Do not boast about tomorrow, for you do not know what a day may bring.

—Book of Proverbs, 150 BCQuack Prophet

The prophecies of Nostradamus were cryptic and garbled—but they also let us see what we wanted to see.

By Colin Dickey

Solar eclipse, by Carleton Watkins, 1889. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, digital image courtesy of the Getty’s Open Content Program.

Soothsayers have been around as long as recorded history, probably longer—after all, knowing what’s to come has always been accorded more value than knowing what’s already happened. Whether Isaiah shouting from the mountaintop or Jim Cramer shouting from the television screen, there has always been power and notoriety to be gained from prognostication. But considering that most (if not all) of these seers—whatever market expertise or God-given insight they might claim for themselves—are just shooting in the dark, it’s not altogether clear what makes a good prophet. Showmanship and some lucky guesses, to be sure, but beyond that? This is the question that surrounds the strange and enduring popularity of one of the unlikeliest prophets: an ex-doctor from southern France named Nostradamus.

His name is almost a byword for cataclysm, trotted out over the centuries in the wake of major disasters as evidence that long ago someone had figured out they had been foreordained. Such was the case in the aftermath of September 11, for instance, when Nostradamus most recently reappeared in the spotlight. Today, venture into any bookstore’s occult section, and you’re bound to find multiple translations of The Prophecies, his best-known work, alongside books hotly debating its significance and validity. Or turn on the History Channel, and you might catch repeats of The Nostradamus Effect, a show that explored apocalyptic prophecies throughout history, with episodes bearing titles like “The Third Anti-Christ?” and “Armageddon Battle Plan.” His name and work have permeated our experience of doom and destruction, but the man himself is almost a cipher. Getting any kind of reliable understanding or impression of him takes some work.

Before you even begin, forget the Internet. A Google search of his name would leave you mired in hordes of conspiracy theorists, New Age peddlers, devotees who give him the cloying nickname “Nosty” and credulously recycle the same badly translated lines and outright inventions that people have always cited as “proof” of his foresight. You’ll find apocryphal prophecies, such as the one which warns that “two steel birds will fall from the sky on the Metropolis,” or logical contortionists like Nostradamus “expert” and self-styled prophet John Hogue, who contends that the prophecy beginning “When 1999 is seven months over” can be made a reference to 9/11 if one only reverses “1999” to “9-11-1,” and translates the French sept as “September,” not “seven.” There are literally millions of web pages like this, and the man himself—Michel de Nostredame—is scarcely evident behind all this noise.

