Adam and Little Eve, by Paul Klee, 1921. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, The Berggruen Klee Collection, 1987.

By marriage, the husband and wife are one person in law: that is, the very being or legal existence of the woman is suspended during the marriage, or at least it is incorporated and consolidated into that of the husband: under whose wing, protection, and cover, she performs everything; and...her condition during marriage is called coverture.

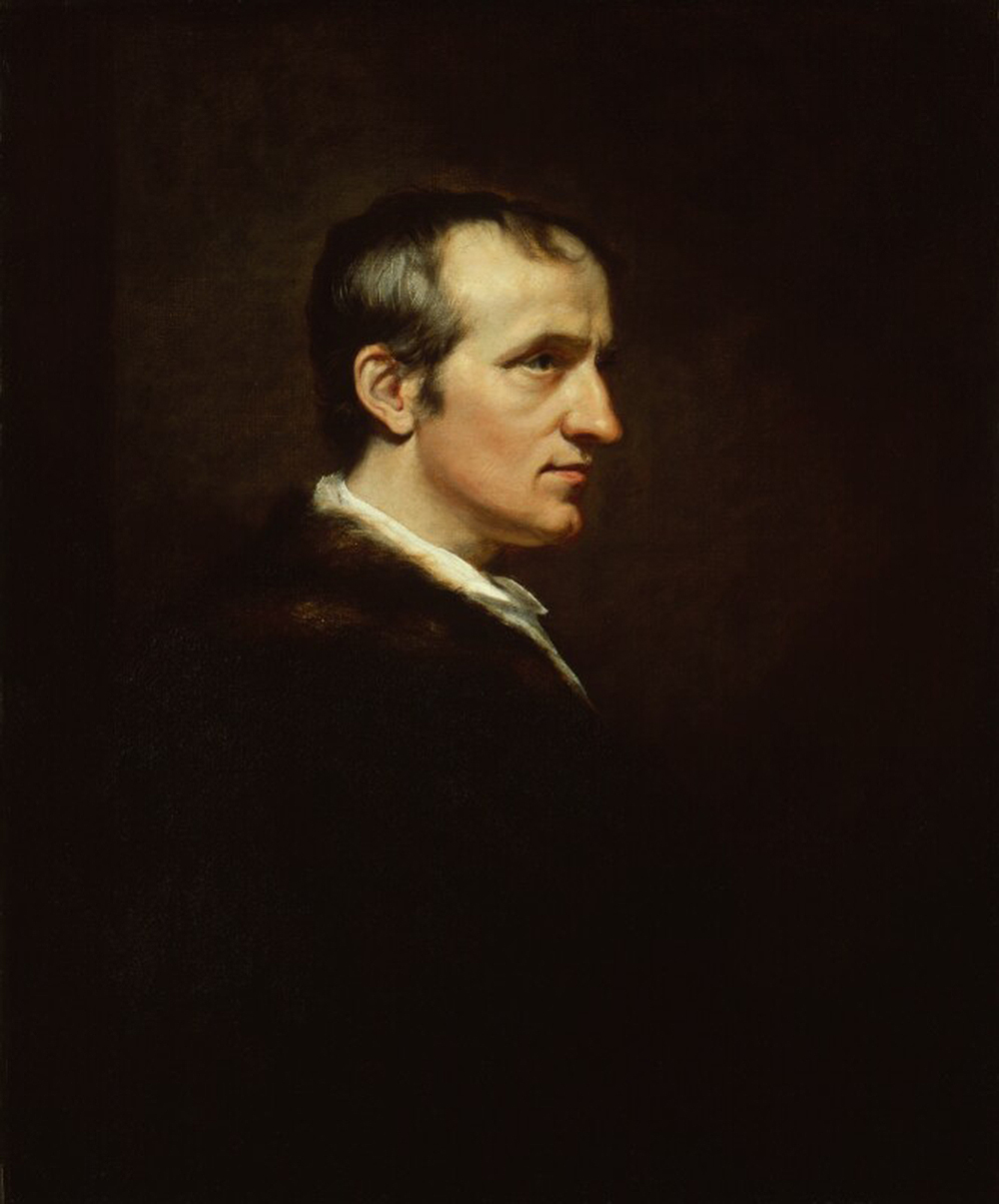

—William Blackstone, Commentaries on the Laws of England (1765), adopted in American common law

Thy desire shall be to thy husband, and he shall rule over thee.

—Genesis, 3:16

“The laws respecting women…make an absurd unit of a man and his wife; and then, by the easy transition of only considering him as responsible, she is reduced to a mere cipher,” Mary Wollstonecraft wrote regarding coverture in A Vindication of the Rights of Woman in 1792. Coverture was an inverse of the biblical creation story, in which a lonely Adam was given a helpmate who had been fashioned from his rib. Under the laws of coverture, a married woman was subsumed within the body of her husband and ceased to exist legally. She could not own private property, earn wages, sue or be sued, or execute a will without her husband’s consent. She could not vote, serve on a jury, or divorce (except in cases of adultery). In the rare case where a divorce was granted, she could not maintain custody of her children. In the event of her husband’s death, she could not be the guardian of her minor children and her husband’s property typically passed to the eldest male heir, who would hopefully be inclined to look after her.

The revolutions in both America and France challenged the concept of coverture. As men and women questioned the fairness of a monarch’s dominion over his people, so too did they question the right of a husband to rule over his wife. Social reform tends to progress in a lopsided manner, so while more women and men agitated for equality, the laws maintained the status quo. The laws regarding marriage were at best archaic and at worst villainous. Husbands held exclusive power over their wives, and women’s position in marriage was similar to slavery. Early feminists identified marriage as the institution that bound women in subservience to men; it is no coincidence that the movements for female emancipation and the abolition of slavery were initiated out of the same discontent. Even though they rejected the laws of marriage, social reformers of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries—the majority of whom were white, highly intellectual, and politically radical—could not help themselves from falling in love and wanting to express that love through marriage. These rebel couples struggled to fit their ideals into such an unsuitable frame and often had to write their own rules—or at least build on ideas from fellow reformers.

