Doctors don’t know everything really. They understand matter, not spirit. And you and I live in spirit.

—William Saroyan, 1943The God in the Machine

Americans ask of medicine more than medicine can deliver—not only the cure for death, but also the gift of riches.

By Lewis H. Lapham

The Travelling Quack (detail), by Tom Merry, 1889. Wellcome Collection (CC BY 4.0).

The ordinary course of a cure is carried on at the expense of life: they incise us, they cauterize us, they amputate our limbs, they deprive us of food and blood. One step further, and we are completely cured.

—Michel de Montaigne

President Barack Obama during his first months in office seldom has missed a chance to liken the country’s healthcare system to an unburied corpse, which, if left lying around in the sun by the 111th Congress, threatens to foul the sweet summer air of the American dream. The prognosis doesn’t admit of a second or third opinion. Whether on call to the Democratic left or the Republican right, the attending politicians and consulting economists concur in their assessment of the risk posed by the morbid emissions. The country now pays an annual fee of $2.4 trillion for its medical treatments (16 percent of GDP); the costs continue to lead nowhere but up. Fail to embalm or entomb the putrefying debt, and it’s only a matter of time—ten years, maybe twenty—before the pulse disappears from the monitors tracking the heartbeat on the floor of the New York Stock Exchange.

So say the clinicians in Washington, and I don’t quarrel with the consensus. If I can’t make sense of some of the diagnoses or most of the prescriptions, at least I can understand that what is being discussed is the health of America’s money, not the well-being of its people. The symptoms present as vividly as the manifestations of plague listed in Thucydides’ History of the Peloponnesian War, but they show up as an infection of the body politic caused by the referral of the country’s medical care to the empathy of accountants and the wisdom of drug dealers. Thus the suppurating cruelty and the malignant disparities, among which a few of the most apparent attest to the severity of the disorder:

The United States leads the world in the advancements of medical science, its hospitals splendidly equipped with Magnetic Resonance Imaging machines and artificial hearts, its doctors gloriously decorated with Nobel Prizes, but between 44,000 and 98,000 patients die every year in American hospitals of iatrogenic infections or as the consequence of a mistaken diagnosis or a bungled operation. Medical error ranks as the country’s eighth leading cause of death, more deadly than breast cancer or highway accidents.

American hospitals and doctors are paid for the amount of care they produce, not for its effectiveness or its quality. As often as not the doctors don’t see the patients for whom they prescribe remedies; they look at test results and consult computer screens—their first care is for the treatment of paper.

Americans in 2007 paid $7,421 per capita for healthcare as opposed to $2,840 paid by the Finns and $3,328 by the Swedes, but life expectancy in the United States is not as long as it is in thirty other countries, among them Finland and Sweden; the first-year infant-mortality rate in the United States is higher than it is in some forty other countries, among them Slovenia and Singapore. A newborn child stands a better chance of survival in Minsk and Havana than it does in New York or Washington.

The money allocated to healthcare in most other developed countries (in Canada and France as well as in Germany and Japan) provides medical insurance for the entire citizenry. Not in America; 46 million citizens (15 percent of the population) are uninsured. Patients with sufficient funds can buy a brain implant or a bionic eye, but an estimated 22,000 people died in 2006 for lack of insurance; 59 million other people reported their inability to receive needed medical attention.

Together with the cornucopia of drugs for all seasons (Zoloft, Lipitor, Botox, Viagra, etc.) the American healthcare shopping mall now offers expensive diagnostic tests (CT scan, bone scan, spinal tap, etc.) that allow upward of six million Americans to enjoy the benefit of high-priced bodily home improvements—titanium knees, Peruvian kidneys, two-hour erections, and a sunny disposition. Of the 1.5 million Americans expected to declare personal bankruptcy this year, 60 percent will be forced to do so to pay their medical bills.

The ratio between the country’s shelters for battered women and its shelters for stray animals stands at three to one in favor of the animals.

The anecdotal evidence supports the findings of malignancy. The news media bring recurrent reports of patients denied treatment because they are too old or too sick to deserve an insurance company’s blessing. Friends, family, and chance acquaintances tell of near-death experiences in a hospital emergency room or admitting office. The data suggest that any recuperating of the country’s healthcare system requires the solution of a philosophical problem before treating the political and economic trauma.