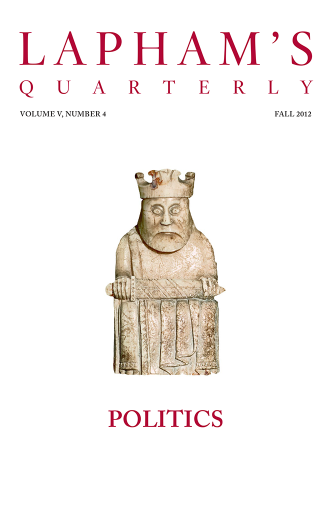

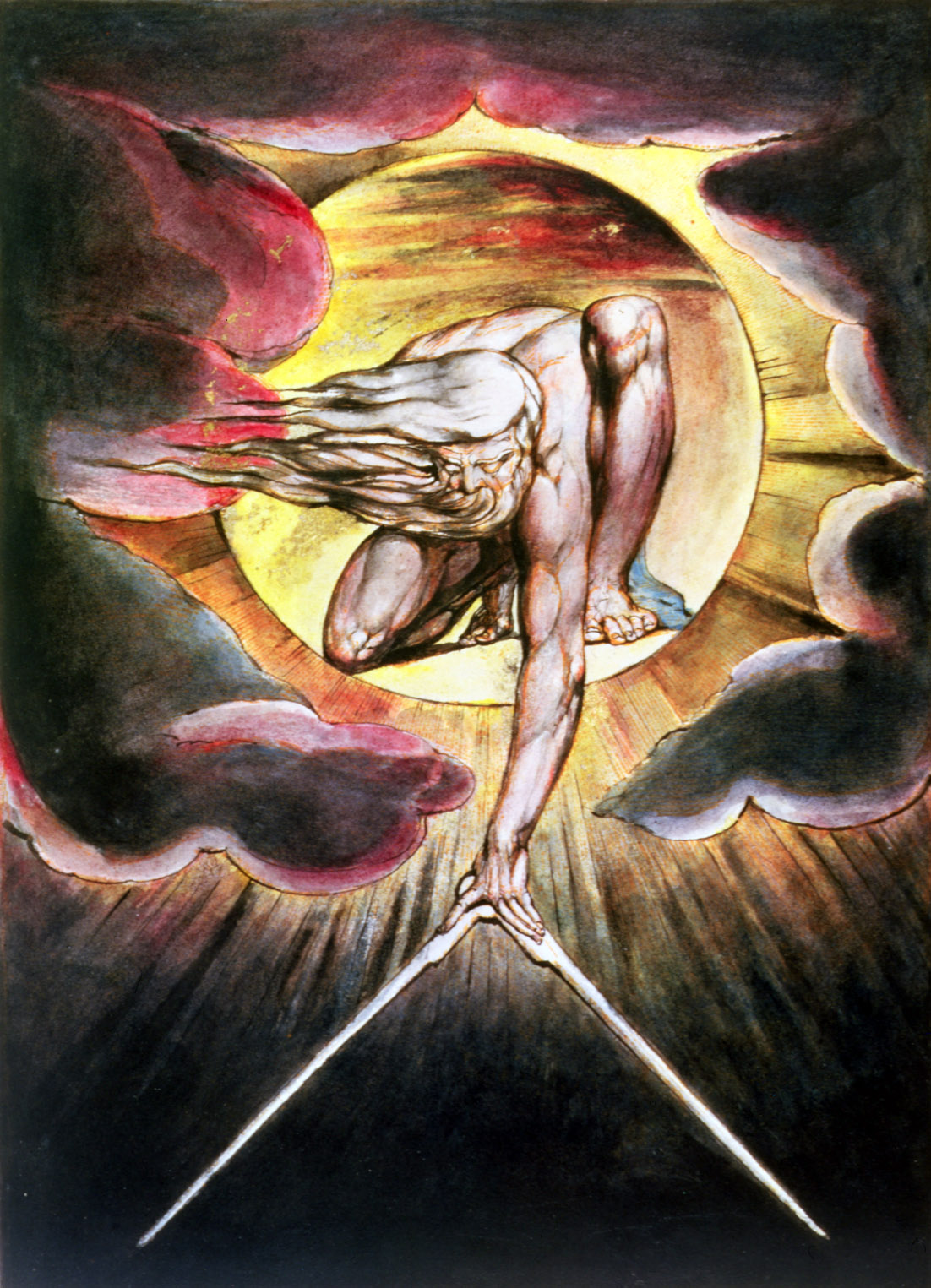

The Ancient of Days, frontispiece for Europe a Prophecy, both by William Blake, 1794. The Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge, United Kingdom.

The authoritative sources aren’t much better, unfortunately. In its entry for Nostradamus, the current edition of the Encyclopedia Britannica contains at least half a dozen basic factual errors. It gets known dates wrong: the years in which he began his medical practice, moved to the town of Salon, and began publishing The Prophecies, which it mistakenly calls Centuries. It also claims his books were banned by the Roman Catholic Church, which they never were.

He would have wanted it this way. His business was in secrets, and he spent much of his life building a sense of mystery around himself and his writings. He purported to have all the answers but claimed that “the danger of the times” required that “Such secrets should not be bared except in enigmatic sentences.” Dwelling in what he called “cloudy obscurity,” he constantly courted controversy and always had as many detractors as believers. “A certain brainless and lunatic idiot, who is shouting nonsense and publishing his prognostications and fantasies on the streets,” ran 1558’s First Invective of the Lord Hercules the Frenchman Against Monstradamus. That same year, the astrologer Laurent Videl, in his Declaration of the Abuses, Ignorances, and Seditions of Michel Nostradamus, crowed that “if I wanted to recite all the ignorances, errors, and idiocies that you have been putting in your works for the last four or five years, it would need a pretty big book.” This anonymous Latin epigram from the same time perhaps sums him up most succinctly: “Nostra damus cum falsa damus, nam fallere nostrum est: / Et cum falsa damus, nil nisi nostra damus.” “We give our own when we give the false, for it is ours to be false. And when we give the false, we give nothing but our own.” To look at Nostradamus is to give one’s own, and to see what you want to see.

He was born on December 14, 1503, in St. Remy-de-Provence, as Michel de Nostradame. His paternal grandfather had been Jewish but converted to Catholicism and changed his name from Guy Venguessonne to Gassonet, perhaps to eliminate any suggestion of the Hebrew “Ven.” Nostradamus later played up the mystique of his Jewish heritage when he boasted that his “natural instinct” for prophecy had been “inherited from my forebears.” Gassonet later changed his name again to Pierre de Sainte-Marie in 1455, and then once more to Pierre de Nostradame. Michel would later Latinize his surname to Nostradamus in 1550, when he started writing, the alteration then a fashionable way to suggest erudition.

