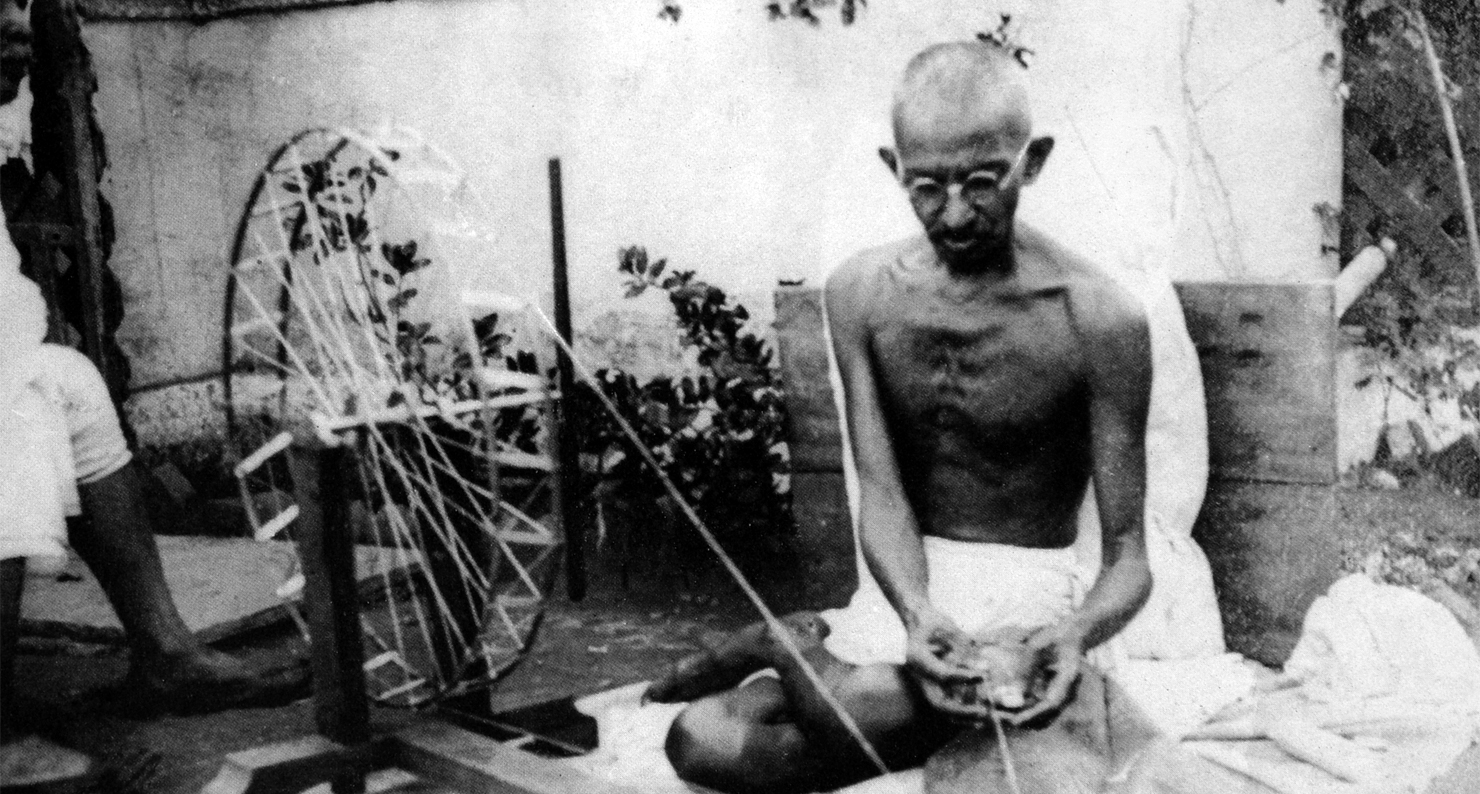

Mahatma Gandhi spinning yarn in the late 1920s. Wikimedia Commons.

The watch never left his side. It was the first thing Gandhi reached for when he rose each morning at 4 a.m., and the last thing he checked before going to bed, often past midnight. He consulted it frequently through the day so as never to be late for an appointment. And, at that final moment, when three bullets from an assassin’s Beretta knocked him over, his 78-year-old body slumped to the ground, and the watch also stopped.

Mahatma Gandhi’s Ingersoll pocket watch, costing just a dollar, was among the handful of material possessions he owned. Since he didn’t have a pocket to carry it in, he attached the watch to his dhoti with a safety pin and a loop of khadi string. The Ingersoll is displayed in a glass case at the National Gandhi Museum in New Delhi alongside his bloodstained dhoti and shawl. Together, the three items form a striking metaphor of Kala, the Hindu god of time who is also the god of death.

