Five years after the abolition of slavery and in the midst of a violent campaign to reimpose white supremacy fueled by the Ku Klux Klan across the ex-Confederate South, a Methodist minister in the remote mountain town of Waynesville, North Carolina, carried out an act of reparation apparently unprecedented in U.S. history. Asa Fitzgerald signed an extraordinary land deed in August 1870, conveying most of his remaining property to nine “colored persons” he and his wife’s relations had formerly enslaved. He transferred the land explicitly as restitution for the many years of unpaid labor “performed by them and their ancestors while in slavery.”

“Believing it to be the will of God,” Fitzgerald made his deed function as a kind of back payment, to restore “the proceeds of their labor which has come into our hands and pay them what is right and just for the labor performed by them for us.” The document estimated that the proceeds of their labor over time benefited his family by the sum of $3,400—a small fortune in that time and place—and declared publicly, for all to see, that this was a personal act of reparation.

After the Civil War, some former slaveholders did sell or gift land to people who had once been in their possession. Sometimes the recipients were their own biological children. In other cases, former slaveholders arranged land transfers to freedmen to maintain labor peace. Whatever the reason, these cases were not only rare but distinct in purpose from Asa’s radical action. Fitzgerald’s transaction was unique in its appeal to reparations. He carefully avoided the language of paternalism, justifying the deed not as a bonus for “faithful” or “meritorious” “service”—none of these terms appears anywhere in the document—but rather as a morally necessary restoration of the income and accumulated wealth that he and his wife had unjustly taken from them. The $3,400 figure he came up with was more than enough to warrant the transfer of about 330 acres of land. To the eldest of the nine, he even gave possession of part of his family’s own house.

For eight years Fitzgerald and his family lived with this remarkable arrangement in apparent peace. The Fitzgerald patriarch died in 1878 with little remaining property aside from his house, a small plot of land, and his library. It did not take long for his wife and children to take legal action undoing his novel transaction. They sued the nine owners and their spouses on the grounds that Fitzgerald had been suffering from “religious delusion” when he drew up the deed. This lawsuit, Fitzgerald v. Allman, set off a three-year legal battle that ended in a total victory for Fitzgerald’s widow and children. The case went all the way to the North Carolina Supreme Court and injured a much larger population than the nine people forced to relinquish the land they had earned; it also did significant collateral damage to civil rights protections in the state. The local court’s decree charged the black landowners with the costs of the suit, a sum high enough to strip them of the little wealth they had acquired. The end result of the minister’s reparation deed may well have left them more impoverished than they had been before their temporary ownership of the land.

This disastrous outcome appears to be inconsistent with a more positive trend documented in Melissa Milewski’s book Litigating Across the Color Line: Civil Cases Between Black and White Southerners from the End of Slavery to Civil Rights. Her study shows that after emancipation black litigants in the South had a surprisingly high success rate against white litigants in civil cases, especially over property. Milewski does make this important caveat, however: “In cases that had real potential to affect southern society, black southerners struggled to have their cases heard…or habitually ended up on the losing side.” And the Fitzgerald case opened up one of the most potentially explosive issues of all: the question of reparations.

Asa Fitzgerald, raised in the isolated mountains of western North Carolina, was exceptionally educated for his time and place. His father, Samuel, was a prominent man in their small community who often served as a justice of the peace or presiding magistrate at the county court. Asa’s career was set early: in 1845, just after turning twenty-one and reaching legal adulthood, he became one of the few men formally admitted to practice law in Haywood County Superior Court. Four years later he married Julia Benners, who came from a wealthy slaveholding family in the marshes surrounding New Bern on Pamlico Sound in eastern North Carolina. The couple probably met through Julia’s sister, who had moved to the western mountains to settle with her new husband.

The Benners were a cosmopolitan, multilingual family, originally French Huguenots who had emigrated via Holland to the tiny Dutch island of Sint Eustatius in the Caribbean, where they seem to have made a fortune as international merchants. Julia’s father, part of the first generation to be born in North Carolina, was sent back to Amsterdam to be educated and to do the European grand tour. When he died in 1837 he left a considerable estate, including twenty-two enslaved people who were divided among his children over the next decade.

Asa became a slaveholder and a man of some wealth through his wife’s inherited property in human beings. With the business of slaveholding came the duties of managing his wife’s human property, responsibilities that did not mesh with his lifelong tendency toward strong moral convictions. A friend from boyhood testified in court that Asa—who embraced the temperance movement at the tender age of fifteen—had a good mind but was “rather sensitive—always secluded.” In the early 1850s, after the sudden deaths of his first two children and a younger brother, he seems to have had a nervous breakdown, or an “attack of nervous fever,” as Julia called it in her own court testimony years later. He “fell into melancholy, secluded himself, [and] read his Bible.” When Asa, a man who had never talked about religion before, started to emerge from his depression, he spoke of hearing a voice calling him to preach.

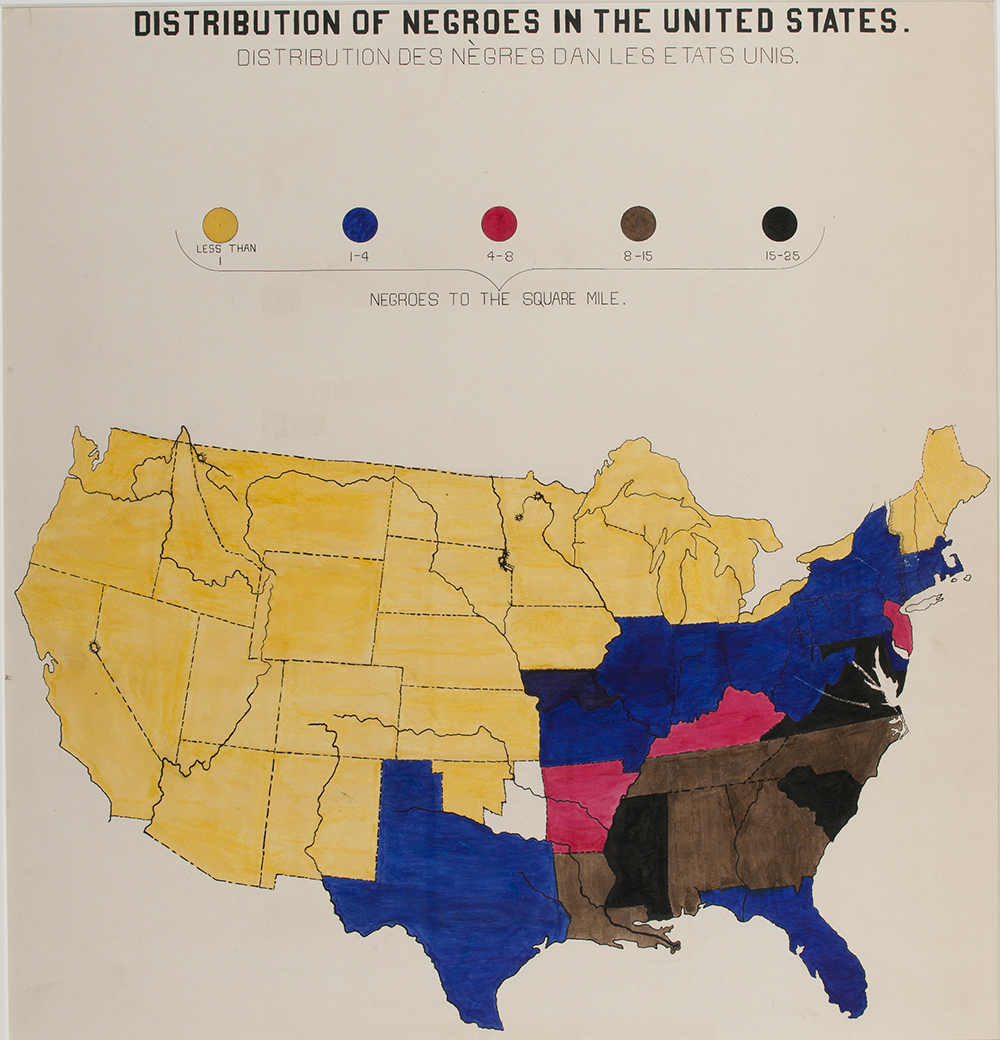

Fitzgerald’s thoughts turned to slavery: he let Julia know in confidence that he now thought it a sin to hold people in bondage. He was secretive about his convictions at first because even in the mountains, where the enslaved population was much smaller than in the lowlands of eastern North Carolina, this idea was scandalous. In Haywood County the enslaved population was less than 6 percent of the total, yet the institution was socially and economically intertwined with every aspect of community life. The local white elite to which Asa belonged embraced slavery wholeheartedly as a means of acquiring labor, capital, and status.

In 1856, after much hesitation and some false starts, Fitzgerald took a momentous step and “went north.” He entered the Methodist General Biblical Institute in Concord, New Hampshire, to study the Bible in Hebrew. No one from his region had ever done such a thing. Of the 424 men who attended the Concord school from 1847 to 1860, less than a dozen came from states that would join the Confederacy. When he returned home later that year, he came out openly as antislavery, determined to set the people in his possession free.

By the 1850s state laws in the South had been tightened to make it ever harder to free or “manumit” an enslaved person. Restricting the freedom of owners to do what they wanted with their property was an obvious contradiction in a system supposedly founded on property rights, but these restrictions were fueled by ever-growing fears that a free black population would encourage escape and even insurrection. North Carolina required owners to post a large bond for each freed person, and any freed person had to leave the state within ninety days of manumission. Large numbers of manumitted people ended up moving to the African colony of Liberia with the help of their former masters and the American Colonization Society. In 1858 Asa made this proposal to his own people. According to his wife, “He called the negroes in, told them we had concluded to free them. Said they must go to Liberia. He would give them $100. They would be sent free.”

