Imagine a number of men in chains, all under sentence of death, some of whom are each day butchered in the sight of the others; those remaining see their own condition in that of their fellows and, looking at each other with grief and despair, await their turn. This is an image of the human condition.

—Blaise Pascal, 1669Between Method and Execution

Disposing of the Romanovs.

On the morning of July 15, Comrade Filipp Goloshchekin arrived and said that things had to be finished off tomorrow. It was said that Tsar Nikolai was to be executed and that we should officially announce it—but when it came to the tsar’s family, then perhaps it would be announced, but no one knew yet how, when, and in what manner. Thus, everything demanded the utmost care and as few people as possible—moreover, absolutely dependable ones.

I immediately undertook preparations, for everything had to be done quickly. I decided to assemble the same number of men as there were people to be shot, gathered them all together, and told them what was happening—that they had to prepare themselves for this, that as soon as we got the final order, everything was going to have to be ably handled. You see, it has to be said that shooting people isn’t the easy matter that it might seem to some.

On the morning of the sixteenth, I prepared twelve Nagant revolvers and determined who would shoot whom. Comrade Filipp warned me that a truck would arrive at midnight. Those who arrived would give a password—they would be allowed in and would be given the corpses, which they would take away for burial. Around eleven o’clock that night, I gathered the men together again, gave out the revolvers, and stated that we would soon begin liquidating the prisoners. I warned Pavel Medvedev about the thorough check of the sentries outside and in, about how he and the guard commander should be on watch themselves in the area around the house and about how they should keep in contact with me. Only at the last minute, when everything was ready for the shooting, were they to warn all the sentries as well as the rest of the detachment that if they heard shots coming from the house, they shouldn’t worry and shouldn’t come out of their lodgings.

Massacre of the Innocents, by Giotto di Bondone, c. 1305. Scrovegni Chapel, Padua, Italy.

The truck did not show up until half past one in the morning. After I learned that it was on its way, I went to wake the prisoners. Gathering everybody consumed a lot of time, about forty minutes. When the family was dressed, I led them to a room in the downstairs part of the house that had been previously selected by myself and my aide Comrade Nikulin. We had thought this plan through, but it must be said that when we conceived it, we did not think about the fact that, one, the windows would not be able to contain the noise; two, that the victims would be standing next to a brick wall; and finally, three (it was impossible to foresee this), that the firing would occur in an uncoordinated way. That should not have happened. Each man had one person to shoot, and so everything should have been all right. The causes of the disorganized firing became clear later. Although I told the victims that they did not have to take anything with them, they collected various small things—pillows, bags, and so on, and, I think, a small dog.

Having gone down to the room (at the entrance to the room, on the right there was a very wide window), I ordered them to stand along the wall. Obviously, at that moment they did not imagine what awaited them. The tsar’s wife, Alexandra Fyodorovna said, “There are not even chairs here.” Tsar Nikolai was carrying their son Alexei. He stood in the room with him in his arms. Then I ordered a couple of chairs. On one of them, to the right of the entrance, almost in the corner, Alexandra Fyodorovna sat down. The daughters and the maid Demidova stood next to her, to the left of the entrance. Beside them Alexei was seated in the armchair. Nikolai stood opposite Alexei. At the same time I ordered the men to go down and to be ready in their places when the command was given. Nikolai had put Alexei on the chair and stood in such a way that he shielded him. Alexei sat in the left corner from the entrance, and so far as I can remember, I said to Nikolai approximately this: his royal and close relatives inside the country and abroad were trying to save him, but the Soviet of Workers’ Deputies resolved to shoot them. He asked, “What?” and turned toward Alexei. At that moment I shot and killed him outright. He did not get time to face us to get an answer. At that moment disorganized firing began. The room was small, but everybody could come in and carry out the shooting according to the set order. But many shot through the doorway. Bullets began to ricochet because the wall was brick. Moreover, the firing intensified when the victims’ shouts arose. I managed to stop the firing but with great difficulty.

