This is an indictment in three counts. The first charges a conspiracy to violate the Espionage Act of June 15, 1917, by causing and attempting to cause insubordination, etc., in the military and naval forces of the United States, and to obstruct the recruiting and enlistment service of the United States, when the United States was at war with the German Empire, to wit, that the defendants willfully conspired to have printed and circulated to men who had been called and accepted for military service under the act of May 18, 1917, a document set forth and alleged to be calculated to cause such insubordination and obstruction.

The document in question, upon its first printed side, recited the first section of the Thirteenth Amendment, said that the idea embodied in it was violated by the Conscription Act, and that a conscript is little better than a convict. In impassioned language, it intimated that conscription was despotism in its worst form, and a monstrous wrong against humanity in the interest of Wall Street’s chosen few. It said, “Do not submit to intimidation,” but in form, at least, confined itself to peaceful measures such as a petition for the repeal of the act.

The other and later printed side of the sheet was headed “Assert Your Rights.” It stated reasons for alleging that anyone violated the Constitution when he refused to recognize “your right to assert your opposition to the draft,” and went on: “If you do not assert and support your rights, you are helping to deny or disparage rights which it is the solemn duty of all citizens and residents of the United States to retain.” It described the arguments on the other side as coming from cunning politicians and a mercenary capitalist press, and even silent consent to the conscription law as helping to support an infamous conspiracy. It denied the power to send our citizens away to foreign shores to shoot up the people of other lands, and added that words could not express the condemnation such cold-blooded ruthlessness deserves, etc., etc., winding up, “You must do your share to maintain, support, and uphold the rights of the people of this country.” Of course, the document would not have been sent unless it had been intended to have some effect, and we do not see what effect it could be expected to have upon persons subject to the draft except to influence them to obstruct the carrying of it out. The defendants do not deny that the jury might find against them on this point.

We admit that, in many places and in ordinary times, the defendants, in saying all that was said in the circular, would have been within their constitutional rights. But the character of every act depends upon the circumstances in which it is done. The most stringent protection of free speech would not protect a man in falsely shouting fire in a theater and causing a panic. It does not even protect a man from an injunction against uttering words that may have all the effect of force. The question in every case is whether the words used are used in such circumstances and are of such a nature as to create a clear and present danger that they will bring about the substantive evils that Congress has a right to prevent. It is a question of proximity and degree. When a nation is at war, many things that might be said in time of peace are such a hindrance to its effort that their utterance will not be endured so long as men fight, and that no court could regard them as protected by any constitutional right.

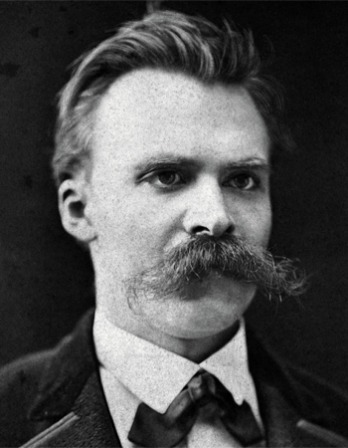

From Schenck v. United States. This decision upholding the conviction of Charles Schenck established the Supreme Court’s “clear and present danger” test, which limited the First Amendment’s protection of free speech. The doctrine was replaced in 1969 with the “imminent lawless action” test, holding that speech can be limited if it is likely to inspire unlawful activity before such activity can be prevented. Theodore Roosevelt appointed Holmes to the court in 1902 but came to regret his decision when Holmes advised it against enforcing the Sherman Antitrust Act in a monopoly case. “Out of a banana I could carve a firmer backbone,” Roosevelt complained.

Back to Issue