They turned down the offer, telling Fitzgerald they would rather be sold to his wife’s family. Emigration to Liberia would have sent them to an unknown land and threatened the arrangement their kin group already had. At that time, Julia’s two siblings lived together in the same household on property adjacent to the Fitzgeralds’. By making a sale within the family, they could all stay together. Accordingly, Asa sold Julia’s enslaved people to her siblings, Joseph Benners and Sarah Norwood, except for one man named Isaac who chose the nearby Allman family, and would give his surname to the lawsuit as the lead defendant.

During and after the Civil War, Asa became increasingly absorbed in his religion, forgoing much of his legal work. His health, never robust, declined. His income dropped enough that his father brought over food and provisions to the family and began to take over business matters, such as paying the annual property tax. The house fell into disrepair; the roof leaked. This turn of events must have been particularly shocking to Julia and her own kin, who had grown up in splendid material circumstances and had every expectation that would continue.

Just as his income was bottoming out, Asa decided that he wanted to divest most of his property and distribute it to the poor and disadvantaged. This must have alarmed his wife and family even further, but he maintained that the Lord would provide for them if they did their religious duty. Meanwhile he taught his children at home, giving them all a general English education and training some of them in Latin. Despite his poor health, Asa began to assume the role of minister to the local black community, preaching at funerals and performing Sunday services. In that role, he stayed well-informed on the progress of Reconstruction.

By this time there was “great excitement on the negro question,” as one white witness said at the trial years later. The Ku Klux Klan had unleashed a reign of terror on black and white Republicans in western North Carolina in order to defeat the Reconstruction government elected in 1868. Open warfare sometimes broke out between the Klan and the Union Leagues that supported Reconstruction. This reality disturbed the peacefully inclined Asa so much that he published a letter deploring the violence in June 1870, only a few months before writing his reparations deed. The letter appeared in the Methodist Advocate, a newspaper started by the northern Methodist church for southern readers:

Is it not time, Mr. Editor, for all good citizens who desire and labor for the peace and good order of society, and especially for all true Christians and ministers of that Gospel which breathes peace and good will toward all mankind, to speak out?

The double use of the emphasized “all” was an unmistakable sign that he considered freed people to belong fully to a biracial civil and religious polity.

Asa became more insistent on divesting the family’s remaining property and using it to recompense the people they had once enslaved. According to his father, Asa asked him at one point to pay $3,000 to those formerly enslaved. When his father refused, he devised the reparation deed instead and pressured Julia for many months before she “was driven to sign the deed.”

The voices of the black kin network in this story went largely unrecorded. This is typical of the nineteenth century; African Americans in the South usually were banned from testifying in court and, until emancipation, barred from literacy as well. Isaac and the other defendants were nonliterate, but hardly any oral testimony of theirs survives either. Still, their complex lives can be suggested at least in part from other sources.

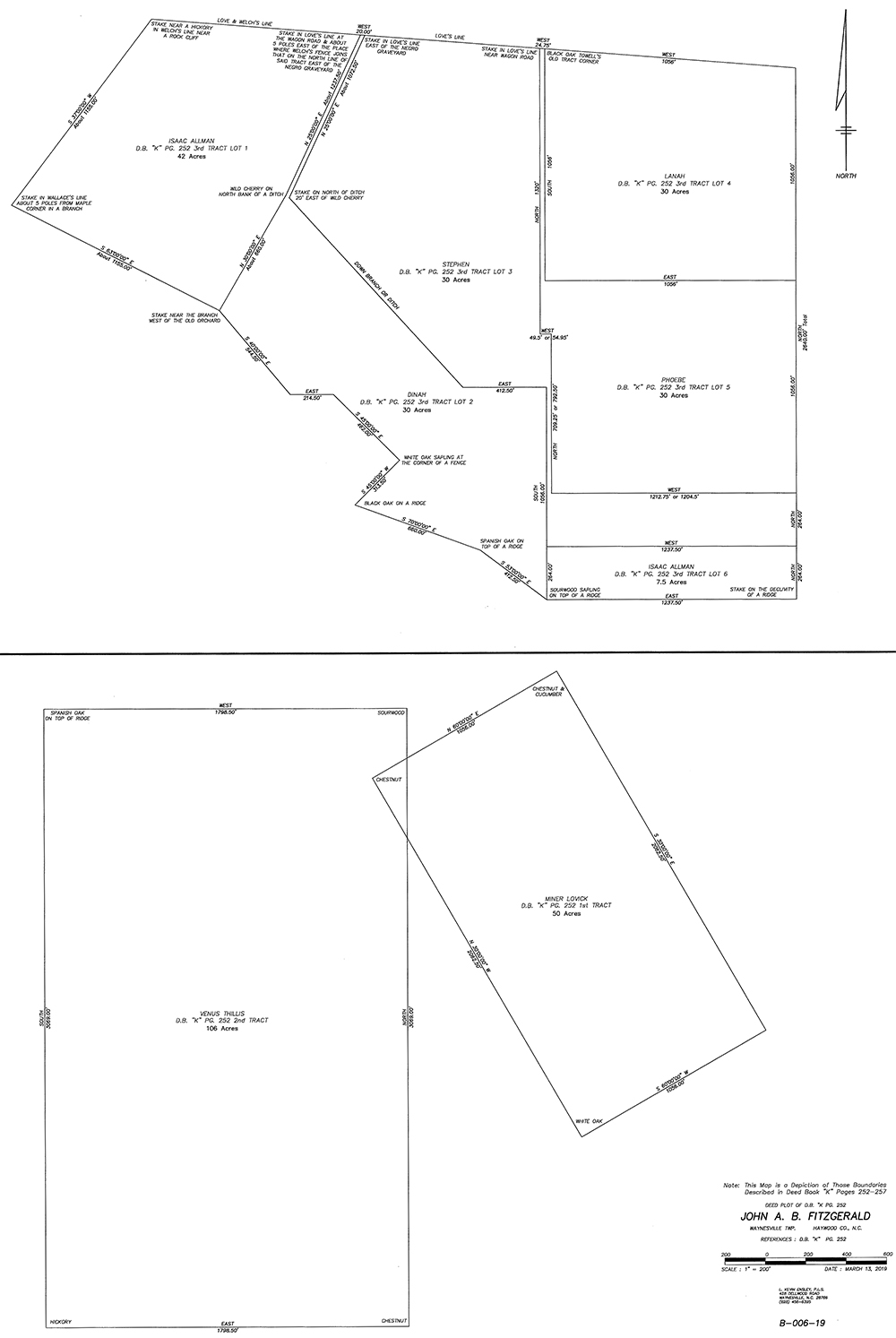

Asa identified the nine kinfolk in the deed as descendants of a woman named Venus. She first appears in the written record in the 1798 will of John Benners, Julia’s great-uncle, who bequeathed Venus to Julia’s grandfather and his siblings. Through them Venus came into the possession of Julia’s father Lucas Benners in New Bern. In Lucas Benners’ estate inventory of 1837, five people correspond to the first two generations named in Asa’s deed. They were Venus, age forty-three, and her children Jule, age twenty-five; Isaac, age eleven; Phillis, age nine; and Miner, age three. They would become Juliet Benners, Isaac Allman, Phillis Norwood, and Miner Lovick. (The Lovick surname comes from marriage partners to the Benners—John Benners married two Lovick sisters and probably obtained much of his enslaved property from them.)

When Lucas died they were hired out year by year to different households to generate income. The first ad in the local newspaper described them as “excellent field hands, consisting of men, women, and boys.” They were indeed skilled farmers, judging by the work they did after emancipation. After several years of rented labor, the family was divided among the various Benners heirs. Only the youngest of Venus’ children, Miner, stayed with her; the other three seem to have been distributed to three different Benners siblings. In 1848 twenty-year-old Phillis took an extraordinary risk and ran away. She was caught, spent seven days in the Craven County jail, and eventually returned to the Benners family.

By 1850 it appears that the entire group of five had been transplanted to western North Carolina to live with Julia; her brother, Joseph Benners; and her sister, Sarah Norwood, all of whom had recently moved to the mountains. Venus died sometime in the next few years, but her children and grandchildren probably all lived and worked together because their owners—the three Benners siblings—lived on adjoining properties in Waynesville. When Asa sold Phillis and her children to Julia’s brother and sister in 1858, no one had to move.1

In the years after the 1858 sale, Phillis’ family scattered within the local area and began to set up their own separate households. Isaac went to the Allman family nearby in Haywood; Juliet and Miner were probably hired out to others, Juliet perhaps with Asa’s father. Miner ended up in the neighboring county of Buncombe; he is listed there in the first post-emancipation census, taken in the summer of 1870. He appears there as a farmer, with a wife and four daughters under the age of five. Buncombe had a much larger black population than Haywood. Miner may have gotten his farm tenancy in Buncombe through his father-in-law, a relatively prosperous black farmer who lived nearby.

Isaac also seems to have met his wife and twelve-year-old stepson before or during the war. The wife and son match two enslaved people listed on the 1860 slave schedule in a household adjacent to the Allmans. The three of them then appear together as a family for the first time in the 1870 census for Waynesville, with Isaac identified as a farmer.