Gandhi’s legendary punctuality had a utilitarian imperative—without it he would never have been able to answer the sacks of letters and streams of visitors that demanded his attention each day. But, as with everything he valued, it had a moral imperative as well. Simply put, time was tied to his philosophy of trusteeship: the belief that just as we do not own our wealth but are trustees of it—and thus have to use it wisely—similarly, we are trustees of our time. “You may not waste a grain of rice or a scrap of paper, and similarly a minute of your time,” he wrote. “It is not ours. It belongs to the nation and we are trustees for the use of it.” Consequently, any abuse of time was unethical. “One who does less than he can is a thief,” he wrote to a friend. “If we keep a timetable we can save ourselves from the last-mentioned sin indulged in even unconsciously.” While this focus on punctuality may portray Gandhi as skittish and anxious, the opposite was true: a timetable allowed him to give the issue at hand his tranquil and undivided attention.

Known to apologize if he was even a minute late, Gandhi was equally stringent about his personal regimen. Winding up a letter to a professor, he wrote: “I am also being reminded by Lady Watch that it is time for my walk. So I obey her and stop here.” Apparently, even the British police knew about Lady Watch. After Gandhi relaunched the civil disobedience movement in January 1932, the Bombay commissioner of police showed up at three in the morning to arrest him. Gandhi, who was still asleep, sat up to hear the commissioner say, “I should like you to be ready in half an hour’s time.” Instinctively, he reached under his pillow, and the commissioner remarked, “Ah, the famous watch!” Both men began to laugh. Then Gandhi picked up a pencil—it was his weekly day of silence—and wrote, “I will be ready to come with you in half an hour.”

Barely a few days before his arrest, Gandhi had sent two English watches as thank-you gifts to the Scotland Yard sergeants assigned to detail him during his stay in London for the 1931 Round Table Conference. The inscription read: “With love from M. K. Gandhi.” Much thought had gone into the gift. The sergeants, who used to rise with Gandhi in the morning and travel everywhere with him, knew firsthand how the slender hands of the clock ruled his day. The gift of a watch from him thus had a special significance. In addition, Gandhi chose English rather than the more easily available Swiss-made watches to convey the message that, despite his campaign to boycott British cloth, he bore no ill will to the British people. When his friend the Anglican missionary C. F. Andrews had objected strongly to his bonfires of foreign cloth, Gandhi took great pains to point out it was only foreign mill-made cloth he was against since it had destroyed India’s spinners and weavers. “If the emphasis were on all foreign things it would be racial, parochial, and wicked,” he wrote. “The emphasis is on foreign cloth. The restriction makes all the difference in the world. I do not want to shut out English lever watches.”

During his stints in jail as a prisoner of the Raj, Gandhi would often write more than fifty letters a day—even when his thumb and elbow ached—in addition to spinning, reading the Gita or works by John Ruskin, learning Urdu, cooking, and cultivating his passion for astronomy. His secretary Mahadev Desai marveled at his use of time. Gandhi’s letters are brisk (like his walk) and often acerbic, but also intimate and full of concern—especially for the way people spent their time. What time do you wake up in the morning? he’d ask. Or, in a slightly hectoring reminder to the women of the ashram, “It is now five to seven; you are therefore all on your way to the prayer hall.” Or, in a guilty self-check when he had written a longer than usual letter, “I must not give you more time today.” Outside jail, he had far less time, so the letters became shorter. To those who complained, he replied sharply: “Do not expect letters from me at present. I have no time at all. But you keep writing regularly.”

He was unsparing of tardiness from those around him, even if the offender happened to be a child. On learning that a girl at his Sabarmati ashram had been delayed for the pre-dawn prayer service because she’d been combing her long hair, he sent for a pair of scissors and gave her a bob in the moonlight. His eldest grandson, Kantilal, who was a startled witness to the Barber of Sabarmati in action, didn’t escape either. When the two of them were on a train together, traveling third-class as was the Mahatma’s habit, Gandhi, who was busy writing letters, asked Kanti what time it was, and was told it was five. But the old man’s eyes slanted to the watch on his grandson’s wrist and saw there was still a whole minute to go before five. That was it. The casual glossing over of sixty seconds was treated as a moral lapse:

“He stopped writing and exclaimed: ‘Is it five?’ I replied with a guilty conscience: ‘No, Bapu, it is one minute to five.’ ‘Well, Kanti,’ he said, ‘what is the use of keeping a wristwatch? You have no value of time…Again, you don’t respect truth as you know it. Would it have cost more energy to say: It is one minute to five, than to say It is five o’clock?’ Thus he went on rebuking me for about fifteen to twenty minutes till it was time for his evening meal.”

