No woman needs intercourse; few women escape it.

—Andrea Dworkin, 1978

Venus of Urbino, by Titian, 1538. Uffizi Gallery, Florence, Italy.

In the spring of 2001, on the final night of an unsettling German book tour during which I had become convinced that evening after evening I was reading to different groups of catatonics bused in from the local mental hospital, I was staying at an appropriately eccentric hotel on a hilltop high above Zurich. The hotel—founded (or so I was told) in the previous century by group of Swiss women’s-temperance health nuts who had arranged matters so that twenty-first-century guests still couldn’t get a drink—seemed like the perfect culmination of a Kafkaesque travel experience. It was late. My husband and I were flying home the next morning, and we couldn’t sleep. We flipped through the TV channels, past the badly dubbed Steven Seagal action films and the ultraboring French talk shows, until at last we found an adult station broadcasting from Bavaria that seemed to offer some promise.

First came a slide show of blonde women, built like Wagnerian heroines, with escort-service phone numbers bannered across their prodigious breasts. Then a film clip began in which two go-go girls danced in a bar with zombielike affect, both blonde, shirtless, and wearing tiny leather miniskirts that they kept lifting up as they danced, and under which they were naked. This went on for quite a while—skirts up, skirts down—until it became as tedious as the French talk shows, only seedier and more depressing.

Except that there was one interesting detail, one element of the program that riveted our insomniac attention. In the background, behind the dancing girls, was a looped recording of Martin Luther King Jr. delivering his “I Have a Dream” speech.

Was the film erotic or pornographic? I would have to say: neither. It certainly didn’t reflect some sexy, sensual welling-up of the life force, and quite frankly, after seeing the film the last thing in the world that anyone (excepting, I suppose, a few Bavarian maniacs) would want to do is have sex.

Like many distinctions, the border separating the erotic from the pornographic has been blurred and redefined not by some natural evolution of culture and language, but by capitalism’s imperative to help the consumer readily locate the product he wants to buy. Beyond any meaning they once possessed, and beyond the connotations that still reward consideration, the words erotic and pornographic have by now become niche-marketing tags. They are designations like those in the film-rating system, employed to answer the logical questions any potential customer might sensibly ask: How naked? How deep? Which orifices? How much does it cost? Most important is the unspoken inquiry beneath every purchase decision: What do my desires reveal about who I am?

Erotic now connotes R-rated, edging toward the NC-17, while pornographic suggests the X. The harried office worker stopping by the bookstore for something to enliven a solitary weekend might be drawn to a volume entitled Best Erotic Fiction of 2008 but might shy away from an anthology of the year’s Best Pornographic Fiction, just as the business traveler, returning to the hotel after a day of stressful meetings, may hope to order some straight-up porn—as opposed to merely erotic cinema—on pay-per-view. Meanwhile, the nuances distinguishing the erotic from the pornographic have been reduced so that both locutions suggest nothing more than varying degrees and intensities of sexual content and arousal, much as those tiny chili peppers on the Sichuan menu promise or warn of heat and spice.

What’s been lost in the process is the broader meaning of the Greek word eros, and erotic, which have always included the sexual but have also suggested the mysterious, even metaphysical, connection between sex and life, sex and pleasure, the origin of life and the celebration of life.

If I were asked to design the curriculum for the junior-high sex education class of the future (obviously, a wishful fantasy predicated on a future that permits sex education), I might begin by telling students about the contrast, in Greek culture, between Eros and Thanatos, between the realms of life and death. I would explain that both are the names of Greek gods—the god of love and the god of death—and that to speak of the opposition between them is to address the conflict between the life force (sexuality, energy, vitality, the urge to create and procreate) and the death wish, the impulse that draws mankind, powerfully and perhaps inexorably, toward extinction, suicide, murder, and mass annihilation. I can see my imaginary students nodding off as I tell them that this conflict represents one of the cornerstones of Freudian psychology, but perhaps their interest might revive just a little if I asked them to watch the evening news and classify what they see—item by item—as belonging either to the province of Eros or Thanatos. Obviously, most of the news reports—accounts of bombings and bloodshed, stories meant to spike our levels of fear and paranoia—are direct communications from the kingdom of Thanatos, but so are most of the ads, targeting the consumers of blood-sugar monitors and arthritis remedies. Poor Eros makes a brief appearance only in the occasional car commercial, in the sexy sedan, obeying its invisible driver’s every command as it travels at dangerously high speeds through the desert landscape.