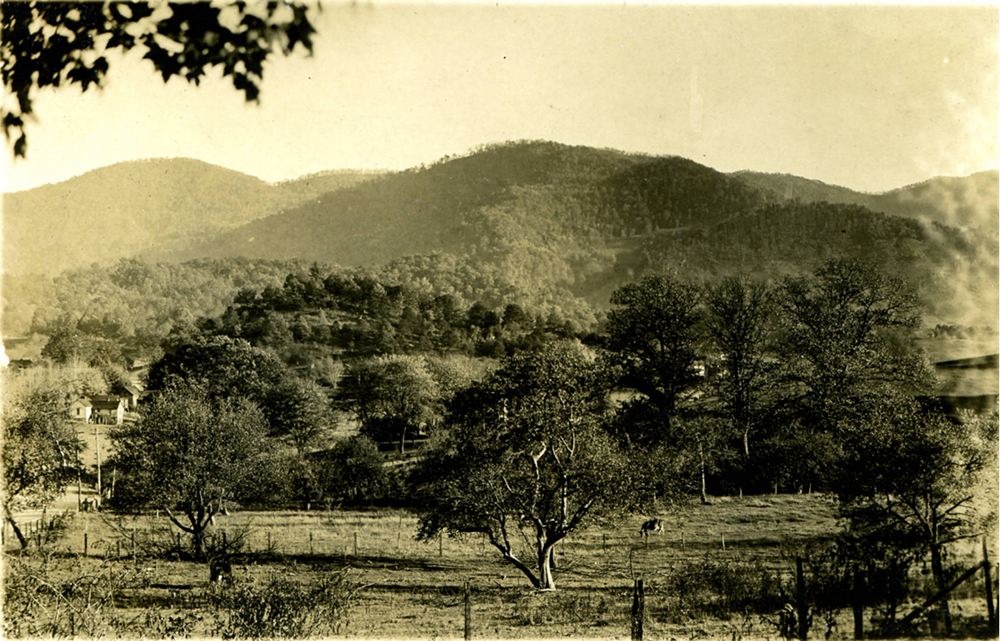

That summer of 1870, Isaac Allman and his newly legitimized family were living as tenants of Asa Fitzgerald. They were farming on a tract Asa called the “mountain lands,” a hundred acres of hilly land just south of the Fitzgerald farm. During the war he had acquired the land, through his father, from the widow of a Confederate soldier; shortly after the war he began settling freed people there. Along with Isaac’s family was another black family of seven people named Welch. Both families appeared on the agricultural census, which gives a picture of them as small agricultural producers with twelve to thirteen acres of farmland; some sheep and other livestock; and operations that produced corn, peas, potatoes, wool, butter, and honey. On this record they were indistinguishable from white farmers of modest means.

The arrangement of black tenants on a former slaveholder’s land was not exceptional in the aftermath of the war. But for Fitzgerald this was only a temporary expedient while he worked on persuading Julia to endorse the deed that would make his land transfer permanent. Under state law her consent to the transaction was needed. Shortly after she relented and signed the reparations deed, he also got her consent to sell a small piece of the “mountain lands” to the two orphans of the Confederate soldier William Swanger, who had once owned it. With these two deeds, he had in effect returned his land to its rightful owners.

Asa divided up the land very carefully to ensure that each lot contained productive agricultural land and distributed the lots according to the age and family situation of each, perhaps in consultation with them. Isaac and Miner each acquired fifty acres. Since both were already established farmers and married with children, they received more land than Phillis’ children, who were single and childless. Her children, with one exception, acquired thirty-acre lots.

Asa’s deed planned for the immediate needs of the older family members as well as the long-range future of the family across generations. To Phillis and her sister Juliet he gave “life estates,” meaning only for the duration of their lifetime. Phillis shared a lot with her twelve-year-old daughter, Lanah, who was to get full ownership on her mother’s death. Phillis also had the rights to ten bushels of corn per year from each of the lots belonging to her other children. Juliet’s life estate entitled her to a share of the Fitzgerald’s own house and a small plot of land nearby:

two rooms in the west end of the house where she now lives, the cellar under the house & the lot of land containing about 2 ½ acres above the spring & garden east of the house, during Juliet’s natural life, including the fence around the lot with right of way, water & fruit & wood for her own use.

After Juliet’s death, these two rooms, the cellar, and the small fenced lot would all revert back to the Fitzgerald family, thereby giving Asa’s heirs a very modest inheritance.

Asa drafted the deed with great skill to make his intentions clear and to withstand a legal challenge. The key passage reads:

To Isaac, Miner, Juliet & Phillis, children of Venus deceased; & Stephen, Venus, Phoebe, Dinah, & Lanah, children of said Phillis, colored persons and formerly slaves. Witnesseth that for and in consideration of services performed by them and their ancestors while in slavery, part of the proceeds of which (with labor performed for us amounting to three thousand four hundred dollars) has been inherited and received by the undersigned; and further in consideration of the sum of five dollars, the receipt whereof is hereby acknowledged; and believing that it is the will of God that we the parties of the first part [the Fitzgeralds] shall restore to the parties of the second part [Isaac et al.] the proceeds of their labor which has come into our hands and pay them what is right and just for the labor performed by them for us, the said John A.B. Fitzgerald & Julia his wife have bargained and sold…the following tracts or parcels of land.

It was written not as a deed of gift but as payment for services rendered. This payment was called the “consideration”: what the buyer brought to the table to compensate the owner for the value of the land. Asa’s deed specified a two-part consideration, the first being the $3,400 that he estimated they had contributed to his family’s wealth during their fifteen years of labor for them, and the second being a more nominal payment of $5, “the receipt whereof is hereby acknowledged.” Asa must have added the $5 stipulation to help distinguish the transfer from a deed of gift for which, typically, no money changed hands.2 But it was through Asa’s unprecedented formulation of the consideration for unpaid labor that the document became an act of reparation.

Legal precedent provided no clear road map. Asa was certainly familiar with land gifts made through the act of manumission, the legal practice of emancipating individuals within the system of slavery. Often done by a will and probate process, manumission sometimes included bequests of land or, in rare cases, gifts of land during the owner’s lifetime, to help give the newly freed their own independent means of subsistence. Since the owners were conveying gifts of freedom and land, they did not have to justify the transaction as a land sale based on a legitimate “consideration.” Moreover, the gift was almost never framed as an act of corrective justice. As a rule, manumission rewarded enslaved people considered “meritorious,” those who performed their “service” as they were supposed to in slavery—never those who resisted their bondage, refused to work, or tried to escape. This criterion of personal merit was often required by law, especially as most southern states tightened their manumission statutes in the nineteenth century.

One signal example that bent this tradition near to the breaking point was the will of Richard Randolph. In the document, drawn in Virginia in 1796, he explicitly declared his intention “to make retribution, as far as I am able, to an unfortunate race of bondsmen, over whom my ancestors have usurped and exercised the most lawless and monstrous tyranny.”

Randolph went beyond moral indignation and actually begged forgiveness from the enslaved people in his possession “for the manifold injuries I have too often inhumanely, unjustly, and mercilessly inflicted on them.” The document makes an unsparing critique not only of his own and his ancestors’ role in the system but of the system itself, “from the throned despot of a whole Nation to the not less infamous petty tormentors of single wretched slaves, whose torture constitutes his wealth and enjoyment.” Randolph was engaging in his own personal truth commission, acknowledging the crimes he and his nation had perpetrated on their victims—an expected step in most modern-day reparations schemes. The document goes on to

bequeath unto them the said slaves four hundred acres of my land, to be laid off as my wife shall direct, and to be given to the heads of families in proportion to the number of their children and the merits of the parties.

This was a relatively small portion of his estate, which included two thousand acres and a mansion, but enough to help establish a free black community that would endure into the twentieth century.

Randolph’s will was probably known in abolitionist circles but was not reproduced in print until 1876. (Ironically these manumission wills were first systematically collected and extracted in an early twentieth-century apologia for the Confederacy: Beverley Bland Munford’s Virginia’s Attitude Toward Slavery and Secession.) Even if Asa Fitzgerald had heard of this document, it would not have suited his purposes. The will made no attempt to calculate the proffered land as “consideration” for unpaid labor, and the language of merit crept back into the terms of the gift. Asa would scrupulously avoid this merit-based formulation in his own deed.

Typically, manumission and the occasional land gifts that accompanied it presupposed a horrendous moral balance sheet in which enslaved people typically started in debt to their owners. In this upside-down accounting scheme, enslaved laborers had to compensate their owners. The enslaved had to earn credits through their good, loyal service in order to balance the costs of food, clothing, and training provided by their masters. Manumission was not even a possibility until the enslaved person had made enough deposits of service to outweigh all the accrued debits on the balance sheet. When William Nodding petitioned the Tennessee state legislature in 1803 to exempt him from paying the onerous bond required to manumit an enslaved person, he wrote that his “conscientious Scruples” were about “the propriety of their being longer detained in Bondage than they compleatly recompence him for their bringing up.” Freedom was justified only if the accrued value of the person’s service adequately reimbursed the owner for all the “benefits” he provided—as in a contract for guardianship or apprenticeship.

Although Nodding maintained that his enslaved people “ought to have the same opportunity of doing well that any person becoming a citizen & free man of the State at that age or under would have,” yoking this antislavery conviction to a cost-benefit accounting scheme blunted its critical force and undermined its corrective potential. Proslavery advocates could use the same kind of accounting scheme to justify perpetual enslavement. They argued that no amount of slave labor would ever pay off the debt enslaved people owed to America for the cultural benefits they received—chief among them Christianity’s promise of redemption, which was quite literally priceless. This kind of accounting still echoes in some of the arguments made against reparations today.

Slavery crippled the imaginations even of its opponents as they tried to envision an interracial world without bondage; men such as Randolph and Nodding could hardly conceive of a state of affairs in which this institution would be brought to account for its massive theft of people’s labor, potential, and autonomy.

Asa did not say that the “former slaves” were meritorious or faithful or deserving of special treatment. He did not say that the land was necessary for their support; the year was 1870 and they had been managing on their own already for five years. Instead Asa framed the deed as an act of restorative justice. It is worth repeating the last sentence of his preamble in full:

We the parties of the first part to this indenture shall restore to the parties of the second part the proceeds of their labor which has come into our hands and pay them what is right and just for the labor performed by them for us.

There is a specific reason why he focused on the unjust appropriation of their labor rather than their autonomy or, most fundamentally, their humanity. He needed to come up with a dollar figure for the deed’s “consideration,” and the most straightforward way to do that was to measure the value of the labor he and his wife’s family had taken from them.

The question remains, though, whether the number he came up with—$3,400—was a gross or net sum, whether he attempted to account for the owners’ costs of food, clothing, shelter, and so on in an imaginary balance sheet. The language of credit and debit found in Nodding’s petition is strikingly absent here, no doubt because Fitzgerald wanted nothing to do with the moral deception that enslaved people received any sort of genuine compensation for their imprisonment. But his carefully worded phrase, “the proceeds of their labor which has come into our hands,” does suggest that he was not merely estimating the value of their labor—he was estimating what his family had gained from their labor and what the enslaved people had lost. This calculation may well have accounted for the workers’ subsistence, but only to demonstrate that the net benefit to Fitzgerald’s family—and the net loss to the enslaved—was hugely consequential. Read this way, the deed was a refutation of the myth that the moral balance sheet of slavery could ever be even.

