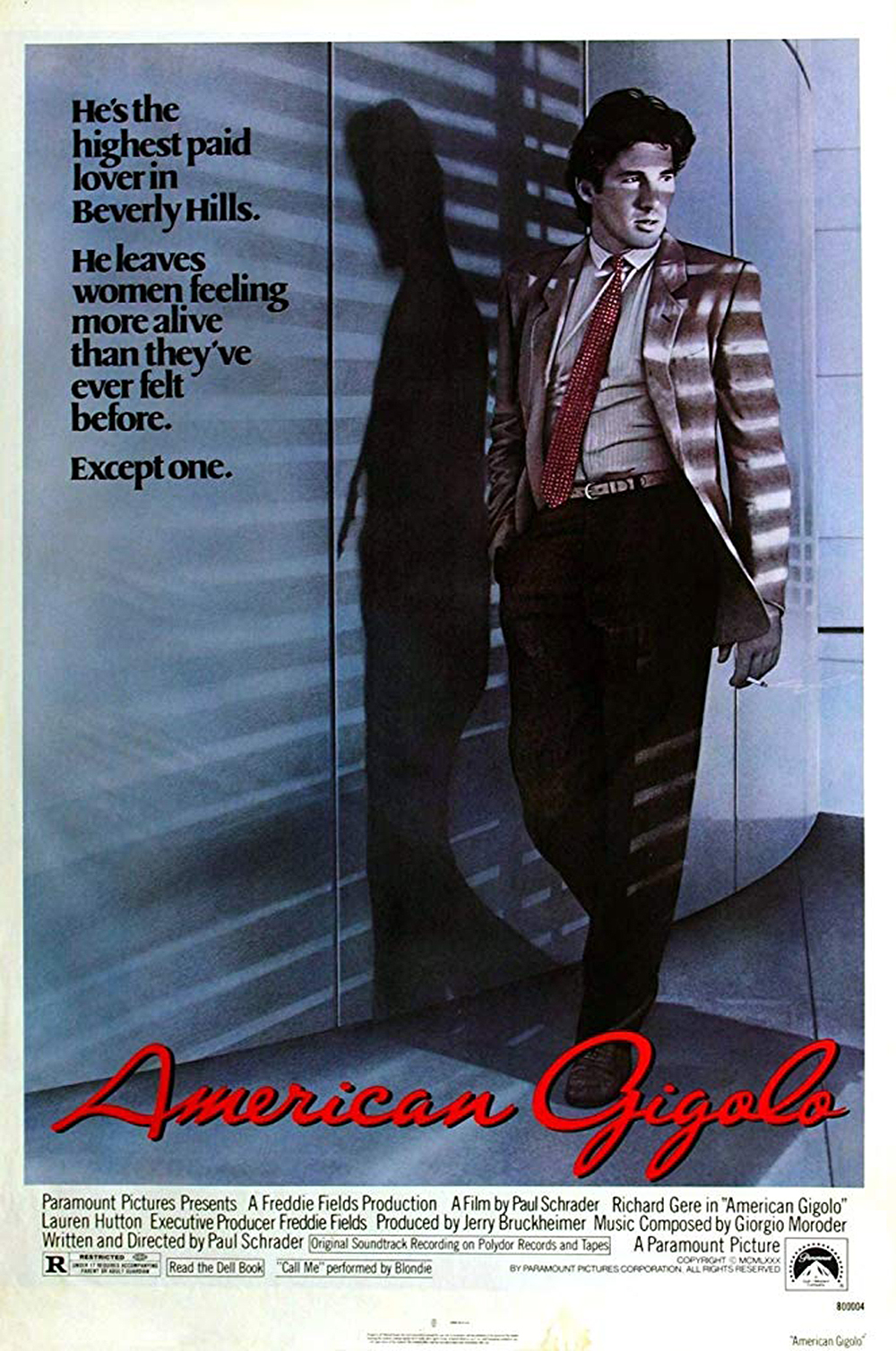

Poster for American Gigolo, 1980. Paramount Pictures.

When he was twenty-five years old, the fashion designer Giorgio Armani made a rule for himself that was not like something out of a high-concept 1980s film but rather precisely the plot of one: no dancing. This had nothing to do with a Footloose-esque sense of morality. In the same way he has been known to cut up photographs of himself that he doesn’t like, Armani cannot bear to think he might look stupid. Throughout his career as one of the most reputable and well-regarded fashion designers in the world, he has been known for this punishing severity toward both himself and his staff—in a Vanity Fair profile published in 2000, Judy Bachrach concluded that he could be called an “Italian Puritan,” austere and uncompromising, living only for his work. “His love affairs,” she summarized, “are of long duration (former flames transmuted, after passion subsides, into a perpetual part of the tribe) and always with colleagues. He doesn’t smoke, rarely drinks, and accuses those who indulge of being ‘wild.’ His evenings are a bowl of pasta, bed at eleven, quiet.”