A bullet, fired by somebody in the back, hummed near my head and grazed either the palm or finger (I do not remember) of somebody. When the firing stopped, it turned out that the daughters, Alexandra Fyodorovna, and, I think, Demidova and Alexei, too, were alive. I think they had fallen from fear or maybe intentionally, and so they were alive. Then we proceeded to finish the shooting. (Previously I had suggested shooting at the heart to avoid a lot of blood.) Alexei remained sitting petrified. I killed him. They shot the daughters but did not kill them. Then Comrade Yermakov resorted to a bayonet, but that did not work either. Finally they killed them by shooting them in the head. Only in the forest did I finally discover the reason why it had been so hard to kill the daughters and Alexandra Fyodorovna.

After the shooting it was necessary to carry away the corpses to the truck, but it was a comparatively long way. How could we do it? Somebody came up with an idea: stretchers. (We did not think about it earlier.) We took shafts from the sledges and, I think, put sheets on them. Having confirmed they were dead, we began to carry them out.

After instructions were given to wash and clean everything, at about three o’clock or even a little later, we left. I took several men from the internal guards. I did not know where the corpses were supposed to be buried. Filipp Goloshchekin had assigned that to Comrade Yermakov. Yermakov drove us somewhere out to the Verkh-Isetsky Works. I had never been at that place and did not know it. At about two or three versts (or maybe more) from the Verkh-Isetsky Works, a whole escort of people on horseback or in carriages met us. I asked Yermakov who these people were, why they were there. He answered that he had assembled those people. I still do not know why there were so many. I heard only shouts: “We thought they would come here alive, but it turns out they are dead.” Also, I think, about three or four versts farther, our truck got stuck between two trees. There where we stopped, several of Yermakov’s people were stretching out girls’ blouses. We discovered that there were valuables and they were taking them. I ordered that men be posted to keep anyone from coming near the truck.

The truck was stuck and could not move. I asked Yermakov, “Is it still far to the chosen place?” He said, “Not far, beyond railroad beds.” And there behind the trees was a marsh. Bogs were everywhere. I wondered why he had herded in so many people and horses. If only there had been carts instead of carriages. But there was nothing we could do. We had to unload to lighten the truck, but that did not help. Then I ordered them to load the carriages because it was already light, and we did not have time to wait any longer. Only at daybreak did we come to the famous “gully.” Several steps from the mine, where the burial had been planned, peasants were sitting around the fire, apparently having spent the night at the hayfield. On the way we met several people. It became impossible to carry on our work in sight of them. It must be said, the situation had become difficult.

