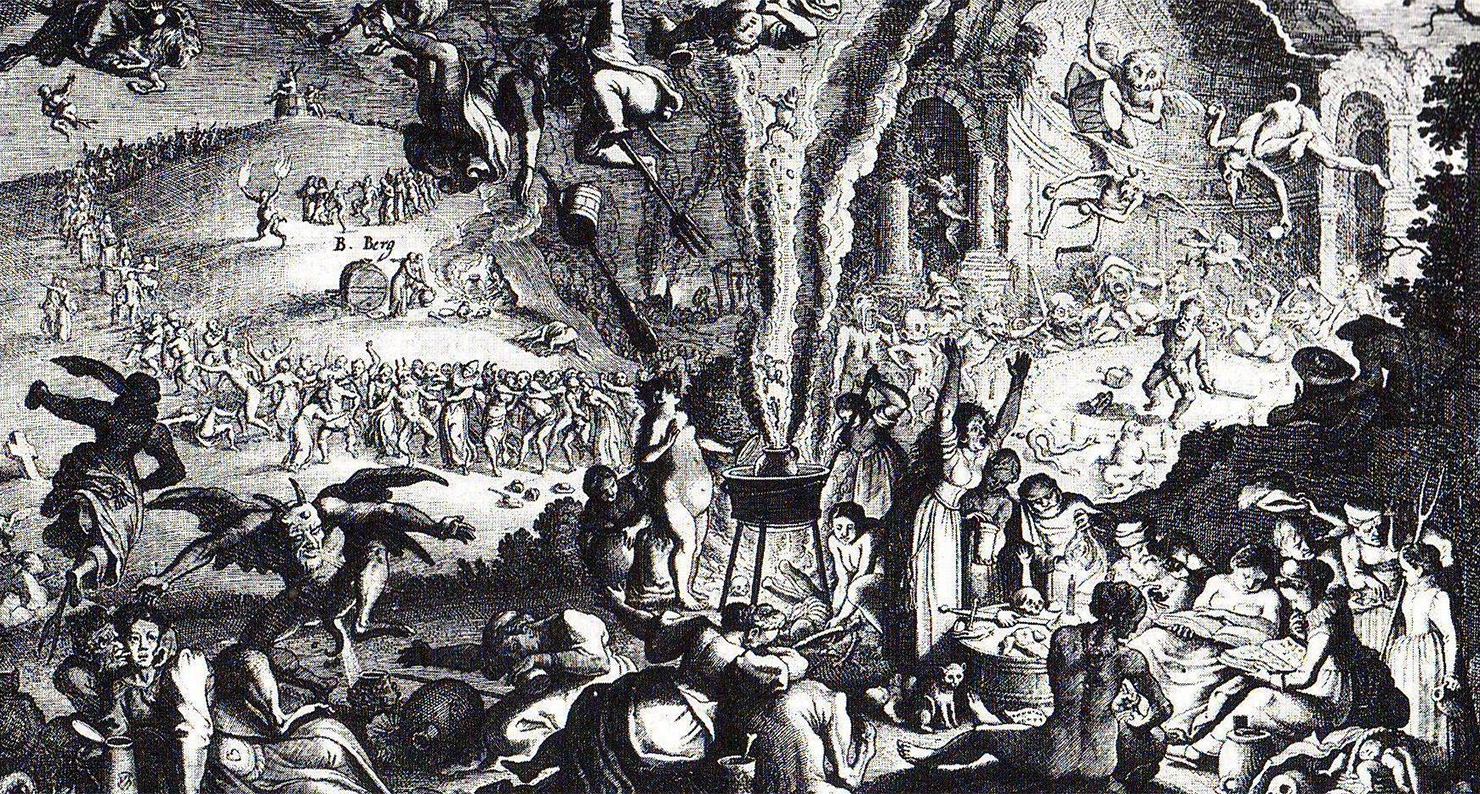

Witches’ Sabbath on Mount Brocken, by Michael Herr, 1650. Germanisches Nationalmuseum, Nuremberg, Germany.

The old woman, dressed in a sari and covered in silver bangles, placed a basket beneath my eyes and opened the lid. Inside, dozens of baby cobras writhed. I stood in a crowded market in the town of Shimla, in the foothills of the Himalayas, waiting for my wife and my daughter Shoshie while they shopped in one of the small stores that packed the narrow lane. Pulling stroller duty with our youngest daughter, Naomi, I had been trying to stay out of the way of the steady flow of people crossing my path in both directions. The woman said something to me in a language I didn’t understand, and held out one hand while keeping the basket of snakes close to her chest with the other. A basket of cobras is more effective a panhandling technique than most, and so I reached into my pocket to give her some rupees.

