He who is afraid of his own memories is cowardly, really cowardly.

—Elias Canetti, 1954

Plate 4 of Visions of the Daughters of Albion, by William Blake, c. 1795. Photograph © Tate (CC-BY-NC-ND 3.0).

Audio brought to you by Curio, a Lapham’s Quarterly partner

There is no language chaste enough for the death of one we love. We ache to keep alive not only a life shared but also the totality of our loved one’s inner life—how they thought, how they listened, what was at stake—and not only our sense of this inner life but the countless ways they belonged to their time and place. And for generations dominated by war and, increasingly, in this world of dislocation and dispossession, where so many do not die in the place where they were born—to honor the complexity and meaning of their exile.

History makes us fear for our moral soul. There is nothing a man will not do to another, nothing a man will not do for another. We must personalize what history depersonalizes. What does it mean when one’s most private, most profound experience, the cataclysm that shapes one’s life, is also the most intimate experience of thousands of others—battle, siege, ghetto, refugee camp? What place can be found for our private grief when set against the losses of entire nations? Labor migration, political exile, climate exile, mass dispossession of every kind. Where do we belong? Where we are born or where we are buried, where our children are born, where we are abandoned, where we are wounded, where we are rescued. Where love finds us.

During the First World War, soldiers learned to keep a Bible in the breast pocket of their uniform. Not for solace but because it was a book thick enough to stop a bullet. Perhaps, after all, a kind of solace.

Stories told on a battlefield, on a life raft, in a hospital ward at night. In a café that will disappear before morning. Someone overhears. Someone listens, attentive with all his heart. No one listens. The story told to one who is slipping into sleep, or into unconsciousness, never to wake. The story told to one who survives, who in turn will tell that story to a child who will write it down, to be read by a woman in the middle of the night, hooked to a dialysis machine in a hospital fifteen thousand miles away, who will recognize something essential in herself.

Sunday evening, winter morning, April dusk. Waking in a room so dark with rain we thought it was night. Grief, loss, regret are not the end of the story. They are the middle of the story. Memory does not look backward, it looks forward.

In 1944, in Warsaw, German soldiers scrawled numbers on the buildings in white paint and then systematically demolished the city, while the Soviet army watched and waited across the Vistula. After the war, the Poles returned to Warsaw and, living in the rubble, began to rebuild. Devastated cities across Europe faced the same choices. Should the ruins be left in view, like the cathedral at Coventry, with new buildings erected beside them, a permanent memorial? Should the rubble (with its dead) be hidden and a new, modern city built on top of it? Or perhaps, as the Poles decided, the old city should be replicated, rebuilt in the same place, in every last detail—every cornice, lamppost, and windowsill—an act of defiance and despair, the fiercest response to the fact that we can’t bring back the past, we can’t bring back the dead. In this replication was a kind of terror—the calling forth of spirits and the speaking aloud of a harrowing, unanswerable doubt: that the replica might erase precisely what it was meant to memorialize.

In the 1950s, in Canada, during the building of the St. Lawrence Seaway, towns and villages on the floodplain along the St. Lawrence River were permanently evacuated. The Hydro-Electric Power Commission of Ontario offered to move people’s houses to newly constructed towns, using the mighty Hartshorne House-Mover. Houses left behind were set afire. The commission also offered to move the bodies from the graveyards that would be flooded. Most people chose to respectfully leave the dead where they were. For decades after, people refused to swim in the river for fear of the dead rising into the water. The sidewalks and stone foundations of those towns can still be seen, floating ghostly below the surface of the river.

In the 1960s, in Egypt and Sudan, during the building of the Aswan High Dam, almost the entire nation of Nubia was dispossessed and relocated, while the Nubian homeland disappeared under one of the largest man-made lakes in the world. Countless archaeological sites were flooded. The colossal Abu Simbel temples were saved from floodwaters by a UNESCO initiative, the entire site dismantled, each stone block numbered and, ton by ton, transported two hundred feet higher, where the temples were reassembled and the surrounding landscape impeccably reproduced. This feat of engineering created an illusion, a deceit so perfect it was a betrayal; if one could be fooled into believing one stood on the original site, then Abu Simbel, reerected for a new purpose, was no longer sacred.

