Sir,

I have made inquiries on the subject of the negro boy you have brought, and find that the laws of France give him freedom if he claims it, and that it will be difficult, if not impossible, to interrupt the course of the law. Nevertheless I have known an instance where a person bringing in a slave, and saying nothing about it, has not been disturbed in his possession. I think it will be easier in your case to pursue the same plan, as the boy is so young that it is not probable he will think of claiming freedom. This plan is the more advisable, as an unsuccessful attempt to procure a dispensation from the law might produce orders which otherwise would not be thought of. Nevertheless should you find that you shall lose the possession of the boy unless protected in it, if you will be so good as to inform me of the facts, I will try whether a dispensation can be obtained. I would rather avoid asking this if you can, by any means, keep the boy without it. I have the honor to be with sentiments of much respect, sir, your most obedient humble servant.

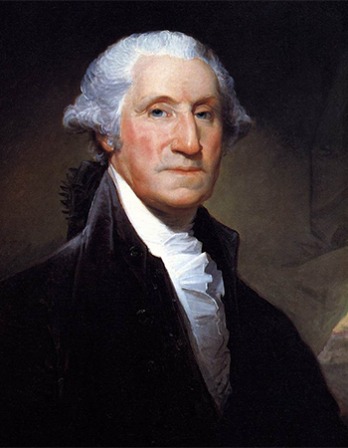

From a letter to Paul Bentalou. It is believed that the “person” to whom Jefferson referred in this letter was himself, having brought his slave James Hemings to Paris. James and his sister Sally were half-siblings of Jefferson’s late wife, Martha; their father, John Wayles, had, upon his death, willed the Hemings family and over 120 other slaves to the Jeffersons. Serving as minister to France from 1785 to 1789, Jefferson read the new Constitution while abroad, noting, “There are very good articles in it—and very bad. I do not know which preponderate.”

Back to Issue