Some vestiges of a broader understanding of Eros and the erotic have managed, against all odds, to survive. One could still claim that the dinner scene in Henry Fielding’s Tom Jones is erotic in its depiction of gastronomy as foreplay. A restaurant critic might claim that the effect of the fish lightly kissed with a tomato-licorice foam is positively erotic, without confessing that he wants to have intercourse with the halibut on his plate. One can say that the warmth of the sun on the skin, on a cool autumn day, is erotic, again conjuring up the atmosphere of sex but not, specifically, the mechanics of it.

By contrast, pornography is all about the mechanics, minus the mystery and the metaphysics. Pornography has always been less about aesthetic content than about physiology. The Greek origin of the word (quite literally, “prostitute writing”) obviously implies a much narrower focus than a word derived from the god of passion and desire. Erotic literature or art can be judged by a wide range of criteria: Is it beautiful? Is it true? Does it reflect the viewer’s own experience of sex or love or pleasure? The requirements and standards for assessing pornography are simpler: Does it, or does it not, succeed in getting its audience hard?

At the Procuress’: The Courtesan, by Jan Vermeer, 1656. Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, Dresden, Germany.

As in the case of everything however remotely or directly related to sex, the most puritanical and hypocritically moralistic elements of our society (a group that, sadly, includes our lawmakers) have surrounded pornography with such an aura of evil and condemnation that, for many, it has become inextricably associated with sexual violence against women. (My own feeling, or hope, is that pornography does little to incite the would-be rapist; on the contrary, effective porn might prevent the potential attacker from making it out the door to commit his crime.) The linguistic consequence is that the pejorative connotation of the word “pornographic” has expanded to include the voyeuristic, the invasive, and any text or image that provides the reader or viewer with an inappropriate buzz of suspect curiosity or twisted gratification. I myself have employed “pornographic” to describe news photos of massacres and accident scenes, pictures in which the victims necessarily have no say about how they are viewed. In retrospect, I regret having settled for such a simultaneously sensational and approximate term. I can’t help wishing that I’d held out for something more precise and less loaded. Harking back to its origin, pornography has also become widely associated with exploitation just as it has become a loosely used synonym for anything creepy, displeasing, or distasteful. Like erotic, it too is used about food—in this case, food that is, in quantity and complication, excessive: “That platter of baby lamb’s tongues at the banquet was positively pornographic.”

By that definition, despite its being a sexual turn-off, the film of the two Bavarian girls dancing to Martin Luther King Jr. was pornographic in the extreme.

When I was a child, married couples on TV—Ozzie and Harriet, Desi and Lucy—slept in separate single beds. Now, any kid can tune into the afternoon soap operas and watch half-naked, gym-buffed lovers making theatrical love beneath, or even on top of, the sheets. If, as some claim, pornography is a drug, it may be that—given our increasingly sexualized culture—stronger and stronger doses of graphic sex are needed to deliver the requisite buzz, or, for that matter, to even qualify as pornography. While certain works of erotic art from the past (Indian miniatures, Japanese woodcuts) would still easily earn an R rating, others (James Joyce’s Ulysses, Édouard Manet’s Olympia) seem now—to extend the metaphor of porn as pharmaceutical—as mild as a baby aspirin. Given how our sense of the erotic and the pornographic has changed over the last half-century, it’s interesting to consider a work, Vladimir Nabokov’s Lolita, that was thought to be extremely pornographic when it first appeared, and to look at how it appears to us now in light of the changes that have since transpired in our culture.

In his essay, “On a Book Entitled Lolita,” written in 1956, shortly after the novel’s publication, Nabokov offers a characteristically incisive and useful description of pornographic fiction:

[I]n modern times the term “pornography” connotes mediocrity, commercialism, and certain strict rules of narration. Obscenity must be mated with banality because every kind of aesthetic enjoyment has to be replaced by simple sexual stimulation which demands the traditional word for direct action upon the patient…Thus, in pornographic novels, action has to be limited to the copulation of clichés. Style, structure, imagery should never distract the reader from his tepid lust. The novel must consist of an alternation of sexual scenes. The passages in between must be reduced to sutures of sense, logical bridges of the simplest design, brief expositions and explanations, which the reader will probably skip but must know they exist in order not to feel cheated…Moreover, the sexual scenes in the book must follow a crescendo line, with new variations, new combinations, new sexes, and a steady increase in the number of participants (in a Sade play they call the gardener in), and therefore the end of the book must be more replete with lewd lore than the first chapters.

