Drunkenness is the very sepulcher / Of man’s wit and his discretion.

—Geoffrey Chaucer, 1390Last Testaments

What do artists and writers do when they are faced with the imminence of death? Francine Prose reviews the final works of historian Tony Judt.

By Francine Prose

Evening Landscape with Two Men, by Caspar David Friedrich, c. 1830-1835. State Hermitage Museum, Saint Petersburg.

A friend once announced to a dinner party that, were he told he had only a short time to live, he would strap himself with dynamite and embrace the Supreme Court justice he feared and hated most. A few years later, my friend died—peacefully, at home, in his bed, without having committed a high-profile suicide bombing.

Art and life abound with examples of what the fatally ill intend to do, succeed in doing, or fail to do during their last months of life. Akira Kurosawa’s beautiful film Ikiru concerns a bureaucrat who has spent his career behind a desk and whose impending death inspires him to take what is (for him) a heroic stance and arrange the construction of a children’s playground. In Henry James’ The Wings of the Dove, the ailing American heiress Milly Theale travels to Venice, where she falls under the spell of a gold-digging suitor, Merton Densher. After learning that Densher and his fiancée have conspired to inherit her fortune, she dies, but not before leaving Densher a sum that will trouble his conscience—and effectively end his engagement to his attractive co-conspirator. The dying protagonist of Anton Chekhov’s “Peasants,” a waiter in a Moscow hotel, decides to take his wife and daughter back to his native village so that he can finish his life amid the comforts of home—a remembered paradise that turns out to be a hell populated by greedy, resentful relatives who can hardly wait for him to expire and relieve them of the financial and emotional strains created by his presence.

And what do artists and writers do when they themselves are faced with the imminence of death? One of Pablo Picasso’s final works is a powerful self-portrait: the painter’s face as a skull with eyes that seem to glow with rage and terror. Decades after writing The Death of Ivan Ilyich, which might be considered a worst-case end-of-life scenario, a narrative of profound regret and physical agony unconvincingly mediated by the ministrations of a saintly peasant, Leo Tolstoy resolved to spend the short span remaining to him as a wandering mendicant; he fled his home and died in a railway station, amid what today would be called a media circus. Terminally ill with liver disease, Roberto Bolaño, whose earlier novella By Night in Chile was framed as the deathbed confession of a priest who worked for the Pinochet regime, wrote his masterpiece, 2666, a nine-hundred-page epic novel intended as an exploration of the mystery of evil—and as a possible source of income for his widow and two children; so eager was he to generate income for his survivors that, under the impression it might increase sales, Bolaño suggested that his five-part novel be published, posthumously, in five separate sections. I say all this because it is impossible to read Tony Judt’s last two books without seeing them at least partly as what they were: a conscious and purposeful final project.

In 2008, at the age of sixty, Judt—historian, public intellectual, political philosopher, the founder and director of New York University’s Remarque Institute, and an author whose books include Ill Fares the Land and Postwar: A History of Europe Since 1945—was diagnosed with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), commonly known as Lou Gehrig’s disease. During the two years that separated that diagnosis and his death, Judt managed to write—and later, as the disease rapidly deprived him of his motor skills, to dictate—“a small political book, a public lecture, some twenty feuilletons reflecting on my life, and a considerable body of interviews directed toward a full-scale study of the twentieth century.” After his death, the feuilletons were collected and published as The Memory Chalet, while the interviews form the basis of Thinking the Twentieth Century.

Twelfth-night (The King Drinks), by David Teniers the Younger, c. 1634–1640. Prado Museum, Madrid.

Early on in both books, the reader is made aware of the particular circumstances and pressures under which they were written. “The salient quality of this particular neurodegenerative disorder,” Judt tells us in The Memory Chalet, “is that it leaves your mind clear to reflect upon past, present, and future, but steadily deprives you of any means of converting those reflections into words. First you can no longer write independently, requiring either an assistant or a machine in order to record your thoughts. Then your legs fail and you cannot take in new experiences…Next you begin to lose your voice: not just in the metaphorical sense of having to speak through assorted mechanical or human intermediaries but quite literally in that the diaphragm muscles can no longer pump sufficient air across your vocal chords to furnish them with the variety of pressure required to express meaningful sound. By this point you are almost certainly quadriplegic and condemned to long hours of silent immobility, whether or not in the presence of others.”