I used to catch snakes as a kid in Ohio and snakes don’t bother me. Spiders either. I have a healthy fear of heights, but nothing I’d classify as a phobia. I’ve even had a rifle held on me in Mindanao and I think I handled myself with an aplomb that surprised me. Not that I’m brave. You wouldn’t look at me, six feet tall (barely) with a bit of a gut and say, “Now that’s a macho dude.” I’m just saying that the things that should scare me usually don’t and the things that shouldn’t scare me sometimes do. By “things that shouldn’t scare me,” I mean largely the supernatural.

At that moment, my wife emerged from the shop along the way and she signaled me to join her. I asked her to wait but she seemed impatient and was already moving along in the crowd. She has a habit of disappearing, and while that’s okay in a grocery store, I didn’t want to lose her in a crowd in India. I put my wallet back in my pocket and the woman with the basket of snakes let out a horrified shriek as if I had bitten her, followed by a cascade of words for which I needed no translator. As I picked my way through the narrow street, she followed, keeping up a steady flow of shouts. People around us stopped and gaped. Part of me wanted to simply give her some money, but ahead of me, Margie was already being swallowed up by the swell of people and I didn’t want to lose her.

When I finally caught up with her, she asked me what that was about back there and I told her that I thought I had just been cursed. She laughed and waved the curse away, though of the two of us, she believes more readily in curses than I do. Just not on that day.

Margie comes from Mindanao. The only place in the Philippines more likely to leave you accursed is the fabled island of Siquijor, the Isla del Fuego of the Spanish, where black magic and white magic practitioners reportedly abound. Curses run rampant in Margie’s family line. The chief purveyor of curses is her Evil Auntie Neneng (“Evil” is an adjective that nearly always appends her name). Evil Auntie Neneng is the widow of Uncle Joseph, a datu of the Manobo tribe and a former Marcos-era songressman who died, by some accounts, of complications from diabetes, but more certainly died because he was cursed by Evil Auntie Neneng, who was neither Manobo nor grief-stricken at his death and who immediately took up with another man and started grabbing the family lands that rightfully belonged to Margie’s mother and her siblings. Tales of Neneng’s machinations are legion. Over the years she has employed thugs to murder those who would stand in her way and has sought more arcane methods to fulfill her agenda as well.

Margie’s Auntie Jovan, for instance, fell deathly ill one day for no apparent reason. Her head pounded and she could barely stand. After three days of this, a friend of hers sought the help of an itinerant Indonesian healer who, upon gazing into his crystal ball, saw a coffin. He determined that Jovan had been cursed and that it was a good thing that he did not see a wreath of flowers laid upon that coffin or his help would have come too late. He instructed the friend to bring him such a wreath to counteract the spell. When he described the person who had cursed Jovan, the description perfectly fit Neneng. Of course.

If I seem skeptical, well, that’s the nature of curses, isn’t it? Margie is skeptical of my curses and I’m skeptical of hers. That’s the default when it comes to curses. It’s a matter of belief, goes the conventional wisdom, and if you don’t believe you won’t be affected. And it’s easy to disbelieve if you’re not the one who’s been cursed.

Curses most often belong to the dispossessed, their last and ultimate defense. The best curses come from those who have a history of oppression. Think of the Roma in Europe, Haitians, Afro-Cubans, “Can curses pierce the clouds and enter heaven?” Queen Margaret asks in Richard III. A curse is a last resort, when earthly justice fails, an act of desperate rage that requires no surefire answer from God as to its efficacy. The curser curses first and takes credit later. In Margaret’s case, her question is rhetorical. She expects no answer except in results. Both her husband and her son have been murdered. What does she have to lose? “Why, then, give way, dull clouds, to my quick curses!” she cries. In her case, God listens and all those who have had a hand in the deaths of her husband and son eventually meet their ends just as she has predicted.

Rarely are the effects of a curse quite so transparent or tidy. Some of the best curses arguably come from my people, the Jews, not Israelis, but the Jews of the Shtetl, those who cursed in Yiddish. Oddly, on the day of my brother’s wedding in 1980, my great Uncles Morty and Bill sat with me on my grandmother’s porch in Long Beach, New York, and taught me all the Yiddish curses they knew. To this day, I’m not sure why they chose a happy occasion on which to spout curses, except that this side of my family was a dour lot, and too much happiness perhaps put them ill at ease and they needed to counter with some good old-fashioned spite:

Lie with your head in crap and grow like an onion

May you give birth to a trolley car.

May you have two beds and a fever in each.

If the curses of the Jews are colorful, they’re also the easily ignored. How can you take such clever curses seriously? They’re infected by a built-in self consciousness. May you give birth to a trolley car? The forebears of my people, the Israelites, cursed better or at least more earnestly. Here, the prophet Elisha curses a bunch of rambunctious boys.