Mary Wollstonecraft and William Godwin | Anniversary: March 29, 1797

Wollstonecraft’s most famous work, A Vindication of the Rights of Woman, is to women’s rights what John Locke’s Second Treatise of Government (1690) and Montesquieu’s Spirit of the Laws (1748) are to the Declaration of Independence and Federalist papers. Without her, nineteenth-century suffragists would have lacked a framework upon which to build. Wollstonecraft’s own thinking about the treatment of women in society began in childhood as she witnessed her alcoholic father’s physical abuse of her mother. She blamed the unfair treatment of the sexes for giving her father—and men, generally—the power to be tyrannical, and she likewise faulted the patriarchy for her mother’s timidity, which she saw as an indoctrinated rather than inherent quality. Ever brave, she often placed herself as a physical barrier between her mother and her father. She became determined to help women escape unequal marriages; when she was twenty-four, she hid her sister, fleeing an abusive relationship, until a separation could be secured.

Wollstonecraft’s primary cause was female emancipation. She believed the lack of education for women and the institution of marriage perpetuated a system of dependence and inferiority. Women were not provided the same opportunities for either mental or physical growth and hence, she wrote, grew up to become intellectually foolish and physically weak creatures rather than living up to their full capacity as rational beings. Men were trained for their future, but women were schooled only for marriage. As she wrote in A Vindication,

the obedience required of women in the marriage state comes under this description; the mind, naturally weakened by depending on authority, never exerts its own powers. [Women’s] strength of body and mind are sacrificed to libertine notions of beauty, to the desire of establishing themselves—the only way women can rise in the world—by marriage.

She did not despise marriage as an institution but argued that men and women should be educated in the same manner and presented with the same opportunities, so marriage could be a meeting of equals rather than a man and his subordinate wife.

Her life was an experiment in living independently. In her twenties, she rejected working as a governess to pay off her father’s debts and instead worked as a translator for the radical London publisher Joseph Johnson. During this time, she became involved with Henry Fuseli—painter of The Nightmare—and in the white-hot passion of their affair, she approached his wife proposing all three of them live together. His wife declined, and Wollstonecraft was rejected from the Fuseli circle of intellectuals shortly thereafter. She moved to Paris to support the French Revolution, and while there she fell in love with American merchant Gilbert Imlay and had his daughter. They never married. She and her infant daughter Fanny returned to London, where once again under the tutelage of Joseph Johnson, she became acquainted with William Blake, Thomas Paine, William Wordsworth, and William Godwin.

The third time was the charm, and Wollstonecraft and Godwin became the modern era’s first rebel power couple. When they met, Godwin was already established as a godfather of anarchy, communism, and atheism. He was also an ardent opponent of marriage and most other social institutions. “The abolition of the present system of marriage appears to involve no evils,” he wrote in 1793. He viewed the very custom itself as absurd, stating that marriage “is for a thoughtless and romantic youth of each sex, to come together, to see each other, for a few times, and under circumstances full of delusion, and then to vow to eternal attachment.” Godwin also recognized the implicit unfairness to women:

Add to this, that marriage, as now understood, is a monopoly, and the worst of monopolies…so long as I seek, by despotic and artificial means, to maintain my possession of a woman, I am guilty of the most odious selfishness.

He believed marriage should not involve the law or a binding agreement, but should rather be a meeting of two friends who freely agree to share their lives and who likewise are at liberty to leave. Despite his contempt for clichéd romance, even grumpy Godwin was not immune to the charms of Mary Wollstonecraft, gushing, “Wherever Mary appeared, admiration attended upon her.” He called his relationship with her “friendship melting into love…I had never loved till now.”

Already living together, the two married when Wollstonecraft was five months pregnant, to spare her the humiliation of being an unwed mother for the second time. (Social rules were, then as now, a tangible burden.) She gave birth to their daughter—who would grow up to become Mary Shelley, author of Frankenstein—but died eleven days later from puerperal fever, leaving Godwin devastated and the sole parent of both Mary and Fanny. (He eventually remarried and reared five children, all from different sets of parents.) Scandal plagued Wollstonecraft even after death. Her posthumous novel Maria boldly declared that women have strong sexual urges and to pretend otherwise is folly—a shocking sentiment for the time, even more so because it came from the hand of a female author. In his candid biography of her, Godwin confirmed that she had never married Imlay, the father of her first daughter. (When she and Imlay were together, she often pretended they were married for the sake of social convenience.) Being an unwed mother was a deep mark of shame, and her work was relegated to the brink of obscurity for decades until rediscovered by American suffragists. Grieving her death, a wounded Godwin reflected on the brief, thirty-eight-year tenure of his wife upon the earth: “This light was lent to me for a very short period, and is now extinguished for ever!”

