A society that has more justice is a society that needs less charity.

—Ralph Nader, 2000Edifice Complex

There’s no such thing as a free library.

“Has Andrew Carnegie given you a library yet?” asked Mr. Dooley.

“Not that I know of,” said Mr. Hennessy.

“He will,” said Mr. Dooley. “You’ll not escape him. Before he dies he hopes to crowd a library on every man, woman, and child in the country. He’s given them to cities, towns, villages, and whistling stations. They’re tearing down gas-houses and poorhouses to put up libraries. Before another year, every house in Pittsburgh that ain’t a blast furnace will be a Carnegie library. In some places all the buildings are libraries. If you write him for an autograph he sends you a library. No beggar is ever turned empty-handed from the door. The panhandler knocks and asks for a glass of milk and a roll. ‘No, sir,’ says Andrew Carnegie. ‘I will not pauperize this unworthy man. Nothing is worse for a beggar man than to make a pauper out of him. Yet it shall not be said of me that I give nothing to the poor. Sanders, give him a library, and if he still insists on a roll tell him to roll the library. For I’m as humorous as well as wise,’ he says.”

“Does he give the books that go with it?” asked Mr. Hennessy.

“Books?” said Mr. Dooley. “What are you talking about? Do you know what a library is? I suppose you think it’s a place where a man can go, haul down one of his favorite authors from the shelf, and take a nap in it. That’s not a Carnegie library. A Carnegie library is a large, brownstone, impenetrable building with the name of the maker blown on the door. Library, from the Greek word libus, a book, seldom—seldom a book. A Carnegie library is architecture, not literature. Literature will be represented. The most celebrated dead authors will be honored by having their names painted on the wall in distinguished company, as thus: Andrew Carnegie, Shakespeare; Andrew Carnegie, Byron; Andrew Carnegie, Bobby Burns; Andrew Carnegie, and so on. Every author is guaranteed a place next to pure reading matter like a baking powder advertisement, so that when a man comes along that never heard of Shakespeare he’ll know he was somebody, because there he is on the wall. That’s the dead authors. The live authors will stand outside and wish they were dead.