As is evident from the cheerfully inexact phrase, “about fifteen to twenty minutes,” the young Kanti was unscathed by his grandfather’s critique. He was scarcely alone. Gandhi was fighting a losing battle. Indians have a notoriously relaxed attitude toward punctuality, and as the national joke goes, the abbreviation IST (for Indian Standard Time) should really stand for Indian Stretchable Time. One reason proffered is that the approach to time is fundamentally different. Unlike the Western linear sense of time, Hindu philosophy treats time as cyclical, a concept succinctly illustrated by the sameness of the Hindi word for yesterday and tomorrow—kal. As Salman Rushdie jokes in Midnight’s Children, “No people whose word for yesterday is the same as their word for tomorrow can be said to have a firm grip on time.” But Rushdie also parodies the relentlessly accurate tick-tock of the clock as an “English-made” invention. A similar observation was made by the writer Ronald Duncan, who visited Gandhi’s ashram in 1937. Duncan wrote: “I shall always remember the anachronism of the large cheap watch which dangled on a safety-pin attached to his loincloth: worn this way, time itself appeared to be a toy, an invention of the Western mind.”

According to the novelist R. K. Narayan, the Indian inability to keep time comes from an inborn attitude. Narayan, whose shrewd and gentle stories capture the arrhythmic bustles of small-town India, was unperturbed by a little lateness here and there. “In a country like ours, the preoccupation is with eternity, and little measures of time are hardly ever noticed,” he wrote, adding mischievously that the ideal watch is an ornamental one that prevents you from reading the time.

A new watch designed by an Indian company—called the ish watch—fits the bill. Its odd name parodies the Indian tendency to reply, “Around twelve-ish,” when asked what time a meeting is, or to say, “I made reservations for eight-ish.” The dislocated numbers on its dial capture this elasticity, while the caption reads, “Because in India, time is not science but an art, and we know that art can never be rushed.” Or, to borrow a charming thought from E. M. Forster’s A Passage to India, India is where “adventures do occur, but not punctually.” It’s hardly surprising, then, that Gandhi’s exemplary punctuality is fondly viewed as another of his eccentricities along with mudpacks, enemas, and goat’s milk.

“Keep Time and Carry On” could well have been a Gandhian motto, except that the Mahatma was not very good at keeping time in the literal sense of being able to keep to a beat or maintain a rhythm. As a young law student in London, when he strove briefly and disastrously to be a Western gentleman, Gandhi took six private lessons in ballroom dancing but gave up after he found it “impossible to keep time.” While carding yarn, he complained, “I also keep time in my strokes, but imperfectly.” Part of the young Gandhi’s Western gentleman getup was a gold double-watch chain that he wore prominently on his Bond Street suit. The arc from that pocket-watch to the safety-pin-cum-khadi string Ingersoll parallels the arc from man to mahatma.

Apart from the Ingersoll, the other watch Gandhi loved and wore for almost twenty years was a silver-backed Swiss Zenith given to him by Indira Gandhi when she was a girl. Gandhi admired its functionality—the fact that it had an alarm and a radium dial that glowed at night. So great was his distress when it was stolen at a railway station in May 1947 that he published an appeal in his newspaper, Harijan, asking for it to be returned. Fortunately, the thief—a souvenir hunter—had a conscience, and sent it back.

Meanwhile, however, word had spread about the theft. An English company sent Gandhi a new watch and others offered as well. A gold watch sent by his friend Nand Lal Mehta provoked an outburst against ostentation. “What you have done is like caparisoning a donkey in gold,” Gandhi wrote. (Imagine how scandalized he’d be at the Gandhi 2 Ingersoll, a watch that comes caparisoned in twenty-two jewels.) That Mehta’s watch was merely gilded and not gold, cooled his wrath—barely. “Still I did not like it,” he scolded. “I need only ordinary things. This watch cannot even take a khadi string. It will need a silken string. And because there is no radium on the dial, I shall need a torch or something at night. Of course it is not to be expected that it will have an alarm. This does not mean that you should get a new one.” He concluded grudgingly, “The watch seems to be keeping accurate time.”

The silver Zenith passed into the care of Gandhi’s great-niece, Abha, in whose arms he died. It was auctioned in 2009 along with his slippers, plate, bowl, and spectacles for $1.8 million. That an Indian liquor tycoon, Vijay Mallya, bought it (thus ensuring its return to India) is ironic, given that Gandhi used every available platform to denounce alcohol as satanic. His birthday, October 2, is a dry day in India.

Gandhi was late for his last appointment, his inviolable five o’clock prayer session. On the evening of January 30, 1948, he was so engrossed in a meeting with India’s new home minister, Sardar Vallabhai Patel—who was Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru’s rival—that he forgot the time. His great nieces, Manu and Abha, who were tasked with alerting him, held back, knowing how anguished he was by the rift between his two protégés. When they finally screwed up the courage to interrupt, he rose quickly, went to the bathroom, and then headed out. The interfaith prayer meeting was a crucial form of outreach through which Gandhi met the public and tried to calm the fissile atmosphere in Delhi. The capital of a newly independent India had been engulfed in savage Hindu-Muslim riots and only a fast by Gandhi had stopped the bloodletting. Upset, he hurried forth, saying, “It irks me if I am late for prayers by even a minute.” Minutes later, he was dead, as was his watch—not at “around five” or “five-ish,” but at 5:12, a chronometrically precise salute to the man who loved time.