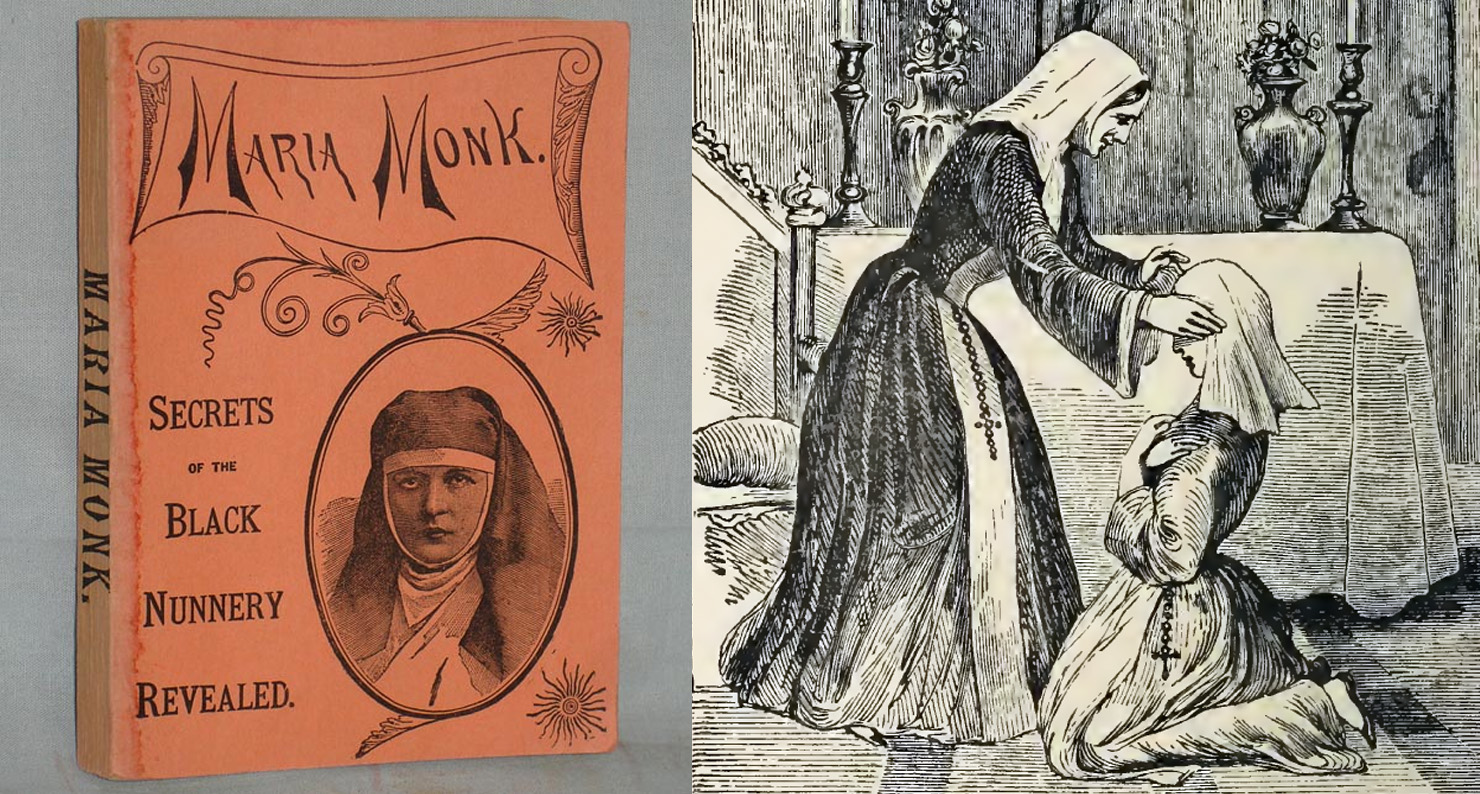

A cover of a facsimile edition of The Awful Disclosures of Maria Monk and an illustrated plate from a different edition. The bestselling book was in print for over seventy years.

Audio brought to you by Curio, a Lapham’s Quarterly partner

In August 1835, Isabella Mills received a strange visit at her home in Montreal. A man whom she had never seen before but who was “decently dressed,” as she’d report later, told her that he had come to the city with her daughter and her daughter’s five-week-old baby. The stranger also told her something that surprised her even more than the news that she had become a grandmother: her daughter Maria, who had not yet turned twenty, had “been in a nunnery”—and she had been very badly treated there.

