Well now, there’s a remedy for everything except death.

—Miguel de Cervantes, 1605Oath of Office

A conversation between Richard Selzer & Peter Josyph on the origins of the Hippocratic Oath.

By Richard Selzer

The Hippocratic Oath in Greek and Latin, published in Apud Andreae Wecheli heredes by Claudium Marnium, Frankfurt, 1595.

After more than thirty-five years teaching and practicing surgery at Yale University, Richard Selzer has for the last two decades pursued a second career as a writer of fiction and nonfiction, drawing on his long experience in medicine for the body of his work. Among his fifteen books are Mortal Lessons and The Doctor Stories, and two released this year, Knife Song Korea and Letters to a Best Friend, the latter a collection of letters with Peter Josyph. Peter Josyph is an artist, actor, and filmmaker, whose work includes the documentary Liberty Street: Alive at Ground Zero. This conversation was recorded in the winter of 1989.

Josyph: “I swear by Apollo, the physician.” On whom did Apollo practice?

Selzer: Well, he was called upon to heal miraculously. Iapyx, in the Aeneid, was a doctor. He had asked to learn the healing arts from Apollo because he wanted to save his own father, who was ill and dying. Famously, Iapyx was summoned to the battlefield because Aeneas was struck by an arrow, and Iapyx, who was unable to extrude the arrow, prevented an infection by treating the wound with an herb. Iatros, the word for doctor in Greek, is still used all over the world. Diseases that are caused by doctors are called iatrogenic diseases.

Josyph: Did Apollo minister to other gods?

Selzer: No, gods don’t need doctors. Actually, Asclepius was the god of medicine.

Josyph: “I swear by Apollo, the physician, and Asclepius.” Isn’t this the god that Socrates owed a cock to? Those were his last words, “Crito, we owe a cock to Asclepius.”

Selzer: Yes, and I remember seeing on a krater, one of those ancient pots, a painting of someone holding a cock and handing it to Asclepius. There was a Temple of Asclepius in Greece which was one of the most beautiful in the country, and it was there that sick people came from all over. They were told to lie down on pallets on a great veranda, called the abaton, outside of the temple. The priests would walk in bearing bowls of fire, and the patients were commanded to sleep. There were serpents—a species of large yellowish snake—that were given free run of the temple grounds. The patients were told that when they went to sleep in the temple they would dream, and in their dreams Asclepius would appear to them in the form of a serpent. So, that’s the way they were healed: they were healed by dreaming.

Now, science and technology—all of our medical advances—notwithstanding, I think that was a superior way to be healed—by a whole lot—than by going in and having, say, open heart surgery. The Greeks healed by dreaming! We’ve never reached those heights in medicine since. There are many testimonials by patients, carved into the stellae, these stone pillars, attributing their cures to this experience of being touched by the serpents in their dreams.

Josyph: The serpent in the Bible represents evil.

Selzer: Yes, but this is a good serpent. Finally the snake got the good role.

Josyph: Is there a lesson behind that dreaming business?

Selzer: There are great truths in it, frankly. Because the Greeks were not so entrenched in the Western scientific method that has hampered us, they were more open to the idea of mind-body unity, and they used it in healing.

Josyph: And by implication the individual’s ability to call upon the deeper forces of Nature?

Selzer: Yes—but of course they didn’t know that. They thought they were being healed by an act of the god. One had to propitiate this god and pray to him.

Josyph: They were right, though, weren’t they?

Selzer: They were absolutely right. There is no civilization like the ancient Greeks. That was the height of it. We’ve been going downhill ever since.