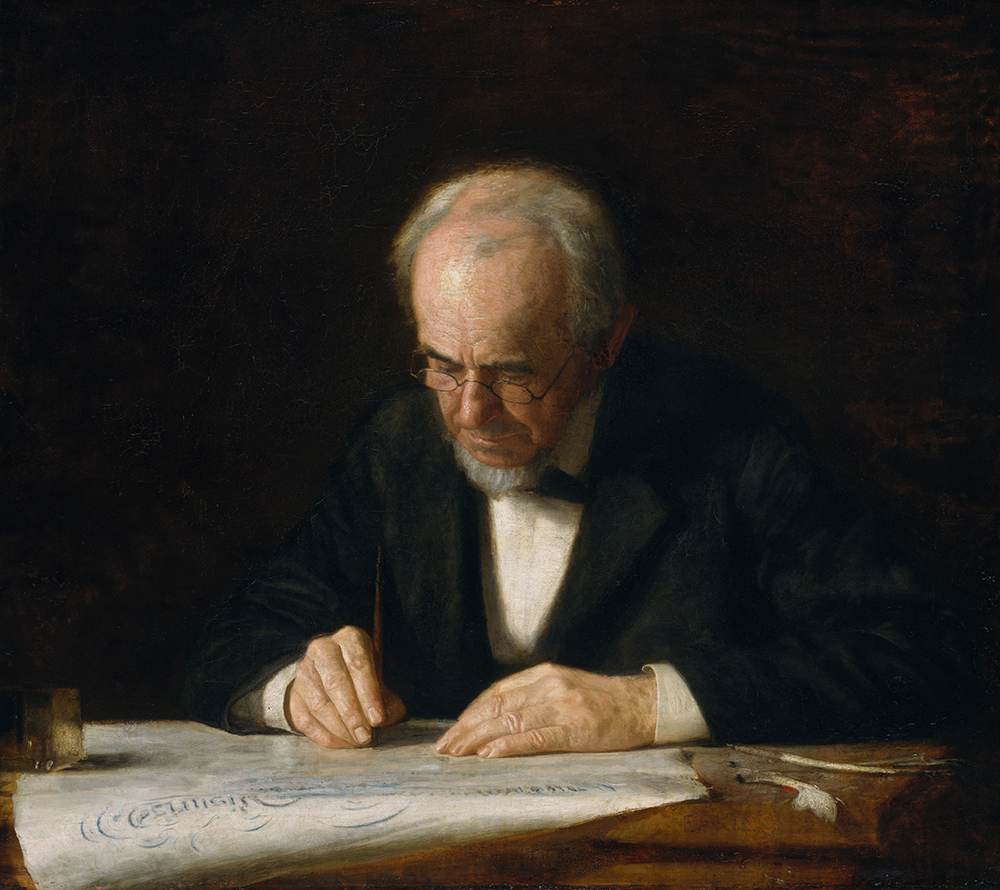

The Writing Master, by Thomas Eakins, 1882. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, John Stewart Kennedy Fund, 1917.

The Nubians would never be able to return to their homes, their land, their landscape, on the banks of the Nile. But more than this, their flooded homeland had vanished from the face of the earth. In other times and other places, people had lost their homeland while they slept, lying down in one country and waking in another, without even rolling over in their beds, borders redrawn and countries renamed in the night.

What we carry when we are forced to leave everything behind is language, memory, our bodies. To consider how we remember privately and how we memorialize publicly, as a community or a country, to consider the difference between personal grief and historical grief, is to seek to understand history’s enduring deceptions, replication and renaming, the visible lie and the invisible truth, the visible truth and the invisible lie. Memory haunts the ruins of history, seeking meaning.

Literature carries the living and the dead. It binds to love, to profound transformation, it clings to places of shame, it pools in places of invisibility, regret, catastrophe; it clings to conscience. But art is not self-expression, it is the expression of what is beyond the self.

