He that would eat the nut must crack the shell.

—Plautus, 200 BCPushing Paper

Paperwork has never fit comfortably into our idea of what work means—it has no heroes and few sympathies.

By Ben Kafka

Copyshop, photograph by Thomas Demand, 1999.

Why is there no Norton Anthology of Paperwork? Though the trove of Franz Kafka manuscripts hidden away in safe-deposit boxes has attracted more attention from the mainstream media, the collection of newly translated memos that the author crafted during his years as a staff lawyer for the Workers’ Accident Insurance Institute in Prague is the real treasure. Kafka: “The Institute is convinced that if the case were such that the risk category for sheep’s-wool weaving mills had been higher than the category for cotton-weaving mills, pressure would have been exerted to get the mixed-weaving mills classified as cotton-weaving mills, a change that would, if only coincidentally, have corresponded to actual conditions.”

Not bad. Nor is Kafka the only important modern author to have spent much of his time and energy at work on sentences like these. Who wrote, “I paid a visit to the Ministry of Public Instruction. There I verified that you have only one justificatory document to provide…I am confident that the minister, in his letter to the prefect of La Manche, will not ask for anything more. I thus believe that writing this letter of justification and transmitting it to monsieur the prefect, explaining to him the particular circumstances in which you find yourself, should suffice for him to recognize his error”?

Spanish Blacksmiths, II, by Ernst Josephson, 1882. National Museum of Art, Architecture and Design, Oslo, Norway.

Or who wrote, “Probationary faculty are reminded that enrollment, the needs of the department, teaching excellence, service, and the candidate’s scholarly productivity are essential considerations in annual pretenure reviews, third-year reviews, and tenure recommendations”?

If you guessed Alexis de Tocqueville and my dean, congratulations. Like Kafka, they are masters of the craft. Tocqueville’s sentences are confident, sensible, reassuring. At the time, he was working as a member of the council general of the prefect of La Manche; the mayor of St. Sauveur-le-Vicomte, to whom this memo was addressed, almost certainly grasped its meaning and import after only one reading, which is the best you can ask for in circumstances like these.

While it requires more than one reading, the dean’s memo is also artful in its way. It performs a perlocutionary wonder, simultaneously filling the tenure-track (“probationary”) faculty member with existential dread and intellectual smugness. Why is the goal “excellence” in teaching but only “productivity” in scholarship? Does this mean I can get away with producing crap, as long as I produce it in sufficient quantities? As long as I keep fertilizing the fields of knowledge?

Actually, we shouldn’t be too hard on the dean, who is a capable administrator and a talented scholar. The chances that she wrote or even read this sentence are slim. It is much more likely that one of her assistants copied and pasted it from some other letter, where it had been copied and pasted from yet another letter, and so on, back to a lunch meeting when an ad hoc committee of senior faculty members with kids and credit-card bills and elderly aunts in the hospital and papers to grade sat down and composed it over “lunch provided.” It’s boilerplate, which, the Oxford English Dictionary tells us, once referred to sheets of iron, between a quarter- and a half-inch thick, that were intended for the manufacture of boilers but were also readily adaptable for other purposes.

My Norton Anthology of Paperwork would include some of the finest historical examples of boilerplate, alongside selections of letterhead, fill-in-the-blank forms, fine print, and the history of that wonderfully poetic instruction, “last name, first.” Indeed, the boilerplate metaphor could itself be a metaphor for a larger transformation, two centuries in the making, that has taken many of us away from extracting coal and forging iron and assembling boilers toward waiting for an inspector to come sign off on a certificate that needs to be filed with the local Department of Buildings. Paperwork occupies us and preoccupies us, whether we are maritime lawyers or nail-salon owners, congressional aides or human-resource managers, college professors or freelance web designers.

Which leads me to wonder: why is there so little solidarity among all of us paperworkers? Why do we so often feel sorry for ourselves, so burdened by paperwork of one kind or another, while having so little sympathy for others—the dean who signs off on a clumsy sentence, the secretary who misaddresses an envelope, the paralegal who misses a deadline, the insurance agent who misfiles a claims form?