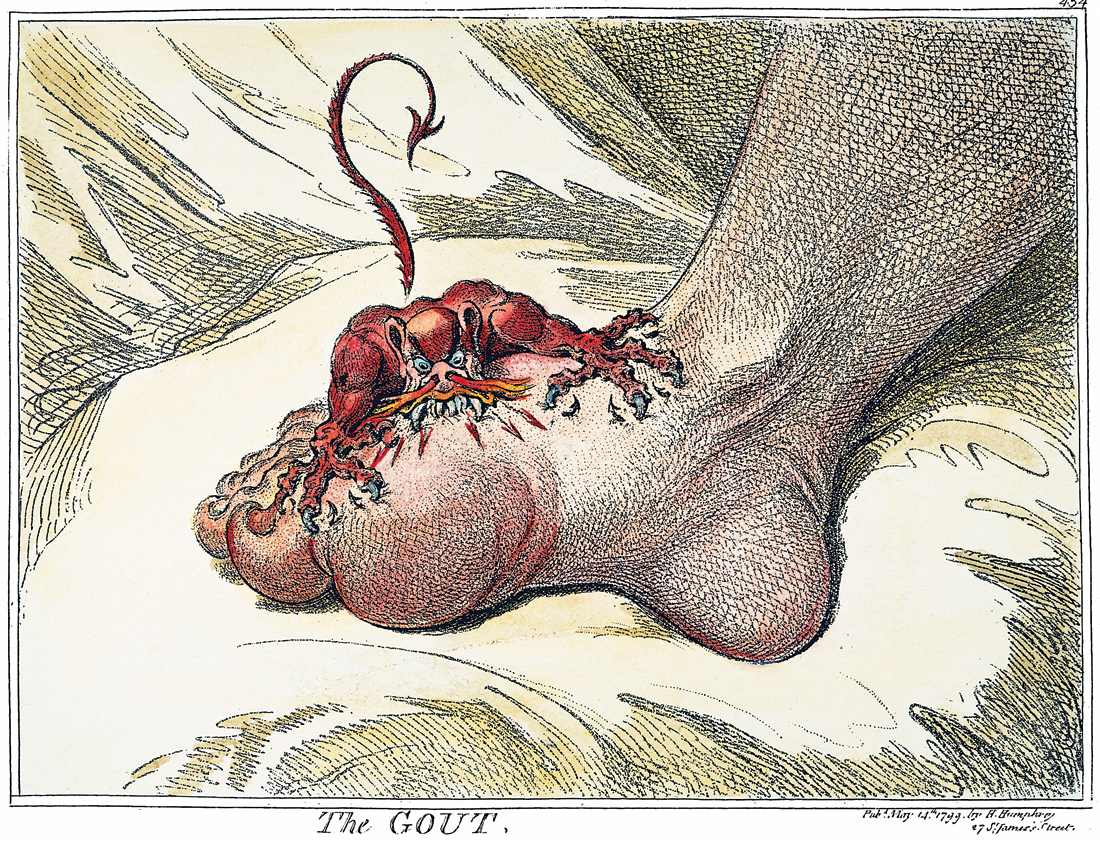

The Gout, etching by James Gillray, 1799.

Josyph: “To reckon him who taught me this Art equally dear to me as my parents.”

Selzer: Well, you see, this is a wonderful notion of the love between teacher and pupil, and the reverence in which the teacher was held by the pupil because of this gift he was giving. The transmission of the craft, the lore, to the next generation is an act of immense generosity and love. In our society this has virtually disappeared, hasn’t it? My own teachers of surgery were not, for the most part, reverable to me—and so, in a sense, I have broken the oath already, and it makes me very sad that I was not able to revere these men.

Josyph: The piety goes further. “To share my substance with him, and relieve his necessities if required.” That’s a beautiful phrase: to share my substance with him.

Selzer: Wealth, food, clothing, shelter.

Josyph: Not something young medical students are thinking about, is it? That at some point they should be willing to clothe, feed, house their former teachers?

Selzer: Not precisely, but it occurs to me—although I hadn’t thought this before—that by giving money, say, to your medical school, you might be reenacting this obligation.

