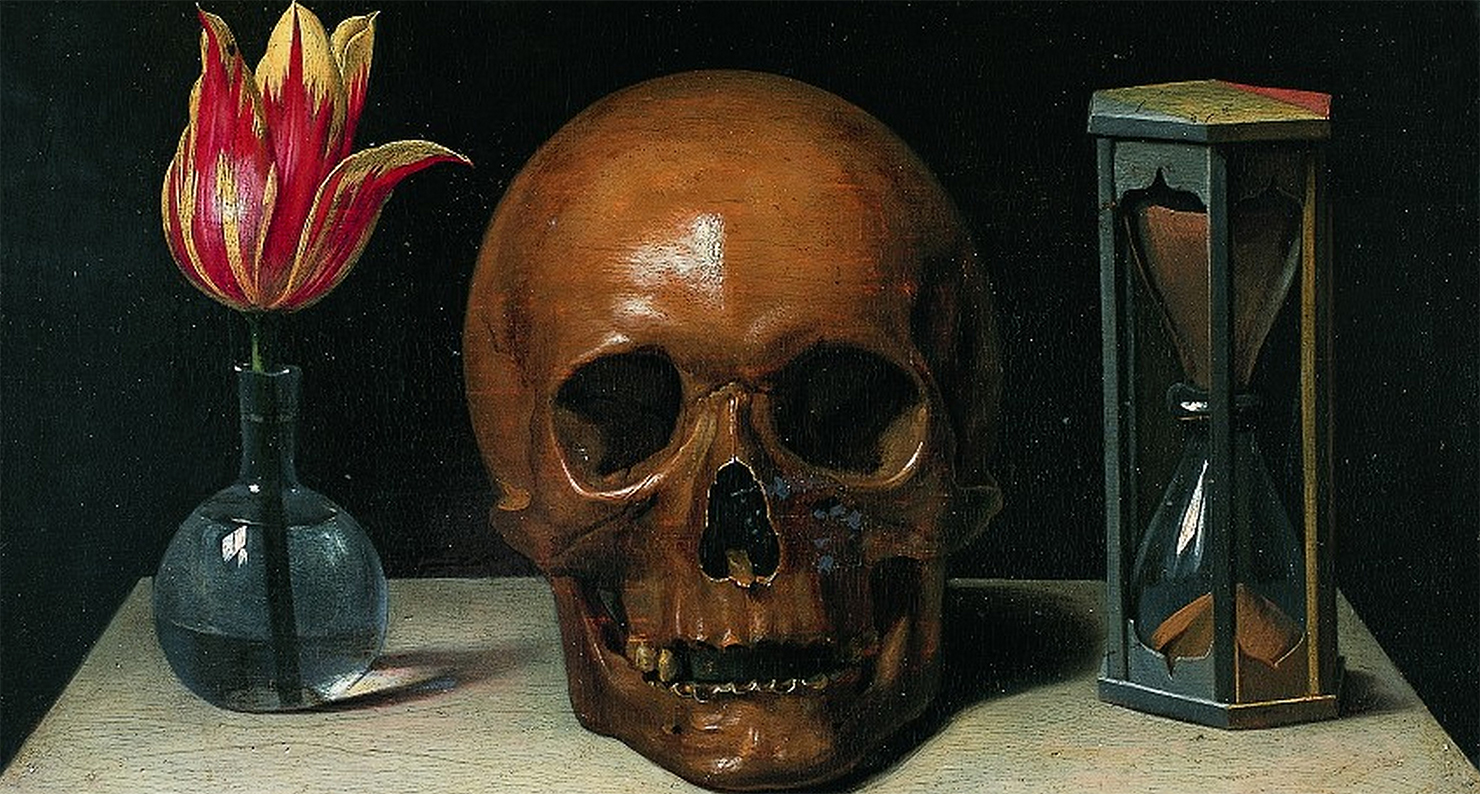

Vanitas Still Life with a Tulip, Skull and Hour Glass, by Philippe de Champaigne, c. 1671. Tessé Museum, Le Mans, France.

Ithe candlelit shadows of Georges de La Tour’s The Repentant Magdalene, the saint contemplates the mirrored reflection of a human skull while her fingers play over the bone. Memento mori—she seeks to remember that she will die.

Given all she’s seen, at Golgatha and elsewhere, it’s odd to think she could ever forget. People do, though.The mortal awareness of those medieval monks who slept in their coffins might not have lasted through breakfast. But then a bell tolled.

The rationale of the memento mori tradition is that we’ll commit fewer sins, waste less time, if we remember our end. That we won’t be such jerks. “Depend upon it, sir,” says ever-dependable Samuel Johnson, “when a man knows he is to be hanged in a fortnight, it concentrates his mind wonderfully.”

Buddha, all-time hero of the concentrated mind, seems to agree. “Before long, alas! This body will lie on the ground, despised, bereft of consciousness, like a useless log.” It might be said that religion grew out of a heightened sense of mortality and then endeavored to plant the seed from which it grew.