The reason, I think, is that paperwork has never fit comfortably into our idea of what work means, or what it means to work. This might explain, for example, why paperwork has so few heroes in mythology, literature, cinema, real life. There is no John Henry or Mighty Casey or Casey Jones or Rosie the Riveter inspiring us to work better or harder. The sweaty iron worker is an erotic figure; the sweaty insurance salesman a figure of derision. Even when it’s most of what we do, it’s not what we think of as what we really do. “I am a professor who also happens to write memos, reimbursement requests, self-evaluations, letters of recommendation, grant applications, conference budgets, procedural-revision plans, reports to the accreditation committee.” Not “I am a writer of memos, reimbursement requests, self-evaluations, letters of recommendation, grant applications, conference budgets, procedural-revision plans, reports to accreditation committees who also happens to be a professor.”

In an influential essay from 1977, John and Barbara Ehrenreich attempted to identify the class of people who spend most of their time this way. They called it “the professional-managerial class” and gave it a nifty abbreviation. The PMC was not the proletariat nor the petty bourgeoise nor the bourgeoisie proper. Nor would “middle class” do, since it was clearly an ideological ploy, intended to obscure objective antagonisms within and between classes. “We define the professional-managerial class as consisting of salaried mental workers who do not own the means of production and whose major function in the social division of labor may be described broadly as the reproduction of capitalist culture and capitalist class relations.” This is 1970s speak for a class of people who reproduce things rather than produce them, who keep things going or keep things up or keep things interesting while generally keeping things from getting out of control. Working in a less Marxist idiom, the French philosophical team of Gilles Deleuze and Pierre-Félix Guattari called this “the production of production.”

Sounds interesting, right? The problem is that all this paperwork is actually kind of tedious. Even when things go wrong, they tend to go wrong tediously. There are relatively few paperwork emergencies: you might find yourself calling 311, but never 911. If you find yourself short of breath, it’s more likely a heart condition than any sense of exhilaration. One effect of this tedium is that we routinely grow bored, distracted, alienated at work. Our minds wander toward sex and credit-card bills. We spend hours surfing the web, which turns out to be much less challenging and enjoyable than the verb makes it sound. Our backs ache, our carpal tunnels throb, our vision blurs. We begin to suffer from other, less localizable complaints. And then even after a long, tiresome day we have trouble falling asleep, trouble staying there. We go to the gym, which helps a little, but it’s hard to escape the idea that our minds, like our legs, are always racing on treadmills, going nowhere fast. It’s like that scene in Modern Times where Charlie Chaplin continues twitching and turning his wrenches even after the assembly line has come to a halt, except in this case the muscle memory is in our brains.

And like a treadmill, it takes a lot of effort, dexterity even, to stay in one place. No wonder this new class is so anxious. “The son of the chairman of the board may expect to become a successful businessman (or at least a wealthy one) more or less by growing up,” the Ehrenreichs noted. “The son of a research scientist knows he can only hope to achieve a similar position through continuous effort.” Most of these efforts are directed toward acquiring the kind of fluency with words and numbers that allow them to become good paperworkers. Dental hygiene and computer skills also count for a lot. But the most important thing of all is psychological well-being, whether that means “healthy self-esteem” or “playing well with others” or “good at sharing” (not to be confused with “indiscreet”). You don’t want your son or daughter to become that guy, the one played by Steve Carell in The Office or Carol Kane in Office Killer.

Two of the smartest inquiries into the psychopathology of paperwork were published in the nineteenth century: Herman Melville’s Bartleby, the Scrivener: A Story of Wall Street (1853) and Gustave Flaubert’s Bouvard and Pécuchet (1881). Critics have tended to interpret these texts as allegories of the creative process or capitalism or some other, loftier problem. This may well be the case. But if they were allegorical, they were also topical. Melville and Flaubert were both interested in the physical and psychical consequences of office work.