The heavy cost of the enterprise follows from our asking of medicine more than medicine can deliver—not only the cure for death, but also the gift of riches. The request is neither new nor uniquely American.

Noga Arikha’s essay in this issue of Lapham’s Quarterly touches on some of the antecedents, mythological and alchemical as well as scientific and historical. The texts elsewhere in the issue echo Sir William Osler’s remark that medicine, always fallible and often absurd, “is a science of uncertainty and an art of probability.” If the assembled witnesses can be said to reach a consensus, it is in their agreement that technology, no matter how defined—as sorcery or prayer, as brain surgery or the syrup of roses—doesn’t govern or control the laws of nature.

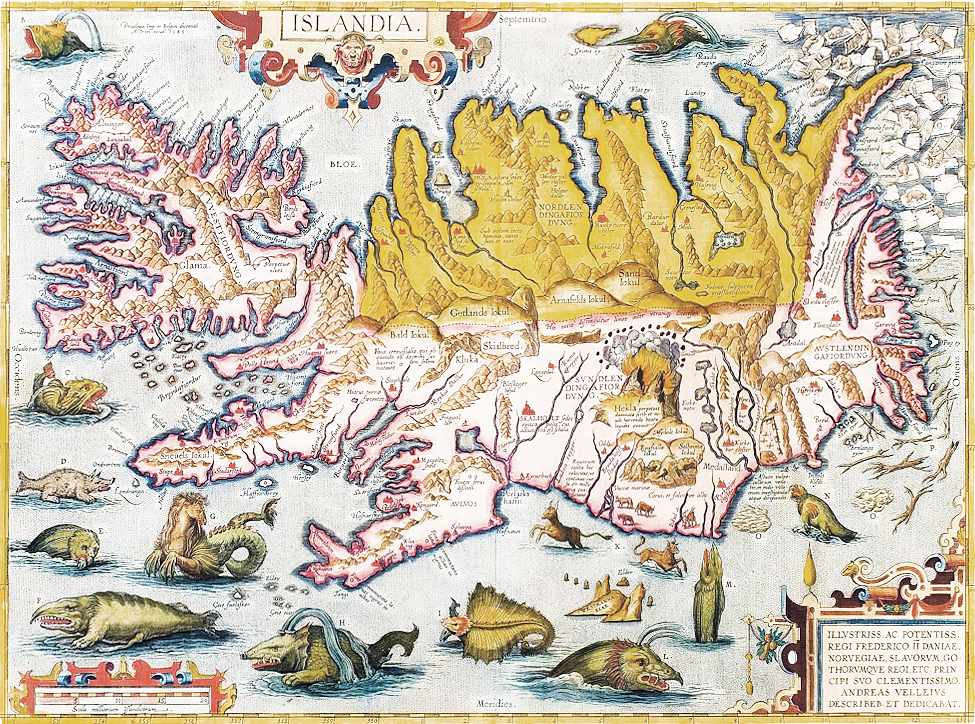

Map of Iceland, by Abraham Ortelius, 1585.

The old truism was more readily apparent in societies unexposed to the chemistry of birth-control pills and the mechanics of a triple coronary bypass. Even an extended stay in an American hospital during the first half of the twentieth century didn’t hold out a higher chance of recovery, and for most illnesses the treatments were therapeutic, not diagnostic; doctors relied on common sense, on the natural resilience of the human body, and the hope that by tomorrow morning the patient would show signs of improvement. A medical practice was likely to consist of five or six doctors who answered weekend and late-night telephone calls, knew the names and ailments of their patients, tended to think of their profession as a public service. Doctors making rounds in public-hospital wards adopted the attitude that

Rudyard Kipling describes in his lecture to the students of Middlesex Hospital’s medical school. It was understood that sooner or later even the most artful physician must acknowledge the presence of death, “the senior practitioner,” whose opinion brings with it the fall of the capital city. In the face of the inevitable defeat, nobody was in the business of performing miracles; what they did perform, the patients as well as the doctors, were the acts of kindness tempered with courage, knowing, as did Seneca, that the strength to confront suffering was to be found in the thought that “you will not die because you are sick but because you are alive.”