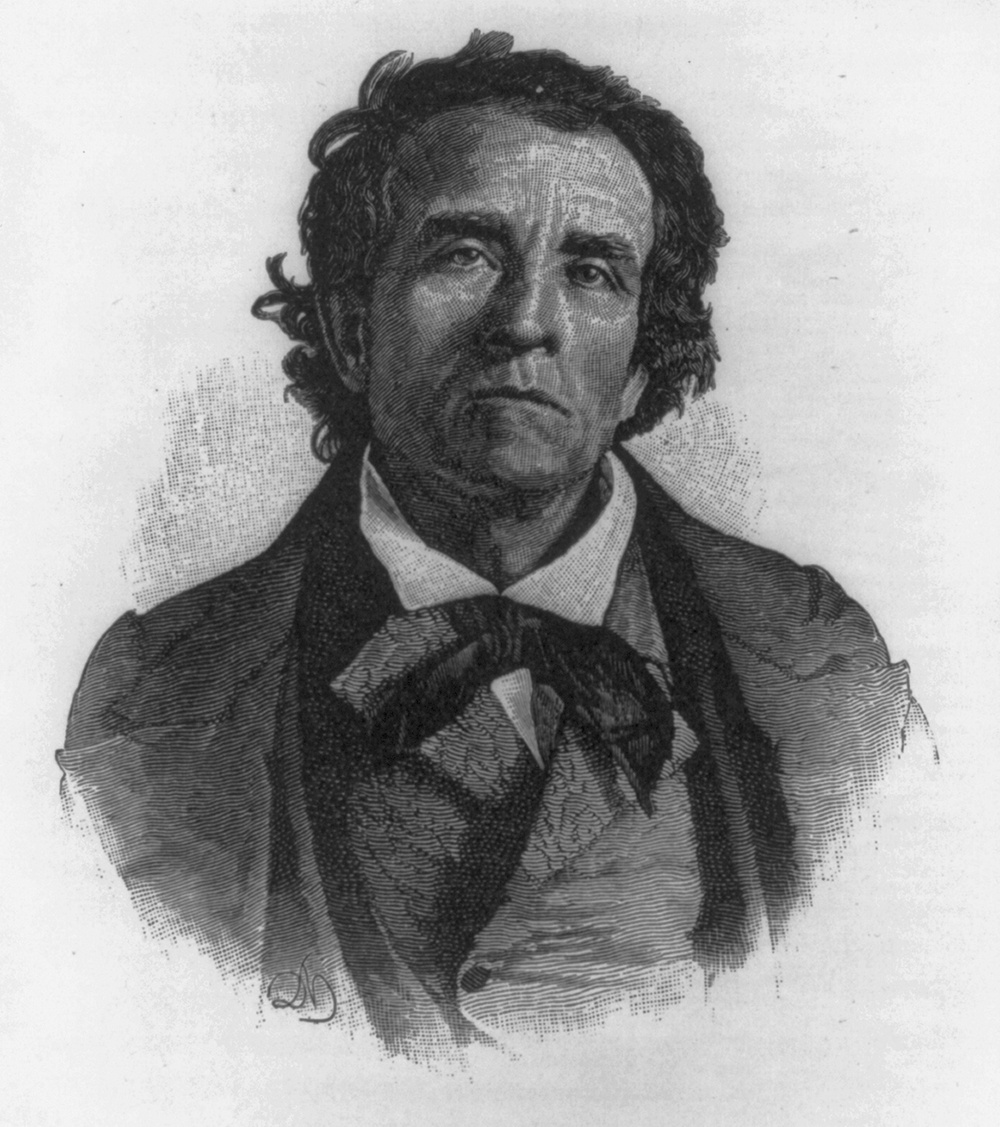

Angelina Grimké and Theodore Weld | Anniversary: May 14, 1838

Two American readers of Wollstonecraft’s writing were the Grimké sisters, Angelina and Sarah. Born in South Carolina to a slave-owning state supreme court judge, the sisters were the rare abolitionists who had seen the horror of slavery firsthand, and they were the first to make a correlation between slavery and women’s status in society. They also believed—inspired by Wollstonecraft—that there were no inherent inferiorities in either women or slaves but rather that a lack of education prevented them from living up to their full intellectual capacities. Angelina said in 1863:

I rejoice exceedingly that that resolution would combine us [women] with the negro. I feel that we have been with him…True, we have not felt the slaveholder’s lash; true, we have not had our hands manacled, but our hearts have been crushed…I want to be identified with the negro; until he gets his rights, we shall never have ours.

The sisters educated themselves in the family library because their father believed formal education was a privilege only for men. Angelina defied the law by teaching slaves to read and write while Sarah studied Latin and jurisprudence, though she had no hope of practicing because law was a male-only occupation. As adults, the sisters moved from Charleston to Philadelphia and became devout Quakers, alienating themselves completely from their Southern past. They supported the Underground Railroad and were the first women to lecture publicly about feminism and abolition in “promiscuous” crowds of both blacks and whites, women and men. Angelina developed a reputation as an enthralling speaker; Sarah, though an excellent writer, lacked her sister’s charisma. Yet nothing drove a wedge between the two sisters, who were a package deal.

The sisters had mixed feelings about marriage, viewing the laws of coverture as a means of enslavement. Sarah echoed Wollstonecraft in her famous Letters on the Equality of the Sexes:

That the laws which have been generally adopted in the United States, for the government of women, have been framed almost entirely for the exclusive benefit of men, and with a design to oppress women, by depriving them of all control over their property, is too manifest to be denied…Men, in the exercise of their usurped dominion over women, have almost invariably done one of two things. They have either made slaves of the creatures whom God designed to be their companions and their coadjutors in every moral and intellectual improvement, or they have dressed them like dolls, and used them as toys to amuse their hours of recreation.

Despite her matrimonial misgivings, Angelina agreed to marry Theodore Weld during the Anti-Slavery Convention of American Women in Philadelphia in May 1838. Weld, a well-known orator, was considered the philosophical and moral center of the radical abolitionist movement. For abolitionists, this was the wedding of the century.