The critic and biographer Andrew Delbanco has suggested several possible sources of inspiration for Melville’s story: the character of Nemo in Charles Dickens’ Bleak House, serialized in Harper’s shortly before Melville started work on Bartleby; an article in the Albany Register from 1852 about the Dead Letter Office where letters accumulate “containing undelivered love notes, locks of hair”; the first chapter of a novel printed as an advertisement in the New York Times from 1853 about a legal clerk named Adolphus Fitzherbert whose “countenance was shaded with constitutional or habitual melancholy”; or Melville’s visits to the law office of his uncle, Peter Gansevoort.

Dolce Far Niente, by John Singer Sargent, c. 1907. Brooklyn Museum, New York.

Bartleby is narrated by a lawyer whose thirty years of practice have “brought me into more than ordinary contact with what would seem an interesting and somewhat singular set of men, of whom, as yet, nothing that I know of has ever been written—I mean the law copyists, or scriveners.” Four centuries of print technology had done little to ease their burden; even in this era of mechanical reproduction there was as yet no cheap and fast way of making an exact copy of a document, let alone a fair copy. Indeed, in the 1850s, a copyist’s tools still resembled those of a medieval monk in many ways, not least in the reliance on a quill pen, the steel nib still being relatively novel. Like their medieval predecessors, they sat at angled desks; like their predecessors, too, they worked either by natural light or candelight. Industrially produced wood-pulp paper was cheaper and more plentiful than parchment, which meant that it cost less to start all over again, but the laboriousness of copying meant that mistakes remained inevitable, costly or otherwise.

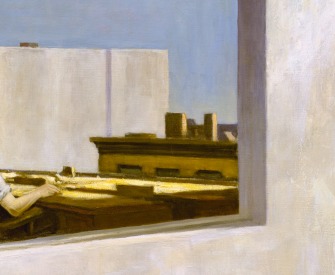

Melville carefully attended to these details. One of the copyists struggles with his writing implements, constantly splitting then mending his nibs, splattering blots of ink on the documents. Meanwhile another fiddles constantly with the height of his desk: “He put chips under it, blocks of various sorts, bits of pasteboard, and at least went so far as to attempt an exquisite adjustment, by final pieces of folded blotting paper.” The light in the law offices at No.— Wall Street is perpetually dim, with windows looking out onto a brick wall, at one side, and a shaft, on the other. As the lawyer remarks, “This view might have been considered rather tame than otherwise, deficient in what landscape painters call ‘life.’”

Into this office comes Bartleby, whom the narrator sets up in a corner of his own office, behind a high green folding screen, out of sight but within earshot. Things start off well enough; the copyist does his work and does it scrupulously. And as the narrator himself admits, this is not easy work. To verify the accuracy of a copy, one copyist will read the copy aloud while another checks it against the original. “It is a very dull, wearisome, and lethargic affair,” the narrator tells us. “I can readily imagine that, to some sanguine temperament, it would be altogether intolerable. For example, I cannot credit that the mettlesome poet Byron would have contentedly sat down with Bartleby to examine a law document of, say five hundred pages, closely written in crimpy hand.”

The problem, of course, is that Bartleby turns out be no more willing to work than the mettlesome poet. On Bartleby’s third day at the office, the lawyer summons him over to assist in checking a copy of some document or another:

Imagine my surprise, nay, my consternation, when, without moving from his privacy, Bartleby, in a singularly mild, firm voice, replied, “I would prefer not to.”

I sat awhile in perfect silence, rallying my stunned faculties. Immediately it occurred to me that my ears had deceived me, or Bartleby had entirely misunderstood my meaning. I repeated my request in the clearest tone I could assume, but in quite as clear a one came the previous reply, “I would prefer not to.”

“Prefer not to,” echoed I, rising in high excitement and crossing the room with a stride. “What do you mean? Are you moonstruck? I want you to help me compare this sheet here—take it,” and I thrust it toward him.

“I would prefer not to,” said he.