It was similarly characteristic of Nabokov to want to define the terms of the conversation, then current, about his own novel— specifically about whether or not Lolita was pornographic. Doubtless there are learned societies devoted to the details of Lolita and Humbert Humbert’s sex life, academic conferences assembled to hear Lacanian readings of what the runaway couple did and didn’t do behind the closed doors of the wigwam motels where they found refuge during their epic cross-country journey. But as far as I know, the question of the novel’s status as pornography is not much talked about now, though I would imagine that the book is likely banned in those public libraries patrolled by vigilant parents who have discovered that books can be banned (without the fuss and bother of a formal process) by borrowing and not returning them until they’re no longer replaced.

It’s not only that we’ve learned better. The book is literature, and to talk about the pornographic content of literature is tantamount to identifying oneself as a lowbrow. In addition, we can be fairly sure the book’s actual sexual content would seem mild these days compared to what is “out there.” It probably wouldn’t even earn NC-17 status. On the other hand, its nominative subject matter (Humbert Humbert’s pedophilia) is fully as controversial as it was in the forties and fifties, perhaps even more so, since it is so often the first thing we think of when we see a priest’s cassock, a coach’s whistle, or a Boy Scout troop leader’s chestful of merit badges.

In any case, the fact is that most readers—or so I’d be willing to bet—tend not to remember the “dirty parts” in Lolita. For whatever reasons, the first tentative gropings and fumblings, and the scenes in which Humbert possesses his adored Lo, are not what lodge in our minds.