Armani’s work as a fashion designer has moved beyond setting trends and selling suits. In providing costumes for film and television, his rigid sensibilities defined the aesthetics of an entire decade—most crucially right as it began, with the wardrobe for the 1980 Paul Schrader film American Gigolo, the story of Julian Kaye (Richard Gere), a sex worker with similarly high standards for himself and his clients. Gigolo was a critical hit and, although something of a commercial failure, established Gere’s status as a movie star and Armani’s collections as the fashion standard for the era’s ethics and tastes, a moral code best seen in aesthetic principles. In the thirty-eight years since the film was released, it has become almost a cliché; periodically a men’s magazine or a fashion magazine will declare that the look is all over the runways again, or that it’s a model for the way men should dress. The wardrobe of the film is both a remarkably accurate artifact of its time and a modern, contemporary interpretation of a man who dresses well and knows it.

Gigolo is a neo-noir, a crime conspiracy set in the shadows of a sunny place and under the trench coats of its unlikely heroes. Julian is a smug but somehow lovable man who works independently, under many coded guises. Most often calling himself an “interpreter” or “guide,” he speaks multiple languages and owns a driver’s uniform to go with his chauffeur’s license, so that he can hide his real source of income. He holds himself apart from other sex workers, male and female, taking jobs from different contacts but refusing to work for anyone exclusively, and constantly repeats his rules—he’s not a woman, he reminds everyone, meaning he doesn’t have to compromise. He isn’t gay and won’t work for men. He doesn’t like working for couples but makes exceptions if the man only watches, and he refuses to do violent kink or “rough tricks.” More than that, Julian is special, which he’ll be the first to tell you. When we meet him he’s learning Swedish for a very important client arriving in a few days. It appears that that’s as far into the future his mind can see. He makes no other references to other plans, mentions no other goals or dreams. Small bits of information come to us about his background; at one point he mentions he used to be a pool boy at a fancy hotel. When he visits a gay bar late in the film looking for help, patrons greet him in a way that makes it clear he used to be a regular.

At a hotel bar where everyone knows his name if not his profession, he sees Michelle (Lauren Hutton) speaking fluent French to a waiter and misidentifies her as a potential client. She correctly guesses what he really does when he tells her he’s a translator who speaks many languages—“Plus the international language,” Michelle says, which is a funny way of putting it—and for some reason they’re drawn to one another. She’s the wife of a powerful senator, so you know it’s going to get messy—and it does. Julian goes on a last-minute job as a favor to his friend Leon, but he’s upset to find that the couple is the kind of rough trick he usually rejects. That’s not what Julian wants to think of himself as providing; he provides pleasure, he tells us again and again, though we almost never see him at work in bed. The wife of the couple is found murdered days later, and Julian becomes the primary suspect. Already vulnerable as the lover of a powerful politician’s wife, he’s exposed and all eyes are on him—maybe. Is he being framed? Is he being watched? Is he being followed? Who can he trust?

The previous decade of cinema had seen new paranoiac heights, with films such as The Conversation, Klute, and The Parallax View placing their characters under sinister scrutiny, the amplified static tones of white noise under every phone call and the camera’s eye over every head. Gigolo predicted a paranoia we now take for granted: the feeling that hides underneath self-surveillance and other kinds of vanity in a constantly surveilled world, obsessing over your looks because what if someone sees you? What if someone is watching you right now? Keeping up appearances is a form of control for those who feel watched with every move they make.

Armani grew up in northern Italy during World War II. He was badly burned in an accident—some neighborhood kids had taken gunpowder from an Allied cartridge and lit it on fire—and was hospitalized for over a month. He still has a scar on his foot and problems with his vision. His sister Rosanna remembers that for a long time, whenever a plane flew overhead, he would throw himself into a ditch. The end of the war brought no peace to the Armani family: his father was imprisoned for his fascist sympathies, and when Armani was still recovering from his injuries the other children would steal his crutches. In 2006 Armani told T Magazine that he used to avoid watching Italian neorealist films depicting that era; he had lived through it already. He did eventually learn to love them, though—it’s the basis of his ongoing friendship with Martin Scorsese.

After his father was released, the family moved to a modest neighborhood in Milan. Armani would walk down the Via Montenapoleone, the street with all the best shops, and watch the women who were there to do more than just look. He briefly considered photography and even medicine, but after getting a job as a window dresser for a department store he decided to go into fashion and ultimately went to work for Nino Cerruti, a menswear designer renowned for his use of wool in suits. Armani, looking at bodies and wanting his hands on textures, saw that men and women both wanted something new and easy to wear. In a 2004 profile for The Guardian, Suzie Mackenzie describes how a childhood under fascism, and then seeing his father in prison, influenced his aesthetic and his ethics: “A reaction against hierarchy, a distrust of conformity and rigidity in all its incarnations. As a child he had seen firsthand the perils of a uniform—he must have understood the psychological comfort and equally the danger in such conformity.” He took the padding out of jackets and tried different, lighter fabrics. One myth claims that he and Sergio Galeotti, his boyfriend at the time, sold their Volkswagen Bug to start their business.

