What touches all shall be approved by all.

—Edward I, 1295

Study for The House of Representatives, by Samuel F.B. Morse, c. 1821. Smithsonian American Art Museum, museum purchase through a grant from the Morris and Gwendolyn Cafritz Foundation, 1978.

It takes a lot of gall to represent anyone else, even in so humble a thing as a school board, much less in the U.S. House, and less still in our U.S. Senate, with all its gaseous grandees. In the now plutocratic United States, once in theory so free of caste, it’s still hard to bear why anyone should be above you and me, with the right to “represent” us on the issues of the day. When I ran in the House primary in 2009 and got clobbered, I used to wonder: How could I justify going to Washington, DC, for two years and claiming to represent 600,000 people back in Chicago? It seemed all the more illegitimate since, in the special election to fill Rahm Emanuel’s seat, only 50,000 of that number voted. I would brood about it in the backseat of the car when Matt—who was hired as my “body man”—was driving me around from Catholic fish fry to mosque to synagogue. How could I legitimately represent the working-class voters whose sorrows can be so much different and greater than my own?

Of course, it’s been a problem since the start of the republic—the legitimacy of a tiny few in the learned classes voting for the many—but at least in 1789 there were only 4 million Americans. Minus the enslaved and women, that leaves about 1.5 million. Even in New York City, with 33,000 people, Hamilton and Burr between them may have known a third of the white male constituents, at least by sight. As the population has risen from 3 million in 1789 to 330 million today, we may have passed the limit of viable representation. It’s all the more troubling that many of those people with sorrows greater than my own either will not or cannot or just don’t have the capacity to vote—in effect, to be represented. After all, in the U.S. presidential election of 2016, over 100 million eligible voters failed to participate. With so many not voting, it is arguable if such an election outcome is even legitimate.

The old representative democracy is starting to crack up. In its place there is a digital or direct democracy. By email or tweet, small bands of vigilantes can track down our representatives and cling, Fury-like, until they vote the right way. Is this the mob rule that Aristotle in the Politics feared? I can imagine the fear—the sense of being chased online—that has made just about every GOP legislator line up behind Trump. When my former neighbor John Cullerton retired as president of the Illinois state senate, he talked to the Chicago Tribune about the effects of such “digitalization.” “It’s the difference from a representative democracy to a direct democracy,” he explained. “So the old model for voters is, ‘I’m busy, I’m hiring you. Go down to Springfield. Listen to testimony. Make your informed decisions. Every two years I’ll check on you.’ And now you just go directly to the legislator, who says, ‘We don’t need to listen to testimony. I got five hundred emails and five thousand tweets retweeted saying I’ve got to vote for this bill.’ ”

The old divide between Edmund Burke and Thomas Paine over how a legislator should represent the people is now hopelessly out of date. For Burke, legislators belonged to the elite and were perfectly justified in making decisions for the landed squires who were their constituents—never mind the poachers and starving rural poor Burke’s constituents used to hang. For them—really, the vast majority—Burke thought it enough to give them “virtual” representation. As he put it, “Your representative owes you not his industry only but his judgment, and he betrays, instead of serving you, if he sacrifices it to your opinion.” For Paine, legislators should be transparent and have no existence apart from channeling the voice of the people, which they could hear because they themselves were part of the common people.

But the virtual republic has ended Burke’s form of virtual representation, which was really just the representation of one particular man. As for Paine’s version, it is hard to channel the voice of almost 330 million people, especially in a deeply polarized nation. Is it ever legitimate to claim to be the voice of the people? Almost a third of the people—the 100 million who sat out 2016—didn’t vote. Of those who did, almost half are for Trump, and they don’t want to be the voice, because Trump has to be the voice.

So here’s how I decided—in the backseat of the car—was the right way to represent the people: being a union-side labor lawyer, I’d go to DC and try to give people the capacity to make their own decisions. It’s not just to increase the capacity to decide but to increase their own capabilities to make decisions. Organized labor at its best—when most in touch with its original democratic mission—tries to get more people to make decisions at work, so they learn to make better decisions in the workplace, in the schools, in their communities. It’s what legislators should do—give people as much practical governing experience as they can, so that the represented may better discern who should represent them. Then they can also make better decisions about how much they need the rest of us to represent them.

Sure, in my own way, I’m being Burke or Paine, too. I’m claiming my own right to push this point of view. But for me, at least, of all the ways to represent people, this seems to be the most legitimate: pull them into the work of governing in the hope of eliminating the political infantilism that has left the country in so sorry a state.