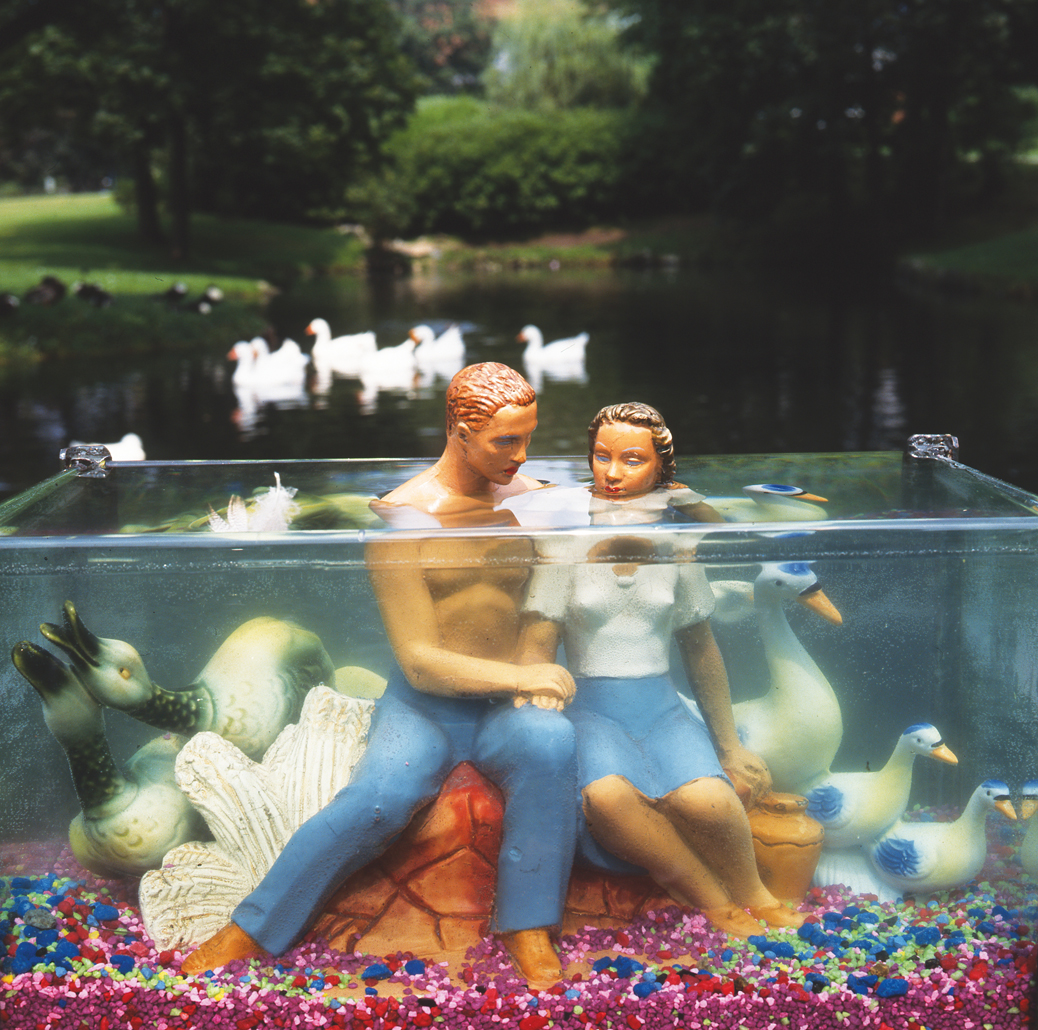

“Ducks and Lovers,” 2008. Photograph by Arthur Tress. © Arthur Tress, Courtesy ClampArt Gallery.

I had read the novel several times. I retained Humbert’s childhood love affairs, his meeting with Lolita, his courtship of her mother Charlotte Haze, and Lo and Humbert’s cross-country trips precipitated by Charlotte’s death. I remembered Lolita’s ditching Humbert for the mysterious Clare Quilty and the trailer-trash incarnation of his beloved that Humbert tracks down to the aptly named Coalmont, where he finds her pregnant and living in squalor with her husband. And I could hardly forget the chaotic and protracted scene in which Humbert murders Quilty, a passage which—when I was Lolita’s age, more or less—I heard read by Nabokov on the radio, at a time when I didn’t know what book it was from or who the author was, but I nonetheless somehow understood that it was extraordinary. Also having once participated in a marathon reading of Lolita, I recollected the chapter I was assigned to read aloud, the hilarious school-admission interview in which Humbert, who is of course sleeping with his pretend daughter, is lectured by the bluestocking, “progressive” principal who believes she has all the most liberal, even revolutionary, ideas about girls and sex and so forth.

I knew that the couple was having sex—there was Humbert’s hyperawareness of how many beds were in every motel room—but I simply couldn’t remember any scenes in which they did. When I mentioned this to a friend, he said, “Are you kidding? Check out the section, early in the book, in which Lo has her legs across Humbert’s lap.” During that scene, which I hadn’t recalled, Humbert contrives to sing a popular song as the pressure of Lo’s legs (she is munching on an apple) against his groin arouses him:

By this time I was in a state of excitement bordering on insanity, but I also had the cunning of the insane…Suspended on the brink of that voluptuous abyss (a nicety of physiological equipoise comparable to certain techniques in the arts) I kept repeating chance words after her—barmen, alarmin’, my charmin’, my carmen, ahmen, ahahamen—as one talking and laughing in his sleep while my happy hand crept up her sunny leg as far as the shadow of decency allowed…and because of her very perfunctory underthings, there seemed to be nothing to prevent my muscular thumb from reaching the hot hollow of her groin—just as you might tickle and caress a giggling child—just that—and: “Oh it’s nothing at all,” she cried with a sudden shrill note in her voice, and she wiggled, and squirmed, and threw her head back, and her teeth rested on her glistening underlip as she half turned away, and my moaning mouth, gentlemen of the jury, almost reached her bare neck, while I crushed out against her left buttock the last throb of the longest ecstasy man or monster has ever known.

Is the moment erotic? Obviously, the force of Eros is what inspires and rewards Humbert’s encounter with Lo. The scene at once celebrates and exemplifies all those aspects of Eros—energy, passion, vivacity, humor—that include and go beyond the merely sexual. Nabokov refers to the scenes near the start of his novel as “erotic,” passages that persuaded certain and subsequently disappointed readers “that this was going to be a lewd book.” But does it go beyond the erotic? Is it pornographic? Gentlemen of the jury, I’d argue that the passage is too cerebral, too humorous, too ironic, and above all, too giddily verbose to perform the work of pornography. The dazzle of language distracts us from the concentration that sexual excitement requires and provides. It’s rather like having one’s partner begin to prattle, in the midst of lovemaking, about the weather or the stock market or the undone household chores. It’s hard to imagine a reader whose sexual buzz could remain unaffected by phrases such as “the hidden tumor of an unspeakable passion” or “the corpuscles of Krause were entering the phase of frenzy.”