The consolations of philosophy were no match for the wonders of medical science raked from the ashes of World War II. Newly armed with antibiotics known to the trade as magic bullets, among them sulfa and penicillin, a new generation of physicians found itself capable of cures for syphilis and tuberculosis as well as for typhoid and scarlet fever. Surgical skills acquired to address battlefield wounds led to further development of the means with which to repair, rehabilitate, and reformulate the human body. Infirmities that John Donne regarded as “perplexed decompositions” and “riddling distempers” began to be seen as factory errors subject to recall in the manner of a malformed Ford Explorer.

Affiliated with the several theories of American exceptionalism and entitlement, the great expectations also were a product of World War II. Prior to the advent of the atomic bomb, answers to the question, “Why do I have to die?” were looked for in the teachings of religion and the languages of art, in Plato’s discourses and the music of J. S. Bach. The experiments conducted at Hiroshima and Nagasaki referred the question to the politicians in charge of the nuclear weapons and to the research scientists clearly destined to discover that death is a preventable disease. America’s military and economic command of the world stage fostered the belief that America was therefore exempt from the laws of nature, held harmless against the evils inflicted on the lesser nations of the earth. For the last sixty years, the intimations of immortality have supported the habits of magical thinking that enable the country’s codependence on both its military-industrial and its medical-industrial complex. As America’s enemy-in-chief, disease serves as a body double for godless Communism, the doctrine of mutually assured salvation as a stand-in for the doctrine of mutually assured destruction.

Not surprisingly, whether alone on a physician’s examining table or as an assembly of petitioners in the consulting rooms of the public-policy debate, the American faithful expect the coming of miracles. President Reagan’s Strategic Defense Initiative (aka “Star Wars”) presumed a technology that not only didn’t exist but was impossible to construct. To serve the purpose assigned to it, the Air Force would have needed to lift into orbit a space platform roughly the size and weight of the state of New Jersey. President Obama’s prescriptions for healthcare reform belong to the same order of imaginary numbers. Just as the doctors don’t see the patients, the patients don’t see the government’s paying of the Medicare bills.

The politicians fill in the vacancies with the ritual murmur of transcendent abstraction foretelling the divine rescues to be achieved with “efficient cost controls” and “value-added purchasing,” with “tax exclusions” and “revenue incentives,” with the “public option” and “health-product procurement procedures” certain to come to pass in “the out-years” in Eden. Instead of raising awkward questions about the limits of medicine that acknowledge the inevitable rationing of medical care that inevitably will be perceived as both cruel and unjust, they discuss the positioning of decimal points, the relative value of this or that budget estimate, the cash flows to be drawn from low-income cooks and high-calorie sodas. They might as well be counting the number of angels that dance on the point of a syringe. If the committee chairmen were to sing the liturgy in Latin, a dove might descend from the Capitol dome and a unicorn step forth from the Lincoln Memorial, their joint press conference announcing the passage of legislation (bipartisan, risk-free, baby soft) bestowing on every American citizen—young and old, rich or poor, black and white, the law-abiding and the criminally insane—the constitutional right to life everlasting.

Together with the steadily accumulating inventory of life-changing drugs, the voluminous additions to the body of medical knowledge have come at increasingly higher costs, which, in the 1970s, prompted the development of health maintenance organizations that placed the country’s medical profession in the hands of insurance companies. The new set of procedures inducted doctors into the service of a private enterprise designed to make and manage money, not care for sick people. Whether in the form of simple prescription or complicated surgery, treatment requires “pre-authorization” from a corporation seeking to lower its “medical-loss ratio” (i.e., to reduce the amount of money spent on the care of the patients) in order to improve the health of its profit margin and preserve the life of its stock price. The administrative staff welcomes penitents enjoying the prior benefit of perfect health and rules out the people apt to need help, a separation of the wheat from the chaff in line with the teachings of the Christian Church that equate illness with sin.