As a representative, I should make sure everyone is capable of replacing me in office by giving them some of the work of the state. Is that impossible? Maybe, but it’s the right goal to have if we as a people are to learn again how to govern ourselves. After the poison of the Trump era, we will have to detoxify the country. We may need a modern form of “reconstruction,” like the original Reconstruction attempted after the Civil War. And while this reconstruction, like the first, may have to be constitutional in part, it also has to be moral. It is crucial that we make our government more of a genuine republic, based on pure, untainted “one person, one vote.” Yes, we have to end the minority rule that has kept a minority party like the GOP in power—in the gerrymandered House, in a Senate that gives North Dakota the same control over the country as California, and a presidency that goes to the runner-up. Then there’s the matter of the Supreme Court, which the GOP has packed, just as the dying Federalist Party packed the courts in 1801 before the Jeffersonians came roaring in.

View of the Issuance of the Constitution, by Baiju Kunitoshi, 1889. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, gift of Lincoln Kirstein, 1960.

Here’s what few grasp: a serious change in our form of government can take place by simple majority vote of the two houses of Congress. The Constitution allows for some informal “amending” of itself. By simple majority vote, for example, Congress can end gerrymandering of the House. It has an express power to override every state election rule under article 1, section 4 (the Elections Clause). It can do so for state legislatures by its power under section 5 of the Fourteenth Amendment to enforce the Equal Protection Clause applicable to the states in section 1. As for fixing the imbalance in the Senate, Congress by a simple majority could also admit the District of Columbia and Puerto Rico as states. That’s how we admit every state: it is not by a two-thirds vote.

Yes, under our wacky form of representation, North Dakota could still cancel out California. But by admitting Puerto Rico and DC, at least we could balance the “free states” and the “slave states,” as we used to do. We can make the Senate a bit more blue and a bit less red, as the lineup of rotten boroughs will better mimic the people of the nation. And by majority vote, Congress could drive a stake through the heart of the Electoral College. It could require each state to allocate its electors based on the proportion of votes by the people for the presidential candidate. Yes, article 2, section 1 says the states control the process and can “appoint” electors, but that went out with the Civil War. Section 2 of the Fourteenth Amendment refers expressly to the right of the people to vote for president. Again, section 5 of the same amendment says Congress can make laws to enforce or prescribe the scope of that right. And to make the republic even more representative, Congress by majority vote can place term limits on Supreme Court justices. Article 3 says judges “shall hold their offices during good behavior” but that the “original intent” was to protect against arbitrary removal for political reasons—to keep the courts from becoming political. A term limit applied neutrally is not prohibited and even promotes that original intent to stop the politicizing of courts.

Such a structural rehab, though, is far from enough. We have to change our notion as to what representative governments should do. What will justify representing the people is to increase their capacity to pick who represents them. The task of representative government is to reintroduce Trump voters, and nonvoters, into the norms of democratic citizenship.

One thing should be clear: more formal education is not the answer. Never have Americans had so much formal education, and almost half of white male college graduates turned over the country to a buffoon. To be sure, we need education. But it is education on the job. What legitimate representative government must do after Trump is to give people the chance to do the work of the state. It’s to give everyone a chance to hold some kind of office.

It’s not a matter of compelling anyone to do civic work—at least not at the current stage of the burning of the planet. No, it’s a matter of creating a form of representation that opens the work of our republic to everyone, with or without a college degree. It’s not to turn citizens into public “employees”—we have enough public employees, at least at the state and local levels—but rather to let more of us perform an “office” and be accountable for something. In Walt Whitman’s vision of democracy, we can create a union where we exchange or confer gifts on one another by the particular work we do. Whitman was describing a solidarity that came out of our exchanges with each other in the commercial world. That’s what he saw in “Crossing Brooklyn Ferry.” Now, in the time of Apple and Google, these small individual exchanges have to take place in the public realm. It’s the only place where we can create the common life.

Yes, it has a mystical dimension, and it may sound dreamy and Whitman-like, but in real life it is just getting back to what made the New Deal such a success—the way Franklin D. Roosevelt gave people something to do. That was the political magic, not the Social Security check (the first one of which did not arrive until 1940) but the genius in having just about anyone walk in, without any fuss, and become part of the state or perform some office related to the New Deal. That’s what recovered a capacity for self-government just in time for World War II. That’s what helps explain why Philip Roth’s The Plot Against America is a work of fiction, not history.

