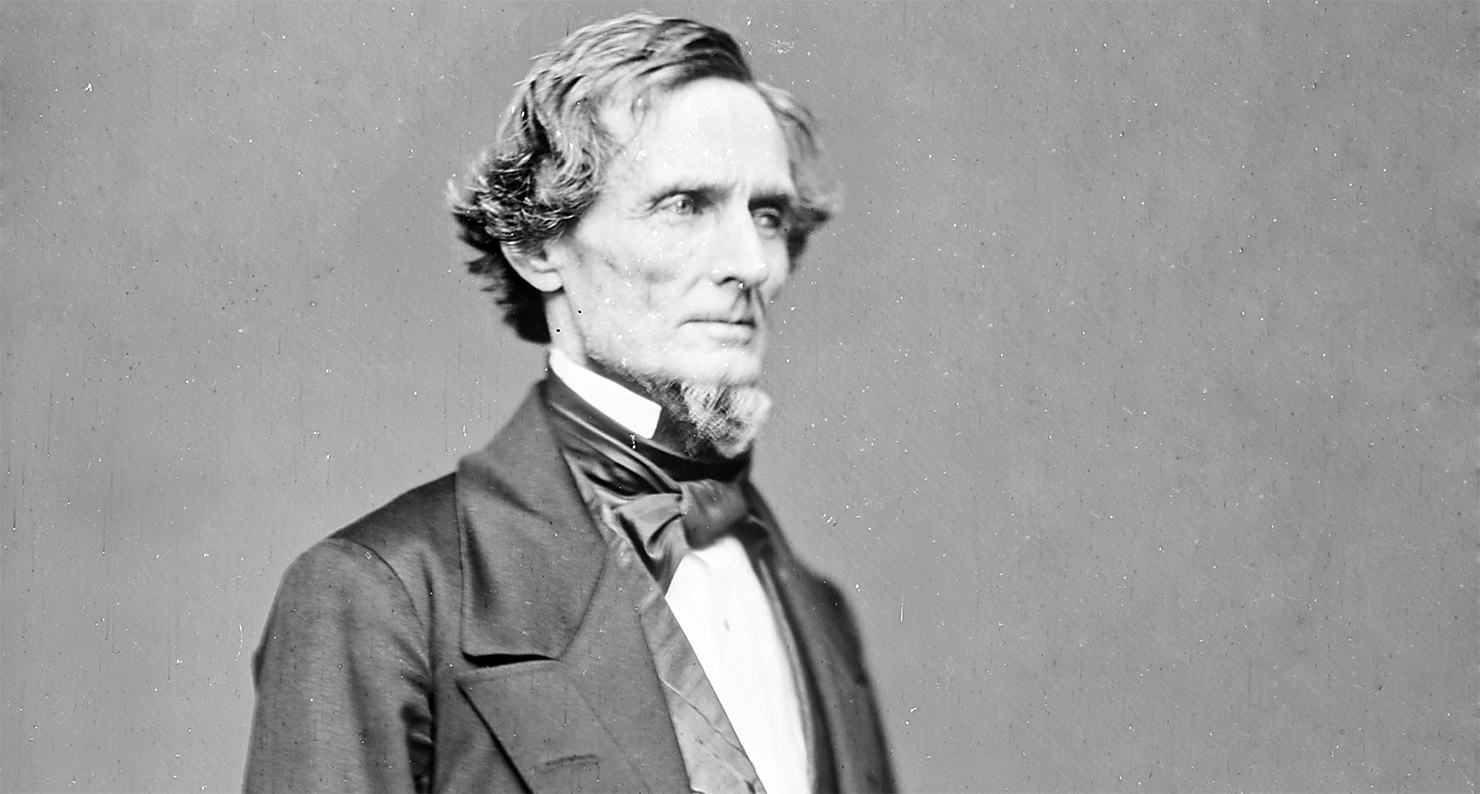

Jefferson Davis, 1861. Photograph by Mathew Brady. National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, DC.