When he was still Nostradame, however, he tried to make his name first through more traditional means, spending his early years attempting to combat the Black Death, which ravaged Europe in the fourteenth century, and continued to flare up throughout the continent in brief, deadly bursts. He had early on developed an interest in medicine and enrolled as a teenager in the University of Avignon in 1519. A year later, though, the town was stricken by plague, and the university closed down, advising its students to flee to the countryside. Unmoored, Nostradamus became a traveling apothecary, roaming throughout France, Italy, and Spain. He spent eight years, in his words, occupied with “the study of natural remedies across various lands and countries, constantly on the move to hear and find out the source and origins of plants and other natural remedies involved in the purposes of the healing art.” He returned to school again in 1529, this time at Montpellier, but this too would only last a year—he was quickly expelled after the university learned, in the registrar’s words, that he was an “apothecary and a quack.” Apothecaries were reviled throughout Europe as little more than charlatans: a London editorial once described the “mere apothecary” as a “creature that requires little brains. There is no branch or business in which a man requires less money to set him up than this very profitable trade: ten or twenty pounds, judiciously applied, will buy gallipots and counters and as many drugs to fill them with as might poison the whole island.”

A pharmacist again, by 1531 Nostradamus had settled in Agen, where he married a woman named Henriette d’Encausse and fathered two children. During these years he began to perfect his own plague prevention: rose lozenges. He boiled down cypress shavings, iris root, cloves, sweet calamus, and aloe and then tossed in “three or four hundred infolded roses, fresh and perfect clean, and gathered before dewfall.” This seemingly arbitrary prophylactic followed the generally accepted notion that plague was spread by “miasma,” bad air, and that the best way to protect against it was through sweet scents and fragrances. (The iconic beak of the plague doctor’s mask was actually functional, filled with herbs and flower petals to keep the air pure.) Then, in 1534, disaster struck: both Nostradamus’ wife and his two children died that year, from plague.

The tragedy itself must have been hard enough to bear; worse, the apothecary had made his career on the claim that he could cure the Black Death. Perhaps to prove that his labors thus far weren’t a waste, he threw himself into his work. He spent the next twelve years apprenticing himself to doctors and apothecaries throughout France, and was finally given a chance at more regular employment in 1546, when he was hired by the city of Aix-en-Provence to treat a fast-moving outbreak of plague. His later description of those events remains fairly chilling: the plague killed such “an extraordinary number of ordinary, eating, drinking people of all ages,” he wrote, that “The churchyards were so full of dead bodies that nobody knew of any further consecrated ground in which to bury them.” He described the plague as so swift that “Even with gold and silver in their hands, people often died for want of a glass of water,” so terrifying that “Fathers took no care of their sons, and many abandoned their wives and children as soon as they realized that they had been infected.”

Some of Nostradamus’ best writing is here, as a frontline reporter of a disaster so total that human civilization seemed to collapse utterly. “Among the most admirable things I saw,” he recalled, “was a woman who, even while I was paying a visit on her and calling to her through the window, replied to what I was saying—still through the window—while sewing herself unaided into her own shroud, starting with the feet. And when the alarbes arrived (which is what we in Provence call those who take the plague victims away and bury them) and went into this woman’s house, they found her dead, lying in the middle of the house with her sewing half-finished.”

The Gulf Stream, by Winslow Homer, 1899. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Catharine Lorillard Wolfe Collection, Wolfe Fund, 1906.

After nine months the plague followed its natural course and died out, but Nostradamus could claim success in treating it, for no other reason than he was still alive. This “triumph” at Aix-en-Provence led to offers of similar jobs the next year in Lyon and Salon. While in the latter, he met a wealthy widow, Anne Ponsarde, whom he married in November 1547. But even though he was now respected as a successful plague doctor, he perhaps realized it wouldn’t work as a long-term career. He left France altogether and toured Italy for the next two years. By the time he returned, he had begun to imagine a new profession for himself.