Josyph: “To look upon his offspring on the same footing as my own brothers, and to teach them this Art—”

Selzer: “—if they wish to learn it, without fee or stipulation.”

Josyph: Is there anywhere that one can become such a student—without fee or stipulation?

Selzer: In this country? Heck no! But in Germany, for instance, medical school is free.

Josyph: But of course the teachers are paid. Here, as part of the oath, the one taking it will be willing to teach the offspring of his or her teacher for free.

Selzer: Yes, so that if my old professor of surgery’s grandchild wanted to become a surgeon, I would then teach him with no strings attached. The word doctor derives from the Latin doceo, meaning to teach—I teach—so that implicit in the title is the requirement that you pass it on.

Josyph: And yet you can impart your medical knowledge to your sons and to those of your teachers who will take this oath, “and to none others.”

Selzer: Because it was considered a sacred vocation—sacred, and a secret. We physicians and surgeons are the direct descendants of the shamans. They are our colleagues, the shamans, because they have the healing power. They descend into the underworld and bring back the wherewithal to heal their tribesfellows.

Josyph: Aristotle’s father was a physician, but Aristotle, learned as he was, wasn’t a doctor—so it wasn’t a requirement that you pass this knowledge down?

Selzer: No, but I think that it was likely, in the same way, for example, that the marvelous artisans of Japan—who are actually termed living national treasures, these old men, because they can do one thing better than anyone else in the world—perhaps it’s weaving, or playing a musical instrument, or making swords—it is traditional that these arts are passed on from father to son to grandson, so that a particular family is associated with this. In India, where they have very gifted bonesetters, the lore was handed down within the family. It still is.

It’s interesting that people tend to lump law and medicine together as the professions. Nothing could be farther from the truth. Lawyers have clients, doctors have patients. The word client comes from the Latin cliens, clientis, a feudal serf who lived on the land of the lord and had to pay for protection, so that a client is someone for whom a service is employed. The word patient derives from the Latin patior, pati, meaning to suffer. Patients are not clients: they are people in pain. It’s a different concept entirely.

Josyph: In the Law of Hippocrates, he says that a natural talent is required for one to become a student of medicine. We tend to think of talent as more related to art, and yet Hippocrates himself refers to medicine as an art.

Selzer: Yes. The people who go to medical school are those who want to go, whether they have the talent or not. It seems to me there is danger in that. If we chose our airline pilots with the same carelessness, think of the carnage that would ensue! The medical profession ought to police itself better. Those who show no talent ought to be weeded out, advised against it. It would be a service to them too, although they would not feel it at the time. They should be dissuaded from being let loose on the populace. It’s very difficult, once a person is halfway through his or her surgical training, to say, “Look, you don’t really belong in this business.” It is rarely done. One feels sympathy for this man or this woman who has a wife or a husband and two little children and is laboring to get through this training. That’s all well and good—sympathy is a virtue—but, when you think of the consequences to the legions of people who will fall prey to this person in the future, then you must temper your sympathy, harden your heart, and say no. Of course the training is rough. The way it’s taught is appalling. There are years of memorizing, by rote, partly unnecessary materials, followed by years of deprivation of sleep, rest, and leisure. It’s no wonder there is no more depressed group of students.

Some people have no interest or ability to teach medicine. They should not be engaging in it. Only those who love to impart knowledge, to pass it on, ought to do that work. I loved teaching surgery. It’s like teaching nothing else. There is a living patient lying between the teacher and the pupil. It’s a marvelous event, because the four hands move above and literally within the human body of a third person, always in contact with each other. The teacher must restrain his pupil before harm should have come to the patient for whom he is acting in loco parentis. And yet he must give rein to the pupil so that he will learn to do these things. It is a very delicate balance between reining in and giving permission to act. And of course above these four hands are the two voices murmuring to each other. “Is this how you do it?” “No, no—do it this way—here, I’ll show you. Now you do it”—that kind of thing. It is a murmuring, tactile pedagogy that cannot be duplicated in any other form of instruction, because of the presence of the third person. The material upon which you work is the living human body. As Emily Dickinson said, “Surgeons must be very careful/When they take the knife!/Underneath their fine incisions/Stirs the culprit—Life!”