Of course, it helped that there was a state of emergency in the 1930s. Still, ordinary people could sign up for work with the Civilian Conservation Corps or the Works Progress Administration. They could take part in cooperatives and people-based initiatives such as rural electrification and soil conservation, which were especially crucial in rural areas, where now there is so little to do and not much exchanging of gifts with those of us in the global cities. The New Dealers pulled people into dozens of projects and classes. Not just in FDR’s New York but also in Alf Landon’s Kansas, this led to a sense of being part of the state.

An election is coming. Universal peace is declared, and the foxes have a sincere interest in prolonging the lives of the poultry.

—George Eliot, 1866But the biggest way that people felt part of the state was that it was part of the New Deal project to get everyone into a union. People in the 1930s working in the big plants and mills of the Midwest could just sign up. In the coalfields John L. Lewis had his organizers handing out flyers: “The president wants you to join the United Mine Workers.” While labor unions belong to civil society, not the state, the mass unionism of the early New Deal had some of the character of a state project. At the same time, the burst of organizing from the newly formed Congress of Industrial Organizations, which led to mass sit-downs in the steel, auto, and rubber industries, was due to a wide-open unionism, a world away from the legalistic way we determine exclusive union representation today. Anyone could be a union member, shop steward, strike leader, or union leader, whether there was an officially certified union or not. It is a paradox, I suppose, that this so-called minority or members-only unionism came at a time when labor was most like a mass movement. Employers had to negotiate not because a majority had voted for the union in an official election but because the workers had simply taken over the plant. It is impossible to count the new offices that were open to anyone, regardless of education; in the minds of many, it was reasonable to feel they were doing the work of the New Deal.

It’s quite possible to do that again with a radical new way of representing working people. Congress could require German-style works councils in firms of over a hundred employees. Such councils are directly elected by workers whether there are unions or not. Or it could require codetermination, as Elizabeth Warren and others have proposed—that is, direct election by workers of directors on corporate boards. Or Congress could require unions, period: it could start by requiring all federal contractors to have union representation. In that way, we could multiply the number of offices that people could hold, and do so in the workplace. In the novelty of all these new offices—and the ease of holding them, by legal right—there are still ways we could use labor law to give people a sense of being part of the state.

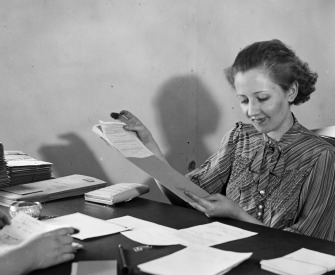

Labor organizer Edith Berkman being arrested during a textile workers’ strike, Lawrence, Massachusetts, 1933. JT Vintage / Art Resource, NY.

To be sure, people are out of the habit of joining unions, or of having any say over their conditions of work at all. It may be people no longer have the nerve they did in the 1930s. That’s why, as a matter of federal policy, it may be necessary to require it. After all, it serves an interest of the state. The old case for labor, made in books like The New Industrial State by John Kenneth Galbraith, was to create a “countervailing power” to oligarchic big business. It’s still a valid interest of the state—even more so in the extreme inequality of the time.

But the new case for labor is to countervail the power an antidemocratic right wing has acquired in the Trump era within the white working class. We need to create leaders within the working class who are able to talk back to people who talk like Trump. Remember Trump came to power by saying at his acceptance speech at the 2016 GOP convention, “I will be your voice.” He has had a genius for getting so many in the white working class to internalize that voice, which they now hear all day, thanks to Twitter and Fox. In the post-Trump era, we will need to create, at least in this white working class, a countervailing voice. We need more high school grads to have voices of their own.

Of course, one may object that so many union members are already for Trump, but that’s misleading, as there is so little left of labor. It’s 6 percent of the private sector—it’s the building trades, in shrunken form, and the most conservative part of labor. It is now much like the labor that existed before the New Deal. Or they are a high-income elite like airline pilots, so many of whom came out of the military. Let’s put aside the argument that a New Deal expansion of labor would bring down the high inequality that makes a commitment to a republic so tenuous. The moral argument here is that it is the best mechanism for the multiplication of offices, even for those without high school diplomas, and giving people the capacity for the reality-based thinking we need as a people to govern ourselves again.

But in what other way can people have that sense of sharing in the work of government? After all, we may never have to start a national government from scratch as we did during the New Deal. Today the work of government is professionalized, with boundaries to keep out amateurs and volunteers. During the Clinton and Obama administrations, there was no real effort to pull in people, and the federal government itself has become weaker as a result. There was nothing for ordinary citizens to do.