As far as Mrs. Mills knew, this wasn’t true at all. But later that day, the man, a Protestant minister named William Hoyt, returned with others and they pressed her to accept their story. If she would lie, they implied, she, Maria, and the baby would be taken care of for the rest of their lives. It’s not clear if Maria Monk—she was known by her father’s last name—ever did spend time in a nunnery. But the bestselling book that would bear her name would prove to be one of the great literary frauds of the nineteenth century.

The Awful Disclosures of Maria Monk was the most-read book in America before Uncle Tom’s Cabin, selling a record 300,000 copies. First published in the States in January 1836—just a few months after Hoyt and his colleagues visited Mrs. Mills—the book recounts Maria’s time among Montreal’s Black Nuns at the Hotel Dieu Nunnery, first as a novice and then as an initiate. The book was ostensibly written by Maria herself, who is taught by a Protestant to read and write but sent to Catholic school to learn French. Some time later, having “attended several different schools for a short time,” Maria becomes “dissatisfied, having many and severe trials to endure at home.” She remembers her Catholic friends’ positive experiences with their religion, and she decides to become a nun. After she takes the veil, Maria alleges that, far from being a saintly community of celibates, the nuns were sexually abused by the city’s Catholic priests, a real-life tale seemingly ripped the pages of the Marquis de Sade. According to the book, the errant nuns became mothers, too—the babies they bore were baptized, smothered, and buried in a lime-layered pit in the basement of the nunnery.

For readers in 1836, Maria Monk was considered quite racy—one editor turned it down because he considered it too salacious to publish. But by modern standards, its sex scenes are coy. Even before Maria takes her vows, she has some sense that Catholic priests are not the pure and holy men they’re meant to be. A school friend tells her that, during confession, a priest conducted himself in a way “so criminal and shameful...I could hardly believe it,” Maria reports. And she herself finds herself in the confessional with priests who were “indecent in their questions and even in their conduct” and who made comments “of the most improper and even revolting nature, naming crimes both unthought of and inhuman.” Still, she doesn’t realize that the nuns are implicated in any of this until after she’s initiated. “One of my great duties was to obey the priests in all things,” she writes. “And this, I soon learned, to my utter astonishment and horror, was to live in the practice of criminal intercourse with them.”

The revelation of sexual abuse, along with the accusation of infanticide, comes early in the book. And while Maria reveals other campy but satisfying details later on—the priests have a secret signal, a “peculiar kind of hissing sound” they use to gain entry to the nunnery from the outside, a subterranean passage they can use if they’re willing to climb a few stairs)—the most detailed she gets about the actual rape is her description of her first night as a nun:

Father Dufrèsne called me out, saying he wished to speak with me. I feared what was his intention; but I dared not disobey. In a private apartment, he treated me in a brutal manner; and from two other priests, I afterward received similar usage that evening. Father Dufrèsne afterward appeared again; and I was compelled to remain in company with him until morning.

The shocking parts of Maria’s story are studded into a thorough attack on Catholicism: the Mother Superior is greedy about money, the priests disparage the Protestant Bible as a dangerous book, the nuns believe in ghosts. When Maria Monk was published, anti-Catholicism in America was on the rise. Irish immigrants had started to fill the cities of the Eastern seaboard; in 1834 a mob burned down a Catholic convent in Boston. Maria’s story was not the first account from an escaped nun, but it was the most successful. Her book was backed by a trio of Protestant leaders known to be campaigning against the influence of Catholicism in America: Theodore Dwight—supposedly related to Jonathan Edwards—and the reverends John Jay Slocum and George Bourne, all prominent nativist and abolitionist leaders. (Along with William Hoyt, they were same men who visited Maria’s mother.) They traveled with Maria from Montreal to promote the book in New York and other American cities, coached her, and, very likely, wrote her actual book. They also made significant amounts of money on it—and though Maria may have eked out a little profit, it was relatively small. She even tried, and failed, to sue them for her share.

