Fiume, c. 1890–1900. Photocrom Prints, Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress, Washington, DC.

We should at last be justified in not admitting the poet into a city that is going to be under good laws, because he awakens this part in the soul and nourishes it, and, by making it strong, destroys the calculating part, just as in a city when someone, by making wicked men mighty, turns the city over to them and corrupts the superior ones. Similarly, we shall say that the imitative poet produces a bad regime in the soul of each private man by making phantoms that are very far removed from the truth and by gratifying the soul’s foolish part, which doesn’t distinguish big from little but believes the same things are at one time big and another little.

—Plato, Republic

On September 12, 1919, Gabriele D’Annunzio (1863–1938) marched with three hundred irredentist supporters from Trieste to Fiume, where he declared himself Il Duce. Until the end of 1920, when shelling by the Royal Italian Navy forced D’Annunzio to flee, he ruled as dictator of this Dalmatian port city.

D’Annunzio, who was at the time Italy’s most popular poet, was just the man to lead a utopian takeover of the city. A 1930 Fox Movietone newsreel said he had “pursued a picturesque and frequently eccentric career which has endeared him to his countrymen and assured his place in history.”

After the fall of the Austro-Hungarian empire, Fiume—today the Croatian city of Rijeka—was claimed by both Italy and the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes. Even though Italy fought on the side of the Triple Entente during World War I, the Treaty of Versailles (and 1915’s secret Treaty of London) dictated that Fiume would be incorporated into a new Yugoslav state. Italians saw Fiume as their territory, claiming that Italians represented a majority of the population. (There were actually more Croats.)

D’Annunzio, who had lost sight in his right eye after a wartime plane crash, was one of the so-called Poetic Bombers, a group of Italians who dropped poems on their victims as well as bombs: “Your hour is passed. As our faith was the strongest, behold how our will prevails and will prevail until the end. The victorious combatants of Piave, the victorious combatants of Marna feel it, they know it, with an ecstasy that multiplies the impetus. But if the impetus were not enough, the number would be; and this is said for those that try fighting ten against one.”

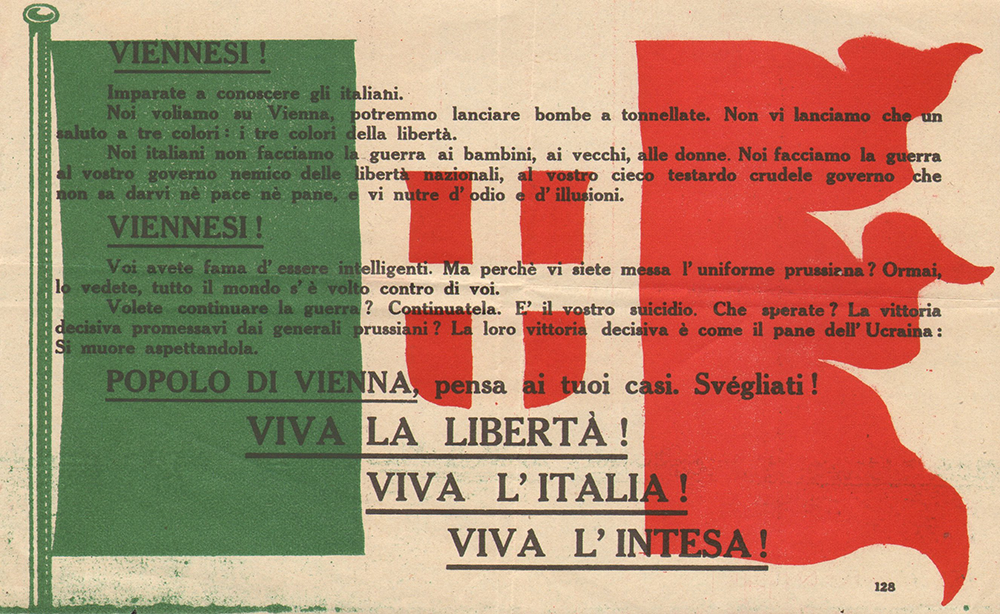

A year before entering Fiume, D’Annunzio led a squadron of biplanes to drop fifty thousand tricolor propaganda leaflets over the streets of Vienna in what is known as Volo su Vienna. The cards were not translated into German.

D’Annunzio was thus well positioned to set himself up in business. On September 8, 1920—nearly a year after he had arrived in Fiume—he proclaimed himself leader of the Italian Regency of Carnaro (named after the Golfo del Carnaro, the bay on which the city sits). D’Annunzio did not write the Constitution of Fiume—it was the work of the syndicalist and protofascist Alceste de Ambris—but he edited it and enlarged upon it as a poetic document of sovereignty. In the “Outline of a New Constitution for the Free State of Fiume,” dated August 27, 1920, D’Annunzio was the Commandant:

The Commandant

43. When the province is in extreme peril and sees that her safety depends on the will and devotion of one man who is capable of rousing and of leading all the forces of the people in a united and victorious effort, the National Council in solemn conclave in the Arengo may, voting by word of mouth, nominate a Commandant and transmit to him supreme authority without appeal. The Council decides the period, long or short, during which he is to rule not forgetting that in the Roman Republic the dictatorship lasted six months.44. During the period of his rule, the Commandant holds all powers—political and military, legislative and executive. The holders of executive power assume the office of commissaries and secretaries under him.