During the day Judt’s condition was almost bearable, but night—as we could imagine, if we’d let ourselves—was when the real torments began. “I leave bedtime until the last possible moment compatible with my nurse’s need for sleep. Once I have been ‘prepared’ for bed I am rolled into the bedroom in the wheelchair in which I have spent the last eighteen hours. With some difficulty…I am maneuvered onto my cot. I am sat upright at an angle of some 110 degrees and wedged into place with folded towels and pillows, my left leg in particular turned out balletlike to compensate for its propensity to collapse inward. This process requires considerable concentration. If I allow a stray limb to be mis-placed, or fail to insist on having my midriff carefully aligned with legs and head, I shall suffer the agonies of the damned later in the night.”

To say that this passage is unforgettable is not praise but description. No one who reads the essay can fail to recall it, in some detail. We find ourselves cheering on the mind in its struggle against the mutinous body and thankful, as Judt was, for the partial victory achieved by his retreat into the past. “My solution has been to scroll through my life, my thoughts, my fantasies, my memories, mismemories, and the like until I have chanced upon events, people, or narratives that I can employ to divert my mind from the body in which it is encased.”

What follows in The Memory Chalet is a series of brief essays, each of which begins with a specific and personal recollection—of Judt’s childhood in England, his education at Kings College, Cambridge, and at the Sorbonne, his encounters with Zionism and Marxism, his career as an academic, writer, and public figure. What is striking is that none of this feels like a solipsistic exercise, a simple memoir, or even really a mental diversion intended solely to take the author’s mind off his body. For Judt, the past is both private narrative and footnote to the history of the times in which he lived.

In The Memory Chalet, an account of Judt’s alienation of a Jewish boy, a member of an outsider minority in postwar London, widens into a discussion of Jewish identity and experience. A problematic stay on a kibbutz in Israel—Judt was a left-wing Zionist during his early twenties—informs a consideration of the relationship between American Jews and Israel; reflections such as these made the outspoken Judt the object of frequent criticism from American Jewish intellectuals who disagreed with his highly critical view of Israel’s response to the issue of Palestinian statehood.

Recollections of a ferocious, feared, and beloved high-school German teacher known as Joe inspire a series of ruminations on the ways in which education has changed over the last half century: “Nowadays, almost no one is even taught German. The consensus appears to be that the young mind can handle but one language at a time, preferably the easiest. In American high schools, no less than in Britain’s egregiously underperforming comprehensive schools, students are urged to believe that they have done well—or at least the best they could. Teachers are discouraged from distinguishing among their charges; it is simply not done to do as Joe did and praise first-rate work while damning the lesser performers.” In one of the book’s most effective essays, memories of the Green Line bus that Judt took as a boy to school are expanded to illuminate the pervasiveness of the British class system, as well as the changing urban landscape.

In Thinking the Twentieth Century, Judt found yet another strategy for dealing with the catastrophic diminutions inflicted by his illness. Once a week through the winter, spring, and summer of 2009, the historian and writer Timothy Snyder took the train from New Haven to New York City, and in Judt’s downtown apartment conducted an ongoing conversation about topics that included the history of the French Communist Party, the role of the intellectual in the United States and Europe, the origins of fascism, and the impact of World War I. The book contains minibiographies of British spies and prime ministers and of French politicians, examinations of the problems facing American journalists, historians, and academics. Judt and Snyder reflect on the uses and abuses of memory, the dangers of historical illiteracy, their own—and others’—responses to the ideas of Karl Marx, Friedrich Engels, Léon Blum, and, more recently, David Brooks and Thomas Friedman.

Judt considers the intellectual appeal of Marxism: “Marxism held a distinctive attraction, not only for that first generation of educated, intellectual critics, but right up to the 1960s. Marxism, we tend to forget, is a marvelously compelling account of how history works, and why it works. It is a comforting promise to anyone to learn that history is on your side, that progress is in your direction. This claim distinguished Marxism in all its forms from other contemporary radical products at the time.” He analyzes the tensions that created—and then destroyed—Léon Blum’s Popular Front government in France: “It did not seem implausible in those years to fear that the final battle would be between communism and fascism, with democracy squeezed in the middle: you had better know which side you were going to choose.” And he is bravely critical of those of his contemporaries who, in the run-up to the U.S. invasion of Iraq, took, in his view, a severely limited view of the role of the intellectual: “Instead of asking questions, they all behaved as though the function of the intellectual was to provide justification for the actions of nonintellectuals. And I just remember feeling profoundly shocked and also feeling very lonely.”