Literature strives for something beyond grasp. A lesser work, which strives for less and achieves its lesser goal, is not alive in the same way—it manipulates and is derivative of experience rather than in confrontation with it; and without that engagement, where everything is at risk for both writer and reader, it is not generative. And this lesser art, like a simulacrum, will never be central to our desire. In a similar way, in the privileged places of the world, appetite can be seen as a substitute, a simulacrum of hunger.

How do we discern between what it original and what is simulated? The work of the simulator is more deplorable than the forger, who acknowledges the value of the original rather than erases it by imitation. That is why the cheap plastic flower, roughly produced, is more real than the sophisticated imitation that fools us into thinking it is real. The first does not pretend to be real, does not pretend to be what it is not, and consequently reminds us, ensures we remember, what is real. The entire intention of the second is to deceive us, to make us forget what is real. It seeks to replace what is real.

Reproduction consists of the old and new. The forger uses pigment and materials that date from the time of the original. Simulation consists only of the new. Warsaw was reconstructed using drawings, paintings, and other visual records, as well as a mix of original stonework and relocated stone. New trees grew where old trees had stood. Small changes were made to accommodate modern use, but visually the old city rose from its debris, a remarkable achievement of backbreaking labor and resolve, and a powerful statement addressing Soviet intentions.

The Veteran in a New Field (detail), by Winslow Homer, 1865. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Bequest of Miss Adelaide Milton de Groot (1876–1967), 1967.

In Warsaw the impulse to systematically replicate what was systematically destroyed was an act of confrontation with history, not refutation. As survivors entered the re-created streets, they were in direct confrontation with both the past and the future. Here was a place for both the dead and the living. The re-created city stood for democratic statehood—and even this symbol was both old and new, for now it was a statehood that had survived near obliteration.

Nothing enrages the tyrant more than hope. Inherent in reconstruction after the Second World War was not only the desire to remember the dead but also the hope that the dead would remember us. To assert that we had not lost our humanity, that we, and the world, after such depravity, might still be morally recognizable.

Now, a little more than half a century later, we have created a technology that leaves no place for the dead. It is a realm of perpetual present, a realm of simulation, where the past is as fluid as the future. Deepfake, the technology that uses machine learning to create highly realistic false videos, can re-create its subject even posthumously. It can cause us to remember what never happened. No longer will we have any assurance that we are remembering the dead. And the dead will no longer remember us—we will have become unrecognizable.

Erasure of figures from photographs—a favorite tactic of Stalin—now seems archaic in its reach and was primarily focused on the past. The deepfake can corrupt on a scale of such magnitude that its reach is timeless. It can falsify past, present, and future, creating and inferring events that will never occur, yet will hover in the air like a prophecy. Even a black hole becomes apparent by bending the proximate space. A deepfake, especially as technology continues to magnify its power, will continue to elude our perception and soon will leave no trace of its powers of distortion, though it will certainly contort the moral space around it. As always, the consequences of technology are a result not of the technology itself but of our laws and our will. Every deception erodes our will.

Anything one is remembering is a repetition, but existing as a human being that is being, listening, and hearing is never repetition.

—Gertrude Stein, 1935The deception of the deepfake requires hundreds of photographs of its subject and will require fewer as the technology improves. Perhaps we will revert to the handmade portrait to represent ourselves; perhaps, publicly, we will hide our faces.

Recently a time capsule was embedded deep in the ice of Antarctica. The depth and location of the capsule were carefully calculated—as precisely as possible in the present state of our rapidly shifting climate. Inside were letters to the future. To write such a letter was a precipitous fall into space-time. Not to be opened for one thousand years. Even after one hundred years, the wisest and most conservative conjecture dissolves into fantasy. Writing into the future can only produce a form of memory.

In Antarctica a human voice—depending on air temperature, wind direction, the quality of the ice to refract sound—can be heard almost two miles away. There are few places of such silence on this earth. But there are other ways, if we have the desire and the will, to hear voices from a distance, even when that silence is gone. And it can still be found in our communion with literature, with art—a deep privacy that is simultaneously the voice of one mind, one soul, to another. There is no redemption in history. The dead remain where they are buried. But memory knows that the dead will float to the surface of the river. Memory knows the dead can read.

In your hands, my hunger.