One possible way of understanding the deed is through the legal concept of restitution for “unjust enrichment,” for which the courts had already established a small body of precedent in relation to slavery. The context for these cases was altogether different, however. They originated in suits brought by free people of color who had been held illegally as slaves and thereby forced to work without compensation. Instead of pursuing a remedy through a tort action, which alleged harm due to wrongful imprisonment and mistreatment, the plaintiffs in these cases took a legal path they thought more likely to get traction with white southern judges: suing to recover the value of their services. Most southern courts did recognize the legitimacy of these suits. Even so, judges carved out a “conventional exemption” for the slaveowners who had been caught holding free people illegally. Courts presupposed that slaveowners must have acted in good faith. How could they be expected to know for sure that the people in their possession were legally free? Judges bent over backward to take pity on the slaveholders and avert any possible loss they might face: “There ought to be some reasonable limit to a reclamation which might beggar a party, who, in good faith, had only spent and enjoyed what he believed to be his own.”

While the courts worried about beggaring slaveholders—even those who had been holding their slaves illegally—they showed little concern for the losses of those who had been wrongfully enslaved.

If Asa did study the legal doctrine of unjust enrichment, he took the concept and extended it much more radically to all labor performed under slavery whether legal or not. Asa framed the deed of land as restitution for a long-overdue debt. According to this logic, Asa and Julia owed Isaac, Miner, Juliet, and the Norwoods $3,400 for their years of labor under slavery. The Fitzgeralds traded them their land to pay back that debt. The practice of using land as barter for back debt happened all the time in the mountains of North Carolina, where cash was perennially scarce. Even though “consideration” was usually measured in dollars, buyers often paid the equivalent in livestock or corn or other goods; sometimes the buyer simply “lifted” the seller’s debt.

What made Asa’s trade so radical was the notion that the Fitzgeralds owed the people they had enslaved anything at all. If they owed money for labor performed under slavery, then so did the rest of the white elite in Haywood and all across the South. Taken as a precedent, the moral calculus of this deed would justify a massive transfer of wealth from white property owners to those who had suffered the economic injury of slavery. The reparation that Fitzgerald wrote into his deed posed an existential threat to white supremacy in the South. The white community and its supporting legal structures would respond to the threat by relegating the very idea of reparations to the realm of the irrational.

Asa Fitzgerald’s remarkable reparation deed left his own once wealthy white family with relatively little property of their own. With his subsequent sale of the ten-acre piece of “mountain lands” to the two Swanger orphans, the Fitzgerald family was left with essentially no land and only a portion of their own house; the remaining two rooms and a small garden lot would revert to them on Juliet’s death. Julia, Asa’s widow, would later say that the sale impoverished her family and led to the early deaths of some of her children “by suffering and exposure.” For the nine black kinfolk who acquired the land, the deed certainly gave them a measure of independence and some wealth of their own, but it remains difficult to determine just how much they benefited.

The Fitzgerald farm had been effectively dormant. The agricultural census taken in the summer of 1870 reported no crop production at all and a relatively small amount of butter, honey, and orchard fruit. After the deed took effect, the old Fitzgerald farm became a hub of people and activity.

Isaac Allman and his nephew Stephen, with their respective families, seem to have moved onto the three lots designated for them in the deed, part of the old Fitzgerald homestead. The other three lots in that boundary were apparently settled by three black tenant families all named Welch, the same surname as the family who had lived on the “mountain lands” with Isaac before the deed was signed. Together the five households included over thirty people, most of whom worked the farms. They must have built new houses for themselves and worked hard to return the land to cultivation. The agricultural census for 1880 shows Isaac with a farm operation slightly larger than he had in 1870 and a small farm for Stephen; the Welches do not appear.

Phillis, Dinah, Phoebe, and Lanah, who owned the three lots rented out to the Welches, all migrated to Buncombe County. Phoebe and Dinah married brothers named Lowery and lived on the elder brother’s farm in Leicester. Phillis lived with them and listed no occupation on the 1880 census. For reasons unknown, Lanah was living several miles away in Asheville, working as a cook with several other servants in a white farmer’s household. Miner moved back to Haywood from Buncombe County and established a small farm on the “mountain lands” tract deeded to him.

It is likely that at least some of the black families helped out the Fitzgeralds. The elderly Juliet lived in their house as a “domestic laborer,” according to the 1870 federal census. She might have helped cook and clean for the black families and kinfolk on the property, but it is also possible that she worked for Asa and Julia. The only direct evidence we have of lingering service is a remark made by Isaac Allman, recorded in a deposition of Asa’s father Samuel.

It is the only instance in which any of the black kinfolk are given voice in the documentary record. Isaac was probably allowed to speak only because the deposition took place outside the courtroom. In his remarks Samuel painted a picture of his son totally ignoring his domestic responsibilities. Isaac personally cross-examined Samuel and reminded him of the times that he and Asa had worked on the garden:

Isaac Allman: Do you not remember that I came over there two or three different times when you were there, and Massa Asa sent for me, and broke up the garden?

Samuel Fitzgerald: I remember one time, and then he done it with my mare and perhaps he may have done it oftener.

Here we get a glimpse into their world, one in which Asa retained the title “Massa” despite two decades of effort to free his slaves and make restitution to them. Massa sent for Isaac, a man with his own farm and family, and Isaac came over to help out. Bonds of obligation persisted, due in part, no doubt, to the deed Asa made. Moreover, it behooved Isaac and his kin to do what they could for Asa’s family, since local whites were already muttering about these black people building their homes near the Fitzgeralds and benefiting at the expense of Asa’s own children.

Surrounded by hostile whites, the black landowners faced a situation that was not just unpleasant, it was terrifying. Since 1868, when Republican Reconstruction got underway in North Carolina, blacks in Haywood and Buncombe had been whipped, beaten, stoned, and murdered by the Klan and other vigilante groups bent on reimposing “white man’s government.” For Isaac and the others on the old Fitzgerald land, it was smart to play the part of the faithful servant and do what they could to keep Asa’s family fed. But their efforts to help out did little to bolster their prospects. When Asa died on May 4, 1878, they learned almost immediately just how precarious their new lives really were.

Asa left no will. True to his notion of duty, he had settled all his debts. But his personal estate amounted to a measly $155, half of which came from his book collection. Julia and her children wasted no time initiating a lawsuit to recover their former land and dispossess the black property owners. Even though Julia had put her own signature to the deed and taken an oath that she was not coerced, she alleged that Asa had not been mentally competent when he wrote it and that no legal consideration for the lands had been given.

The Fitzgeralds’ legal argument was circular: the deed was void because Asa was insane; but Asa was insane because the deed itself was insane. Why would anyone do such a crazy thing if he hadn’t been crazy himself? In the court case that followed, the question of Asa’s sanity was inseparable from the reading of his reparation deed.

The Fitzgeralds didn’t just demand that the deed be rescinded and that they be returned possession of the land. They also wanted $1,000 in damages over and above the court costs. This last demand was particularly cruel and pointless; the formerly enslaved defendants were—like most subsistence farmers—basically penniless. Isaac Allman and Stephen Norwood still owed Asa money on promissory notes from the early 1870s, which were labeled “desperate” by the estate administrators, meaning they had little or no hope of ever being paid. Collectively, the defendants had to issue a statement to the court saying that they were “wholly and totally unable” to pay the required bond in case they lost the suit and were responsible for the court costs.

Before the case went to trial, the black defendants and their two white lawyers petitioned the local court to move the case from Haywood County to the federal circuit court. They based their petition on a federal statute proceeding from the federal Civil Rights Act of 1866, which declared that when a lawsuit was brought against anyone who could not enforce their “equal civil rights” within the state, then on petition of that defendant the suit could be removed to the circuit court for that federal district.

The Allman petition argued that the defendants could not enforce their rights

on account of the fact that the plaintiffs are white persons in whose favor there is a great partiality existing in this locality, and the defendants are persons of color against whom there is existing in this locality a great prejudice on account of their color.

The Superior Court judge Jesse F. Graves granted the petition and ordered all proceedings in Haywood County to cease and be removed to the federal court. As Justice Graves was certainly aware, riding across the state from one superior court jurisdiction to another, African Americans had few if any rights in local courts, even at the height of Reconstruction. Although no state law barred them from jury duty—as state law did in West Virginia, for example—the practical administration of justice in local counties effectively did. The judge was also following a precedent that the North Carolina Supreme Court had set in 1871, when it ruled in State v. Dunlap that the civil rights statute extended to “include cases where, by reason of prejudice in the community, a fair trial cannot be had in the state courts.”

The Fitzgeralds immediately appealed Graves’ ruling to the state supreme court, knowing that their chances of prevailing would drop enormously in federal court, where African Americans could testify in trials and participate on juries. The opinion of the state supreme court came swiftly and definitively in January 1880, reversing Dunlap and dramatically changing civil rights law in North Carolina.

The state court took its cue from several recent decisions by the U.S. Supreme Court—including two fresh rulings on the issue of jury trials—that severely delimited the scope of the 1866 civil rights statute. These rulings declared that evidence of prejudice or even discrimination at the local level was not enough to warrant removal to a federal court. According to the new reasoning, the civil rights statute imposed a further burden on the defendants: they had to show that state law itself discriminated against persons of color. In West Virginia, where state law barred nonwhites from jury service, removal to federal court was warranted, but in Virginia, where custom rather than law excluded blacks, the remedy was unjustified.

