It is so long since I first took opium that if it had been a trifling incident in my life, I might have forgotten its date—but cardinal events are not to be forgotten, and from circumstances connected with it, I remember that it must be referred to as the autumn of 1804. During that season I was in London, having come thither for the first time since my entrance at college.

My introduction to opium arose in the following way. From an early age I had been accustomed to wash my head in cold water at least once a day; being suddenly seized with toothache, I attributed it to some relaxation caused by an accidental intermission of that practice, jumped out of bed, plunged my head into a basin of cold water, and with hair thus wetted went to sleep. The next morning, as I need hardly say, I awoke with excruciating rheumatic pains of the head and face from which I had hardly any respite for about twenty days. On the twenty-first day, I think it was, and on a Sunday, I went out into the streets, rather to run away—if possible—from my torments, than with any distinct purpose. By accident I met a college acquaintance who recommended opium. Opium! Dread agent of unimaginable pleasure and pain! I had heard of it as I had of manna or of ambrosia, but no further: how unmeaning a sound was it at that time! What solemn chords does it now strike upon my heart! What heart-quaking vibrations of sad and happy remembrances! Reverting for a moment to these, I feel a mystic importance attached to the minutest circumstances connected with the place and the time, and the man—if man he was—that first laid open to me the Paradise of Opium eaters. It was a Sunday afternoon, wet and cheerless—and a duller spectacle this earth of ours has not to show than a rainy Sunday in London. My road homeward lay through Oxford Street; and near “the stately Pantheon” (as Mr. Wordsworth has obligingly called it) I saw a druggist’s shop. The druggist—unconscious minister of celestial pleasures!—as if in sympathy with the rainy Sunday, looked dull and stupid, just as any mortal druggist might be expected to look on a Sunday; and when I asked for the tincture of opium, he gave it to me as any other man might do—and furthermore, out of my shilling returned to me what seemed to be a real copper halfpence, taken out of a real wooden drawer. Nevertheless, in spite of such indications of humanity, he has ever since existed in my mind as the beatific vision of an immortal druggist, sent down to earth on a special mission to myself. And it confirms me in this way of considering him, that when I next came up to London, I sought him near the stately Pantheon, and found him not—and thus to me, who knew not his name (if indeed he had one) he seemed rather to have vanished from Oxford Street than to have removed in any bodily fashion. The reader may choose to think of him as possibly no more than a sublunary druggist: it may be so, but my faith is better: I believe him to have evanesced, or evaporated. So unwillingly would I connect any mortal remembrances with that hour and place and creature that first brought me acquainted with the celestial drug.

Arrived at my lodgings, it may be supposed that I lost not a moment in taking the quantity prescribed. I was necessarily ignorant of the whole art and mystery of opium taking: and what I took, I took under every disadvantage. But I took it—and in an hour, oh heavens! What a revulsion! What an upheaving, from its lowest depths, of the inner spirit! What an apocalypse of the world within me! That my pains had vanished was now a trifle in my eyes—this negative effect was swallowed up in the immensity of those positive effects which had opened before me—in the abyss of divine enjoyment thus suddenly revealed. Here was a panacea—a φαρµακον νήπεvθες [soothing drug] for all human woes. Here was the secret of happiness—about which philosophers had disputed for so many ages—at once discovered: happiness might now be bought for a penny and carried in the waistcoat pocket; portable ecstasies might be had corked up in a pint bottle; and peace of mind could be sent down in gallons by the mail coach. But if I talk in this way, the reader will think I am laughing, and I can assure him that nobody will laugh long who deals much with opium—its pleasures even are of a grave and solemn complexion; and in his happiest state, the opium eater cannot present himself in the character of “L’Allegro”: even then he speaks and thinks as becomes “Il Penseroso.” Nevertheless, I have a very reprehensible way of jesting at times in the midst of my own misery, and unless when I am checked by some more powerful feelings, I am afraid I shall be guilty of this indecent practice even in these annals of suffering or enjoyment. The reader must allow a little to my infirm nature in this respect; and with a few indulgences of that sort, I shall endeavour to be as grave, if not drowsy, as fits a theme like opium, so antimercurial as it really is, and so drowsy as it is falsely reputed.