The story follows the consequences of Bartleby’s refusal not only to copy but to cooperate with any sort of instruction whatsoever. He remains where he is, behind his screen, day and night, impervious to requests, entreaties, blandishments. The other copyists become resentful, clients ask questions, colleagues gossip. The formula “I would prefer” works its way into the conversation of everyone in the office. Eventually the lawyer decides to relocate his office; Bartleby stays behind in the building. The landlord, finding this bad for property values, has the copyist shipped off to prison, where he wastes away, preferring not to eat or drink or exercise. The story concludes with a rumor that the narrator heard in the months after Bartleby’s death. Before coming to work at the law office, it seemed, Bartleby had worked in the Dead Letter Office, delivering undeliverable mail to the incinerator. “Sometimes from out of the folded paper the pale clerk takes a ring—the finger it was meant for, perhaps, moulders in the grave; a banknote sent in swiftest charity—he whom it would relieve, nor eats nor hungers any more; pardon for those who died despairing; hope for those who died unhoping; good tidings for those who died stifled by unrelieved calamities. On errands of life, these letters speed to death.”

You can be up to your boobies in white satin, with gardenias in your hair and no sugar cane for miles, but you can still be working on a plantation.

—Billie Holiday, 1956Some of the greatest minds in modern criticism and philosophy have pondered the meaning of Bartleby’s refusal to work. Their interpretations range from brilliant to clever to silly. I would only add that there is nothing particularly surprising about Bartleby’s one-man job-action. I wouldn’t want to copy a five-hundred-page legal document “closely written in crimpy hand” either. And once I realized what I could get away with—get away without—why stop there? By withdrawing his labor, he forces us to recognize that what he does is labor. To recognize that paperwork is also work.

No, there’s nothing very mysterious about Bartleby’s motivations. The narrator’s willingness to tolerate this work stoppage is what needs to be explained. Rather than beat him up or lock him out or have him arrested—the traditional ways of responding to striking workers in industrial America—the lawyer holds onto the scrivener. One of the best essays written on this subject is by the psychoanalyst Christopher Bollas, who insists that this story is more about the narrator than the narrated. As the story proceeds, it becomes increasingly clear that the lawyer identifies with his clerk. To be sure, it is an ambivalent identification, but that only makes it all the more powerful. “All that is left to the grieving narrator is a profound recognition and sense that something terribly needy, horribly isolated, ‘incurably forlorn,’ is lost forever.”

This sadness is as much political as existential. The narrator expresses his identification with Bartleby in the language of mid-nineteenth-century Christian socialism: “For the first time in my life a feeling of overpowering, stinging melancholy seized me. Before, I had never experienced aught but a not-unpleasing sadness. The bond of a common humanity now drew me irresistibly to gloom. A fraternal melancholy! For both I and Bartleby were sons of Adam.” And yet the narrator cannot quite transform this identification into a proper sense of solidarity. The thing he and his copyist have most profoundly in common, paperwork, is also what drives them apart. The copying has to get done, whether Bartleby prefers to or not. The story’s famous last lines, “Ah, Bartleby! Ah, humanity!” express the narrator’s bad conscience, which should also be ours. What our fellow paperworkers need isn’t pity, but patience.

“No time for reflection! Let’s copy! The page must be filled, the ‘monument’ completed. All things are equal: good and evil, beautiful and ugly, insignificant and characteristic. There is no truth in phenomena. End with a view of our two heroes leaning over their desk, copying.”

Thus concludes Gustave Flaubert’s unfinished novel Bouvard and Pécuchet. The great Flaubert scholar Enid Starkie notes that the author experimented with at least two other titles before settling on this one: The Two Copyists and The Two Woodlice. Like Melville, Flaubert drew inspiration from a number of popular and not so popular sources concerning the lives of white-collar workers. Among these sources was his own short story, one of the first things he ever published, at the age of fifteen, “A Lecture on Natural History—Genus: Clerk.”

You ought to see this interesting biped in the office, copying its register. It has removed its coat and collar, working in shirtsleeves and wearing its wool vest.