I use the past tense for a reason. Digital fundamentalism, arguably our closest contemporary approximation to “the one true faith,” discourages memento mori through virtual disembodiment—we are our information and the information never dies—and through biotech fantasies of everlasting life.

Traditional faiths often do no better. It’s possible to go to a church funeral nowadays only to find that death has not been invited. Perhaps for that same reason, neither has resurrection. Sitting in their places is a vapid cant about “memories” and “a better place,” the latter likened to a golf course, the drinks menu at a Starbucks, “whatever you want it to be.”

“Remember, O man, that thou art dust and unto dust thou shalt return”—the words spoken during the imposition of ashes at an Ash Wednesday service. Most people skip it and cut straight to the Easter ham. Consumer Christianity forfeits the best of two worlds, it seems to me: the gravitas of Greco-Roman resignation in the face of death, and the alternative gravitas of the Hebraic hope for redemptive transformation.

Doubly bereft in this way, its only recourse is to be silly.

The tradition of memento mori takes on additional weight in a world threatened with environmental disaster. The problem might be stated as follows: How can a person who fails to grasp his own existential condition manage to grasp the larger, more difficultly imagined reality that the earth as we know it could be destroyed?

By “grasp,” I mean to live as if it were really so. I mean to embody what people claimed they heard in Martin Luther King’s speech about the mountaintop, which they might as easily have inferred from any focused observation of his life. “It was as if that man knew he was going to die.” Indeed.

I suppose it could be argued that what I’m driving at here rests on a dubious premise. Isn’t a stark realization of one’s own death just as likely to produce reckless irresponsibility? I’m gonna die some day, so I might as well pull out all the stops now. Forget recycling, baby, it’s party time! I don’t think so.

In fact, “eat, drink, and be merry, for tomorrow we die” is a much more sober formulation than is often supposed. The key is in that lovely and convivial wordmerry—not the first word that comes to mind when I think of spring break or binge-drinking. A Vomiting Christmas to you, and a Happy New Year? Again, I don’t think so.

Merriment grows out of the felt awareness that one will die, that all will die. It is an adult apprehension. Children can be joyful, even ecstatic; I do not think they are ever merry. “The Son of Man has come eating and drinking, and you say, ‘Look, a glutton and a drunkard, a friend of tax collectors and sinners.’” I say, look, a son of man who knows how to be merry. A son of man who knows he is going to die.

“I must do the work of the one who sent me while it is day. The night is coming when no one can work.” And quite possibly a day when it will be too hot to work.

Whenever I hear the expression “global-warming deniers” I don’t think of dissenting climate scientists or Republican congressmen in bed with Big Coal. The most vociferous deniers of global-warming, and the most dangerous, are in fact those who affirm it. “We are facing the greatest environmental catastrophe in the history of humankind,” they say, boarding a plane to Kyoto. The man on the ground says, “I don’t believe you. And I don’t believe you because you’re boarding a plane to Kyoto.”

Not long ago I had a brief email exchange with an environmental activist whom I greatly respect, whose money is always where his mouth is. He’d invited me to a protest against the proposed Keystone Pipeline. In the course of begging off, I mentioned being troubled by the carbon footprint of those traveling to the demonstration. His response, as nearly as I can recall, was that we were past the point where individual renunciations of the kind I was suggesting could be of much use. The crisis had reached a level where nothing less than a radical shift in national policy could save us.

He was absolutely right, of course, though his response begged the question of how such a shift can be effected. Short of a violent seizure of power, such a shift will come only when our politicians—who wouldn’t shell a peanut without first taking a poll—see an electorate actually living as though it believed that the world it knows and loves could die. In other words, renunciation isn’t beside the point. It is the point.

The measure of what an elected official might be willing to do to address global climate change will be determined by the sacrificial witness of those who elected him. In the absence of such witness, an elected official rightly assumes that the only thing likely to wind up on an altar is his career.

A thousand people chained to a pipeline will not greatly change that perception. It’s not so much that the leader feels he can afford to lose a thousand votes as that he knows that once the protest is over, a thousand people are going to want a direct flight home followed by a nice long shower. If he can keep the planes flying and the hot water running at roughly the same rate as the greenhouse gas of his empty rhetoric, he knows he has nothing to fear.

I suppose that I, too, am begging a question, which is how one can attain a consciousness of memento mori and give it an environmentalist spin. I wish I knew. I doubt very much that such a thing can be achieved through stridency or accompanied by stridency. “And those that build them are gay,” writes William Butler Yeats in “Lapis Lazuli,” meaning those who make civilizations. His words might also apply to those who save ecosystems. Of course, he means “gay” solely in the sense of attitude; there’s a good reason no one teaches this poem in high school.

I wonder, though, if we would do well to add the extra denotation to Yeats’s line. In other words, I wonder if the tradition of memento mori exists more vividly in the remnants of the gay community than in any remaining monastic tradition. From those who have lived daily in the shadow of AIDS, we may be able to learn something about that complex ethos of care-giving, self-denial, and mortal merriment without which environmentalism has about the same chances of survival as the polar bears do.