Many of the offices of citizenship seen in Whitman’s day have disappeared. To be sure, there are still juries and jury duty, though at least in federal courts judges have tried hard to do away with juries in virtually all civil cases. In law school I had been led to believe everything went to a jury, but it’s been about two decades since I last had a jury on a federal civil case. It’s not just that juries have disappeared but that what they’re asked to do has changed. In Whitman’s day juries not only decided facts but often decided law or even what the law should be. What is now called jury nullification—instances where juries ignore the law to do what they thought was right—was not an exception but a norm. Now it is unthinkable that we would let ordinary people make legislative-type decisions in particular cases. Instead we have elite federal judges, who govern the country from Yale and Harvard the way the proconsuls sent out by Rome used to run the empire. There are no offices like those where ordinary people a hundred years ago could make the kind of day-to-day governing decisions only a judicial elite is allowed to execute today.

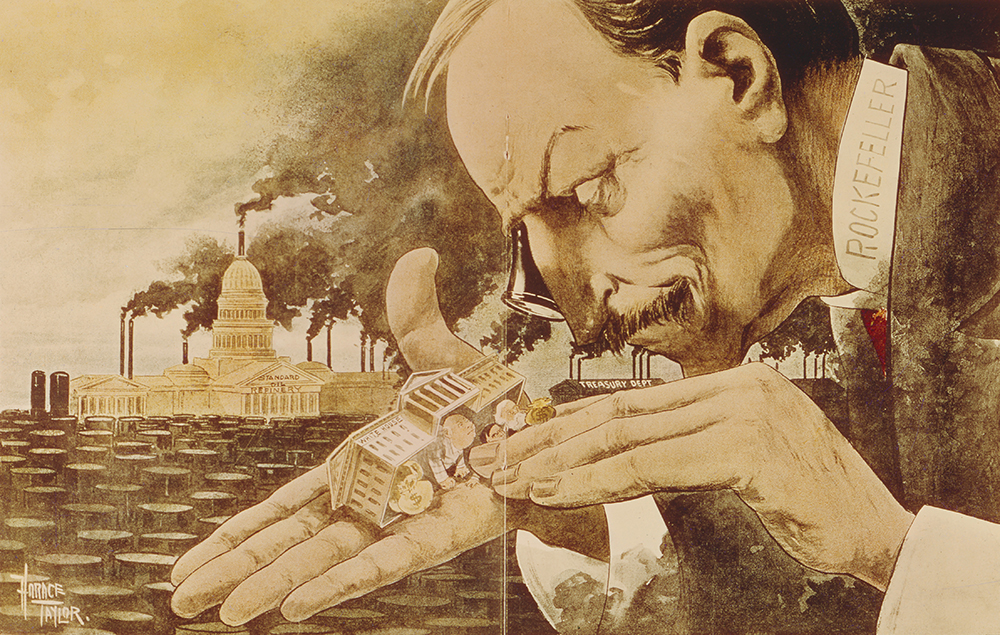

The Trust Giant’s Point of View, by Horace Taylor, 1900. Snark / Art Resource, NY.

Of course, the New Deal—unlike the Clinton and Carter administrations, for example—had the unfair advantage of being a response to catastrophe. The Obama administration had an opportunity to respond to catastrophe, but Obama’s failure to take on the filibuster or supermajority rule in the Senate allowed that opportunity to be lost. All those demons that the Roosevelt administration was able to hammer down went flying into the air. The financial crisis of 2007–8 brought out the worst in many of us, and the Obama administration made little effort beyond rhetoric to call out our best. To be sure, far more effectively than the New Deal in the 1930s, the Obama administration used Keynesian methods, or fiscal policy, to head off disaster. Yet its professional aplomb in doing so is just what removed the need to bring people to help volunteer and do informally the work of government. Consider the argument made by Rebecca Solnit in her 2009 book A Paradise Built in Hell: The Extraordinary Communities That Arise in Disaster. Though Solnit doesn’t say so, it might have been better if there had been no Keynesian fix. No “extraordinary communities” arose, and it was left to Obama to hold off all the anger from those left isolated—until, of course, one day there was Trump, and Obama was gone.

But now there are crises that may well multiply the offices that in a representative government only the represented can perform. In particular, even before the Covid-19 pandemic, we were facing two crises that call upon us to create “extraordinary communities” to carry out the work of the state.