Angelina and Theodore wanted a civil marriage that did not involve a priest. According to Pennsylvania state law, they could be legally wed in the presence of twelve witnesses and one justice of the peace, with a contract signed by the bride, groom, and witnesses. The eighty people who attended the ceremony included the abolitionists Gerrit Smith, John Brown’s financial backer; William Lloyd Garrison, editor of abolitionist paper The Liberator; Henry B. Stanton, who would later marry Elizabeth Cady; and Lewis Tappan, who won freedom for the enslaved Africans of the Amistad. There were both black and white guests, including two freed slaves who had been owned by the Grimkés’ father, and the couple were blessed by both black and white ministers. A wedding cake was ordered from a black confectioner who used only free-grown sugar instead of slave-grown sugar. The bride and groom’s improvised vows were progressive even by today’s standards. Theodore acknowledged the “unrighteous power vested in a husband by the laws” and renounced any authority given to him by unjust laws, promising to cherish “the influence love would give to them over each other as mortal and immortal beings.” Angelina vowed to “honor” her husband—a departure from the traditional vow of obedience—and “to love him with a pure heart fervently.” Able to contain herself no longer, Sarah began praying to bless the couple, effectively ending the ceremony.

The backlash to their ceremony was swift and brutal. Both Grimké sisters were excommunicated from the Quaker faith: Angelina for marrying outside the religion and Sarah for attending the wedding. Angelina’s enemies nicknamed her “Devilina.” Pennsylvania Hall, the site of the Anti-Slavery Convention, was burned to the ground three days later while the city of Philadelphia frothed with anxiety over a rumor that the Grimké-Weld union had been a mixed-race wedding. The convention was one of the last times either sister would speak publicly.

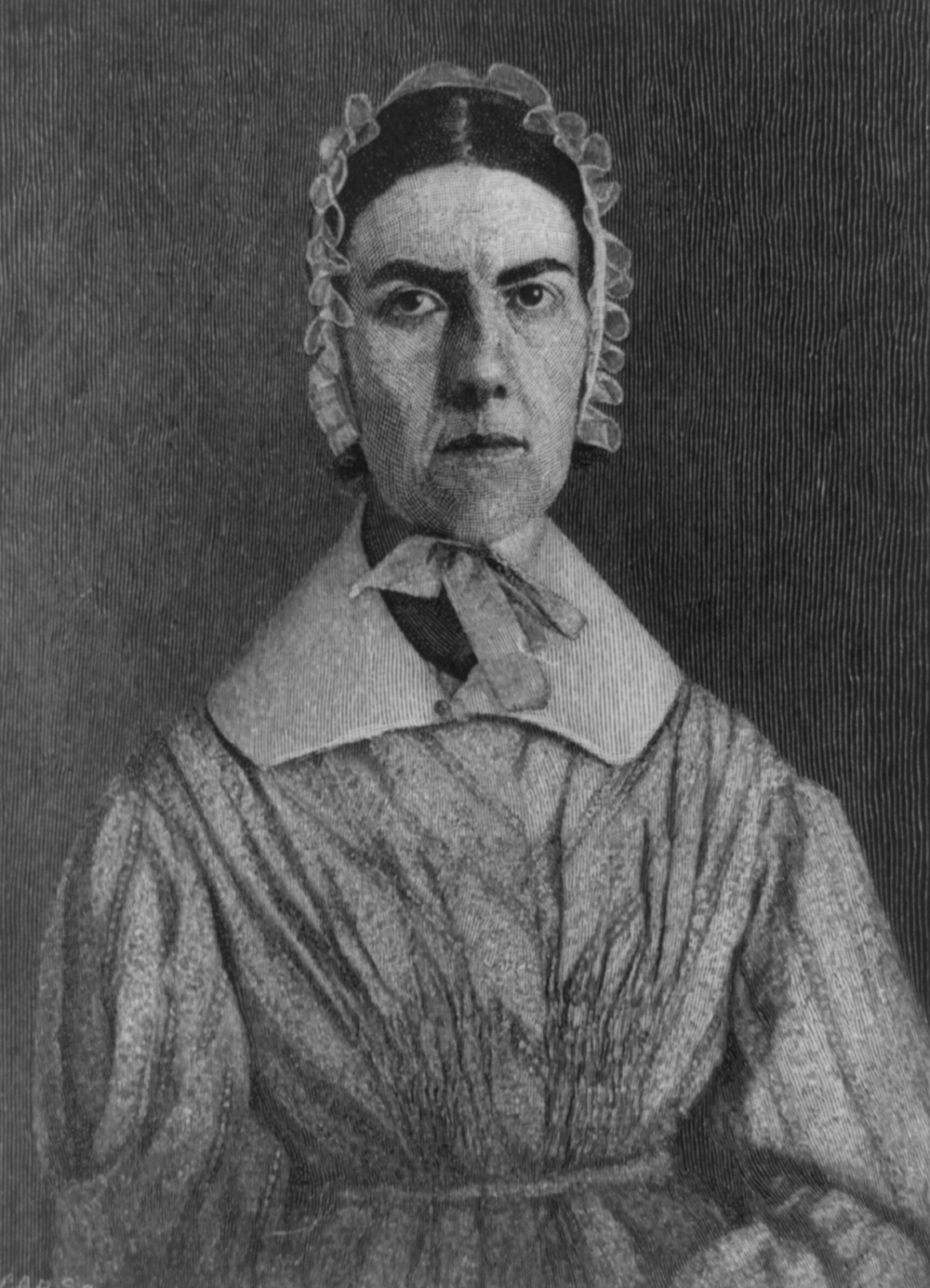

Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Henry Brewster Stanton | Anniversary: May 11, 1840

In 1890, at the age of seventy-five, American suffrage leader Elizabeth Cady Stanton visited the graves of Mary Wollstonecraft and William Godwin, who were buried in the seaside town of Bournemouth, England, alongside their daughter, Mary Shelley. Stanton’s own life work as a suffragist was rooted in Wollstonecraft’s writings; she had long insisted that women were rational beings with an equal right to participation in public life. Rather than arguing for women’s rights from an ethical perspective, Stanton focused on the law itself, calling marriage “legalized prostitution” and analyzing how it was designed to enforce the inequality between the sexes. The afternoon she spent at her predecessor’s grave was heavy and introspective, as she looked back at her own successes and disappointments, contemplating the transience of life while “reading and thinking of the Shelleys, watching the changing hues of the clouds and the beautiful bay, and listening to the sad monotone of the waves.”