The North Carolina court echoed this reasoning and used it to reverse the past ten years of civil rights law. The justices who issued the opinion were well aware that local courts did not need a state law to bar persons of color from juries and even from testifying. White officials were in charge of local justice and could largely do as they pleased, especially since they had white communities and voters backing them. Structural racism easily defeated black civil rights even without laws explicitly denying those rights. Perversely, the very pervasiveness of this structural racism was one of the major reasons the U.S. Supreme Court decided to backtrack on enforcement of the civil rights statutes. Arguably almost any local suit against a person of color could be removed to federal court because racist justice prevailed so widely in the states. To close the floodgates, the court had to impose increasingly severe limitations on the scope and potential impact of civil rights statutes.

North Carolina’s court ordered the Fitzgerald’s lawsuit to proceed in local court and charged the court costs of the appeal to the black defendants. That cost of $10.60 was by no means an insignificant sum for them. As disastrous as it was, the North Carolina decision did leave open one traditional remedy for the defendants: asking for a change of venue to an adjacent county based on local prejudice in the home county. These prejudice petitions typically rested on personal rather than racial factors, for example if the other party in the suit was a prominent local citizen against whom a jury would be reluctant to rule.

Isaac Allman petitioned for a change of venue early in 1881 and deployed a combination of reasons, personal and racial, that went far beyond the earlier petition. Through his lawyer he explained that the plaintiffs were not only white but almost all children—even more likely to elicit the jury’s sympathy. Before emancipation the white orphans of a man like Fitzgerald would have expected to inherit his enslaved people as well as his land, but now both were gone. Allman also pointed out that “there are no men of color on the regular jury or ever have been.” Whatever state law might or might not dictate, this was ironclad practice in Haywood County. Whites, Allman added, were by far the majority in the county, and the relatives of the plaintiffs were “men of great influence in Haywood County.” Julia’s brother, Joseph, for example, had become treasurer of Haywood County in the early 1870s and remained in office during the lawsuits. “On account of the color and poverty of the defendants,” Allman said, “there was strong prejudice against them for holding their land “against the orphan children of their master.”

Finally, Allman said, the plaintiffs were not just passively benefiting from this racial prejudice but were inflaming it. Their relatives and friends had “been active in denouncing the defendants.” When Allman was on the courthouse grounds during court sessions, he had heard white men who were likely to be on the jury denouncing him, the other defendants, and their attorneys.

There is no record of the Fitzgeralds disputing any of this. The case was promptly removed to Jackson County, on the west side of Haywood. While the change of venue may have helped to weaken the social networks that favored the plaintiffs, it did little to alter the racial dynamics. Haywood County in 1880 was 95 percent white and 5 percent “colored”; Jackson was 90 percent white, 5 percent colored, and 5 percent Cherokee. The jury for the case was all white, and there was no reason to believe that blacks had ever served on juries in Jackson County.

The politics in Jackson were actually much worse than in Haywood. Whereas Haywood in 1868 had been evenly divided between pro-Reconstruction Republicans and anti-Reconstruction Conservatives, Jackson had voted over two to one against the Republicans, the most lopsided tally of all counties in western North Carolina. The defendants would have done better to remove the case east to Buncombe, with its larger population of African American and white Republicans. We don’t know why the court shifted the case to more hostile territory, but it is hard not to think it was intentional.

The case finally came to trial in 1881. No transcript survives. Aside from the one deposition made by Asa’s father, we have no direct testimony at all. What we do have is comparable testimony from a subsequent trial record that does survive, Fitzgerald v. Shelton, the lawsuit later brought by the Fitzgeralds to recover the mountain land Asa had returned to the Swanger orphans. The Shelton suit, like Allman, rested on a charge of insanity. And since the only convincing case the Fitzgeralds could put forward for Asa’s insanity in the second case was the craziness of the Allman deed in the first case, the Allman suit was effectively litigated all over again in Shelton.3

The Fitzgeralds never suggested that Allman or his kin tried to influence Asa. The case rested entirely on Asa’s internal and unknowable mental state. The plaintiffs’ argument started with a major roadblock: the deed itself was evidence of its maker’s mental competence. It was a highly complex instrument perfectly executed with an unshakable internal logic. The family had also never initiated lunacy proceedings against Asa during his lifetime, even though he had begun to divest their property in 1858, twenty years before his death. The only indication in public that such a move might one day be coming was a strange notation in the 1860 census: the column listing Asa’s occupation read “parshally deranged.” By 1870 the census entry was back to normal and listed him as a “Methodist minister.” Since Asa’s intellectual skills—both lawyering and preaching—were obviously still intact, Julia and her family must have realized that he could easily defeat a lunacy charge.

Asa did not rave incoherently or lose inhibition control or see things that weren’t there. The case for discrediting his sanity would have to focus on social nonconformity: his withdrawal from white society coupled with the strangeness of his views and his act.

The Fitzgeralds had labels for Asa’s condition. The testifying doctor called it religious delusion; their lawyers called it “monomania.” Delusion and monomania were familiar terms in medical jurisprudence of the era, typically used in cases involving contested wills. Whereas common law had traditionally required a finding of total insanity to overthrow a will, the new legal argument posited a more limited form of insanity in which people could be “rational on all subjects except one”—the major exceptions to rationality typically being religion, politics, and sex. Nonconforming religious views could be diagnosed as monomania; so could abolitionism.

In nineteenth-century insane asylums, “religious excitement” was a common cause for admission, a strange state of affairs in a society that was deeply and almost universally religious. The case for religious delusion or excitement was not straightforward in Asa’s case. He did not have visions. He did not hear voices—except, his wife said, an inner voice calling him to preach. Asa had convictions, which were strongly opposed to those in his social and family circle. Radical conviction is often shocking. While it could be seen as a courageous stand against injustice, it could also be dismissed as a serious mental aberration. This becomes painfully clear in the testimony of his brother-in-law James R. Long, who was also a Methodist minister:

I observed from conversation with him that he had some strange views as to religious duty. I was not forcibly struck with any great peculiarities until 1869 or 1870. He believed if he did his duty God would take care of him and his family & that if he gave away his property in a sense of duty, God would provide. I told him on one occasion that persons thought him deranged and I think so too. I said they say you act strangely in deeding your land to your former slaves. He lingered and said they do not understand it. He said it was his duty to give his former slaves homes. I said what are [their] children to your own children. He said if I do my duty God will take care of them.

Asa’s “strange views” made him act “strangely,” especially in regard to slavery. The word strange, from its root meaning as foreign or outside, meant unfamiliar, abnormal, difficult to understand. In all these senses Asa’s deed was strange; no one in his old social circle had seen anything like it or knew what to make of it. Yet Long and the rest of the family knew that strangeness alone was not enough to make the case. The clincher they offered was that Asa had sacrificed the well-being of his own family for this strange notion of religious duty to his former slaves.

The family’s narrative was that Asa retired from the world, stopped making or even caring about money, and simply trusted God to provide for them somehow. He became more interested in the welfare of the black community than of his immediate family.

The most damning testimony against him, repeated by witness after witness, was that Asa had abdicated his responsibility to his family by pretending that “the Lord would provide” if he just did his religious duty. Yet the belief that “the Lord would provide” was commonplace in Methodism, amply supported by holy scripture. The great Reverend Francis Asbury himself sometimes went penniless and said, “I found by experience that the Lord will provide for those who trust him.” With authorities like this in agreement, was it even possible to draw the line between piety and monomania? Was it delusion to believe in Proverbs 10:3 (“The Lord does not let the righteous go hungry, but he thwarts the craving of the wicked”)? Or to follow the teaching of Matthew 6:25–27:

Therefore I tell you, do not be anxious about your life, what you will eat or what you will drink, nor about your body, what you will put on. Is not life more than food, and the body more than clothing? Look at the birds of the air: they neither sow nor reap nor gather into barns, and yet your heavenly Father feeds them. Are you not of more value than they?

Of course not everyone reading Matthew 6:27 could stop reaping and gathering; society would starve and collapse. Nevertheless, people doing exceptional service, like Asbury, could trust the Lord to provide and in return even got statues put up to celebrate them. In Asa’s mind, he was dedicating himself to that kind of service for God. How could lawyering or farming compare to the great religious work of atoning for the sin of slavery and making restitution to those who had suffered from it?

Julia Fitzgerald gave the most detailed and comprehensive account of Asa’s inner life and struggles, though it must be approached with caution. However self-interested her testimony may have been, it certainly makes clear that Asa struggled off and on with depression. After his breakdown and religious awakening in the mid-1850s, he did seem to be profoundly uncertain about his future direction. At one point he talked about going to China; it took him years just to get to New Hampshire. But step by step he focused increasingly on restitution for slavery and dedicating his ministry to the black community of Waynesville.

Julia fought him every step of the way and bitterly accused him of coercing her into signing the deed. He tried for months to convince her by reading aloud such authorities as Francis Wayland and William Paley, two famous midcentury theologians.4 He eventually threatened her, she claimed, telling her “he would never do anything for me and [the] children” until she signed. Finally the children begged her to sign, she said, and she agreed. We don’t know if she invented or exaggerated this accusation. The one child of theirs who testified did not speak to it, and later named one of his own sons after his father. But even if the charge were entirely true, it demonstrated that he was a cruel husband, not necessarily an insane one. As the North Carolina Supreme Court wrote in its later ruling on Shelton, “merely immoral, vicious and criminal acts would not of themselves be evidence of insanity.” If anything, Asa’s alleged campaign of coercion showed a cunning mind at work, not a disordered one.

Nevertheless, Julia tried to hammer her point home by blaming his failure to provide for them for the later deaths of three of her children. This last accusation was the most incendiary of all, but it was much less plausible given that three other children died young while the family was still comfortably affluent. As one doctor testified, the entire family had always been “delicate.” While Asa’s father said that he kept the family stocked with provisions, and Isaac reminded him that Asa had helped with the garden, we will never know the true extent of the family’s privations.

No testimony whatsoever is recorded on the key legal issue at the heart of the case: the deed’s unique formulation of the “consideration.” Witnesses simply repeated the point that Asa “gave away” his land, as if it were a deed of gift. Although the deed itself was adamant that it was not a gift, the silence on this point leaves the impression that the whole business of putting a value on labor performed under slavery and then trading land for that labor was too absurd to be countenanced. As Asa had told his brother-in-law, white people “do not understand it.”