In 1550 Nostradamus published his first almanac, switching his focus from the plague to Europe’s other source of constant anxiety and speculation: the weather. That year saw the encroachment of glaciers into Europe in what would become known as the Little Ice Age, a period of cooling that would have calamitous effects on agriculture. With crops failing due to persistent frosts, farmers turned for guidance to the plethora of cheap, disposable almanacs which were then flooding the market. And while these offered useful astronomical data such as cycles of the moon, they also generally followed the traditional Ptolemaic belief that weather was affected by the stars and planets, and had thus evolved to include astrology as well. Forecasts like “hail, thunder” and “disturbed air/rough winds” ran alongside predictions like “fire from the sky searing ships” and “some noble shall be born!”

Though Nostradamus was never a properly trained astrologist, and repeatedly made elementary mistakes, it was in this field that after a few years he began to distinguish himself. His earliest predictions had been ambiguous, forgettable: “Throughout Gaul there shall be certain uprisings which shall be appeased by stern counsel,” or, “The bodies aloft threaten great bloodshed at the two extremities of Europe, in the east and in the west, and in the center shall be in most uncertain fear.” They were generic, even in their foreboding doom, and they generally reflect a writer unwilling to take a risk or be proven wrong. Gradually, though, he moved from the vague to the obtuse; in his 1553 almanac he warned that a “new Themistocles shall inflict a great and unhappy vexation on his people,” and that “The great Hannibal on the matter is in danger of failing.” While on the surface the change might seem slight, this move from indefinite nouns such as “certain uprisings” to specific, albeit allegorical, figures began to make his prophecies look less like random guesses and more like solid facts that just hadn’t yet been decoded. His repertoire came to include untranslated Latin from obscure poetry and histories (usually in the form of inappropriate and distorted citations), malapropisms and non sequiturs, abstractions and metaphors—a mélange of nonsense that nonetheless had the paradoxical effect of sounding highly specific.

Then in 1555, in addition to his regular almanac, Nostradamus published the first edition of The Prophecies, organized (roughly) into groups of one hundred quatrains, each called “Centuries.” Not restricted to a single year, The Prophecies didn’t have an expiration date, and it was in them that he honed his deliberately obtuse style:

Those well at ease will suddenly be put down;

By three brothers the world put in trouble.

Enemies will seize a maritime city,

Hunger, fire, blood, plague, and all evils doubled.

He will come from Mont Gaussier and Aventine,

Who will warn the army through the hole:

Between two rocks the booty will be taken,

The fame of Sextus’ mausoleum to fail.

It’s difficult, when reading these, not to try to make sense of them. Whether it’s the Dead Sea Scrolls or Finnegan’s Wake, there’s a long literary history of taking the garbled and the fragmented and looking for lucid meaning beneath. The science writer and professional skeptic Michael Shermer has gone so far as to argue that we’re hard-wired, from an evolutionary perspective, to look for such hidden meanings. “From sensory data flowing in through the senses the brain naturally begins to look for and find patterns, and then infuses those patterns with meaning,” Shermer writes. “We can’t help it. Our brains evolved to connect the dots of our world.” By adjusting the signal-to-noise ratio, Nostradamus introduced enough static into his Prophecies that they could be all things to all readers, poetic Rorschach blots of detail and blur.

The Prophecies didn’t sell well at first, however, but by the time he released the first edition, his almanacs were bringing him commercial success and fame: in a few short years Nostradamus had become the name in weather prophecy, so much so that others were rushing knockoffs into print to capitalize on his name. As the Vicar of Provins wrote at the time, “No other astrologer has produced an almanac having renown or currency throughout the kingdom of France other than by doing so under the name of the said Nostradamus.” Certainly much of his success lay in his increasingly apocalyptic tone, with promises of a “world in trouble” and “all evils doubled”—after years of futile struggling against the plague, he seemed to have decided that it was far easier to narrate the apocalypse than try to fight it.

It was his almanac for 1555 that was received enthusiastically by Alexandre de la Tourette, President of the Masters General of the Ministers of France and an amateur alchemist. De la Tourette sent around several copies, and in July of that year, Nostradamus was summoned by the queen of France, Catherine de Medici.

Belshazzar’s Feast, by Rembrandt van Rijn, c. 1635. National Gallery, London.

The Italian-born queen of Henry II, Catherine’s superstitions were well-known throughout France; she usually had astrologers attending her or employed on her payroll, even though they were often wrong. She was not alone in her credulity, but credulity in one so powerful attracted its fair share of hucksters and charlatans—to the point where her third son Henry would later exclaim, exasperated, that he was tired of seeing his mother “cheated by false magicians who got a great deal of money out of her and didn’t do anything.” Nostradamus now joined this long list of seers, and dutifully visited to read the fortune of Catherine and Henry’s children, for which he was paid a modest fee of one hundred and thirty crowns (one hundred of which, he complained bitterly to a friend, was spent on the arduous trip to Paris itself).