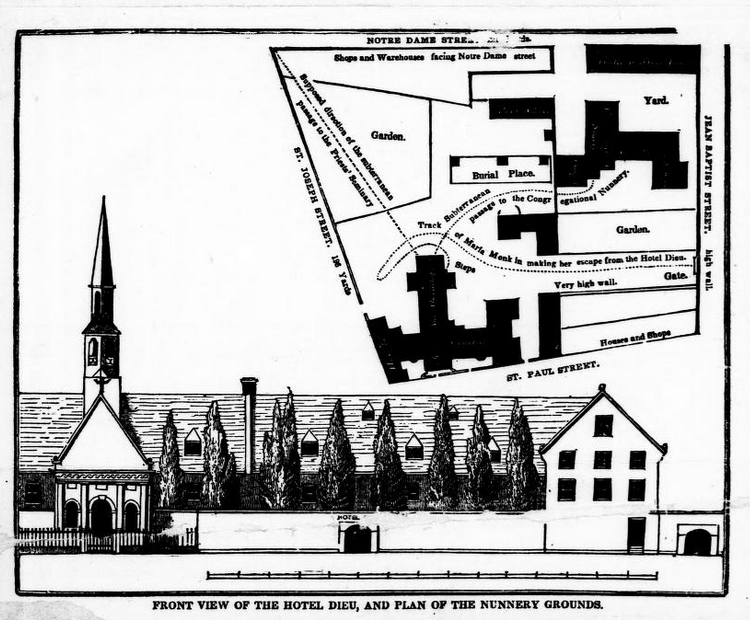

The subject matter drove readers to seek out the book, but after it became a bestseller the press began to tell a different story. In the book, Maria asserts her authority by describing the physical layout of the nunnery: it was impossible to verify, she writes, because no one’s allowed in the back rooms, but if anyone were to gain access, they would see exactly what she described. In 1836, the journalist William L. Stone visited the Hotel Dieu nunnery, was allowed access to the entire building, and found nothing at all resembling the place Maria Monk described.

Newspapers began to report that Maria was far from saintly, saying she had spent time in a Catholic halfway house for wayward women. She was described by Stone as decidedly un-nun-like; “pert, brazen, and rather pretty.” That was a relatively kind description; one broadside called her Hoyt’s “associate prostitute.” It’s unclear if this account of Maria’s life is any more true than the story published in The Awful Disclosures of Maria Monk, or how she met Hoyt and his Protestant fellows to begin with. Even her own mother’s account of her is suspect. Considering that Maria was one of the most infamous women in the country’s early history, it’s hard to see who she was at all.

Almost immediately after the book’s publication, though, the press began to excoriate her. Her mother’s account of Hoyt’s visit was one of the first counternarratives to appear “with brazen impudence,” Maria and her collaborators were “attempting to fix on the virtuous Catholic ladies and Catholic priests of Montreal, the shameless character which belongs only to themselves,” promised the introduction to a broadside containing Mrs. Mills’ account of Maria’s life story. But even after being accused of lying, Maria would still insist she had told Hoyt, Dwight and the other men her story as best she remembered it.

Maria’s mother would report to a Montreal justice in October 1835 that her daughter was prone to exaggeration. “My daughter was frequently deranged in her head,” Mrs. Mills said. “When at the age of about seven years, she broke a slate pencil in her ear...since that time her mental faculties were deranged, and by times much more than at other times.” When this story began circulating, a doctor in Philadelphia declared Maria unfit to take care of herself.

Maria describes her limited education at the beginning of the narrative, and it never quite makes sense that she could have written an entire book. And as critics started circling Maria and the men surrounding her, they admitted it was more of an “as told to”—she’d told them her story, and they’d helped her create a book (Theodore Dwight was likely the ghostwriter). Within a few years of publication, both the story and the men’s relationship with Maria began to break down. By 1837, Maria had split from the men she’d been traveling with—when Slocum tried to coax her back in Philadelphia, she tried to have him arrested. Once a chaste nun and bestselling author, Maria Monk was now considered by the press to be a mentally ill liar and prostitute.

It’s a sadly familiar tale: a woman comes forward with a terrible story, is embraced by the media, then is discredited and attacked as a sexually promiscuous liar. When Rolling Stone published the story of “Jackie” it followed a similar trajectory as Maria’s story, echoing an idea that had been gaining power: now, fraternities are bastions of rape culture; then, Catholicism is corrupt. Even after the Rolling Stone piece was investigated, Jackie was not entirely excoriated. Something traumatic happened to her, even if it was not exactly what she shared with a reporter. Was the same true of Maria?

Maybe Maria did have some cognitive disabilities, maybe she had, at some point, had sex for money or lived in a halfway house for sex workers. While relations between nuns and priests might have been as appropriate as advertised, how did they act toward powerless women like Maria? It’s not so hard to imagine a less-than-perfect priest trying to elicit stories of the “most improper and even revolting nature” during confession with a former prostitute. And no matter what, something did happen to her; she was taken advantage of. Whatever story she had, whatever bit of it might have been true, it was picked up by more powerful people who twisted it to their own ends. Maria didn’t profit from the book, or her infamy. She died poor and young—and, it seems, without anyone ever trying to reconstruct what had actually happened in her life. These days, we’re more willing to reevaluate the stories of women and sex, especially when they’ve been controlled by powerful men. It’s almost impossible to find any real interrogation of the men involved in Maria Monk’s story: How did they find her? Who gave them the idea to use her as the figurehead of an anti-Catholic book? Where did they go wrong?