Stanton’s exposure to the injustices married women faced under the law began decades earlier. Born into a rich and well-connected family, her father was an attorney and law professor and later a member of Congress and New York Supreme Court judge. His office was attached to the family home, and young Elizabeth spent many afternoons there, listening to the complaints of women seeking her father’s legal advice and beginning to understand the “injustice and cruelty of the laws.” She heard stories from women who had brought all their property into a marriage only to discover after their husbands’ deaths that everything had been willed to their male heirs; the widows were subject to the mercurial whims of their sons (and often uncongenial daughters-in-law). Her father’s students saw she was curious about the laws affecting women and would tease her by reading her the worst ones. One Christmas, eleven-year-old Elizabeth showed one of the students her new coral necklace and bracelet, and he taunted her:

Now, if in due time you should be my wife, those ornaments would be mine; I could take them and lock them up, and you could never wear them except with my permission. I could even exchange them for a box of cigars, and you could watch them evaporate in smoke.

Being a child and not understanding why laws written in books held such power, she resolved to sneak into her father’s office and cut out the offending passages. Catching wind of her plan, her father explained how laws worked (unfortunately, they were printed in more than one book) but encouraged her:

When you are grown up, and able to prepare a speech, you must go down to Albany and talk to the legislators; tell them all you have seen in this office—the sufferings of these [women], robbed of their inheritance and left dependent on their unworthy sons, and, if you can persuade them to pass new laws, the old ones will be a dead letter.

He set into motion the course of her career, as she would be the foremost suffragist to challenge the laws directly and ensure new ones were written.

Elizabeth was one of five sisters, and her siblings all married attorneys and students of her father. Ever the contrarian, Elizabeth fell in love with abolitionist orator and attorney Henry Brewster Stanton. Her father disliked him as a suitor, believing him incapable of providing a sufficient income to support a family. She married him anyway, only later to discover her father’s premonitions were accurate and Henry had no talent for earning money. Henry had been the best man at Theodore Weld and Angelina Grimké’s wedding; like Angelina, Elizabeth eschewed the traditional vow of obedience at their wedding. They married in a modest ceremony on a Friday—traditionally a day for bad luck in marriages—and while neither was superstitious, their union nonetheless was not a happy one.

Things went wrong almost immediately. They honeymooned at the World’s Anti-Slavery Convention in London, where Elizabeth was outraged that women, including Lucretia Mott and the Grimké sisters, were sidelined and not permitted to speak. She and Mott spent the convention discussing Wollstonecraft’s ideas, and Elizabeth began forming a plan to change the laws for women. She wanted not only suffrage for women but also more equitable divorce laws: women were permitted divorces only in cases of adultery (a law that did not change in New York until 1967) and were not granted custody of their children. She did not believe in the abolition of marriage—nor did she believe divorce was a foe of marriage—but wanted the union to be a meeting of equals.

Following the honeymoon, she and Henry moved to Boston. Elizabeth loved the city, but her husband felt like a small fish in a big pond and insisted they move to the smaller town of Seneca Falls, New York. Her disappointment in the union grew when he began leaving home for months at a time, expecting her to fulfill the traditional duties of household management and rearing their seven children. Elizabeth continued to write and lecture tirelessly, leaning on suffragist friends such as Mott and Susan B. Anthony for emotional support and intellectual companionship. Distraught over the institution of marriage and now with firsthand knowledge of its shortcomings, she spent the next forty years advocating for more liberal divorce laws. In 1884, she published an article in response to a judge who wished to universally ban divorce:

The decisions of judges in many cases show that the subjection of woman is the very essence of the law of marriage; and how could it be otherwise when the contract and all the statutes governing it have been made by one of the parties, while the other has been profoundly ignorant of its provisions and specifications. How many women in this republic know anything of the spirit or letter of the civil or canon law on this whole question of marriage and divorce? Not until they feel its iron teeth in their own flesh do they awake to the helplessness of their position…In all history, sacred and profane, woman has never been recognized as an equal party to the contract.

Her efforts helped pass the Married Women’s Property Act in New York in 1848, partially overturning the laws of coverture and allowing women to maintain ownership of their property both during and after marriage.

Beyond just changing the laws, she wanted women in all walks of life to be more self-reliant and to overthrow the concept of the feme-covert, hidden within the identity of a man. “No matter how much women prefer to lean, to be protected and supported, nor how much men desire to have them do so, they must make the voyage of life alone, and for safety in an emergency they must know something of the laws of navigation,” she wrote in 1892.