For the most part the court record dismissed Asa’s own motivations and hopes in writing the deed and focused instead on the issue of his sanity. The only exception came in testimony from Asa’s near neighbor, a man named Albert Plott, who often visited and talked with him late into the night. Plott’s remarks give us a unique glimpse into Asa’s thinking:

I thought him sane, seemed to be intelligent and well informed. Talked on religion—was a warm Methodist, understood the Bible, understood doctrine of his church. He was an abolitionist. Had been north, sold off all his property. Had given his land to his black ones. Said it would be better for his children as it would satisfy the people he was going among.

Plott creates the impression of a man who had completely reorganized his life around the people he had once oppressed. This was his new community, the people he was now “going among.” His act of reparation would “satisfy” the community and cement his own children’s place in it.

As far as the law was concerned, however, Asa’s motivations, his impulse toward reparation, was beside the point. Slavery was legal until 1865, and Asa owed nothing to those he had held and worked under its legal structure. Even if one accepted the moral proposition that slavery was wrong and slaveowners were unjustly enriched, from a legal standpoint Asa’s conveyance of the land was a purely voluntary act. Asa Fitzgerald chose restitution. The law did not.

In March 1881 the full weight of the local and state apparatus of justice came crashing down on Isaac Allman and his codefendants. The all-white jury that tried the case ruled in favor of the Fitzgeralds on every point.

As an episode in legal history, the outcome shows just how thoroughly the supposedly sacred right of property could be vacated if the exercise of property rights threatened the ruling structure of white supremacy. In this respect Fitzgerald v. Allman belonged to the earlier legal tradition of restricting slaveowners’ rights to free their enslaved people—the ultimate hypocrisy given that the entire edifice of slavery was built on property rights.

But the outcome violated the property rights of the black kinfolk who held legal title to the land in an even more shocking fashion. The decree was an astonishingly punitive act against a group who had done nothing wrong. It was one thing to eject a squatter from someone else’s land, as the court often did; it was quite another thing to turn the full force of the law against people who had held sole undisputed title for eight years and made life plans accordingly. The defendants were never warned, as far as we know, that there might be a future cloud over their title. To the contrary, the deed was signed in black and white by Julia Fitzgerald, the very person who turned around eight years later and claimed the deed was invalid. How were these landowners supposed to anticipate her about-face? They had simply agreed to the transaction, as she had, and taken their lawful title with no reason to believe it was invalid. For ten years they and their tenants had held up their part of the bargain and lived as productive citizens, building houses, clearing fields, planting crops. Their improvements increased the value of the land, probably substantially. All this was taken from them without any compensation. Instead of being paid for losses that were no fault of their own, they were punished: the jury ordered them to bear the legal costs of their own dispossession. Unlike the slaveowners who had been so well protected by southern courts, these black landowners had no court working to prevent them from becoming “beggared,” even though “in good faith, [they] had only spent and enjoyed what [they] believed to be [their] own.” Once again, as in slavery, the fruits of their labor were stolen from them. They now deserved a double dose of reparations.

There can be little doubt that the lawsuit had a devastating impact. In a single stroke the defendants lost virtually all their wealth and got saddled with a major new debt. They had to leave their homes and resettle elsewhere. The future earnings they expected from the farms they had improved and cultivated were gone. Their children’s inheritance vanished.