And first, one word with respect to its bodily effects, for upon all that has been hitherto written on the subject of opium—whether by travelers in Turkey (who may plead their privilege of lying as an old immemorial right) or by professors of medicine, writing ex cathedra—I have but one emphatic criticism to pronounce: Lies! Lies! Lies! I do by no means deny that some truths have been delivered to the world in regard to opium: thus it has been repeatedly affirmed by the learned that opium is a dusky brown in colour; and this, take notice, I grant; secondly, that it is rather dear—which also I grant, for in my time East India opium has been three guineas a pound, and Turkey eight; and thirdly, that if you eat a good deal of it, most probably you must do what is particularly disagreeable to any man of regular habits, viz., die. These weighty propositions are, all and singular, true; I cannot gainsay them, and truth ever was, and will be, commendable. But in these three theorems, I believe we have exhausted the stock of knowledge as yet accumulated by man on the subject of opium. And therefore, worthy doctors, as there seems to be room for further discoveries, stand aside and allow me to come forward and lecture on this matter.

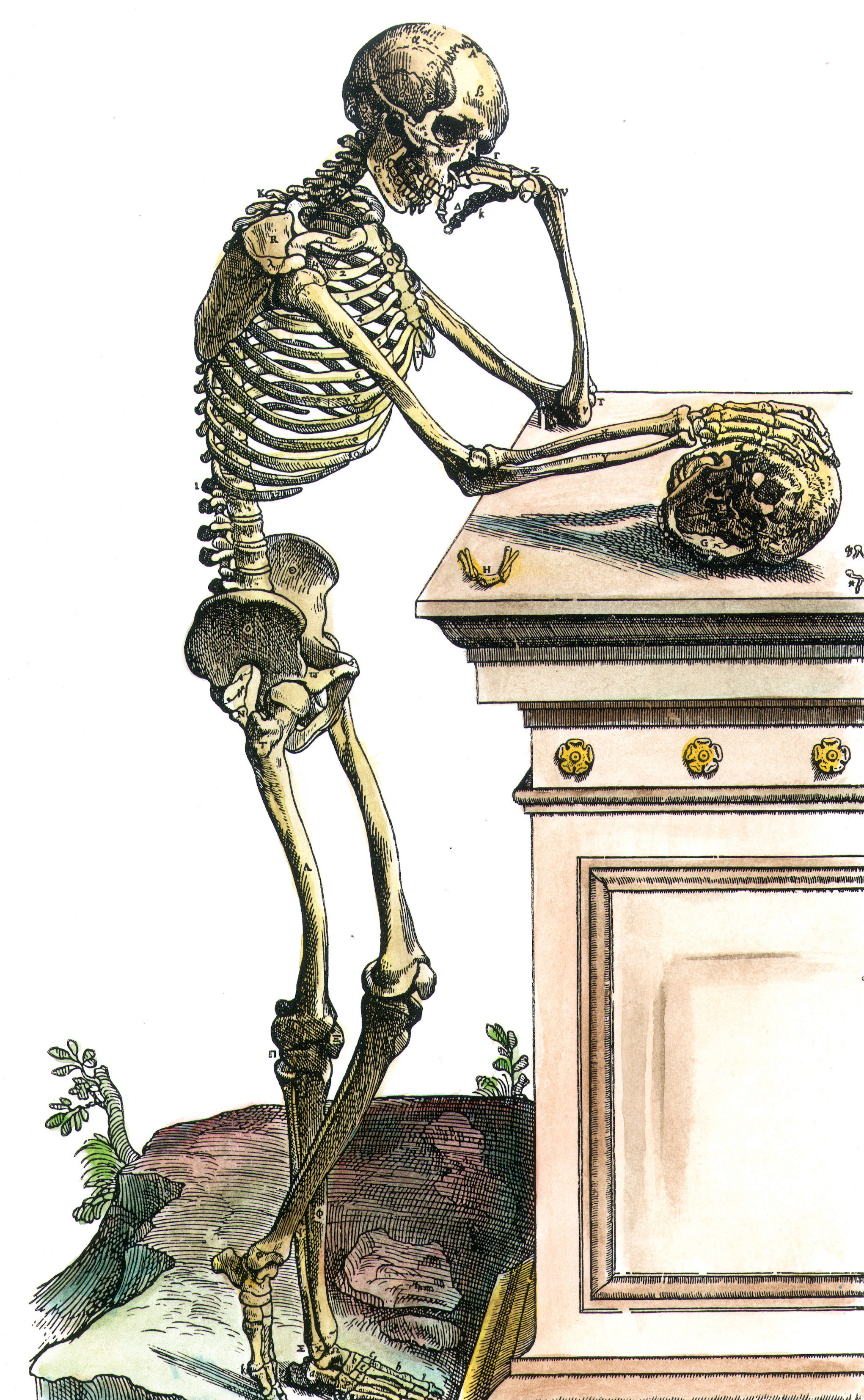

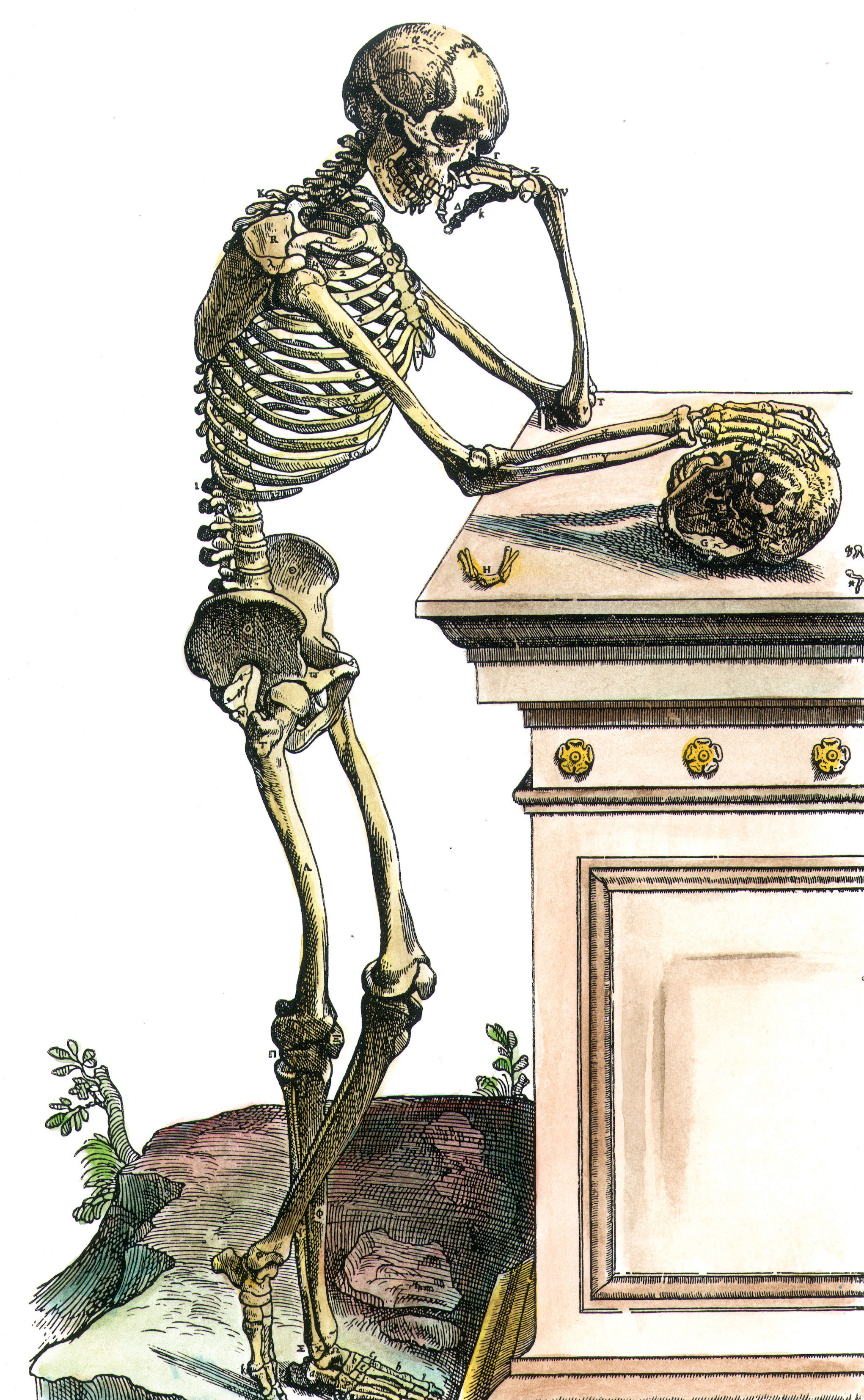

Skeleton contemplating a skull, from Andreas Vesalius’ On the Structure of the Human Body, 1543.