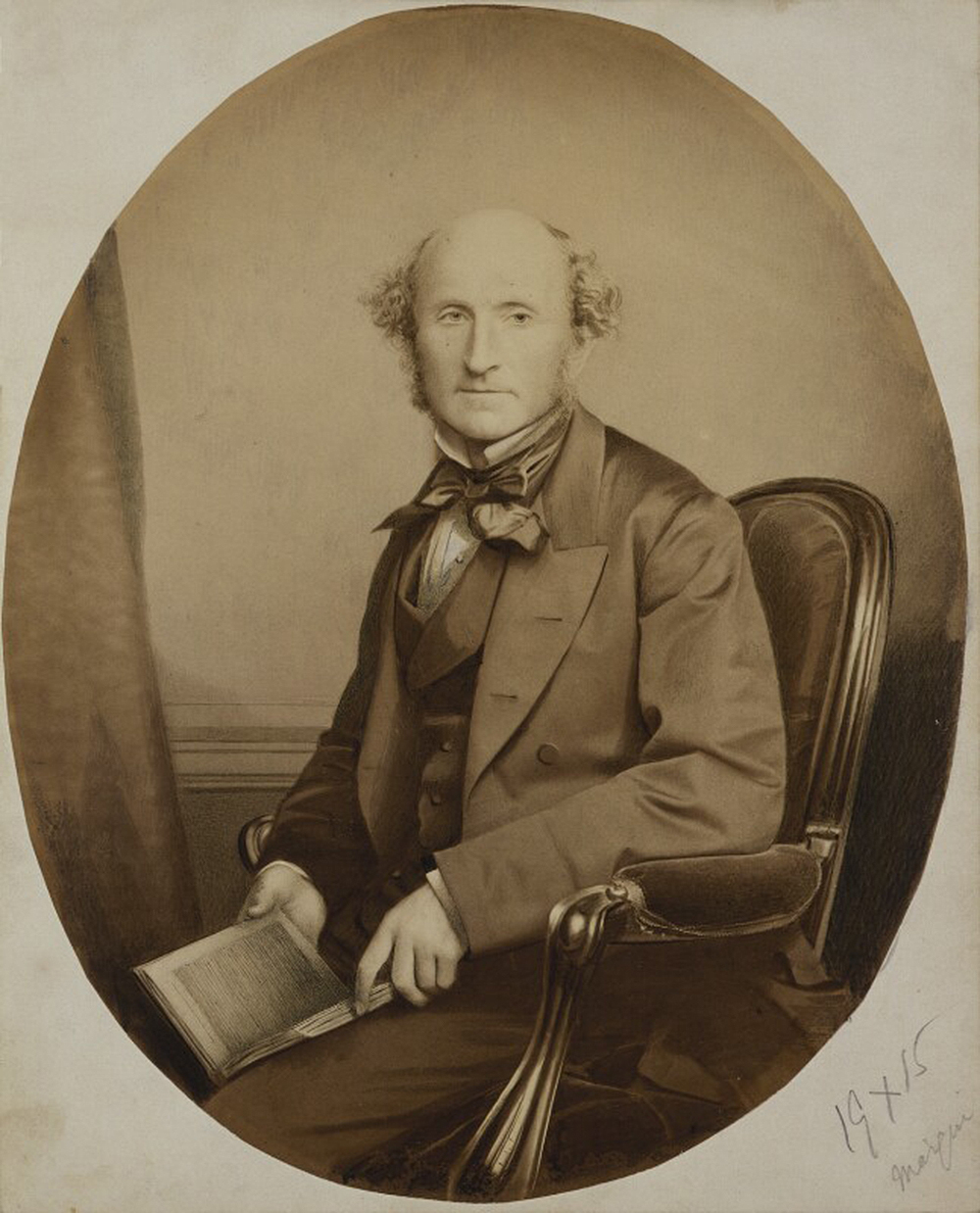

John Stuart Mill and Harriet Taylor Mill | Anniversary: 1851

British abolitionist and feminist John Stuart Mill was so wildly ahead of his time that his work still reads as progressive nearly two centuries later. Both his father James Mill and tutor Jeremy Bentham were contemporaries of William Godwin, all of whom are considered founders of utilitarianism and “Happiness Philosophers.” The older Godwin was more eccentric, curmudgeonly, and intentionally controversial than John Stuart Mill, who was charming and intellectually fluid. But both writers shared several similar beliefs: people are fundamentally rational, marriage in its current form is evil, women deserve complete parity with men in every walk of life.

Mill was a supporter of partnerships but an opponent of marriage laws. “If all, or even most persons, in the choice of a companion of the other sex, were led by any real aspiration towards, or sense of, the happiness which such companionship in its best shape is capable of giving to the best natures,” he wrote, “there would never have been any reason why law or opinion should have set any limits to the most unbounded freedom of uniting and separating.”

That women did not have freedom of choice inspired the scathing essay “The Subjection of Women” in 1869. His argument was that women were forced into marriage out of economic necessity and then found themselves in a state in which they had no rights—no rights to own property, to bodily autonomy, to earn a living, to custody of their own children—and because divorce was illegal, they never had an opportunity to make a better match if their first union was ill-made. The impossibility of divorce was, for Mill, the most odious problem with marriage laws. If women had only one option open to them, they should be able to revise their choice until they arrived at the suitable one. Without the option of divorce, women were made slaves under the law.

The wife’s position under the common law of England is worse than that of slaves in the laws of many countries…The two are called “one person in law,” for the purpose of inferring that whatever is hers is his, but the parallel inference is never drawn that whatever is his is hers; the maxim is not applied against the man, except to make him responsible to third parties for her acts, as a master is for the acts of his slaves or of his cattle…Since everything in the woman’s life depends on her obtaining a good master, she should be allowed to change again and again until she finds one…those to whom nothing but servitude is allowed, the only lightening of the burden (and a most insufficient one at that) is to allow a free choice of servitude.

His argument was similar to the one made by the Grimké sisters—in fact, at age seventy-seven, Sarah Grimké walked around her New Jersey neighborhood selling copies of his book.