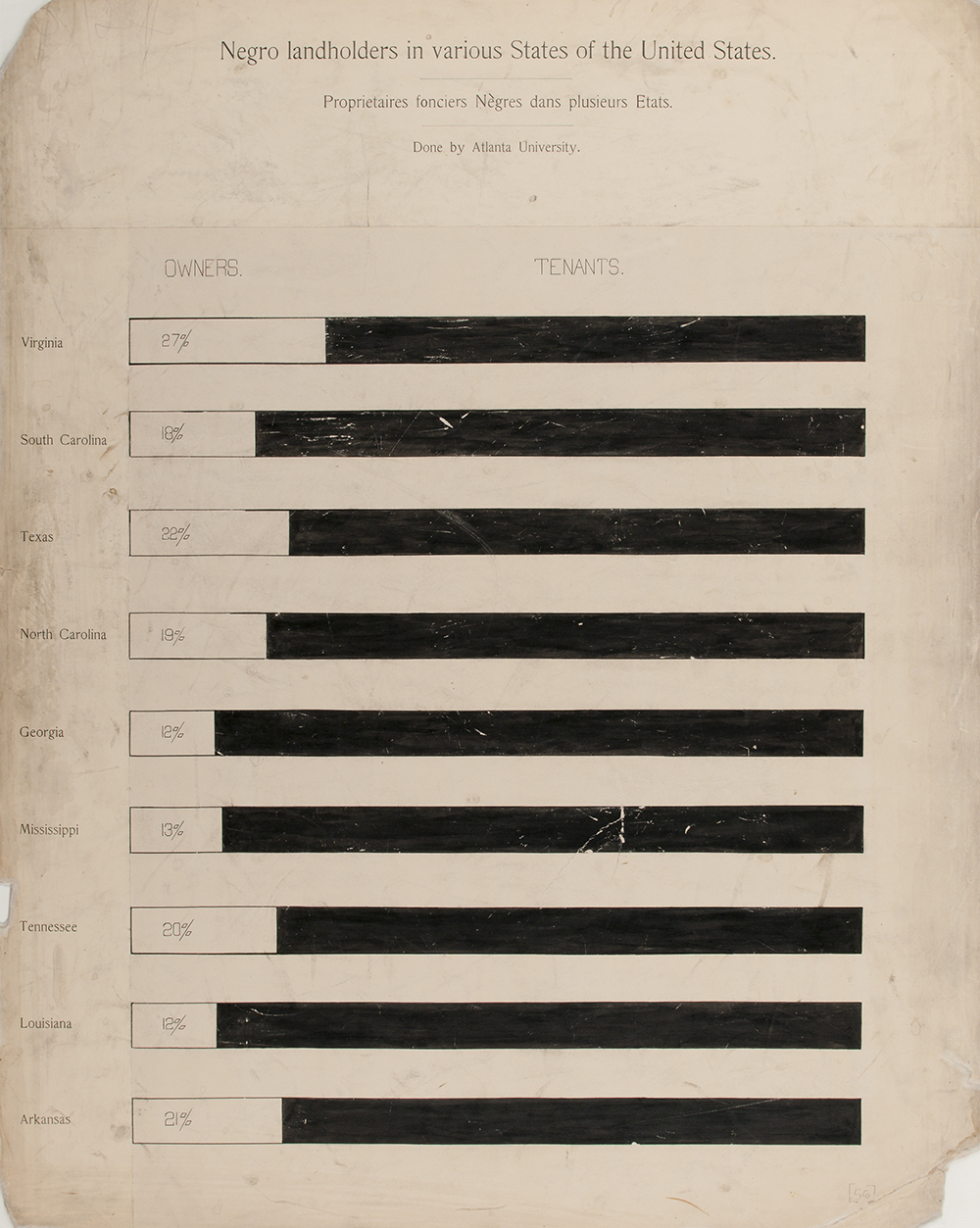

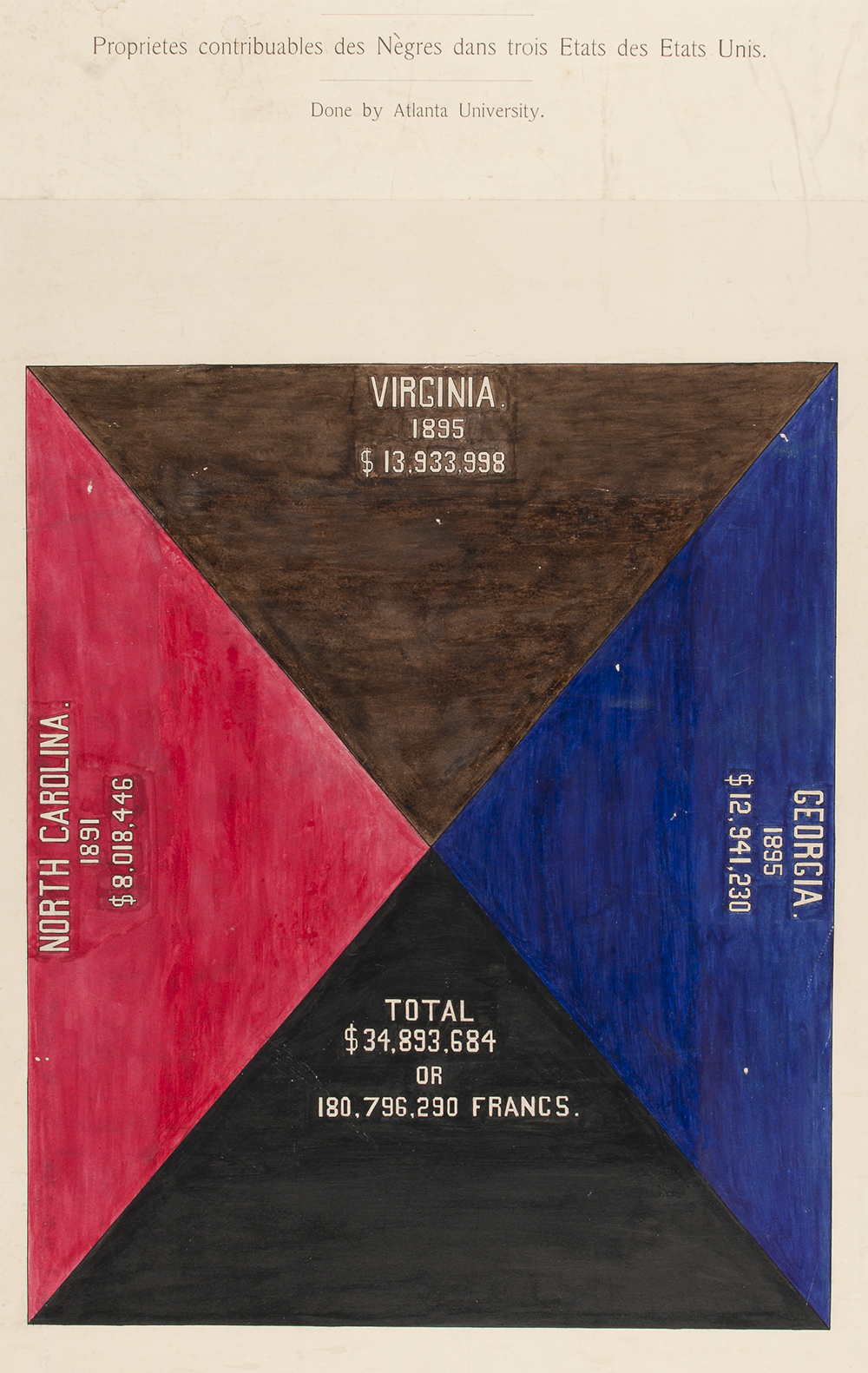

The results can be traced in their census listings. Only one of the nine retained land ownership: Phillis’ daughter Phoebe, who had married a Lowery. While they managed to hold on to their farm in Buncombe County, the land had come through her husband’s side, not her own. Even so, as her husband declined in old age she had to work as a washerwoman in a private home to supplement the family earnings. Daughter Dinah, who also married a Lowery, became a widow and a renter, working as a laundress, while her grown children living with her also took laborer or servant jobs. Leading defendant Isaac Allman became a farm laborer and renter into his old age. Phillis’ son, Stephen, followed the exact same trajectory, while the rest of the heirs disappeared from the census altogether. The one exception to this pattern was Stephen’s widow, Callie Smith, who somehow rebounded from her husband’s misfortunes and death and managed to buy a home for herself in the black section of Waynesville, where some of her adult children also appeared on the census.

In the meantime the Fitzgerald family worked aggressively to consolidate its control of Asa’s former landholdings. Before the ink was barely dry on the decree against Allman et al., the Fitzgeralds filed suit against Shelton, their white neighbor who had been renting the Swanger lands since 1879. That litigation dragged on for six years, producing yet another state supreme court ruling and two more trials. Once again the family prevailed decisively.

That verdict was also egregiously unjust. The Swanger orphans, by now adults living in Tennessee, were the owners of record, holding a deed of sale that had been signed by the plaintiff Julia Fitzgerald and duly registered in Haywood County. Yet they were not even served notice of the legal action against their tenant, much less made legal parties to the action. Shelton was left to fight the suit on his own, and he found himself having to litigate an insanity case based not on the facts in his case but on the earlier reparation deed to Allman et al. The trial court would not even allow him to enter into evidence a letter written by Asa Fitzgerald explaining the rationale for his deed to the Swanger children. Shelton appealed that ruling, and it was reversed by the North Carolina Supreme Court. In a highly sensible opinion, Justice Augustus Merrimon held that juries should consider a variety of evidence relating to “the transactions, declarations, and conduct of the party whose sanity is in question.” He added:

It is not every act that seems to be thus [absurd, unreasonable, and unnatural] that is so in fact; it frequently turns out that what so appears is just the reverse, and tends to prove the intelligence and wisdom of the person doing the act in question.

But even after a new jury trial was held, when forced to consider the evidence of Asa’s letter, the jury came to the same verdict of insanity. Apparently the reparation deed was so abhorrent to white juries that it outweighed the considerable evidence of sanity that Shelton was able to muster with his own witnesses and the facts surrounding the Swanger deed.

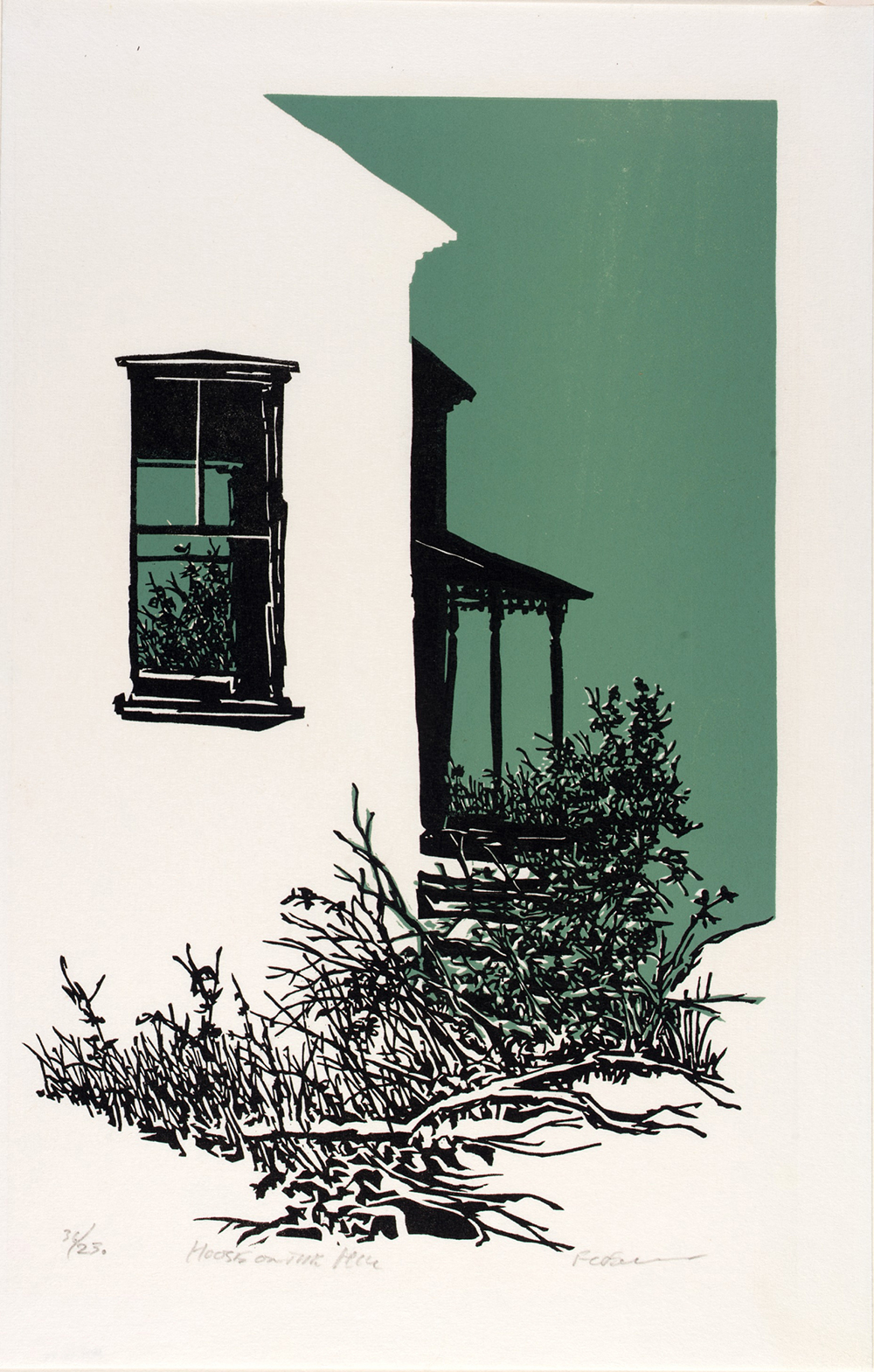

The impact on Shelton, however, was much different from what it had been on Allman and his kinfolk. Shelton only had to pay $5 in damages for each year he rented the land (plus the court costs), which meant that he probably came out slightly ahead on the tenancy in the end. He still had his own farm near the Fitzgeralds. Today his lovely two-story house on the property is preserved as Shelton House and the Museum of North Carolina Handicrafts. In stark contrast to the black farmers who once owned the land nearby, Shelton had his name immortalized in the local landscape. Shelton’s whiteness—with the accompanying social, financial, and judicial assets—cushioned his loss and enabled him to rebound fully.

After winning the Shelton suit, Julia Fitzgerald went back into court yet again to claim a “widow’s dower” in the lands her family had successfully repossessed. More legal actions unfolded before the lands were finally partitioned among the various Fitzgerald heirs. At that point it is hard to imagine that any of the black kinfolk were still on the property even as tenants. Julia and Asa’s oldest surviving son, Joshua, in a curious twist of fate, married a Swanger, first cousin of the orphans who had lost their land to him and his siblings. Joshua’s children and their cousins sold off some of the land in the mid-twentieth century, but family descendants still retain ownership of some of it. Their family name survives in a tiny street, Fitzgerald Lane, about a half mile down the road leading from Shelton House.