At the time, his contemporaries were still more interested in the coming year than 1999 or 3797. But then came the unexpected. During a festival on June 30, 1559, Henry II took part in a jousting match, during which a freak accident occurred: his opponent, Gabriel Montgomery, broke his lance on Henry’s shield, and a sliver of the wood shot up under the king’s helmet and lodged above his eye in his brain. Henry bore it bravely, but lingered in agony for ten days before he died.

Now many at court, mourning and looking for answers, turned to the thirty-fifth quatrain in the first Century of the Prophecies:

The young lion will overcome the old

On the field of battle in single combat:

He put out his eyes in a cage of gold:

Two fleets one, then to die a cruel death.

Skeptics could protest that Montgomery may have been only six years younger than Henry—and not exactly “young”—or that Henry’s helmet was probably not made out of gold, or that the splinter in his brain did not actually enter his eye, or that no “fleets” of any kind were involved. But none of those arguments, then or now, mattered to those who—most notably Catherine herself—were convinced that Nostradamus had foreseen the king’s freakish demise.

In the wake of her husband’s death, Catherine began regularly consulting Nostradamus and his prophecies. She brought up his predictions in discussions with foreign ambassadors, and in 1564 brought her son, King Charles IX, to Salon to have his fortune read by the seer, who told the fourteen-year-old ruler he’d be “A great man in war, second to none in piety.”

His prophecies were not always so pandering. He told Catherine that all four of her sons would live to be king, which sounds good until one realizes that this means the first three were headed for early deaths. He went on to predict that one day her entire line would be extinct, the seeming accuracy of the forecast providing cold comfort when her favorite daughter Elizabeth died in childbirth a few years later. Indeed, when one tallies up Nostradamus’ predictions, he seems to have been most accurate when predicting calamity for his greatest patron. But Catherine’s life was always going to be one of constant violence and sudden destruction. If his quatrains could not stop all of this, at least she could take comfort in knowing that there was some larger order governing this chaos. Be it in the stars or in God, at least the deaths of her husband and children weren’t entirely arbitrary.

Nostradamus was a voice for his times. He spoke of wars, famines, dynasties falling, and the world ending, and after his death in 1566 from dropsy, his writings would continue to reappear in times of similar calamity. Theophilus de Garencières, his first English translator, published The Prophecies in London in 1672, just six years after much of the city had been destroyed, first by plague and then by fire. In those tumultuous times in England, Nostradamus’ work found a new life in assuaging Britons’ anxieties: when Charles II failed to produce a legitimate heir, a pamphlet appeared falsely claiming that Nostradamus had predicted the king would soon sire a son from his own body.

It is in times of great national uncertainty that editions and translations of his work are most numerous: England in the seventeenth century, and France again at the end of the eighteenth, when Nostradamus was touted as having already predicted the French Revolution. As with his predictions for Catherine de Medici, it didn’t matter that he often seemed to suggest that things were going to get much worse—what mattered was the sense that someone had discovered the order in the madness, and Nostradamus best played the part of a strangely reassuring voice in a time of doom. (Though this reassurance didn’t keep a legion of Revolutionary troops stationed in Salon from breaking open his casket and desecrating his remains—the prophet being one more affront to the new atheist state.)

I don’t try to describe the future. I try to prevent it.

—Ray Bradbury, 1992When Napoleon came to power a few years later, the prophet was once again consulted, and commentators turned to quatrain VIII.1, which begins, “Pau, Nay, Loron more fire than blood shall be”—rearranging the names of those three towns in southwest France into Roy Napaulon. General Bonaparte thus became the first “Antichrist” in Nostradamus’ Prophecies, to be followed, over a hundred years later, by the second, “Hister,” an archaic name for the Danube River that was frequently and torturously deciphered as the vaguely similar-sounding Hitler, who was born near the Danube.

In 1921, a short book on Nostradamus appeared, published by one “C. Loog,” a postal worker from Berlin. It contained an interpretation of quatrain III.57 (“Seven times you will see the Britannic nation change,/Steeped in blood in two hundred and ninety years:/Free not at all, by German support./Aries doubts its Bastarnian pole.”), which inexplicably counted the 290 years from the beheading of Charles I in 1649 and translated “Franche” as “French,” not “free.” It also took “Bastarnian” as a reference to the Ukraine and Southern Poland, because, as Loog explained it, Bastarnians were a Germanic tribe who had once occupied that region. Add all this up, and you get some sort of bloodshed involving Britain, France, Germany, and Poland, happening sometime in 1939. Loog’s interpretation was picked up by Dr. H.H. Kritzinger in his Mysteries of the Sun and Soul, published a year later, and still in print by September 1939 when Hitler invaded Poland. A few weeks later, Magda Goebbels came across the passage in Kritzinger’s book and rushed to share the good news with her husband: the Third Reich’s triumph was preordained.

