The day passes, the evening comes, and Franks and pagans fight on with their swords. Those who have led these two hosts into battle are brave men. They have not forgotten their war cries—the emir, Baligant, shouts, “Precieuse!” and Charles raises his famous battle cry of “Mountjoy!” And by their clear ringing voices the two men recognize each other, and they meet in the middle of the field and ride to attack each other, and exchange heavy blows, each one’s spear smashing into the other’s ringed shield. And each shield is pierced above the broad boss, and the folds of both of their hauberks are rent, but on neither side do the spears enter the flesh. Their cinches break and their saddles tip over and both kings fall to the ground, but they leap to their feet at once and bravely draw their swords. Now nothing can separate them, and the fight cannot end except with the death of one or the other.

Charles of sweet France is gifted with great courage, and the Emir shows neither dread nor hesitation. They draw their swords, showing the naked blades, and they deal each other heavy blows on their shields, cutting through the leather coverings and the two outer layers of wood, so that the nails fall and the buckles are broken in pieces. Then, bare of shields, they hack at each other’s coats of mail, and the sparks leap from their bright helmets. This combat cannot be brought to an end without one or the other confessing that he is in the wrong.

The emir says, “Charles, consider the matter carefully and make up your mind to repent for what you have done to me. You have killed my son, if I am not mistaken, and you are wrongfully disputing with me the possession of my own country. If you will become my vassal and swear fealty to me, you may come with me and serve me from here to the East.”

Charles answers, “To my way of thinking that would be vile and base. It is not for me to render either peace or love to a pagan. Submit to the creed which God has revealed to us, become a Christian, and my love for you will never end as long as you put your faith in the omnipotent King and serve Him.”

Last Supper, by El Greco, c. 1567-70. National Art Gallery of Bologna, Italy.

Baligant says, “You have begun a bad sermon!” Then they raise their swords and resume the fight.

The emir is a strong and skillful fighter. He strikes Charlemagne upon his helmet of burnished steel and splits and smashes it above his head, bringing the sword down into the fine hair, sheering off a palm’s breadth and more of flesh, and laying bare the bone. Charles staggers and almost falls, but it is not God’s will that he should be killed or beaten. St. Gabriel comes to his side, asking, “Great king, what are you doing?”

When he hears the holy voice of the angel, Charles loses all fear of death, and his vigor and clearness of mind return. He strikes the Emir a blow with the sword of France, cleaves the helmet flashing with jewels, cuts open the head and spills the brains, and splits the whole face down through the white beard. It is a corpse, past all hope of recovery, which that stroke hurls to the ground. Charles calls “Mountjoy!” to rally his vassals, and at his shout Duke Naimes comes to him bringing with him the Emperor’s horse Tencendur, and the king mounts.

The pagans flee. It is not the will of God that they should remain. Now the French have achieved the triumph which they had hoped for.

From The Song of Roland. Considered one of the exemplary “chansons de gestes” or “songs of deeds,” the French epic poem dating from around 1100 glorifies the Battle of Roncesvalles, a historically negligable skirmish between Charlemagne and Basque forces.

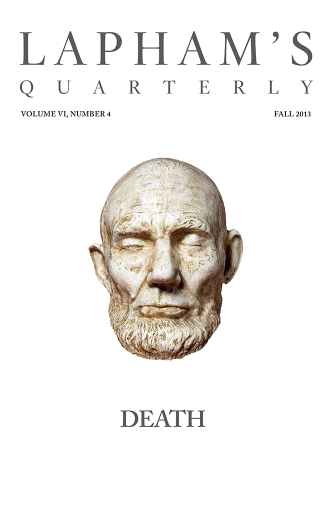

Back to Issue