Josyph: What about, “I will give no deadly medicine to anyone if asked”? Is that against mercy killing?

Selzer: It is interpreted by many people as just that, but there is debate about it. I think that what Hippocrates meant had nothing to do with euthanasia, but giving poison to someone for them to kill someone else.

Josyph: “I will not give to a woman a pessary to produce abortion.” That’s pretty clear, isn’t it?

Selzer: Except that a pessary doesn’t induce abortion. A pessary is inserted into the cervix—the mouth of the uterus—to prevent conception. Also, if the womb has fallen or dropped from too many childbirths, a pessary can act as a splint to hold the uterus in place. That sentence is always wondered about. Perhaps in those days pessary meant something different than it does to us now.

Josyph: Is it in the oath today?

Selzer: Some of the oaths that I have read recently are modified and modernized.

Hand with boils, from An Inquiry into the Causes and Effects of the Variolae Vaccinae, by Edward Jenner, 1798. The Wellcome Library, London.

Josyph: Well there is this that I found, which has had all the juice and the spirit taken out of it—it’s called the Declaration of Geneva. “I solemnly pledge myself to consecrate my life to the service of humanity.” No mention of the gods, of Panacea, of Asclepius. “I will give to my teachers the respect and gratitude which is their due; I will practice my profession with conscience and dignity.”

Selzer: Yes, it’s watered down and with the mythology taken out of it. We’ve cut ourselves off from our myths. It’s our rashest act. If man cuts himself off from the myths that surround him, and in which are embedded the seeds of his origins, he does so at great risk. It’s really devoid of sanctity, piety, and in its place there is a kind of cynicism. If one needs to make allowances for all the changes in our world, I would prefer the original Hippocratic Oath to be given—the one that I took—and have it interpreted in a more figurative way.

Josyph: “I will not cut persons laboring under the stone, but will leave this to be done by men who are practitioners of this work.” Does that mean that for a general practitioner there should be no surgery?

Selzer: I think that what the oath is putting forward here is that a doctor should do only that which he is capable of doing. The stone was a very common condition, particularly in men. Before you could remove a prostate gland and therefore open the exit of the bladder for urination, these people had stagnation of urine in their bladders and the salts in the urine settled and concretized. They adhered to each other and formed a stone that grew to be quite large and would block off the opening of the urethra. This is what Montaigne suffered from. Ben Franklin had bladder stones, and Ben Franklin being Ben Franklin, he invented a catheter and made it out of metal. When his bladder stones got painfully large, he would take this little metal catheter and insert it up the bladder, dislodging his stone and allowing for urination. He made one for his brother, who also had bladder stones, and one for himself. Samuel Pepys, in his diary, mentions his own operation, being cut of the stone. It was performed at his cousin Jane’s house. Poor little Pepys! He was a tiny little man, and with all these people holding him down, the surgeon cut for stone. The operation had to take no more than thirty seconds because it was done without anesthesia. They cut you between the scrotum and the rectum because that was the shortest distance to the bladder. They’d hold your legs up, the surgeon would make the cut, then fish out the stone. Then they would tie your legs together, which is how they controlled the hemorrhage. When Pepys had his operation he joined that elect band of men—mostly men, but some of them were women—who had their bladder stones. They were given their bladder stones to keep. They had not only survived: they had their stone, and some of them were really quite marvelous. Pepys had a beautiful, elaborately carved box made to display his. It was like a club of these people who could meet and show each other their bladder stones.

Let me recommend the best medicine in the world: a long journey, at a mild season, through a pleasant country, in easy stages.