Throughout that fall, Josef Goebbels’ Ministry of Propaganda repeatedly discussed ways to use Nostradamus’ prophecies for good effect, even going so far as to summon Kritzinger that December. As the doctor later recalled, Goebbels repeatedly asked, “Have you got anything else on the same lines?” as if, Kritzinger put it, “I could shake one interesting prediction after another about Great Britain and the war out of my sleeve.” Unable or unwilling to produce what Goebbels wanted, Kritzinger instead suggested an astrologist and occultist named Karl Ernst Krafft, who in 1940 produced a pamphlet for Goebbels under the pseudonym “Norab,” entitled What Will Happen in the Near Future? The pamphlet was printed in over half a dozen languages, including English, specifically to be disseminated in foreign nations as proof of the Nazi’s imminent victory. Krafft’s interpretations of Nostradamus are often tortured, offering “undeniable proof” that within the British Isles “such horrible tumult” would break out that the UK would descend into Civil War.

But Krafft was not the only one claiming Nostradamus was on his country’s side. Pitting himself against Krafft was an occultist living in London, Louis de Wohl, who set out to combat Goebbels’ astrological warfare with some prophecy of his own. De Wohl produced a German-language book, Nostradamus Predicts the Course of the War, which claimed to be based on a secret Nostradamus manuscript recently discovered in Regensburg. De Wohl was thus able to manufacture his own quatrains that could refute Krafft’s: “Hister [Hitler] who carried off more victories in his warlike fight than was good for him: six men will murder him in the night. Naked, taken unawares without his armor, he succumbs.” De Wohl was shameless in his falsifications, but as the Vicar of Provins could have told you, this false attribution of prophecy to Nostradamus was nothing new. Meanwhile, Hollywood also got in on the act; after the United States entered the war, MGM began producing a series of short morale-boosting films, the first of which was titled Nostradamus Says So.

This war of prophecy was not without its own casualties: when the Nazi party leader Rudolf Hess fled from Germany to Scotland in 1941 to attempt in secret to make peace with the British, his defection was blamed on the undue influences of occultists, and Krafft was made the fall guy—arrested and sent to Buchenwald, he died along the way from Typhus.

In the past ten years Nostradamus’ popularity has once again flared, and his quatrains are being trotted out to suggest that he foresaw the attacks of September 11 and other global events. In particular, the believers have been working to puzzle out this quatrain:

Mabus then soon will die; there will come

Of man and beast a horrible defeat.

Then suddenly one will see vengeance,

Hundred, hand, thirst, hunger, when the comet runs.

If Roy Napaulon was the first harbinger of the Apocalypse, and Hister the second, then Mabus, Nostradamians agree, is the third, and they’ve been working to puzzle out who that might be. Suspects range from Mahmoud Abbas, to George W. “Mad” Bush. With the 2008 election Obama, Barack, of the US became a popular candidate (or, if you prefer, Michelle and Barack, US). As the guessing games continue endlessly on the Internet, one feels for the otherwise unremarkable Secretary of the Navy, Ray Mabus, since a Google search of his name helpfully suggests that he is, in fact, the Antichrist.

The same year of Obama’s election, researchers Jennifer Whitson and Adam Galinsky published a study on “illusory pattern perception,” in which subjects were shown recognizable figures blurred by a slight level of visual static, along with random static with no hidden images. The ones who claimed they saw patterns in the random static were people who also felt a great deal of loss of control in their lives, suggesting to Whitson and Galinsky that “When individuals are unable to gain a sense of control objectively, they will try to gain it perceptually.” The more out of control we see events around us, the more willingly—and eagerly—we’ll see patterns that may or may not exist, hunting for a sense of meaning guiding events.

Their study suggests the true significance of Nostradamus lies less in the future than in the present. After all, as detractors have pointed out, the Prophecies have never been used to predict the future; they are always cited after the fact as evidence of Nostradamus’ infallible accuracy. The legend of Nostradamus persists not because we want to understand what’s ahead, but because we want to believe—desperately—that some divinable order lies behind all the chaos.