From 1817 to 1833, West Point was ruled by the iron fist of Colonel Sylvanus Thayer, who as superintendent had revolutionized discipline at the elite military academy, prohibiting cadets from leaving the grounds without permission, cooking in the dorms, or dueling. A diet of beef, bread, and water prepared his young students for military rations. Until 1825, the cadets were allowed to drink on two holy days: the fourth of July and Christmas. That year, however, the fourth of July celebration had devolved to a state not fitting a West Point cadet, when a “snake dance” led to the hoisting of the school’s Commandant on the students’ shoulders. Thayer was irate and the party was over. From 1826 onward, no alcohol was allowed on campus on pain of arrest and expulsion.

The were two taverns located just outside the walls of West Point: North Tavern and Benny Haven. The latter allowed the bartering of shoes and blankets for liquor, but not uniforms—nothing from the school itself. (Edgar Allan Poe would spend a majority of his time at West Point at Benny Haven, and his continued absences eventually led to his dismissal after one year.) The taverns were technically illegal to visit, but as long as a cadet wasn’t caught, or a commanding officer turned a blind eye, they remained an essential place to cool off with friends, enjoy a warm flapjack, and most importantly, drink up.

One member of the class of 1828, Jefferson Davis, the future president of the Confederacy, had a history of being arrested or censured for leaving his post to drink at the taverns: he was the first student to be arrested for going to Benny Haven. Another time he drunkenly fell sixty feet down a ravine, his friends shouted after him to respond if he wasn’t dead. When a group of Davis’ friends suggested they flout the superintendent’s new law and throw a Christmas Eve rager the night of December 24, 1826, Davis was on board. Their choice of holiday beverage: the notorious eggnog.

Although eggnog in one sense or another may date back to fourteenth-century England, the eggnog that the cadets planned to enjoy that evening was a distinctly American tradition. Nog is essentially a mixture of four items found on any colonial farm: the product of chickens, cows, sugar, and booze, the type and taste of which could be masked with spices. George Washington’s particular nog recipe included rye whiskey, rum, and sherry, but the kind of liquor required was never set in stone. The only rule: the more the merrier.

And so it was for the West Point cadets. In the days leading up to Christmas Eve, four sets of students blew off their posts to secure alcohol for the occasion. One rowed across the river to the North Tavern, another group bought a gallon of brandy and a gallon of wine, one organized a gallon of liquor on credit, and another bought the eggs, milk, and nutmeg for the nog. Mutton was smuggled in from Benny Haven, should anyone need a nibble.

The party started around midnight, with about nine cadets in one dorm room, and gradually increased in size and migrated to another room. Things started to get loud around 2 a.m., when Davis and eight others were heard singing and another student tried to quiet them down. By 4 a.m., the commotion could be heard through the floorboards, and faculty member Captain Ethan Allen Hitchcock went to investigate.

Davis, in a classic frat boy move, hurried into the room to warn the thirteen friends inside—“Put away the grog boys, Old Hitch is coming!”—only to realize Old Hitch was already there. Davis and others were placed under arrest and ordered to their rooms. Hitchcock read the group the Riot Act, which declared any group of twelve or more unlawfully assembled, and satisfied, left the room fifteen minutes later.

What happened next resulted in the largest mass expulsion in West Point history. (The night was given the minute-by-minute treatment by James B. Agnew in his 1979 book The Eggnog Riot: The Christmas Mutiny at West Point.) Angry at Hitchcock for ruining their party, the cadets decided to hunt the captian down and harass him. Over the next two hours, a cat-and-mouse game between the students, the faculty, and sober students who woke up to take arms against their drunken brothers, led to broken windows and furniture, unsheathed swords, hijacked drum and fifes, a lieutenant who was knocked out cold, and one discharged pistol. The 6 a.m. reveille was a confusing chatter of horns, drums, yelling and cursing. Twenty minutes later, most of the cadets stumbled down to roll call, some still too drunk to be hungover.

Jefferson Davis had missed everything. (His prized future general Robert E. Lee also attended West Point at this time, but he declined to take part in the party.) Instead of following his friends and resisting arrest, Davis stumbled to his room, retched a little, and passed out cold. In his memoirs, Davis would claim that he didn’t name names, but in fact the records show that he implicated his roommate in the melee when the cadet returned to their dorm, waking Davis up as he loaded his gun (this was single unloaded pistol of the evening)

Twenty-three cadets were arrested, nineteen were expelled, and Davis was spared, graduating at the bottom third of his class. His time at the academy brewed a long-lasting hatred for Yankees. His love for eggnog remained true.