One should either be a work of art, or wear a work of art.

—Oscar Wilde, 1894Between the Pinstripes

Cintra Wilson masters a disguise.

Washington, DC, is the center of the nation’s power; power is the narcotic that Washington’s most ambitious sociopaths crave, beyond fame or money. Since power is essentially defined by its enforcement, Washington is a city defined by war; the collective mood ring, if not its actual color palette, is always on Orange Alert. Since the closets of the nation’s capital naturally reflect the defense/security/intelligence industrial complexes that are the prime movers of its regional economy, residents of Washington, DC, tend to dress very defensively. Their overprotective office wear essentially serves as both camouflage and psychological body armor. Since intelligence is power in DC, DC fashion statements tend to be extremely conservative and deliberately boring. There is no content that can be read in a navy blue Brooks Brothers suit, save a certain tax bracket. It’s a symbolic and sartorial corpse.

Washington, DC, fashion statements read like blacked-out documents released under the Freedom of Information Act, in that they betray no relevant, timely, or interesting personal information whatsoever. DC fashion statements tend to be almost entirely redacted.

The business zone of America’s political power center includes the Pentagon and blocks of homogeneous office buildings in the suburbs of Maryland and Virginia. The whole area is surrounded, both physically and psychologically, by Interstate 495, the Capital Beltway—which I like to think of as a metaphorical belt, not unlike the rope worn about the waists of Hasidic gentlemen that symbolically separates the upper half of their bodies from the lower. The Beltway separates hearts from minds, reason from dialogue, men from women, and power from the wretched refuse and teeming hordes that compose most of the American citizenry.

In July 2005, Rolling Stone assigned me to the White House press corps for five weeks. It was a tense and divisive time. The second term of the Bush administration was kicking into third gear, Valerie Plame’s CIA cover had just been exposed, and this outrageous news cycle had just been deliberately derailed by the nomination of Justice John G. Roberts to the Supreme Court. There was a larger-than-usual helping of snappy young Republicans humming around the White House—young women with prematurely wide, matronly hips and undersized cheerleader features, dressed in A-line Lady Bird Johnson–style dresses, with tightly twisted hair knots and pinkly detailed Coach handbags. Guys in their twenties were proudly shorn into a round-headed military look, and wearing wraparound Oakley sunglasses, boxy dark suits, and the periwinkle blue shirts that were, that spring, the reigning uniform of the GOP camp (I nicknamed them “Blueshirts”). They seemed to share an abrasive, stinging kind of confrontational cleanliness, as if they had all just graduated from Brigham Young University with their virginity intact, and celebrated by being shaken and poured into the nation’s capital from an icy tumbler full of Pine-Sol, pumice, and the New Testament.

I was being thrown into Washington, DC, entirely ignorant of what I was about to be covering—so, to appear less out of my element, I nervously decided to arm myself by blowing a bunch of money (that I didn’t actually have) and investing in a proper pinstripe suit.

At some point in time, there must have been some patriarchal conspiracy—a back-room deal between the Freemasons, the Mafia, Italian wool manufacturers, and the Council on Foreign Relations—that has made it virtually impossible for a lady to find a commanding, off-the-rack pinstripe suit in a simple, well-tailored-yet-unslutty cut. I trolled the better department stores only to find suits for women that all seemed to be awkwardly cut in inferior fabrics, and/or larded with ruffles or ribbons or some other ghastly feminizing element that robbed the lines of simplicity. I was no more able to find skirt suits in the right gray flannel or three-season Italian cashmere than I was in worsted Kevlar or 80-grit sandpaper. I finally broke down—I had no option but to get down and dirty and have a suit custom made—but it didn’t come without a fight. The tailor, a Korean man, informed me that even the suiting material I’d managed to buy on the Internet and bring to him—a lightweight indigo wool with faint white pinstripes one inch apart—was ordinarily reserved exclusively for menswear. He told me that female suits are far deadlier than the male: men, apparently, are easier shapes to drape in pinstripes. The creation of a bespoke women’s two-piece requires the highest-level black belt skills, in terms of the tailoring arts. I declined to accept this verdict as an incontestable law of nature, and bared my teeth over interminable delays in delivery—but ultimately, I got the suit in time. I believe the poor man truly suffered for it.

Nothing feels quite so importantly badass as your first lethal pinstripe suit. Like a first motorcycle jacket, invest in the best one you can buy without ruining your credit or going to jail, and then submit—let the transformative effect of it swallow you whole. That is how you fall through the looking glass into weird new phases of adventure.

