Because women are by nature weaker than men and because they are most frequently afflicted in childbirth, diseases very often abound in them, especially around the organs devoted to the work of Nature. Moreover, women, from the condition of their fragility, out of shame and embarrassment, do not dare reveal their anguish over their diseases (which happen in such a private place) to a physician. Therefore, their misfortune, which ought to be pitied—and especially the influence of a certain woman stirring my heart—have impelled me to give a clear explanation regarding their diseases in caring for their health.

Because there is not enough heat in women to dry up the bad and superfluous humors which are in them, nor is their weakness able to tolerate sufficient labor so that Nature might expel the excess to the outside through sweat as it does in men, Nature established a certain purgation especially for women: that is, the menses, to temper their poverty of heat. The common people call the menses “the flowers,” because just as trees do not bring forth fruit without flowers, so women without their flowers are cheated of the ability to conceive. This purgation occurs in women just as nocturnal emission happens to men. For Nature, if burdened by certain humors, either in men or in women, always tries to expel or set aside its yoke and reduce its labor.

This purgation occurs in women around the thirteenth year—or a little earlier or a little later, depending on the degree to which they have an excess or dearth of heat or cold. It lasts until the fiftieth year if she is thin, sometimes until the sixtieth or sixty-fifth year if she is moist. In the moderately fat, it lasts until the thirty-fifth year. If this purgation occurs at the appropriate time and with suitable regularity, Nature frees itself sufficiently of the excess humors. If, however, the menses flow out either more or less than they ought to, many sicknesses thus arise, for then the appetite for food as well as for drink is diminished; sometimes there is vomiting, and sometimes they crave earth, coals, chalk, and similar things.

Sometimes from the same cause, pain is felt in the neck, the back, and in the head. Sometimes there is acute fever, pangs of the heart, dropsy, or dysentery. These things happen either because for a long time the menses have been deficient or because the women do not have any at all. Whence not only dropsy, dysentery, or heart pangs occur, but other very grave diseases.