Like Godwin, Mill was astute enough to see the inequality inherent in marriage; also like Godwin, this awareness did not prevent him from falling in love and wanting to express that love through marriage. Not that Mill had either a typical courtship or a typical wife. Members of the same Unitarian church, Mill and the philosopher and women’s rights advocate Harriet Hardy Taylor met in 1830, when Harriet was already married with three young children. The two had a public affair for the next twenty years, with Harriet moving out of her husband’s home and living independently in order to be closer to Mill. Although the community shunned the adulterous lovers, her husband was remarkably tolerant of the relationship. Mill and Taylor found intellectual companionship with one another and collaborated frequently, including on Mill’s most famous work, “On Liberty,” published in 1859.

Taylor published “The Enfranchisement of Women” under his name in 1851, in which she argued—taking a more radical stance than Mill—that women should have the same access as men to education and jobs so that a woman’s intelligence would not be limited by her existence in a separate sphere. She wrote with the understanding of someone who knew the pitfalls of marriage intimately:

The most insignificant of men, the man who can obtain influence or consideration nowhere else, finds one place where he is chief and head. There is one person, often greatly his superior in understanding, who is obliged to consult him, and whom he is not obliged to consult. He is judge, magistrate, ruler, over their joint concerns.

Mill and Taylor married the same year that “The Enfranchisement of Women” came out, two years after her husband died. To commemorate their union, they published a beautiful joint essay on the virtues of love, companionship, and self-reliance—and of course they took the opportunity to hold marriage laws in contempt. “Surely it is wrong, wrong in every way, and on every view of morality, even the vulgar view—that there should exist any motives to marriage except the happiness which two persons who love one another feel in associating their existence,” Mill wrote in his essay in response to women who were forced into marriage for economic survival. His wife echoed this sentiment in her contribution, longing for a society in which women were self-reliant. She asked:

At this present time, in this state of civilization, what evil could be caused by, first placing women on the most entire equality with men, as to all rights and privileges, civil and political, and then doing away with all laws whatever relating to marriage?

Lucy Stone and Henry Blackwell | Anniversary: May 1, 1855

Lucy Stone is the most famous suffragist whose name is virtually unknown today. She was part of a women’s rights triumvirate alongside heavyweights Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony but had a dramatic falling-out with them after the passage of the Fifteenth Amendment, which extended suffrage to black men but not women. Stone believed in universal equality and thought women would be next in line for suffrage after the inclusion of black men, so she supported the amendment; Stanton and Anthony were alarmed by the Constitution explicitly stating that voting rights were a male privilege, for women had previously been barred from voting only at the state level. (Stanton said, “If that word ‘male’ be inserted, it will take us a century at least to get it out.”) Stanton and Anthony were the movement’s historiographers, and not incidentally Stone’s influence was omitted from their records.

Lucy Stone was the first woman from Massachusetts to earn a college degree, as well as the first woman in the United States to keep her own name after marriage. She became known as the greatest female orator of her era and lectured about feminism and equality along race, gender, and class lines. Crowds pelted her with rotten fruit and cold water because she was a woman and because her message was radical. Like other early feminists, she viewed marriage as an unequal union and remained single, believing her career and autonomy would be sacrificed to the whims of a husband or the laws that restricted the ambitions of married women. In an 1855 speech, she said:

In education, in marriage, in religion, in everything, disappointment is the lot of women. It shall be the business of my life to deepen this disappointment in every woman's heart until she bows down to it no longer.

Despite her intention never to marry, she did have one very persistent suitor, an abolitionist named Henry Blackwell, part of the large, prosperous, and influential Blackwell clan. Henry’s brother was married to Antoinette Brown, Lucy’s best friend from college and the nation’s first female minister. Henry’s two sisters were the remarkable Elizabeth and Emily Blackwell, the country’s first and third female physicians, respectively. Elizabeth, the elder sister, had graduated first in her class at medical school and chose not to marry because it would be a hindrance to her career; Emily also did not marry and spent her life with a female companion. Perhaps Henry Blackwell would be the iconoclastic and intellectual companion able to change Lucy Stone’s mind about matrimony.

Blackwell’s journals show he was deeply in love with her, awed by her intellect and public speaking skills, beaming with pride at the success of her lectures that she routinely delivered to sold-out audiences. Stone, however, was stubborn and remained a staunch opponent of the laws that made men masters over their wives. She was determined to live independently and without a man’s financial support. In their letters, they debated over divorce, child custody, suffrage, a women’s right to independence, and more. Blackwell pursued Stone for two years, employing every tactic a determined suitor has at his disposal until she was convinced of his pure intentions. One of his beautifully written letters asks if she is refusing marriage because she truly does not want a partner or if perhaps her hostility toward the laws is preventing her from experiencing love and companionship:

While I do not believe one word of the poetical fiction that any two human beings are constituted particularly and in all respects fitted for each other—perfect counterparts, capable of a mystical and absolute union—I do believe that certain temperaments, tastes, and dispositions naturally attract or repel each other, and that we are so constituted that we need to form an alliance, the most pure and intimate possible, with one individual of the opposite sex. Although the ideal of marriage, as everything else, can only exist in possibility…I still believe that the majority of the people may, and many do, realize on earth a union more beautiful and desirable than any other which the present stage of the world’s development permits. To undertake that relation is equally a privilege and a duty. To conceive oneself precluded from assuming, because the existing laws of society do not square with exact justice, is to subject oneself to a more abject slavery than ever actually existed. Will you permit the injustice of the world to enforce upon you a life of celibacy? The true mode of protest is to assume the natural relation and reject the unnatural dependence.