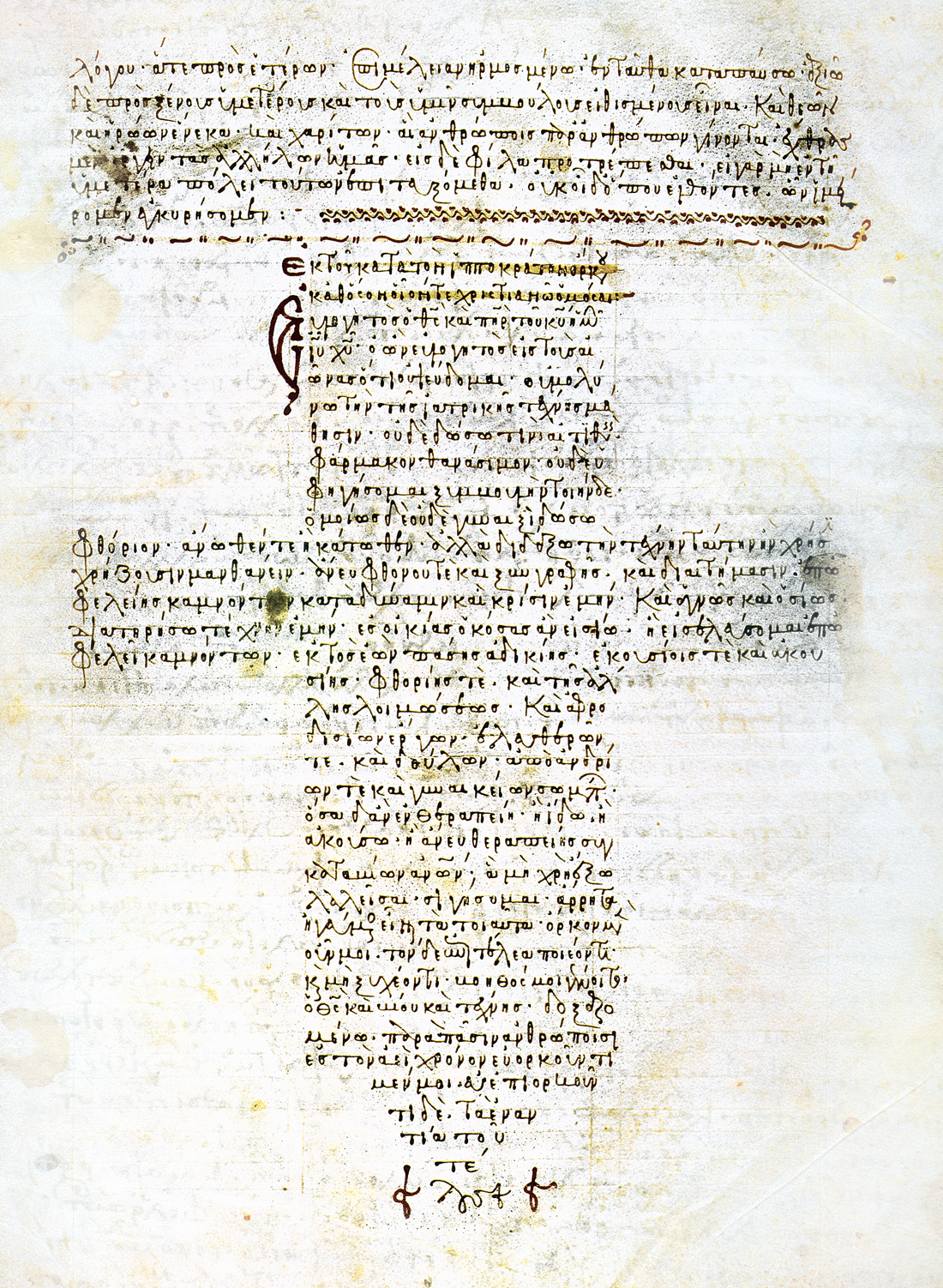

The Hippocratic Oath, Byzantine manuscript, twelfth century

The thirteenth century looked for saving grace in rose-colored stained glass; the twenty-first century looks for it in computer screens, our ultramodern medical techniques more in line with those of the Aztec priests who once marched their victims up the stone steps of the pyramid in the imperial city of Tenochtitlán, to the flaming braziers in which the still-living hearts were burned as offerings to Huitzilopochtli. Our own medical clergy, in keeping with the technological spirit of the age, supervise the ritual transfer of their patients to the dread deities housed in the sacred acronyms, to MRI, EGD, and EKG.