It is hunched over the desk, with its quill tucked above its left ear. It writes slowly, savors the smell of ink, and enjoys watching it cover a huge sheet of paper. It repeats to itself what it writes, with its mumbling giving off a constant nasal sound. But when it is in a hurry, it hastily scatters periods, commas, dashes, “The Ends,” and paragraphs. This is the height of talent.

The protagonists of Bouvard and Pécuchet meet one hot Paris Sunday. Bouvard works as a copyist for a firm that handles Alsatian textiles; his companion is a copyist in the Ministry of the Navy. They strike up a conversation, take a walk, share dinner, become fast friends. “What we call ‘love at first sight’ holds true for all sorts of passions,” Flaubert remarks. When Bouvard comes into an unexpected inheritance, he decides to invite his new best friend to take an early retirement with him. They will move to the countryside and devote their remaining days to something, anything, other than copying.

Off they go, like so many investment bankers reinventing themselves as cheesemakers or syrup sappers in Vermont. They use part of the inheritance to purchase a hundred-acre farm in Calvados, where they settle in for the duration. The duration of what? They’re not quite sure, and pretty soon begin to plant small crops, which fail; raise poultry and livestock, which die; make preserves, which spoil; brew speciality beers, which make them sick. They grow interested in chemistry, then medicine, then geology, then local history, then historical fiction. When the Revolution of 1848 comes, they get caught up in local politics with an enthusiasm matched only by their ignorance. Having failed at politics, they try love; after failing at love, they set out to improve their physiques through gymnastics; after failing at gymnastics, they turn to spiritualism. And so it goes.

Flop House, by Edward Millman, 1937. Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, D.C.

The novel’s punchline, repeated over and over again, is that with every setback, the clerks send away for more books and guides to instruct them on how to plant or brew or stretch. The copyists may escape the office, but they can’t escape their nature. Even left to roam free in the countryside, they continue to copy, copy, copy. Flaubert famously boasted in a letter to Edma Roger des Genettes that he had taken notes on over fifteen hundred books in an effort to make his characters’ ignorance more realistic. Six years were spent on Volume 1 alone. Volume 2, never completed, was to consist entirely of the notes made by the characters in the course of their research.

“Idiots—those who think differently from you,” Flaubert wrote in the Dictionary of Received Ideas, a work that substituted for the unfinished Volume 2. The irony, or one of them anyway, is that the idiots in this case were those who resembled him, as he spent his last years copying, copying, copying those fifteen hundred volumes. The irony may not have been lost on Flaubert, but too often it’s lost on us. If Bartleby is a reflection on the shortage of solidarity in the world of paperwork, Bouvard and Pécuchet is an example of this shortage. Even Flaubert seems to be laughing at his characters, rather than with them. He can’t quite bring himself to recognize that his own prose might bear some resemblance to theirs. In the novel we witness writing struggling to rescue itself, its sense of itself, from the shame of more practical, and thus more vulgar forms of literacy.

In a marvelous essay published some years ago in The Threepenny Review, the literary critic Rachel Cohen considered the careers of two great poet-clerks, Fernando Pessoa and Constantine Cavafy. The latter had spent over three decades working as a translator for the British colonial administration in the offices of the Third Circle of Irrigation. Cohen cites an interview with one of his fellow clerks, a man named Ibrahim el Kayar, who described how Cavafy would occasionally lock the door to his office: “Sometimes my colleague and I looked through the keyhole. We saw him lift up his hands like an actor and put on a strange expression as if in ecstasy, then he would bend down to write something. It was the moment of inspiration. Naturally we found it funny and we giggled. How were we to imagine that one day Mr. Cavafy would be famous!”

How indeed? We naturally assume that these dramatic gestures, these ecstatic expressions, represent moments of poetic inspiration. The locked room, the voyeuristic gaze, the clerks’ astonishment provide further evidence in favor of what we already know, what we already think we know, that in this scene the poet-clerk is a poet rather than a clerk. We are witnessing an act of creation, not an act of re-creation. Nobody in their right mind would expend that much effort on mere paperwork.

Except, of course, for all of us who do just that.