45. On the expiration of the period of rule, the National Council again assembles and decides: to confirm the Commandant in his office, or else to substitute another citizen in his place, or else to depose him, or even to banish him.

46. Any citizen holding political rights, whether he have any office in the province or not, may be elected to the supreme office.

Fiumianism grew out of Futurist and anti-bourgeois movements. D’Annunzio combined a robust nationalist identity in Italy with fin de siècle Nietzschianism. With its clownish epaulettes and opera buffa emotiveness, the government verged on the preposterous.

Still, it was a poetocracy. In article 65 of the Fiume Constitution D’Annunzio mandates that in “every commune of the province there will be a choral society and an orchestra subsidized by the state. In the city of Fiume, the College of Aediles will be commissioned to erect a great concert hall, accommodating an audience of at least ten thousand with tiers of seats and ample space for choir and orchestra. The great orchestral and choral celebrations will be entirely free—in the language of the Church—a gift of God.”

The logical result of fascism, says Walter Benjamin, “is the introduction of aesthetics into political life.” Subsequent fascist regimes lacked D’Annunzio’s flair. American architect Philip Johnson and his fellow Museum of Modern Art alum Alan Blackburn had hoped to aestheticize Louisiana senator Huey Long, considering the Kingfish capable of leading a fascist revolution in America. “I’m leaving,” Johnson told friends in New York in 1935, “to be Huey Long’s minister of fine arts.” Johnson and Blackburn designed uniforms and symbols for Long’s campaign and drove Johnson’s Packard to Baton Rouge, where they were sent back north by an aide to “organize Ohio.” (Johnson’s family owned a farm in New London, Ohio.)

D’Annunzio initiated the Roman salute and dressed his henchmen in black shirts. He took the title of Duce from the Latin dux, cognate with duke. He designed the flag (the Regency of Carnaro’s motto was Quis contra nos?—Who stands against us?). His image even appeared on postage stamps of the Italian Province of Carnaro. He exalted war and ruthlessness and called for a “revolution of the body.” D’Annunzio’s aesthetic realm in turn influenced Benito Mussolini’s fascist government, which came to power in 1922’s March on Rome. The Italian fascists held sway in turn over subsequent fascist regimes. Spanish general Francisco Franco, Portuguese dictator Antonio Salazar, and Japanese admiral Tojo Hideki all aspired (with lesser success) to the aesthetic power of Mussolini, and of D’Annunzio before him.

“They intended Fiume to lead all the peoples of the earth toward the future,” wrote the Futurist poet and fellow traveler Mario Carli in his 1922 novel, Trillirí, “an island of wonders that was to travel the oceans, taking its shining light to the continents drowning in the darkness of brutal capitalist speculation. In the City of Carnaro this group of enlightened men, fanatics, mystic forerunners, managed to conjure up that atmosphere of passion for the future and poetic rebellion against the old faiths and ancient formulas that has been given the name of fiumanism.”

The revolutionary rhetoric of fiumianism caused concern within the Italian government, which viewed it as lawless and wanton. As Antonio Gramsci wrote:

D’Annunzio, the head of the legionnaires, was depicted as a madman, a histrionic enemy of the homeland and an instigator of civil war, opposed to all human and civil laws. To further its own ends, the government roused the most intimate and profound sentiments in the collective consciousness: the sanctity of the family violated, fraternal blood coldly spilled, the integrity and liberty of the people left at the mercy of a mob of drunken, lust-crazed soldiers, girlhood contaminated by the most wanton sexual urges. By planting these ideas the government managed to achieve a near perfect consensus: public opinion was manipulated with unprecedented ease.

By November 1920 the new Italian prime minister, Giovanni Giolitti, ordered D’Annunzio to leave Fiume. On Christmas Eve a battleship shelled D’Annunzio’s palace, and he retired to Il Vittoriale, his megalomaniacal villa in Lombardy.

D’Annunzio’s relationship with Mussolini was difficult. He supported the Italian dictator but opposed his alliance with Adolf Hitler. Mussolini recognized the poet’s intelligence and bravura but still considered him a potential rival, and assigned a police inspector to keep an eye on him. D’Annunzio was nevertheless an old man when he left Fiume and perhaps less a threat than was perceived. Mussolini rewarded D’Annunzio with a pension, a title (the Prince of Monteneveso), and a national edition of his works. The poet remained at his villa, where he died, six months before the fascists issued their Manifesto della razza (Manifesto of Race), which led to the seizure of the property of Italian Jews.