It isn’t that the country lacks for competent and caring doctors, but too many of them have been infected with the virus of the profit motive, overburdened with the ceremonial filling out of forms and the cost of the medications inoculating them against the catastrophic illness of a conviction for criminal malpractice. The “perplexed decompositions” added to the list of bankable diseases over the last twenty years (among them panic attack, bereavement, narcissistic personality disorder) have engendered the corollary expansion of the healthcare industry that now employs upward of fourteen million people in what has become the largest sector of the national economy. Like the military-industrial complex, the medical-industrial complex invites the practice of large-scale fraud, the hospital surcharges for an apple or an artificial limb comparable to the cost overruns paid by the Pentagon for a cruise missile or a wrench. The “waste” and “inefficiency” in the system is its bone and marrow. Of the $304 billion appropriation levied by the seven biggest pharmaceutical companies in 2007, $97 billion of the take was allotted to marketing and sales promotion ($27 billion in the form of free meals and drug samples given to attentive physicians), another $76 billion to payroll (earnings worth $29 million to the chief executive of Johnson & Johnson, $25 million to the chairman of Wyeth), lastly $40 billion (13 percent of the whole) to Research and Development.

The medieval church marketed its healthcare product as the forgiveness of sin, in the form of Papal indulgences intended to preserve the vitality of the immortal soul. In an age that places a higher value on the flesh than it does on the spirit, the guarantees on the label promise to restore the blooms of eternal youth. To the extent that we construe physical well-being as the most cherished commodity sold in the supermarkets of human happiness, we stand willing to spend more money on the warrants of longevity than we spend on lottery tickets and cocaine. Our consumption of medical goods and services constitutes the performance of what Thorstein Veblen in The Theory of the Leisure Class characterized as a devout observance—the futility and superfluous expense of the exercise testifying to its value as an act of worship. The more health product that we conspicuously consume, the more of us feel conspicuously ill. To express our devotion we magnify every “riddling distemper” the flesh is heir to, deprive ourselves of food and blood, discover diseases where none exist, incise ourselves with liposuction and the angiogram. The pharmaceutical companies step up the dosages of terror in their print and television advertising; volunteer committees of vigilance gather in city parks to keep a sharp watch for obese wastrels who neglect their aerobic exercises, smoke cigarettes, fail to ingest their antioxidants, refuse to drink their pomegranate juice. We learn to think, as do the characters in a Woody Allen movie, that we become commendable, or at least interesting, by virtue of the stigmata verifying our status as victims and attesting to our worth as patients.

The physician should look upon the patient as a besieged city and try to rescue him with every means that art and science place at his command.

—Alexander of Tralles, 600

Iain Bamforth’s essay finds a foreshadowing of the attitude in Thomas Mann’s novel The Magic Mountain. The precious invalids assembled in the sanatorium high up on a Swiss Alp look upon their therapies as stations of the cross, enduring their sorrows, as did the soon-to-be-ascending Christ, “with a sense of exaltation and even elation.” To the degree that the affluent American society as a whole imitates their refined example, “The magic mountain is no longer a retreat or social height; it is our everyday.”

Which isn’t to suggest that our doctors forswear the Hippocratic Oath, or that our politicians abandon hope of squeezing the pus out of the healthcare system. But where is the blessing to be found in the wish to live forever? A substantial fraction of the annual tithe collected by the medical-industrial complex is the invoice submitted ($528 billion) to payees in the last, often wretched, year of their lives. The corpses in waiting serve as sacrificial offerings placed on the altars of the god in the ATM. Plato thought it “shameful” to provide medical help “not for wounds or some seasonal illnesses” but because one “is filled with gases and phlegm, like a stagnant swamp, so that sophisticated Asclepiad doctors are forced to come up with names like ‘flatulence’ and ‘catarrh’ to describe one’s diseases.” Socrates in the dialogue with Glaucon compounds the argument with the observation that it is wrong to prolong lives no longer “profitable either to themselves or anyone else.” Medicine, he says, isn’t intended for such people, “not even if they are richer than Midas.”

I know that dying is un-American and nowhere mentioned in our contractual agreement with Providence, but absent some sort of renegotiation of the country’s arms-control treaty with death, I don’t know how we avoid dismembering the American body politic with the electromagnetic scalpels of our computer-generated fear. Any system that construes medical care as profit-bearing merchandise is by definition dysfunctional. The attempt to mark down the gifts of the human spirit to the measure of their weight in gold is an idiocy along the lines of the nineteenth-century attempt to cure tuberculosis by removing one lobe of an infected lung and filling the vacancy with ping-pong balls.