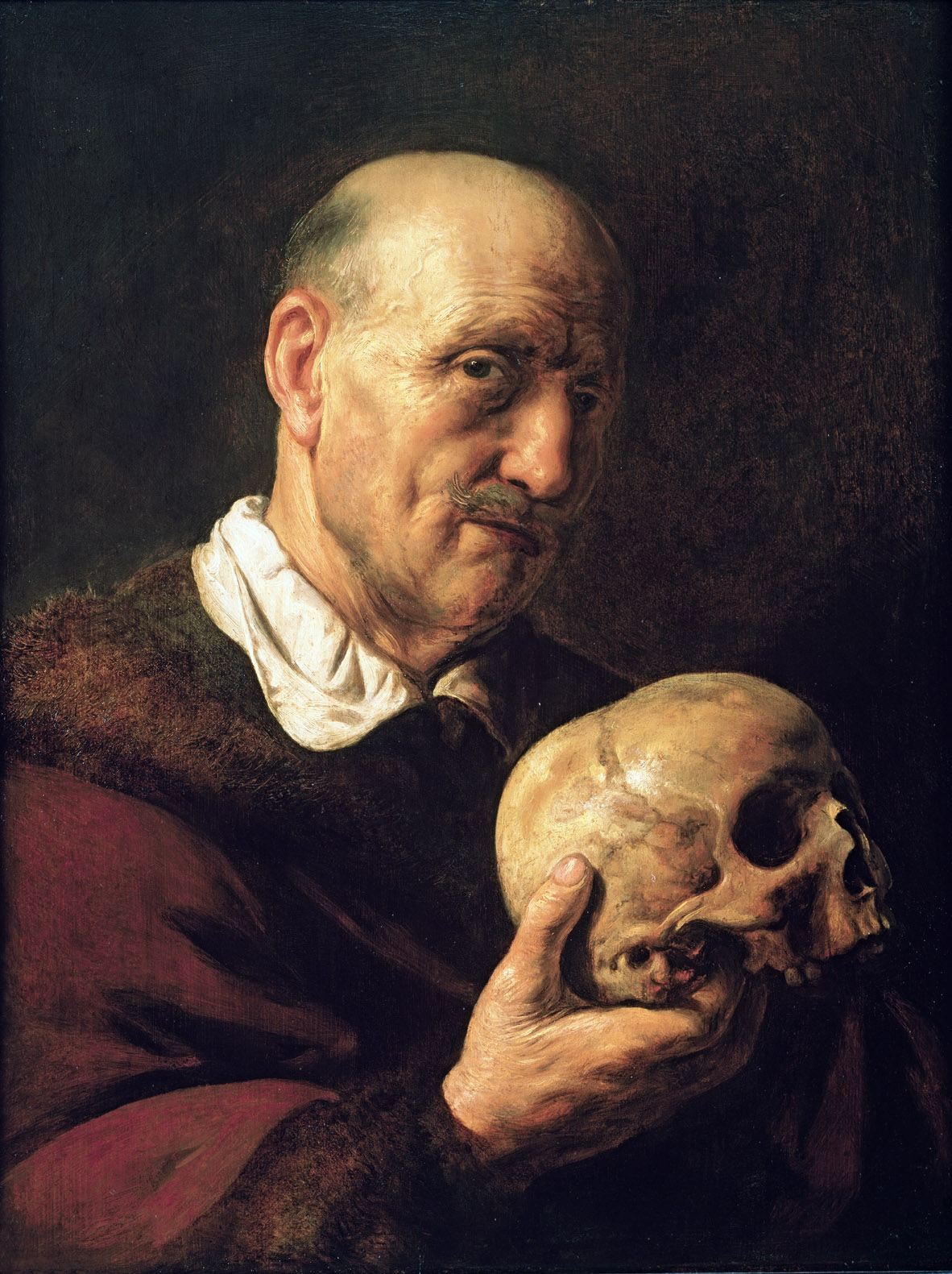

Vanitas, by Jan Lievens, c. 1640.

I ordered the men to turn back anybody to the village and to shoot any stubborn, disobedient persons if that did not work. Another group of men was sent to the town because they were not needed. Having done all of this, I ordered the men to load the corpses and to take off the clothes for burning, that is, to destroy absolutely everything they had, to remove any additional incriminating evidence if the corpses were somehow discovered. I ordered bonfires. When we began to undress the bodies, we discovered something on the daughters and on Alexandra Fyodorovna. I do not remember exactly what she had on, the same as was on the daughters or simply things that had been sewed on. But the daughters had on bodices almost entirely of diamonds and other precious stones. Those were not only places for valuables but protective armor at the same time. That is why neither bullets nor bayonets got results.

The valuables had been collected, the things had been burned, and the completely naked corpses had been thrown into the mine. From that very moment new problems began. The water just barely covered the bodies. What should we do? We had the idea of blowing up the mines with bombs to cover them, but nothing came of it. At about two p.m. I decided to go to the town because it was clear that we had to extract the corpses from the mine and to carry them to another place. Even the blind could discover them. Besides, the place was exposed. People had seen something was going on there. I set up posts, guards in place, and took the valuables and left. I went to the regional executive committee and reported to the authorities how bad things were. Comrade Safarov and somebody else (I do not remember who) listened but said nothing. Then I found Filipp Goloshchekin and explained to him we had to transfer the corpses to another place. When he agreed, I proposed to send people to raise the corpses. At the same time I ordered him to take bread and food because the men were hungry and exhausted, not having slept for about twenty-four hours.

Yakov Yurovsky

From his account of the execution of the Romanov family. Following the riots in Petrograd in March 1917, Nikolai II’s abdication, and the success of the Bolshevik Revolution, the Romanovs were taken in April 1918 to the Ural Mountains and guarded by Bolsheviks. It is believed that Yurovsky, a Bolshevik officer who had joined the party in 1905, had received an order for the Romanovs’ execution from Vladimir Lenin. The Russian Orthodox Church canonized the former tsar and his family in 2000, placing them at the lowest rank of sainthood, “passion bearers.”