Thinking the Twentieth Century is, as Snyder writes in his introduction, “a history of modern political ideas in Europe and the United States. Its subjects are power and justice, as understood by liberal, socialist, communist, nationalist, and fascist intellectuals from the late-nineteenth through the early-twenty-first century. It is also the intellectual biography of the historian and essayist Tony Judt, born in London in the middle of the twentieth century, just after the cataclysms of the Second World War and the Holocaust, and just as communists were securing power in Eastern Europe. Finally, it is a contemplation of the limitations (and capacity for renewal) of political ideas, and of the moral failure (and duties) of intellectuals in politics.”

In these last works, Judt endeavored to come to terms with the questions raised by the most important political theories and historical events of the last century, to explain and clarify whatever conclusions he’d reached. He supported these conclusions with memories and personal experiences, with the impressive, even astonishing, amount of factual information he’d retained, with the wealth of material in the huge library of books he’d read, analyzed, and assimilated—and with strong opinions, especially about the writings and political stances of his contemporaries.

By the Table, by Henri Fantin-Latour, 1872. Musée d'Orsay, Paris.

What comes through, in both books, is that Judt lived through, and thought deeply about, the events and currents that shaped the last century—and will continue to influence our own. Born a few years after the Holocaust, having experienced first the theoretical appeal of communism and Zionism and later the problems that occurred when those ideas were put into practice, having learned the Czech language and become deeply involved in Eastern European society before and after the Berlin Wall, Judt was not only professionally and intellectually equipped to judge these historical movements and currents but also understood that the history, had been, for many, nothing less than a matter of life and death: communism, fascism, and Zionism were social experiments born out of certain necessities and conditions, experiments that came with enormous human costs.

Though his writing, and what we gather of his conversation, was enlivened by charm, there is no question about the fact that he took all this with enormous seriousness. His essays, and his discussions with Snyder, raise questions that are fundamentally moral. How can a government best meet the needs—economic, educational, social, political—of its population? How should the rights of the individual be weighed against, and protected from, the aims of the state? In what cases should a powerful nation, such as the United States, intervene in the affairs of other countries? And what is the role of the public intellectual in helping to form the opinions of a population and its leaders?

Perhaps what’s most touching about Judt’s book is the sense of urgency and of mission that one finds in its pages. Judt believed that these questions—ideas of freedom, responsibility, morality, justice—were important to think about clearly, without cynicism, and that it was the intellectual’s duty to stand slightly outside his society and to speak honestly and bravely about its past, its present, and its future. One feels, throughout, his hope and his belief that something could be done, that brave, right-thinking individuals might possibly effect social change, as they did in Eastern Europe. Surely, there are those who will take up these debates where Judt left off, instead of—as so often seems to be the case—leaving the fate of our beleaguered world for the climatologists and economists to comment on and watch, ineffectively and mournfully, from the sidelines.

Drunkenness is the very sepulcher / Of man’s wit and his discretion.

—Geoffrey Chaucer, 1390One could say that the heart of Judt’s final project, his legacy, was to leave behind a record of how someone (in this case, a brilliant, well-informed intellectual historian with an enduring faith in social justice and human decency) thinks. Of course, one of the pleasures of reading any truly interesting thinker and writer is the opportunity it offers to leave the familiar (and limited) confines of one’s own mind and enter into the broader and very different expanses of another. But the form and substance of Thinking the Twentieth Century makes the reader unusually aware of the process of thought—how the mind moves from the particular to the general, from literature to philosophy, from decade to decade, idea to idea.

Possibly this has something to do with the irony of Judt’s disease and of its cruel ability to prove how well the mind can continue to function on its own with minimal help and only resistance from the body. In both books, in the opening of The Memory Chalet and in the following passage from Thinking the Twentieth Century, we can observe Judt not only thinking, but also thinking about the act of individual and collective thinking:

[History and memory] are step-siblings—and thus they hate one another while sharing just enough in common to be inseparable. Moreover, they are constrained to squabble over a heritage they can neither abandon nor divide.