First then, it is not so much affirmed as taken for granted by all who ever mention opium formally or incidentally, that it does, or can produce, intoxication. Now, reader, assure yourself, meo periculo, that no quantity of opium ever did, or could, intoxicate. As to the tincture of opium (commonly called laudanum) that might certainly intoxicate if a man could bear to take enough of it, but why? Because it contains so much proof spirit, and not because it contains so much opium. But crude opium, I affirm peremptorily, is incapable of producing any state of body at all resembling that which is produced by alcohol—and not in degree only incapable, but even in kind; it is not in the quantity of its effects merely, but in the quality, that it differs altogether. The pleasure given by wine is always mounting and tending to a crisis, after which it declines; that from opium, when once generated, is stationary for eight or ten hours. The first, to borrow a technical distinction from medicine, is a case of acute; the second, of chronic pleasure—the one is a flame, the other a steady and equable glow. But the main distinction lies in this, that whereas wine disorders the mental faculties, opium, on the contrary (if taken in a proper manner), introduces among them the most exquisite order, legislation, and harmony.

Wine constantly leads a man to the brink of absurdity and extravagance, and beyond a certain point, it is sure to volatilize and to disperse the intellectual energies; whereas opium always seems to compose what had been agitated and to concentrate what had been distracted. In short, to sum up all in one word, a man who is inebriated, or tending to inebriation, is, and feels that he is, in a condition which calls up into supremacy the merely human—too often the brutal—part of his nature: but the opium eater (I speak of him who is not suffering from any disease or other remote effects of opium) feels that the diviner part of his nature is paramount—that is, the moral affections are in a state of cloudless serenity, and over all is the great light of the majestic intellect.

This is the doctrine of the true church on the subject of opium, of which church I acknowledge myself to be the only member—the alpha and the omega. But then it is to be recollected that I speak from the ground of a large and profound personal experience, whereas most of the unscientific authors who have at all treated of opium—and even of those who have written expressly on the materia medica—make it evident, from the horror they express of it, that their experimental knowledge of its action is none at all.

From Confessions of an English Opium Eater. Samuel Taylor Coleridge had written in his periodical, The Friend, that he wished to devote a work to the power of dreams; ten years later, his former friend De Quincey published his memoir, replete with descriptions of opium-induced dreaming. Virginia Woolf called the author “an exception and a solitary.” De Quincey as a literary critic is best known for his essay “On the Knocking at the Gate in Macbeth.”

Back to Issue