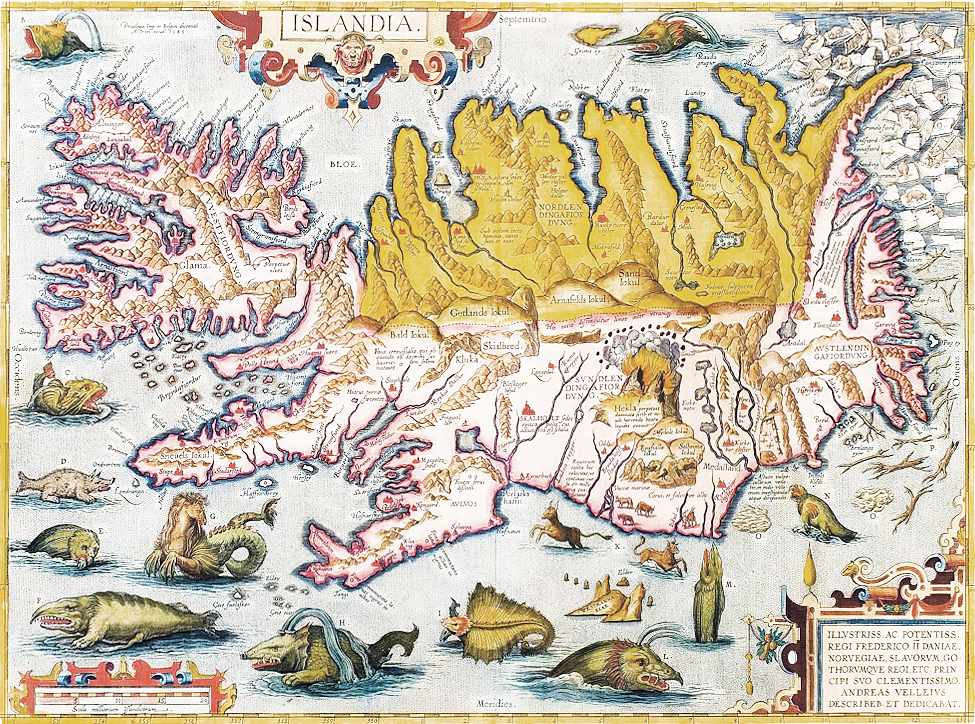

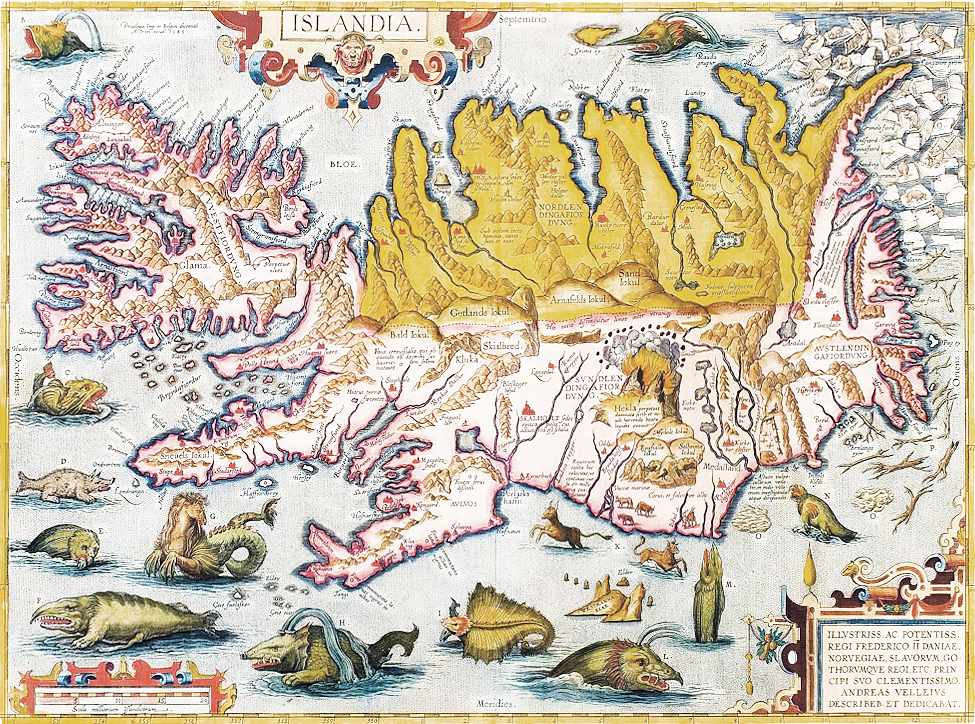

Map of Iceland, by Abraham Ortelius, 1585.

Sometimes there is diarrhea on account of excessive coldness of the womb, or because its veins are too slender, as in emaciated women, because then thick and superfluous humors do not have a free passage by which they might break free. Or sometimes menstrual retention happens because the humors are thick and viscous, and on account of their being coagulated, their exit is blocked. Or it is because women eat rich foods, or because from some sort of labor they sweat too much, just as Rufus and Galen attest: for in a woman who does not exercise very much, it is necessary that she have plentiful menses in order to remain healthy.

Sometimes women lack the menses because the blood in their bodies is congealed or coagulated. Sometimes the blood is emitted from other places, such as through the mouth or nostrils or in spit or hemorrhoids. Sometimes the menses are deficient on account of excessive pain, wrath, agitation, or fear. If, however, they have ceased for a long time, they make one suspect grave illness in the future. For sometimes women’s urine turns red or into the color of water in which fresh meat has been washed. For the same reason, sometimes their face changes into a green or livid color or into a color like that of grass.

Trotula, from Book on the Conditions of Women. The tract was one of many formal writings to emerge from the flowering of the arts and sciences in Salerno that followed from the rediscovery of classical texts and the influx of ideas from the Arabic world. Allegedly written by the first female professor of medicine in the city, it was the most influential compendium of women’s medicine during the Middle Ages.

Back to Issue