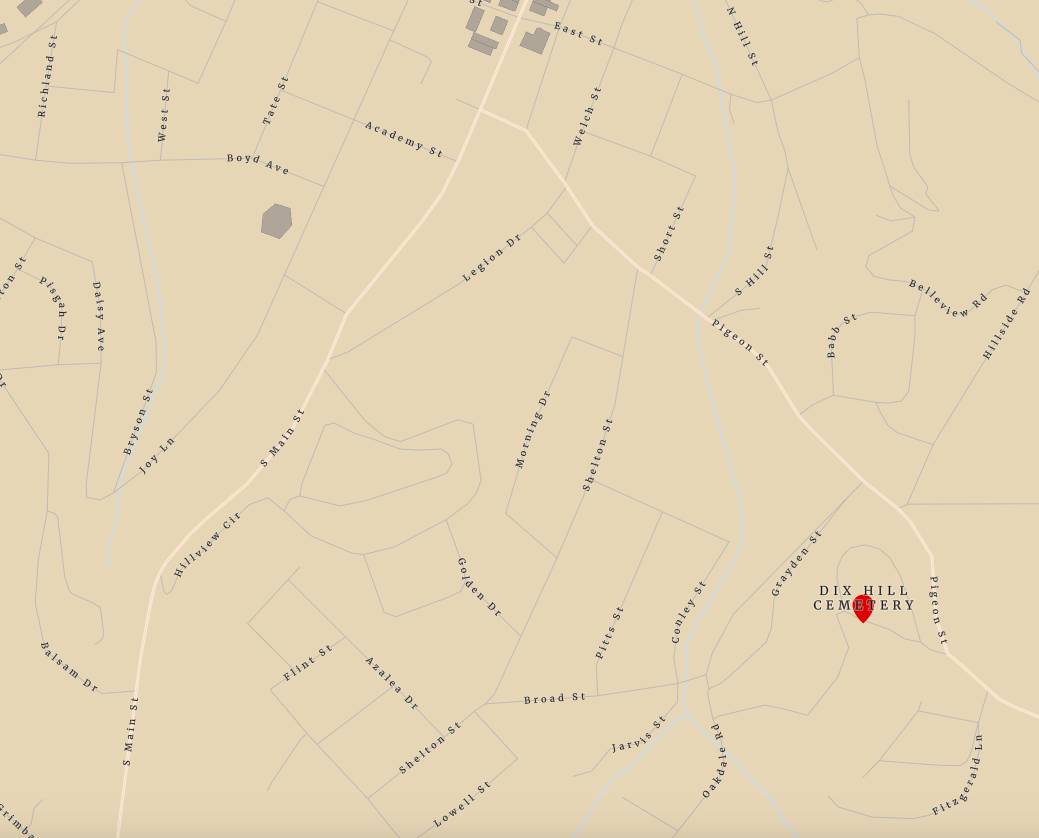

What is far more surprising is that the same road, Pigeon Street, became the center of the local black community beginning in the late nineteenth century. Under Jim Crow, the segregated community had its churches, school, cemetery, and many of its residents along Pigeon Street in close proximity to the Fitzgerald family land. This “colored” or “negro town” may owe its origins, at least in part, to the small community that once occupied Asa Fitzgerald’s old land. For example, the black cemetery, which still survives today, is located a short walk from Fitzgerald Lane. Callie Smith, Stephen Norwood’s widow, bought a home on Pigeon Street and lived there for decades, probably less than a mile from where she and her husband had owned their farm and had their first three children.

Looming over this whole sad episode in the history of reparations is the question of who was in their right mind.

We do not have to deny the reality of mental illness to accept that what constitutes insanity shifts over time in response to social changes. Epilepsy, alcoholism, masturbation, and “disordered menstruation” are just a few of the phenomena that were treated in insane asylums in Asa Fitzgerald’s day. In some societies, “cognitive disabilities” could be seen as psychic or spiritual gifts. Religious faith has never escaped these conflicts. What nineteenth-century lawyers or doctors called religious “delusion” or “monomania” was the very behavior that once made people saints or prophets.

By the time Asa wrote his deed, there was already substantial legal debate over the validity of these diagnoses of partial insanity. Columbia law professor John Ordronaux, writing in 1868 about religious delusion, asked, “Shall every Millerite and Mormon be deemed incompetent to make a will or a contract, though in other matters sane enough?” He made a sweeping case against monomania:

It is this extreme difficulty of determining what amount of individual dissimilarity any person shall be allowed to exhibit in his opinions and conduct, as against a certain arbitrary and conventional standard…which renders the doctrine of monomania so illogical. For, in its strictest application, it is sufficient for anyone to be unfashionable in garb, demeanor, or opinions to be at once decreed insane; and the only standard of mental health recognized therefore would be one never originally created, viz.: entire uniformity in all things between men.

Ordronaux put his finger on the essential issue: nonconformity. It is hard to disentangle issues of mental health from social definitions of conformity and the policing of deviance. Societies have always had to face the question whether any departure from social norms threatens the existing social order or can safely be absorbed into that order. The history of insanity, therefore, is a history of power. The social “deviance” of Asa Fitzgerald was alarming to his white community because it threatened the white supremacist order on which their own power rested.

Ultimately, then, we cannot pry apart the question of Asa Fitzgerald’s right mind from the question of society’s right mind. How we understand and diagnose the white supremacist society in which he lived is key to how we diagnose the man and his deed. Asa’s behavior may well have been hurtful or even cruel toward his own family. But how do we weigh that against the cruelty of his society, and of its abominable apparatus of slavery and white supremacy, for which he was trying to atone and make restitution? How does Asa’s “religious delusion” stack up against the much larger collective delusion that is white supremacy? These moral and political questions inevitably intrude into the interpretation of his right mind.5

The historical record on these questions is terribly one-sided. The perspective of the black kinfolk who became ensnared in Asa’s experiment never had a hearing. The moral judgments and medical speculations in this case came from within the elite white society Asa had turned against. Reading through the scattered probate and court records, one longs to hear the voices and opinions of the people he was “going among.” The little scraps left from Isaac Allman are just the tip of an iceberg we will never see. It is little wonder that the white jury in Jackson County ruled so definitely for the white plaintiffs, since the court functioned as a closed system in which their own “right mind” would remain unquestioned.

Asa’s strange deed was not merely about one man’s own quixotic search for righteousness. In order to “appear at the bar of God with clean hands,” as he hoped, he had to engage in a personal process of reparation that was directly at odds with the white power structure that ruled his society. If he had been in his right mind about it, society surely was not.

One of the most difficult legal hurdles for the reparations movement is simply the passage of time between then and now. The perpetrators of the crime of slavery all died long ago. Proving in court that their past actions are even partially to blame for social inequities and disparities in the present is extraordinarily difficult. In Fitzgerald v. Allman the problem was the opposite. The perpetrators were everywhere, and their victims still alive and in the neighborhood. The structural disparities of slavery carried over directly into the postwar period and tainted politics, economics, and justice.

Reparations of the kind Asa enacted, if expanded to a regional or national scale, would require massive transfers of wealth from whites to blacks. But even more fundamentally, this process of economic redistribution would require a revaluation of moral goods. No longer could white society maintain that its system of slavery had given moral and spiritual benefits to its victims that somehow balanced the labor and rights they had been forced to give away. Reparations required an honest accounting, one that did not spare the lies whites made up in order to hold on to their moral and fiscal balance sheets. Asa was willing to take this accounting to its logical conclusion, even if it meant impoverishing his own family.

The essential question Asa’s case poses for us in the present is whether white supremacy can be defeated without a structural change to these moral and fiscal balance sheets. In Asa’s mind, fundamental changes to the racial order still seemed imaginable, even as they were being violently contested by white reactionaries. It was still possible to believe that the rest of the world might catch up to him. Whether we will or won’t is the question that remains to be settled one hundred and fifty years later.

1 According to census records, Joseph lived on property adjoining the Fitzgeralds in 1850. In that year Sarah Norwood and her husband lived in neighboring Buncombe County, apparently with Venus and two other enslaved people. After the death of Sarah’s husband in 1852, she and her children and enslaved people moved in with Joseph. Tracing the location of the enslaved is difficult because the census’ “slave schedules” list ages but not names of individuals—only the names of the white owner or renter. Human error is also rampant in the federal census, especially for people of color, who dropped in and out of the count for a variety of reasons. Ages tend to be approximate for enslaved people and their kin because their natal networks were routinely disrupted. ↩

2 Land gifts from one family member to another typically used the phrasing “for natural love and affection,” while gifts to other entities like churches or schools often used the phrase “deed of gift,” both of which Fitzgerald avoided. ↩

3 For reasons of law and public relations the Fitzgeralds chose to sue Shelton rather than the more sympathetic orphans who actually owned the property. The Swanger orphans were not even given legal notice of the lawsuit. While it is possible that some of the witnesses that Shelton called did not testify in the earlier suit, the trial record overall is close enough in time and issue that it probably matches well to the earlier record. ↩

4 Both authors were antislavery but argued against civil disobedience. Thoreau famously argued against Paley in his Civil Disobedience. Asa seems to have chosen moderates who would make his idea appear less threatening to the social order. ↩

5 In his 1980 Esquire essay “Dark Days,” James Baldwin wrote, “To be black was to confront, and to be forced to alter, a condition forged in history. To be white was to be forced to digest a delusion called white supremacy.” ↩

sources

- Blumenthal, Susanna L. Law and the Modern Mind: Consciousness and Responsibility in American Legal Culture. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2016.

- Brophy, Alfred L. Reparations Pro & Con. New York: Oxford University Press, 2006.

- Chinn, Stuart. Recalibrating Reform: The Limits of Political Change. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2014.

- Estate files of J.A.B. Fitzgerald (Haywood County, 1878), North Carolina Estate Files, 1663–1979, and John B. Fitzgerald (Haywood County, 1878), North Carolina Estate Files, 1663–1979.

- Estate file of Lucas Benners (Craven County, 1837), North Carolina Estate Files, 1663–1979.

- Fitzgerald v. Allman, 82 N.C. 492 (N.C. 1880).

- Fitzgerald v. Shelton, 95 N.C. 519 (N.C. 1886).

- Foucault, Michel. Madness and Civilization: A History of Insanity in the Age of Reason. New York: Pantheon Books, 1965.

- Franklin, John Hope. The Free Negro in North Carolina, 1790–1860. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1943.

- Hilliard, Kathleen M. Masters, Slaves, and Exchange. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2014.

- Milewski, Melissa. Litigating Across the Color Line: Civil Cases Between Black and White Southerners from the End of Slavery to Civil Rights. New York: Oxford University Press, 2018.

- Nash, Steven E. Reconstruction’s Ragged Edge: The Politics of Postwar Life in the Southern Mountains. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2016.

- Ordronaux, John. “History and Philosophy of Medical Jurisprudence.” American Journal of Insanity 25, no. 2 (October 1868): 173–212.

- Randolph, Richard, Jr. “Richard Randolph’s Will,” in Centennial Anniversary of the Pennsylvania Society, for Promoting the Abolition of Slavery, the Relief of Free Negroes Unlawfully Held in Bondage, and for Improving the Condition of the African Race, 78–83. Philadelphia: Grant, Faires, & Rogers, 1876.

- Stephenson, Gilbert Thomas. Race Distinctions in American Law. New York: Appleton, 1910.