Memory is younger and more attractive, much more disposed to seduce and be seduced—and therefore she makes many more friends. History is the older sibling: somewhat gaunt, plain, and serious, disposed to retreat rather than engage in idle chitchat. And therefore she is a political wallflower—a book left on the shelf…

To allow memory to replace history is dangerous. Whereas history, of necessity, takes the form of a record, endlessly rewritten and retested against old and new evidence, memory is keyed to public, nonscholarly purposes: a theme park, a memorial, a museum, a building, a television program, an event, a day, a flag. Such mnemonic manifestations of the past are of necessity partial, brief, selective; those who arrange them are constrained sooner or later to tell partial truths or outright lies—sometimes with the best of intentions, sometimes not. In either event, they cannot substitute for history.

Thus, the exhibition at the Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington does not record or serve history. It is selectively appropriated memory, applied to a laudable public purpose. We may approve in the abstract, but we should not delude ourselves as to the outcome. Without history, memory is open to abuse.

Our interest in hearing Judt talk is enhanced by Thinking the Twentieth Century’s conversational form. Snyder, himself the author of the thoughtful and well-written Bloodlands: Europe between Hitler and Stalin, is an excellent interlocutor. Some of the book’s most striking and memorable moments occur when the two men focus on a subject at length—when both apply their intelligence to the same question. Here is how Snyder takes up the question of how memory differs from history:

One way to mark the difference between history and memory is to notice that there is no verb for history. You know, if someone says, “I’m making history,” they mean something very special and usually ludicrous. To “historicize” is a technical term, conventionally restricted to scholarly exchange. By contrast, “I remember” and “I recall” are perfectly conventional things to say.

This points to a real difference: memory exists in the first person. If there isn’t a person, there isn’t a memory. Whereas history exists above all in the second or third person. I can talk about your history, but I can only talk about your memory in a very limited and usually offensive or absurd sense. And I can talk about their history, but I can’t really talk about their memory, unless I know them extraordinarily well for some reason…

Because memory is in the first person, it can be constantly revised, and it becomes more personal with time. Whereas history, at least in principle, takes the other direction: as it is revised, it becomes ever more open to the perspective of third parties and thereby potentially universal. A historian can start with concerns which are immediate and personal—they perhaps have to be—and then work away from them. Sublimating his starting perspective, he comes up with something altogether different.

In the last two sentences, Snyder has essentially alluded to Judt’s method throughout this book and The Memory Chalet, but Judt seems not to notice. His mind has already moved on to another aspect of the question under discussion: “I would dissent partially in one respect. Public memory is an incarnated, collective first-person plural: ‘we remember…’ The result is calcified summaries of collective memory, and once the remembering persons are gone, these summaries substitute for memory and become history.”

It’s heady intellectual Ping-Pong for those who like this sort of thing, which I do. Judt and Snyder share the rare ability—rarer still among academic historians—to be abstract without being boring. In addition, both men—they are, after all, historians—clearly retain a tremendous amount of factual information and have thought deeply about the past. I’d been working on a piece of fiction set partly in France during the 1930s and had thought I knew all I needed to know about that era, but several passages in Judt’s book made me begin to think in a new way about the optimism and the terror that coexisted in France during the years that led up to World War II. So I feel quite grateful for having had the occasion to read it.

Thinking the Twentieth Century is a book that needn’t be read straight through, but rather by the chapter, like a collection of short stories. Throughout, there are passages that one wants to remember, copy out, and quote. Consider, for example, this conversation about the historian’s responsibility—moral responsibility—to write clearly and comprehensibly, a passage that may help explain why one would want to eavesdrop on two men, one of them dying, talking about Zionism, or Kafka: “A badly written history book is a bad history book,” Judt says. “Sadly, even good historians are often clumsy stylists, and their books languish unread.”