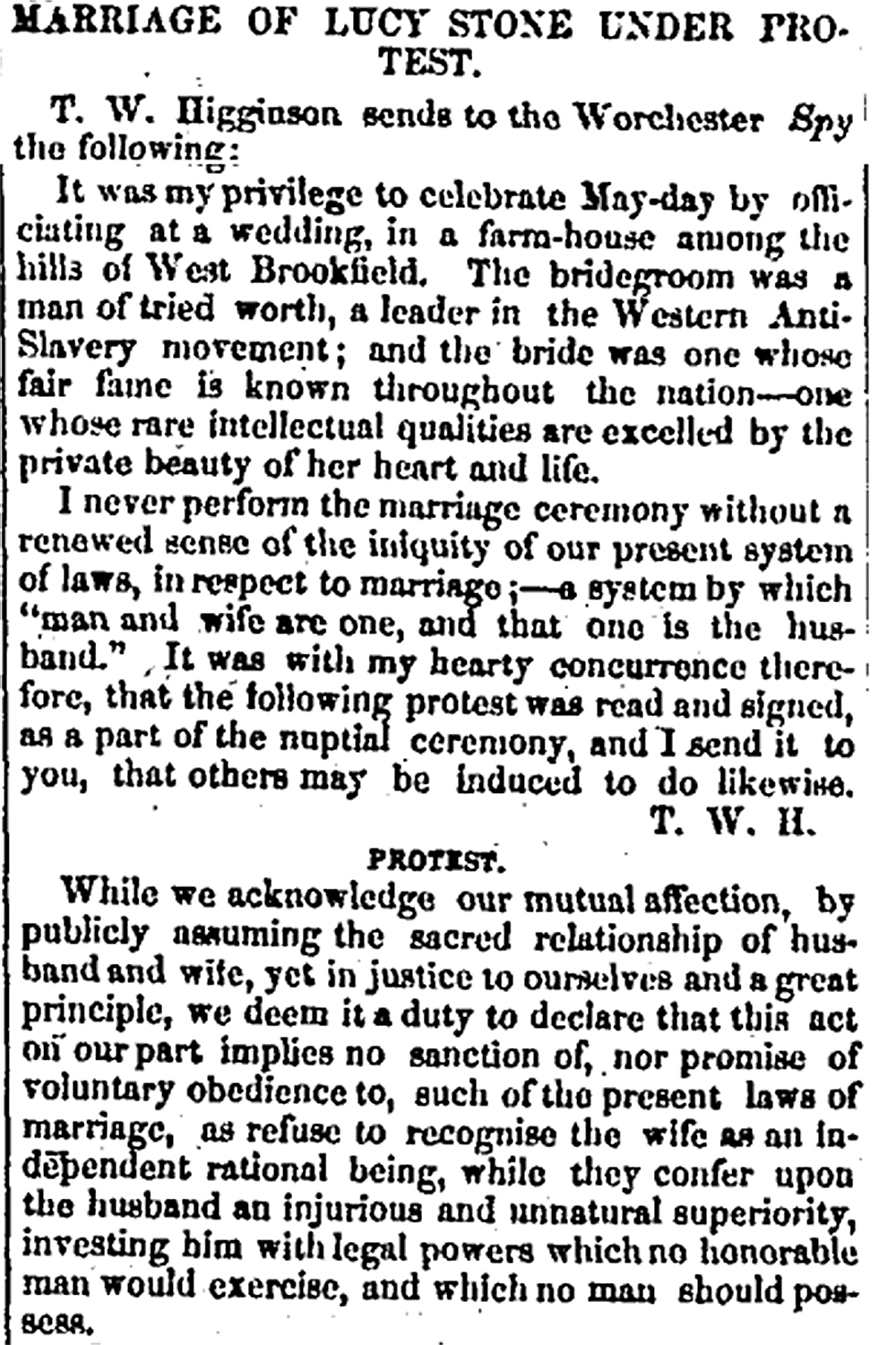

Lucy Stone and Henry Blackwell were married on May 1, 1855. The ceremony was performed by the remarkable Reverend Thomas Wentworth Higginson, a graduate of Harvard Divinity School and Unitarian minister whose viewpoints on social reform were, somewhat incredibly, too liberal even for Unitarians, causing him to lose his congregation. (Worth noting: he was the man to whom Emily Dickinson submitted her first poems to Higginson, and he warmly encouraged her to continue writing. Following her death, he edited the first two volumes of her work.) About their wedding, Higginson said, “I never perform a marriage ceremony without a renewed sense of the iniquity of our present system of laws in respect to marriage; a system by which ‘man and wife are one, and the one is the husband.’ ”

Stone and Blackwell wrote the following marriage protest, which was read aloud at the ceremony and later published widely throughout the nation:

While we acknowledge our mutual affection by publicly assuming the relationship of husband and wife, yet in justice to ourselves and a great principle, we deem it a duty to declare that this act on our part implies no sanction of, nor promise of voluntary obedience to such of the present laws of marriage, as refuse to recognize the wife as an independent, rational being, while they confer upon the husband an injurious and unnatural superiority, investing him with legal powers which no honorable man would exercise, and which no man should possess. We protest especially against the laws which give to the husband:

1. The custody of the wife’s person.

2. The exclusive control and guardianship of their children.

3. The sole ownership of her personal, and use of her real estate, unless previously settled upon her, or placed in the hands of trustees, as in the case of minors, lunatics, and idiots.

4. The absolute right to the product of her industry.

5. Also against laws which give to the widower so much larger and more permanent interest in the property of his deceased wife, than they give to the widow in that of the deceased husband.

6. Finally, against the whole system by which “the legal existence of the wife is suspended during marriage,” so that in most States, she neither has a legal part in the choice of her residence, nor can she make a will, nor sue or be sued in her own name, nor inherit property.

We believe that personal independence and equal human rights can never be forfeited, except for crime; that marriage should be an equal and permanent partnership, and so recognized by law; that until it is so recognized, married partners should provide against the radical injustice of present laws, by every means in their power.

Read more on law and life in our Spring 2018 issue, Rule of Law.