Armani’s first collection of suits was a revelation for the new kind of round-the-clock professional: men and women who donated their bodies to capitalism. Not quite suit and not quite sport, his clothes felt good to wear and you looked good wearing them. Gianni Versace, who was constantly set up as a competitor and rival to Armani, made suits that were expressly of his time, though the oversize silhouettes drew obvious parallels to the zoot suits of the 1940s, and the light materials were meant to evoke the Neapolitan tailors Armani watched as a child, men who always worked with the summer heat in mind. There were no shoulder pads in the jackets or creases in the pants, and the materials—wool, cashmere—felt luxurious. The oversize cuts were paradoxically alluring: bodies are inherently flattered by clothes that make the assumption of hiding something good. In the late 1970s and through the early 1980s, male vanity was still considered either an oxymoron or a shameful principle. Easily satirized and frequently derided, the implicitly feminine qualities of intensive grooming were made more necessary and therefore more macho so that menswear could make higher profits. Armani allowed men to feel graceful in a way that still retained a traditional sense of masculinity, a languid sexuality that referenced power without announcing it—soft dominance for the gentle patriarch.

The media—and to some extent the entire fashion industry—encouraged the idea that Armani existed either in opposition to or competition with the other Italian designers of the time. Miuccia Prada, who was already gaining recognition for her cerebral and eccentric looks, was expanding into the ready-to-wear business that would make her one of the most powerful designers still working today. In her posthumous biography of Gianni Versace, Deborah Ball writes extensively of the differences between Versace and Armani and how much those differences played into media coverage of both. Versace was the absolute opposite of Armani in every way—bright and tight dresses, loud and colorful fabrics—and a popular line of the time was that Armani dressed the wife, while Versace dressed the mistress. This says more about the false dichotomy present in women’s retail (and women’s lives) than it does about the women themselves—after all, in this joke, the same man is assumed to be paying for both outfits. Still, women were expected to choose a side and show their loyalties on their bodies.

These Italian designers did have one thing in common: they wanted to upend the idea that Paris was the center of all fashion. People were beginning to feel that, with the exception of Yves Saint Laurent, French couture was far too restrictive and old-fashioned for the 1970s and 1980s; it was too bougie, and not in the fun way. There are many reasons Milan became a strong contender for the fashion industry’s attentions around this time, but the immense success of brands such as Armani, Prada, and Versace is at the crux. Armani also was one of the first designers to see how profitable it could be to dress celebrities on red carpets; his designs may have been in opposition to his peers, but he was very much working in tandem with Hollywood.

Studio costume designers used to dress celebrities for red carpets, but by the 1970s costume departments had shrunk and actresses had to dress themselves. It turns out that actresses are pretty bad at that. Stylists were invented more out of necessity than vanity, and direct relationships to couture and ready-to-wear designers became a crucial currency for those who made dresses and the women they wanted to wear them. Former society columnist turned Armani publicist Wanda McDaniel claimed that Armani became the first fashion house to open a West Coast office when it opened a 13,000-square-foot boutique in Beverly Hills. The proximity to fame became as good as fame itself. Armani fashioned itself as not just the clothier of choice for celebrities but as their savior. Sean Connery once lost his luggage while on his way to Italy, and the Rome store stayed open late to outfit him in a whole new wardrobe. Jodie Foster has recalled that her pre-Armani red carpet days almost always end up on some worst-dressed slideshow.

Armani understood that movies are advertisements, in their own way—they sell a vision of life, which is almost always better than a vision of reality—and that movie stars are always representatives of that fantasy, whether they’re on the screen or off the clock. John Travolta was already a fan of Armani when he was cast in Gigolo, and he chose forty Armani outfits to wear throughout the film. Though he was replaced by Gere, he became a loyal Armani client to this day, and the wardrobe remained in the film.

Understanding the impact of Gigolo on Armani’s public perception is complicated, so for simplicity’s sake let’s look at the numbers. In 1975, its first year of business, Giorgio Armani S.p.A. did $14,000 in sales; the following year it brought in $90,000. By 1981, the year after Gigolo was released in theaters, company sales were $135 million. Even taking into account the standard rate of growth for a successful line of clothing, this is an unprecedented commercial expansion. A rumor persisting to this day is that, because of Gigolo’s impact on Armani’s sales, Gere never has to pay for a single item of Armani clothing. He can walk into any Armani store, anywhere, and walk out with whatever he wants. Is this true? That’s not really the point of the story.

