c. 220: Woodblock printing

The earliest type of printing involved carving a relief pattern into blocks of wood, which would then be inked and pressed onto cloth, and later paper. A woodblock could be reinked and stamped many times, saving labor compared to scribal work, despite the initial investment of labor in carving the block. The earliest extant examples are from China; the technology spread from there to Japan and other parts of the world. Color woodblock printing began in China in the fourteenth century, initially with only the addition of a single color, usually red. A technique for five-color printing called nishiki-e became widespread in Japan in the 1760s.

1040: Movable type

The first movable type—printing technology that uses small blocks of type for individual characters that can be rearranged as needed—was invented by Bi Sheng in China. Movable type came to Europe around 1450, when Johannes Gutenberg began using it with his printing press. The first items Gutenberg printed were a German poem, some religious tracts, and a popular German grammar book, but he is most famous for producing the first printed edition of the Bible, of which forty-nine copies survive today.

c. 1500: Pocket-size books

Printing books pocket-size is one way that printers and publishers have been able to offer less expensive options for buyers. The Italian publisher Aldus Manutius was known for his small-format books—quarto sized, made of paper folded into four, and octavo sized, made of paper folded into eight. In 2009 the Dutch publishing company Jongbloed BV invented the dwarsligger, a small book printed on very thin paper that is intended to be read one-handed. The text is printed parallel to the binding, so the reader can flip the pages up with a thumb—like scrolling on a smartphone. The smallest book ever produced, Teeny Ted from Turnip Town, is carved into crystalline silicon and is only a hundred micrometers tall. In this case smaller does not mean cheaper: the list price is $15,000.

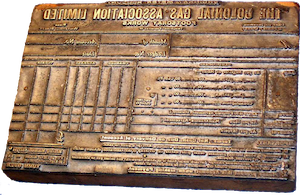

c.1700: Stereotyping

One of the greatest costs in the production of movable-type books was the actual setting of type, with each letter placed individually by hand in the printing block. But the invention of stereotyping—where a mold is made of a typeset page and a whole page is then cast in a plate of type metal—made reprinting a book much less expensive. Early forays into creating stereotypes (also called clichés) almost always involved Bibles, a book printers knew they would print again. Printers later created stereotypes for books they expected would go into second (or more) editions. Since producing stereotypes nearly doubled the cost of composition, publishers were taking a gamble on what books the public wanted to buy.

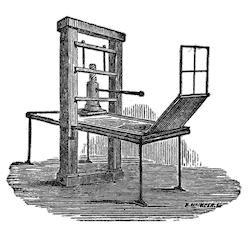

1814: Steam press

The first move toward truly industrialized printing was the application of the steam engine to the press. The first newspaper to adopt the steam press was the Times of London. On November 28, 1814, editor John Walter II surprised the printers waiting to produce that day’s edition with a finished copy of the paper, printed the night before on the new steam press. In the 1820s wider adoption of the steam press lowered the cost of book production, making it possible to produce books more quickly and more cheaply.

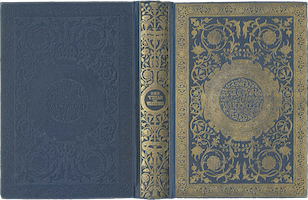

c. 1830: Clothbound books

Before the nineteenth century books were usually sold in temporary bindings—paper wrappers or paper-covered boards—that buyers could then take to a bindery to be re-bound in leather. As the book business expanded, publishers wanted to be able to sell durable, permanently bound books directly to consumers at a price lower than the cost of a leather binding. Cloth bindings, in combination with a new technique called case construction that created a binding separately from the printed pages, made that possible.

c. 1845: Paperback books

Like clothbound books, nineteenth-century paperbacks were intended to increase book sales by offering a cheaper option. In Britain they were called yellowbacks for their bright covers and were usually stereotyped reprints of novels. Beginning in 1848, Routledge published over a thousand yellowback titles over five decades in its Railway Library. Penguin began publishing its signature color-coded paperback reprints in 1935.

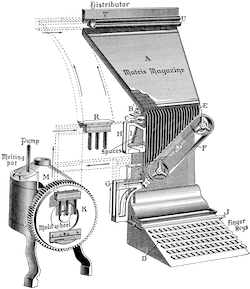

c. 1884: Hot-metal typesetting

Instead of setting premade type in a printer’s block, hot-metal typesetting casts the type into the needed letter and sets it automatically, controlled by either a keyboard or paper tape. In one common variety, Linotype, each line of type was cast as a continuous block. By reducing the labor needed to set type, hot-metal typesetting made printing cheaper and faster and was quickly adopted by newspapers and magazines. Books were much more likely to be printed by monotype, where each letter or glyph is cast separately, because it allowed for manual corrections.

Lapham’s Quarterly is running a series on the history of best sellers, exploring the circumstances that might inspire thousands to gravitate toward the same book and revisiting well-loved works from the past that, due to a variety of circumstances, vanished from the conversation after they peaked on the charts. We are also publishing a digital edition of one of these forgotten best sellers, Mary Augusta Ward’s 1903 novel Lady Rose’s Daughter, with a new introduction, annotations, and an appendix. To read more about the project and explore the other entries in the series, click here.