One pair of black Prada slingbacks (bought for approximately the same price as the whole damned suit), a nerdy pair of glasses, and a necklace and earrings made of ten-millimeter “fuck-you” pearls later (eBay), I felt sufficiently camouflaged to hang out with my journalistic superiors in the James S. Brady Briefing Room.

But even my proud and hard-won pinstripe costume could not prepare me for sitting in the same room as Fox News’ Carl Cameron.

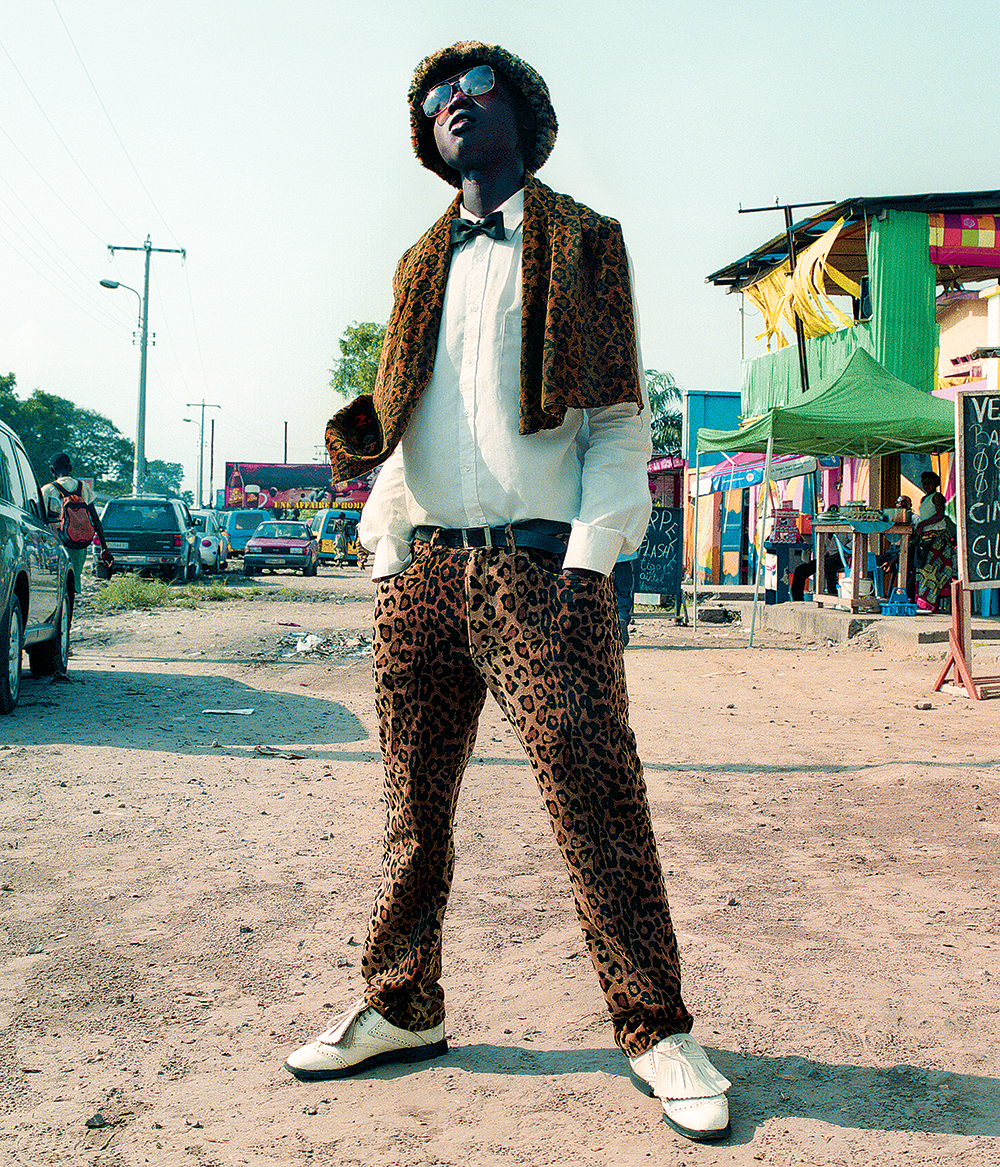

Kinshasa posse #2, from the series Sapeur, by Jackie Nickerson, 2011. © Jackie Nickerson. Courtesy the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.