First, the planet is already on fire—in fact, there’s not just fire but drought, hurricane, tornadoes, and flooding—and here is a disaster that Keynesian economics or monetary or fiscal policy is partly unable and partly too late to stop. This will be a new “Worst Hard Time,” to borrow the title of Timothy Egan’s 2006 book about the Dust Bowl. We will need “community,” an expansion of self-government, on a scale that would dwarf what took place in the 1930s. It seems that a democracy like ours is inherently unable to plan to head off a disaster like global warming. But democracies have a certain built-in advantage over authoritarian regimes at mobilizing when disaster comes. So the more we can start sharing the work of government, or multiplying offices, the better prepared we will be for Armageddons still to come. Part of a global response to global burning will be or should be citizen action at the local level, at least in our country, including ward or local organizations that give the people who join them the power to act as lawgivers and law enforcers—to be juries in the nineteenth-century sense as well as fire departments and block-by-block Red Crosses.

The ownership of private property itself may become an office. Instead of fee-simple ownership, with no duties to nonowners, the holding of property may in the future entail a responsibility to others. It would be as if every owner were a fiduciary. The day may come—when the increase in temperature is 2.5 or even 3 degrees Celsius—when each owner of property is a trustee who can be removed. Long before that, we will have to create our own little paradises or communities in which we help one another to higher ground. We will have to bring more people into doing the work of the state. It means pulling in the 100 million voters who sit out elections. In anticipation of these communities we have to create, we might start with a law for compulsory voting now.

Second, as the pandemic has helped us to see, our country is getting old—horribly old and infirm—on a scale that will have to change how we govern ourselves. In the decades ahead, with increased longevity and a falling birthrate, there will be too few “young,” or those under sixty-five, to take care of those over eighty-five, or at least to do so as full-time state or private-sector employees. In northern Europe there are already spontaneous “civic enterprises”—not sponsored by the state or set up by foundations—where capable citizens keep track of the elderly. As birthrates decline, we can’t pull people out of the workforce to do this kind of thing. While that used to be the work of the church, it is becoming the secular work of citizens volunteering to do some of the work of the welfare state.

In the meantime, what should we do as these two comets barrel down upon us? One comet has already landed upon us, a pandemic that may last well into 2021. It may change our form of government. By November we may have gone on to reelect Donald Trump. On the other hand, we may view the pandemic as a biblical judgment. In 1985, back in the Reagan era, Robert Neelly Bellah and his Habits of the Heart coauthors warned what might happen if the individualism in our culture went unchecked. They feared it would turn into a hyperindividualism, or narcissism, that would cut free of the Judeo-Christian morality that had always held it in check. If so, it is a fitting punishment for such runaway individualism that we now have to live in such isolation. Perhaps after it is over, after so much time spent so coiled up, we will be eager to spring into one another’s arms.

If the people be the governors, who shall be governed?

—John Cotton, 1636It is impossible—at the time I’m writing—to know what will happen. It is hard to talk of sharing the work of the state, or even civic voluntarism, when we are taking our temperature every morning. Still, a pandemic can create a radical form of equality. To me, as a union-side lawyer, I am slack-jawed that under the CARES Act, we treated independent contractors as employees, with benefits. It may mark the end of what David Weil deplored in The Fissured Workplace: Why Work Became So Bad for So Many and What Can Be Done to Improve It (2014). He was lamenting the “fissuring” of employees from their employers and their replacement with giglike independent contractors. But there has been a backlash in states like California to the gig economy. Besides, if there was a fissured workplace before Covid-19, it is being fissured to the advantage of many employees now, who can work remotely at home but still be on a payroll. It’s hard to believe that when the pandemic is over, we can go back to the long hours of the pre-Covid workplace, with cameras set up to watch us. Though we might have to wear masks, many of us may find it easier to breathe. The more we can limit the boss’ gaze, the more time that working people will have to live in the public realm.

And didn’t Aristotle claim that it’s in the public realm we live at the height of our powers? But in our present meritocracy, maybe fewer of us should be living at the height of our powers, for we are all too prone to glorify ourselves.

Right after I lost my race to get in the U.S. House, I had a stop on Mount Olympus, a chance to argue in the Supreme Court. Yes, I had a half hour of glory, chatting with the gods at the pinnacle of the republic, with nothing but the starry sky above. I felt so much more adult than I had a few months before—as one of a dozen candidates running for the House. I was often in a church basement where we each had sixty seconds to answer questions like “What would you do about the economy?” Every time I’d start to answer, it seemed a little girl would pop up waving a card: Fifteen Seconds! Then: Five Seconds! Then she’s jumping up and down, waving: Time’s Up!

I would sit down in despair. We may yet learn as a people how to govern ourselves again, but a card is being waved in front of us to say we’re running out of time.

This essay appears in Democracy, the Fall 2020 issue of Lapham’s Quarterly. The issue is made possible by a generous grant from the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation.