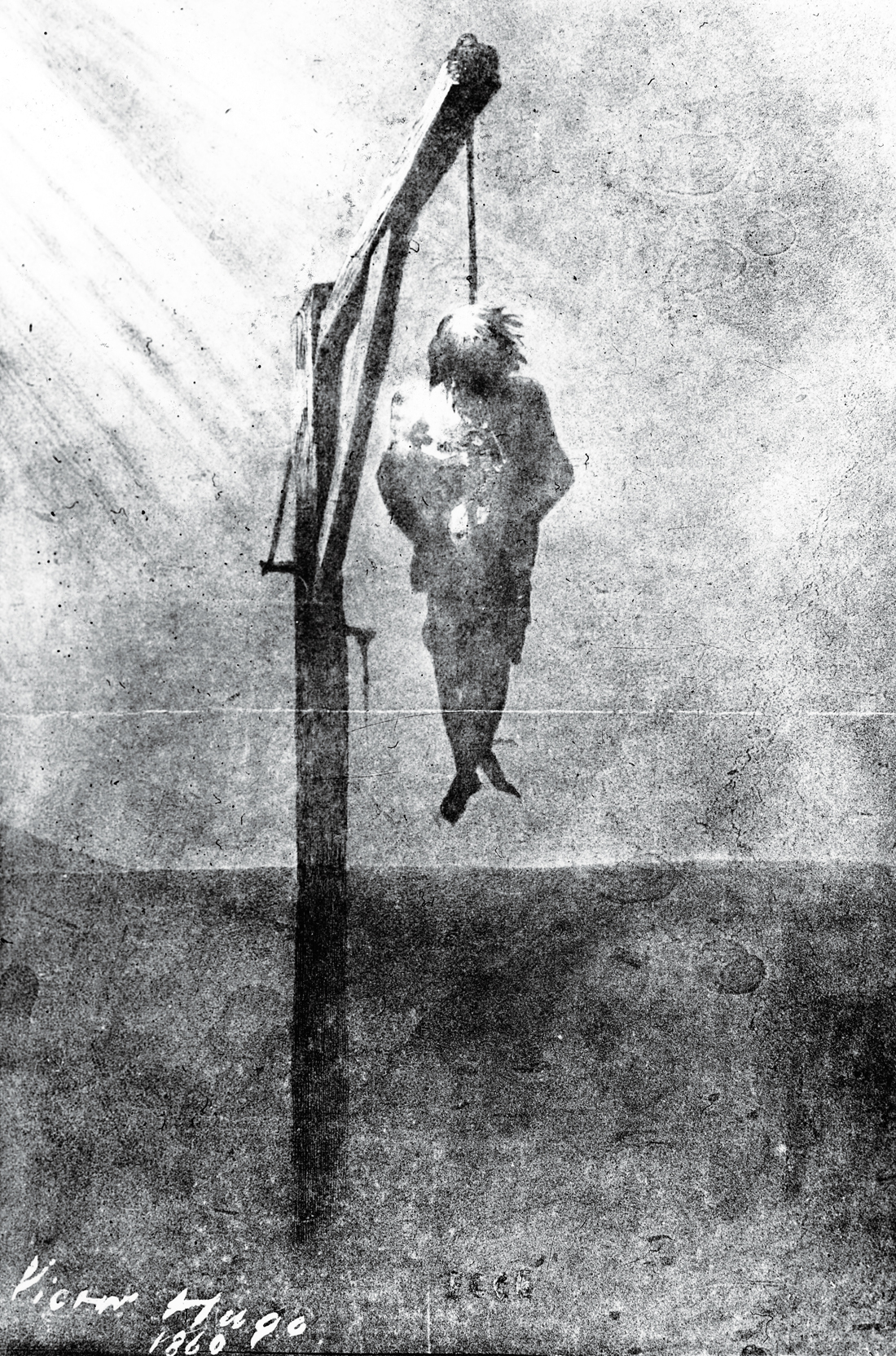

The Hanged Man or John Brown, by Victor Hugo, 1860.

It is remarkable that persons who speculate the most boldly often conform with the most perfect quietude to the external regulations of society. The thought suffices them without investing itself in the flesh and blood of action. So it seemed to be with Hester. Yet, had little Pearl never come to her from the spiritual world, it might have been far otherwise. Then she might have come down to us in history, hand in hand with Ann Hutchinson, as the foundress of a religious sect. She might in one of her phases, have been a prophetess. She might, and not improbably would, have suffered death from the stern tribunals of the period for attempting to undermine the foundations of the Puritan establishment. But, in the education of her child, the mother’s enthusiasm of thought had something to wreak itself upon. Providence, in the person of this little girl, had assigned to Hester’s charge the germ and blossom of womanhood, to be cherished and developed amid a host of difficulties. Everything was against her. The world was hostile. The child’s own nature had something wrong in it, which continually betokened that she had been born amiss—the effluence of her mother’s lawless passion—and often impelled Hester to ask in bitterness of heart whether it were for ill or good that the poor little creature had been born at all.

Man punishes the action, but God the intention.

—Thomas Fuller, 1732Indeed, the same dark question often rose into her mind with reference to the whole race of womanhood. Was existence worth accepting, even to the happiest among them? As concerned her own individual existence, she had long ago decided in the negative and dismissed the point as settled. A tendency to speculation, though it may keep woman quiet—as it does man—yet makes her sad. She discerns, it may be, such a hopeless task before her. As a first step, the whole system of society is to be torn down and built up anew. Then, the very nature of the opposite sex, or its long hereditary habit, which has become like nature, is to be essentially modified before woman can be allowed to assume what seems a fair and suitable position. Finally, all other difficulties being obviated, woman cannot take advantage of these preliminary reforms until she herself shall have undergone a still mightier change, in which, perhaps, the ethereal essence wherein she has her truest life will be found to have evaporated. A woman never overcomes these problems by any exercise of thought. They are not to be solved—or only in one way. If her heart chance to come uppermost, they vanish. Thus, Hester Prynne, whose heart had lost its regular and healthy throb, wandered without a clew in the dark labyrinth of mind—now turned aside by an insurmountable precipice, now starting back from a deep chasm. There was wild and ghastly scenery all around her and a home and comfort nowhere. At times, a fearful doubt strove to possess her soul, whether it were not better to send Pearl at once to heaven and go herself to such futurity as Eternal Justice should provide.

The scarlet letter had not done its office.

Nathaniel Hawthorne

From The Scarlet Letter. Nathaniel Hawthorne added the “w” to his surname in his early twenties, perhaps to dissociate himself from his great-grandfather John Hathorne, a presiding judge in the Salem Witch Trials. His published novels include The House of the Seven Gables, The Blithedale Romance, and The Marble Faun. Hawthorne died at the age of fifty-nine in 1864.