—James Madison, 1794Josyph: “Into whatever houses I enter, I will go into them for the benefit of the sick and will abstain from every voluntary act of mischief and corruption, and further, from the seduction of females or males.”

Selzer: Which is, of course, essential. It’s the basis of medical ethics, that a doctor shall not satisfy his lust on his patients. If the doctor, who is privileged to observe the nakedness of people and to touch their bodies, were to think of them in terms of sexuality, it would be unpardonable. It is the single insupportable fact. One of the most trying things for medical students when they first examine the bodies of other people is that they cannot control their lust. They are assailed by lust, and it is necessary to put that aside. That takes time. They are made very uncomfortable by that. There is guilt, because they think, “What kind of person am I?” It’s like the priesthood: a priest must subdue and conquer his lust. I’m sure there are doctors who have lusted in their heart, but of course this must never be acted upon.

Josyph: “Whatever in connection with my professional practice … I see or hear … which ought not to be spoken of abroad, I will not divulge.” Have you found that to be true?

Selzer: No, it’s not true at all. I had a personal encounter with that, which I should not like to repeat. An ostensible friend and colleague of mine was the doctor of someone who is related to me. This doctor spread abroad, in the community, something this person had told him. When I heard this and tracked it down, I called him and quoted from the Hippocratic Oath.

Josyph: That’s exactly what it’s meant to guard against—it’s like with a Catholic confessor, almost a sacred trust.

Selzer: Yes, and he violated that. Naturally that man and I—

Josyph: —severed relations?

Selzer: Yes. Permanently.

Josyph: The oath itself expects that kind of punishment. “While I continue to keep this Oath unviolated, may it be granted me to enjoy life and the practice of the Art … But should I trespass and violate this Oath, may the reverse be my lot.”

Selzer: That’s a wonderful way of putting it, is it not? It’s really a prayer: Punish me if I do not adhere to this oath. Don’t let me off scot-free; may my conscience bother me, may I be made miserable if I break these promises.

Josyph: Is it true that in ancient China you paid your physician when you were well and ceased paying when you were sick?

Selzer: [laughing] I wonder if it’s really true! It’s a nice idea. In Mark Twain’s autobiography he talks about medicine in his little town of Florida, Mo., where you paid the doctor a yearly sum of twenty-five dollars and never paid him again—and for that he took care of your family for a year.

Josyph: I wonder whether it was worth that much? Speaking of that: why were barbers in charge of surgery?

Selzer: You also went to the barber to be bled—they were the venesectors. Surgeons were considered to be a lesser breed of physicians. They were not called doctors. To this day in England a surgeon is called Mister because it was a lesser breed. Barber-surgeons were seen as nonprofessionals who knew how to do this one thing, and it was one of the few things that you could do—you could bleed, or you could purge people with physic, from which we derive the word physician. And you could amputate a limb. It was a therapy of subtraction. After that there was just the priest.

Josyph: Finally, from the Law of Hippocrates, there is this: “Those things which are sacred are to be imparted only to sacred persons.”

Selzer: If we imparted knowledge only to sacred persons there wouldn’t be a single doctor alive in this world!

Josyph: It’s a broader meaning of sacred?

Selzer: Yes, and that you become sacred by having been initiated into the mysteries of science. The mantle of sacredness descends upon you with the learning, and then you are initiated into the mysteries of the priesthood.

Josyph: For a medical student who is about to graduate, what is it like to take the Hippocratic Oath?

Selzer: It’s very moving to me. I have taken part in many medical school commencements as the speaker or as an honorary degree recipient. At one point the member of the faculty who has been designated to administer the oath goes to the podium and asks the graduates to rise. They do, and I rise also because I want to take it again, to renew it, as it were.

Josyph: That must be some sound, all those physicians making these solemn promises.

Selzer: It is, and it’s a wonderful occasion. It’s a connection with our past, with our origins. I revere it.

Josyph: Not such a bad fellow, Hippocrates.

Selzer: No, he was a good guy.