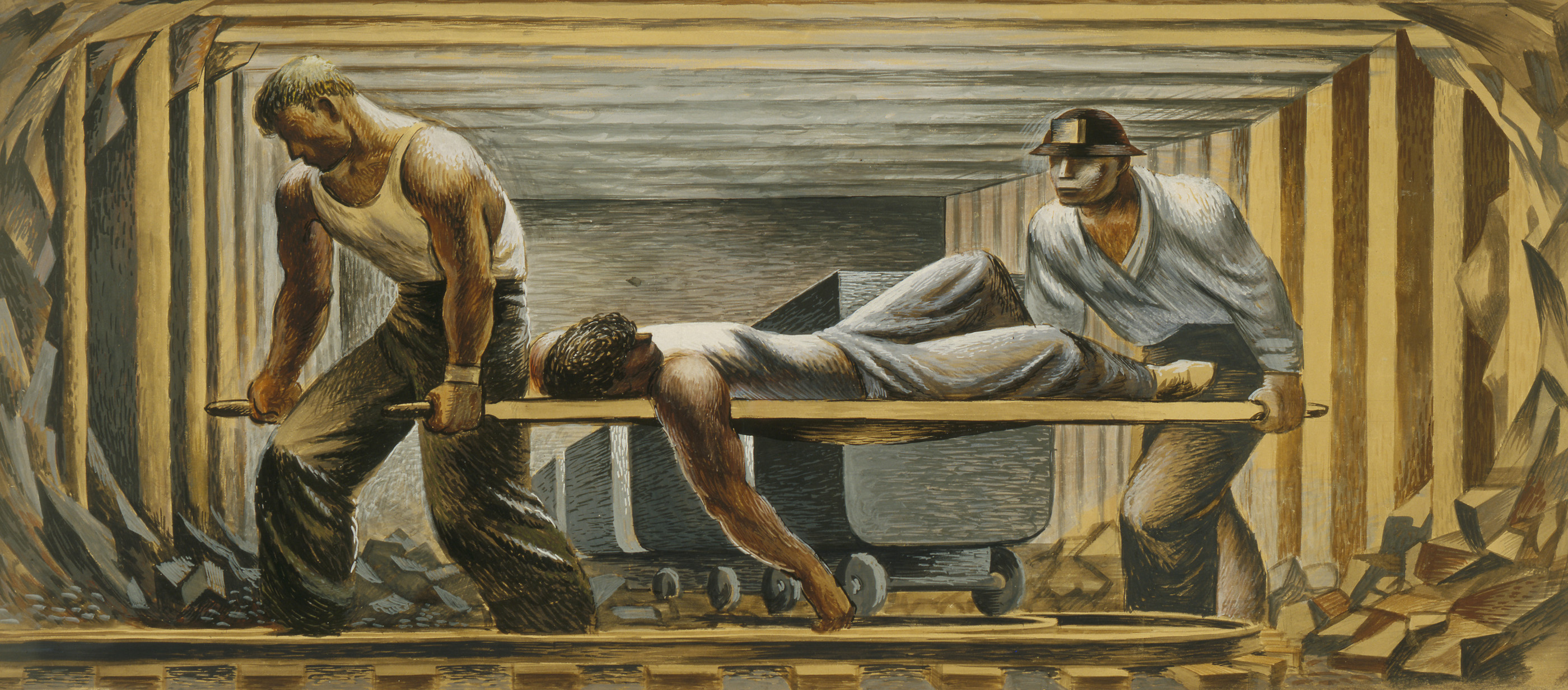

Mine Rescue, by Fletcher Martin, 1939. Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, DC.

“Libraries never encouraged literature anymore than tombstones encouraged living. No one ever wrote anything because he was told that a hundred years from now his books might be taken down from a shelf in a granite sepulcher and someone would write ‘Good’ or ‘This man is crazy’ in the margin. What literature needs is filling food. If Andrew would put a kitchen in the libraries and build some bunks or even swing a few hammocks where living authors could crawl in at night and sleep while waiting for this enlightened nation to wake up and discover the Shakespeare now on the turf, he would be giving a real boost to literature. With the smoke curling from the chimney, and hundreds of poets sitting around a table loaded down with pancakes and talking poetry and prizefighting, with hundreds of other poets stacked up nightly in the sleeping rooms and snoring in one grand chorus, with their wives holding down good-paying jobs as librarians or cooks, and their happy little children playing through the marble corridors, Andrew Carnegie would not have lived in vain. Maybe that’s the only way he knows how to live. I don’t believe in libraries. They pauperize literature. I’m for helping the boys that are now on the job. I know a poet on Halsted Street that once wrote a poem beginning, ‘All the wealth of India,’ that he sold to a magazine for two dollars, payable on publication. Literature doesn’t need advancing. What it needs is advances for literature. You can’t shake down posterity for the price.

“All the same, I like Andrew Carnegie. Him and me are agreed on that point. I like him because he isn’t ashamed to give publicly. You don’t find him putting on false whiskers and turning up his coat collar when he goes out to be benevolent. No sir. Every time he drops a dollar it makes a noise like a waiter falling down stairs with a tray of dishes. He’s giving the way we’d all like to give. I never put anything in the poor box, but I would if Father Kelly would rig up like one of those slot machines, so that when I stuck in a nickel my name would appear over the altar in red letters. But when I put a dollar on the plate I get back about two yards and hurl it so hard that the good man turns around to see who done it.

“Do good by stealth, says I, but see that the burglar alarm is set. Any benevolent money I hand out I want to talk about me. Him that giveth to the poor, they say, lendeth to the Lord. But in these days we look for quick returns on our investments. I like Andrew Carnegie and, as he says, he puts his whole soul into his work.”

“What’s he mean by that?” asked Mr. Hennessy.

“He means,” said Mr. Dooley, “that he’s generous. Every time he gives a library he gives himself away in a speech.”

Finley Peter Dunne

"The Carnegie Libraries.” In 1892 Dunne began contributing Irish-dialect sketches to the Chicago Evening Post, ultimately publishing more than seven hundred. His best-known character was Mr. Dooley, a South Side saloonkeeper who held forth on various political and social follies. “One of the strangest things about life,” he wrote as Mr. Dooley, “is that the poor who need the money the most are the ones who never have it.” Dunne died in New York City in 1936.