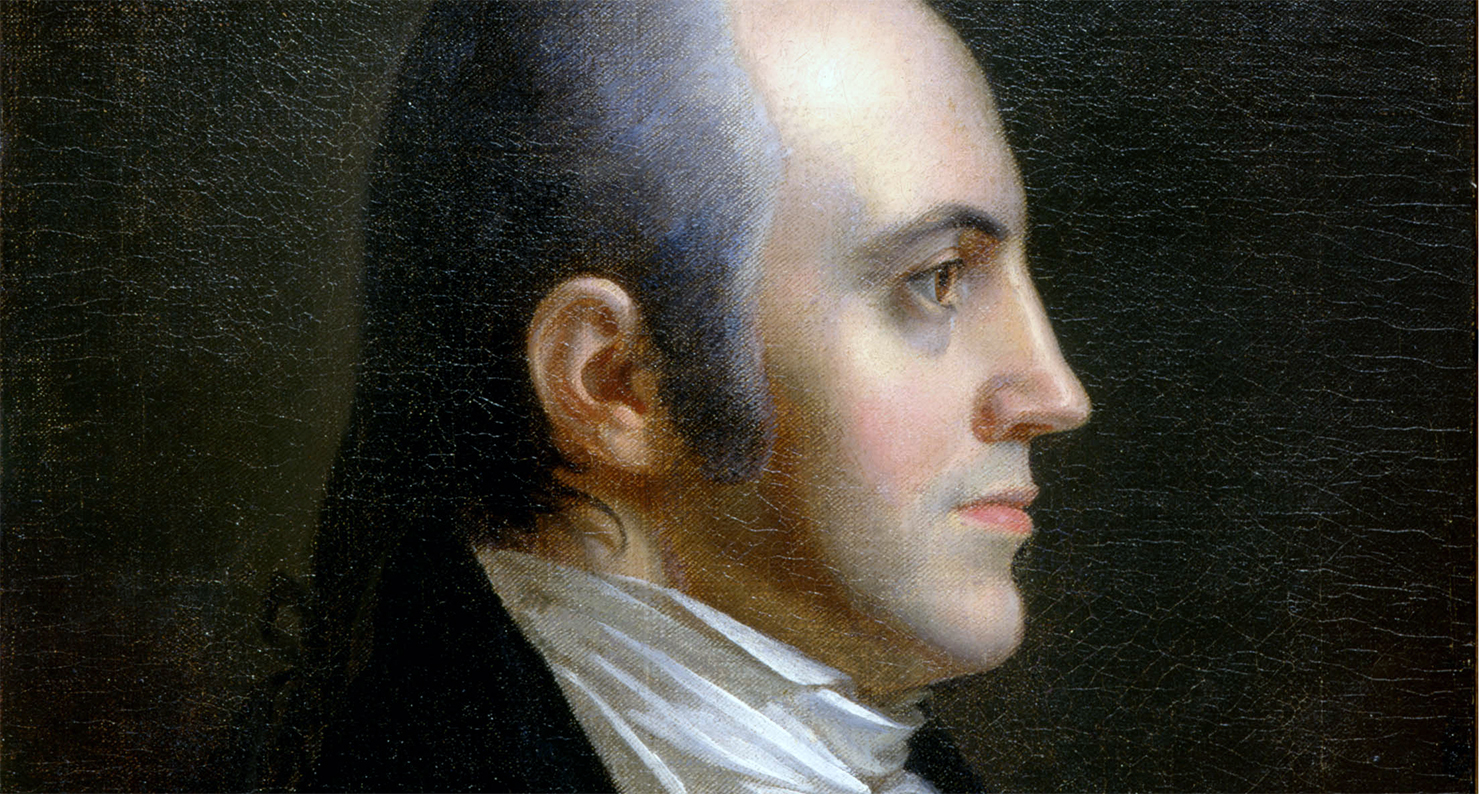

Portrait of Aaron Burr, by John Vanderlyn, 1802.

On the anniversary of the Hamilton-Burr duel, which took place on July 11, 1804, Lapham’s Quarterly contributor Paul Collins—who is finishing a book on the earlier, friendlier times of Hamilton and Burr—pointed us to an odd coda in the life of Aaron Burr, once, and perhaps still one of history’s most infamous men.

By the time of his death in 1836, Aaron Burr had largely faded from the national consciousness, remembered for his arrest for treason in 1807 and, of course, his part in the duel that killed Alexander Hamilton. The third vice-president of the United States under Jefferson, married twice and surviving his only legitimate child, Burr was described in an 1881 Washington Post retrospective as a bitter, lonely old man who cared not for his reputation as boogeyman to neighborhood children:

Bereft of friends and home, left childless by the awful fate of his only daughter, Theodosia, the last years of his life were sad beyond expression. He dragged out the days beyond four-score in proud loneliness, asking no sympathy and despising the word that had forgotten him…the children used to scamper away in mortal terror when the master of the mansion passed through the grounds.

Burr was consistently characterized as cold and imperious, but allegations that he’d practiced his marksmanship skills in advance of the duel—preparation for a duel would have been considered ungentlemanly—have mostly been considered unfounded, with some noting Hamilton and Burr’s equal war experience as both served in militias during the Revolution, and others pointing out that Burr had taken part in another duel, one where his shot missed its intended target by a wide berth.

Curious, then, is this aside from Oliver Mourhose, who arrived in New York in 1803 and detailed his life there in the post-colonial city in “A Boy’s Reminiscences,” published in the journal Old New York:

While Burr was in France his house on Richmond Hill was untenanted and closed, but a tool house on the place was found to be open by us rambling boys, and there at one end we found still remaining the target upon which he doubtless practiced with his pistol before the duel. He could make the distance about thirty feet, and for that distance the practice was excellent.