Other reporters might show up for briefings looking deadline sleep-deprived, windblown, or slightly hungover—that Woodward-and-Bernstein-as-played-by-Redford-and-Hoffman look that says, I am carrying the fire of such important, time-sensitive information, so I obviously can’t be expected to button all the buttons on my shirt, and this was the only tie I happened to have wadded up in my glove compartment. Carl Cameron, in contrast, always looked as freshly clipped, manicured, and clear-eyed as if he’d just slept eight hours at the rectory, drunk a warm cup of nourishing electrolyte broth, and been ritually bathed, powdered, and tweezed by a team of executive choirboys. It was a level of ultraconservative, hyperconformist supergrooming I have never witnessed before or since—a radically professional, germ-free appearance that I could only picture being equaled by an astronaut, or a baby in an intensive-care unit. The effect is uncanny—Carl Cameron’s personal presentation conveys a total self-abnegation and control-freakiness that could conquer any obstacle to professionalism, from lint to sorcery.

If your goal is to work in or around the government, the unwritten rule, as it is in most professions, is to dress for the job you want, as opposed to the job you already have. In Washington, DC, this hierarchical imitation-as-flattery-as-day-look has created a negative fashion feedback loop. The higher DC residents ascend professionally, the more deeply and successfully they submit their closets to this uniform superconformity. Type-A go-getters in the nation’s capital must look dissimilar from the whole, but somehow magically more so. Like Carl Cameron, they must stand out just enough from an otherwise identical crowd by being the cleanest, most twinkling headstone at Arlington.

After my White House stint, I ended up spending nearly five years regularly loitering around Washington, DC, for one reason or another. I was insatiably curious about the metabolism of the defense industry, having caught what the locals call “Potomac fever.”

Airtight fashion laws are a natural extrusion of Washington’s locked-down, security-addicted collective mindset. Proper clothing is an initiatory wall of fire that everyone has to pass through; the “right clothes” are one of the prices of admission. Democracy may or may not end at the footsteps of the capital…but it definitely ends by the time you get to the coat check.

To achieve harmony in bad taste is the height of elegance.

—Jean Genet, 1949One of the best anecdotal examples of this is when Google cofounder Sergey Brin arrived on Capitol Hill one day in 2006, believing his worldwide clout would be a sufficient door-opener for him to casually drop in and meet members of Congress. “The visit, which was reported in the Washington Post, was hurried, and, in what was regarded by some as a snub, Brin failed to see some key people,” Ken Auletta wrote in The New Yorker. “It probably didn’t help that his outfit that day included a dark T-shirt, jeans, and silver mesh sneakers.” The blog The 463: Inside Tech Policy corroborated Brin’s fashion faux pas: “We still hear from Hill staffers about so-and-so big-name tech CEO who dared wear jeans (with a sport jacket and loafers) in their office back in the 1.0 age, and how their boss quietly fixated on the breach of etiquette.”

Such is the inviolable nature of DC’s fashion totalitarianism.

Capitol Hill didn’t care that Sergey Brin was potentially the biggest asset in the Western world for an upcoming cyberwar with China. Anyone who has managed to rise to a prominent position in the realpolitik machinery of the free world needs to see the stripes on your necktie first so they know you’re safe to play with. It’s a military town, and Brin’s way-too-casual-Friday look was perceived as a severe breach of protocol. The attitude to this buffoonish invasion, loosely articulated: Oh, so—you must be Mr. Special Internet Genius? Well, perhaps when you’re swinging on the big tire in your California jungle gym you can wear flip-flops and a Levi’s loincloth. “Thinking out of the box” might be a swell advantage over there in Silicon Valley or Asperger’s Island or whatever you kids call it, but in Washington, DC, by God, our sandbox is called the Middle East, and we have these things called security clearances, which mean that we are the only real grown-ups on earth who know the horrible truth. And we’ve got news for you, Captain Imagination: there is no “out of the box.” Anywhere. You’re always in the box. The more you think you exist outside of the box only shows how tragically ignorant you are of how deep the box is, and how inescapably in the box you really are. Enjoy your plane trip back to your own personal fairyland, where there’s cups of crayons in the lunchroom so you can be creative on your place mat. Now if you’ll excuse me, I’ve got some death to deal out.

Cintra Wilson

From Fear and Clothing. Born in Chico, California, Wilson wrote the Critical Shopper column for the New York Times from 2007 to 2011. “Expensive food writing and expensive clothing writing are fantasy pieces that aren’t realistic,” Wilson said in 2011. “There’s a very small percentage of people who live on the Upper East Side, who can buy these meals and clothes and shoes.”