For the 2000 Vanity Fair article, Gere remembered trying on the all-Armani wardrobe, saying it was “quite stylized, big shoulders and thin waists, thin lapels,” with a single point of reference for the neutral palette: “It was like looking at an old carpet where the natural colors blend and even bleed, as opposed to some of those new carpets made of plastic fibers where the colors are monolithic.” Such depth given to the ordinary is a metaphor for all of Armani’s collections, and the designer’s presence is felt in everything Gere’s character does. One iconic scene shows Julian finishing a line of coke and trying to pick out an outfit for a job, flipping through blazers hanging in the closet and pulling out drawers full of coordinating ties and shirts. When Alice Rawsthorn wrote about the scene for T Magazine, she pointed out that “Gere was perfectly cast for the narcissism of the moment—after disco but before AIDS, when gym culture was taking off and even straight men were losing their hang-ups about being seen to look good…It was a priceless advertisement.”

The third act of the film follows Julian as he tries to clear his name and his reputation, predictably abandoned by the rich and powerful women he took so much pleasure in satisfying. He rips up his apartment and his car looking for proof that he’s been framed. He even enters a hotel restaurant without putting on a dinner jacket, a sign that he’s really in a crisis. Paul Schrader told GQ that he always thought Gere was more interested in the character than the clothes, which missed the point: “To me the clothes and the character were the same. I mean, this is a guy who does a line of coke in order to get dressed!” Julian’s character may not keep a diary like the protagonist of Robert Bresson’s Pickpocket, Schrader’s inspiration for Gigolo, but he keeps a wardrobe. His entire conception of who he is and what he does is tied to how he looks. Another famous scene shows Gere completely naked—his full-frontal nudity is frequently mentioned in writing about the movie—but the monologue he delivers at that moment is far more revealing: he prefers to work for older women, he tells Michelle, because when they orgasm, it really means something. He talks about a client who hadn’t come in ten years. It took him three hours, he explains, and he wasn’t even sure he could do it. But, he asked, “Who else would have taken that time? Cared enough to do it right?”

Julian’s sexuality is strangely muted, barely present in the film despite his profession—something Hutton noted when considering why Gigolo was a critical success, what she called a “stylish hit,” but not financially successful. For a long time she thought it was a failure. “I think it wasn’t a hit because you never get to see why he’s such a good gigolo. You never see how he makes love to a woman,” she said. It’s true—nudity is not analogous with sensuality, and Gigolo is a cold film about warm bodies. Hutton’s wardrobe was made by Basile, another Italian brand with a slightly lower profile but a sensibility similar to Armani’s: excellent fabrics with structural references to the 1940s—high-quality cashmeres, silks, and denim—worn in a palette complementary with Julian’s. Michelle favors masculine silhouettes, particularly in her trench coats (Hutton says she frequently borrowed the wardrobe assigned to Gere when they were filming) and button-down shirts, though they’re worn in a way that only underscores her femininity. Under Schrader’s direction, the only sex scene is more about what the body comes into contact with than the body itself—Hutton’s silk blouses are exchanged for high-thread-count sheets, a love affair with fabric all a part of Julian’s work.

Richard Martin, a former curator of the Costume Institute of the Metropolitan Museum (who also reportedly wore only Armani), once called Armani a “design conservative” and observed a strange dissonance in the designer’s clientele: they believe in fairness, a sense of what’s earned and what’s right, and that their choices are above reproach. In Martin’s reading, he sees that “the same attitude that leads people to say they are not going to spend money on clothes leads them to pay $3,000 for what they think of as a classic investment piece from Armani.” This is the common exceptionalism that Julian displays so perfectly: he’s special, he thinks, not considering that everyone else thinks the same, or that what makes him special amounts to a collection of elegant, beautiful, and mass-produced accessories available for purchase to anyone who can afford the inflated markup. By the end of the film, he has traded the contents of his closet for a prison uniform, humbled but a better man for it. Exactly a decade later, Gere would play a character on the other side of a similar transaction, as john to Julia Roberts’ sex worker in Pretty Woman. The ethics of sex work in that film are different from Gigolo, but the most telling sign that a decade has elapsed are Gere’s suits in the film, immaculately tailored by Nino Cerruti, hinting at the sharp silhouettes of the 1990s. Yet in real life Armani’s primacy was only growing: Roberts wore an Armani suit to the 1990 Golden Globes. The ending of Gigolo shows Julian in jail, pure in his innocence and anonymous in his uniform—as if the romantic reconciliation between Julian and Michelle was deserved only after he has been stripped of his material vanity, his Armani wardrobe just a record of someone he used to be.