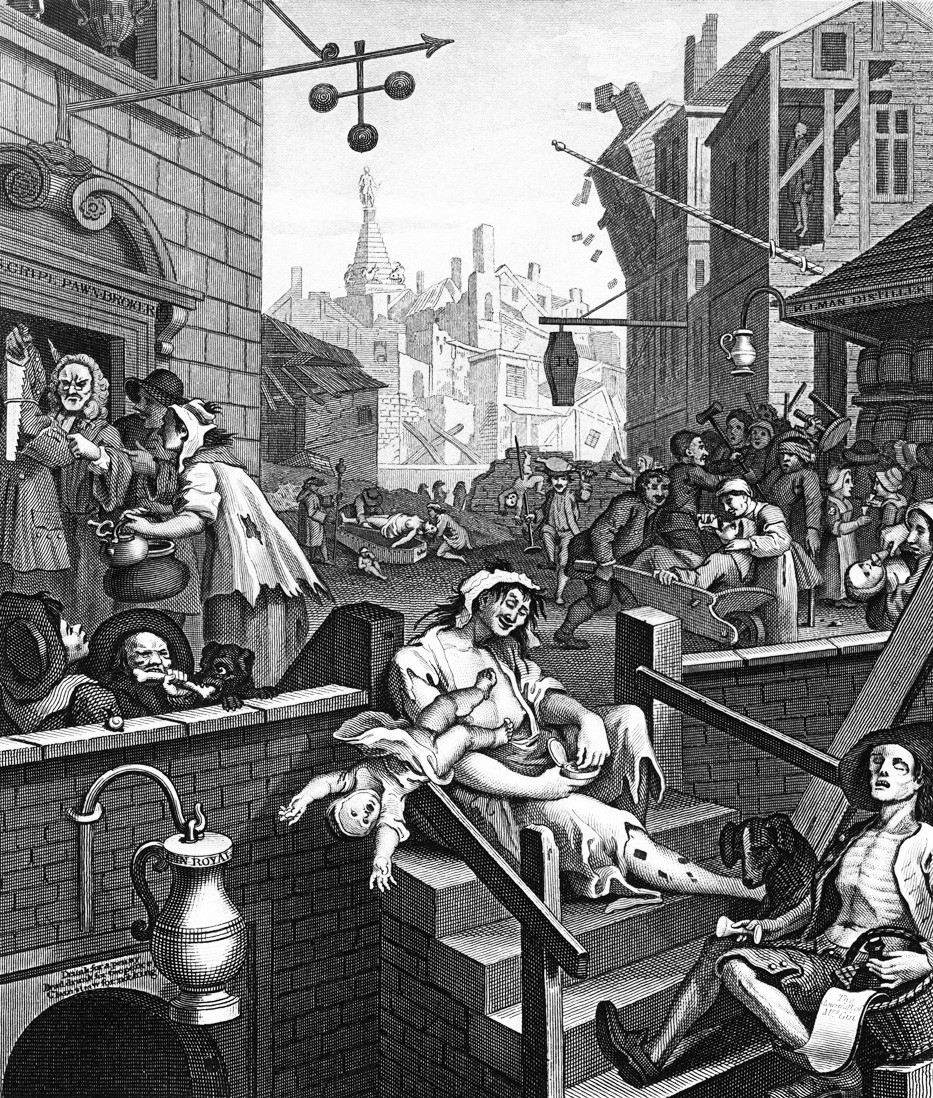

Gin Lane, by William Hogarth, 1751.

Snyder says he feels “as though there’s an ethical aspect to this, as well. And I don’t know how to put it except in a way which is going to sound dreadfully eighteenth-century and metaphysical, but—”

“What’s wrong with the eighteenth century? Best poetry, best philosophy, best buildings…”

“—that we owe something to the language. That not only should we write well because that means that people buy our books and not only should we write well because that is what history is but also because there aren’t that many crafts anymore that have a responsibility to the language. Whatever sort of responsible craftsmanship remains, we’re right in the middle of it.”

To which Judt replies, “The obvious contrast would be the novelist. Ever since the rise of the ‘new’ novel in France in the fifties and sixties, novels have been colonized by nonstandard forms of language. This is hardly new: remember Tristram Shandy, not to mention Finnegans Wake. But historians cannot follow suit. A nonstandard history book—written with no regard to sequence or syntax—would be simply incomprehensible.”

This was the sort of conversation that Tony Judt had with Timothy Snyder. These books are what he decided and was able to do during his last two years. He left a record, a sort of intellectual documentary that allows us to forget, at least for stretches of time, what would have been constantly and impossibly distracting in a film or an audio recording: the vision and sound of a sharp mind turning like a propeller inside a body that needed a machine to breathe. We can read his books and feel that we are hearing someone’s voice and being shown an exceptional mind at work.