There is also the scene in which Humbert first has sex with Lo. Ever since the start of their journey in the aftermath of Charlotte Haze’s death, Humbert has been planning to drug Lolita with some sort of sleeping pill. But— as is so often the case—things turn out rather differently from what our hapless narrator has in mind: “I had thought that months, perhaps years, would elapse before I dared reveal myself to Dolores Haze, but by six she was wide awake, and by six fifteen we were technically lovers. I am going to tell you something very strange: it was she who seduced me.” Humbert continues, “My life was handled by little Lo in an energetic, matter-of-fact manner as if it were an insensate gadget unconnected with me…But really these are irrelevant matters; I am not concerned with so-called ‘sex’ at all. Anybody can imagine those elements of animality. A greater endeavor lures me on: to fix once for all the perilous magic of nymphets.”

If we limit our definition of pornography to that which leads more or less directly to sexual arousal, there are, hopefully, a limited number of readers for whom these scenes will function as pornography—who will feel a rush of desire in response to a heavily ironic account of a middle-aged sleazeball (however charming) attempting to drug and rape a child. I suspect the same about the subsequent passage in which Humbert fondles Lo while she is picking her nose and reading the comic pages, as well as the shorthand with which Nabokov later describes the illicit couple’s lovemaking: “Venus came and went.”

The Steadfast Philosopher, by Gerrit van Honthorst, c. 1620. Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, Austria.

Defending his novel against the charge that it was pornography, Nabokov focused on its form, on the ways in which the novel’s structure differs from that of the conventional pornographic narrative. Lolita does not merely “consist of an alternation of sexual scenes” or follow “a crescendo line,” always incorporating “new variations, new combinations, new sexes.” But just as important, clearly, is the question of content.

In making a case for Lolita as art—erotic certainly in its opening chapters and then increasingly less so as Humbert’s lust is increasingly transmuted into desperation and self-loathing—let’s return for a moment to the wider way in which pornography is currently defined: voyeuristic, exploitative, decadent. I remember using the word to describe the popular TV series To Catch a Predator, in which obviously ill sex offenders were lured, via Internet chat rooms, into confusing their fantasies with reality—that thirteen-year-old of their dreams wanted them! She was home alone, waiting for them, right now! Then they were exposed and busted by a suave anchorman, tackled, flung down, and handcuffed, usually on the front lawn of the house in which the sting had occurred.

It’s hard to understand who found this spectacle entertaining. But sadly, one can all too easily imagine audiences consciously or unconsciously turned on by the vice-cop-on-pervert wrestling matches and the romance of power and violence they represented. I’d prefer not to believe that I am living in a culture in which TV viewers got actual hard-ons watching the shaming and sadistic struggles that ended with the perp hog-tied with his face in the grass. But sexuality is a mystery, as individual as our fingerprints, so how can I know whether the satisfaction my fellow Americans took in these performances was punitively “moral,” or physiological, or both?

Among the qualities—beauty, intelligence, grace, complexity, facility of language, wit, among countless other literary virtues—that distinguishes Lolita as a work of art is the fact that it functions as the opposite of, and the antidote to, programs like To Catch a Predator. Lolita deepens our well of compassion and sympathy, whether we like it or not. The predator is caught, but first Nabokov’s novel charms and badgers, irritates and delights us into seeing the world through the eyes of the perp. That near miraculous feat reminds us of something else that is near miraculous—the fact that art coexists in the same world in which, in a studio somewhere in Bavaria, a cameraman shoots some footage of two hapless junkies—I forgot to mention the disturbing close-ups of the needle tracks on the women’s legs—gyrating to techno pop, and then someone adds on to the audio the sly joke that these white girls are Martin Luther King Jr.’s dream.

If Eros is the life force, then Lolita is—for all its ironic remove and tragic desperation—Eros between the covers: Humbert Humbert’s loopy, unpleasant, celebratory, obnoxious human voice erupting like a jack-in-the-box each time we open the book, even now, especially now, at this moment in our history when it so often appears that Thanatos has Eros pinned like those sex offenders on the front lawn.