And on his way up to Beth-El, he encountered some small boys from the city who mocked him: “Come up, Baldy! Come up, Baldy!” When he looked behind and saw them, he cursed the boys in the name of the Lord and then from the wildwood emerged two she-bears who tore apart forty-two of the children. From there, he headed to Mt. Carmel and afterwards returned to Samaria. (Kings 2, 23-25, my translation).

The crime hardly seems to matter—it’s the sting of the slight that counts. Male-pattern baldness is no less a reason to call on God’s vengeance than the murder of your husband and son. What might seem to a bystander as the disproportionate use of force is for Heaven to balance, not us poor mortals who might see such a scene as, well, overkill.

The word wildwood is most often translated as simply “woods” or “forest,” but the notion of wildness needs to be stressed, I think. It’s the notion of the heavens as elemental, the curse as an extension of nature, the wildness of a tornado or a hurricane or she-bears. The curse is the force of madness and rage, a different frequency from that of the supplicant murmuring gently prayers. Curses are not sensible; they are not uttered in moments of reflection, and so the results can be messy.

Zora Neale Hurston records a curse from the Algiers section of New Orleans so long and mean that simply hearing it would have made me faint dead away:

“That the South wind shall scorch their bodies and make them wither and shall not be tempered to them,” it reads in part. “That the North wind shall freeze their blood and numb their muscles and that it shall not be tempered to them. That the West wind shall blow away their life’s breath and will not leave their hair grow, and that their finger nails shall fall off and their bones shall crumble. That the East wind shall make their minds grow dark, their sight shall fail and their seed dry up so that they shall not multiply.” This is only a fraction of the text of the curse, which ends despairingly, “O Man God, I ask you for all these things because they have dragged me in the dust and destroyed my good name; broken my heart and caused me to curse the day I was born. So be it.”

Despair and rage and dispossession find some solace in words and gestures towards an unseen hand that is much stronger than ours, and if it’s not stronger or it refuses to slap silly our oppressors, then the words themselves have the power to make your blood pressure rise, whatever anger that lies inside you, rise volcanic to the surface. And that in itself is a partial remedy for impotent rage. The simple channeling of that anger into a funnel of spite. There’s something undeniably beautiful about a well-worded curse.

Go ahead. Give it a try.

In my own case, I put some curses on a group of summer campers in New Hampshire when I was eleven. I belonged at the time to an arcane secret society called “The Silver Sword Society.” I was its only member and I have no idea how I came up with that name or the method of cursing people I didn’t like—running them through with an invisible (but apparently silver) sword and then waiting for the curse to take effect. Every time I cursed someone, something bad happened almost immediately. I made one of my bunkmates so hysterical with my curses (after he’d dislocated a finger playing hot potato, something that could have been caused by nothing other than my curse, of course!), he, a hefty boy, sat on my chest until I agreed to remove the many swords with which I had impaled him. Later that day, I was visited by the head counselor Marty who solemnly warned me to “stop it already!” with the curses. I doubt he took the curses seriously, but he took the disruption of camp life quite seriously—drunk on my power, I had become a kind of curse kingpin in the days preceding his appeal to me, campers visiting me with requests in return for candy bars. Although my cursing days were over, I learned that the line of influence in this world is not always visible, rational, or wholly explicable. From my anthropology courses in my college career, I subsequently learned that in some societies, a curse is the only logical explanation for someone’s misfortune.

In the several years since the woman in India cursed me, how has my life been affected? This is a tough question. My fortunes have not been terrible. A book I published that Spring was met with good reviews but somewhat lackluster sales. A movie deal was struck and then fell through. I suffered a few colds, an inexplicable rash, a mild bout of depression. I was not rich yet and I was getting less handsome by the day. I believed that the old woman’s magic was working. After learning that I had been cursed, a friend remarked, “Your life seems to be going pretty well.”

“Ah, but how much better would my life be if I hadn’t been cursed?”

This is a difficult question to answer, but one I determined to determine. While in Hong Kong, I asked a friend, a reasonable person, if she knew of anyone who might be able to remove a curse? I’ve known this person for a decade, but I’ve never seen such a look on her face—she seemed to be reevaluating every moment of our long friendship. “A curse? No, I don’t.” And that was the end of that.

I finally had my chance when I brought a group of students to the Philippines and was making up the itinerary. I chose to visit Siquijor for a few days. Here, at last, was the opportunity to have my curse removed.

The healer we arranged to meet was a woman in her eighties who lived at the end of a dirt road in the hills of Siquijor. Her shack was a multi-purpose facility. Amid chickens and dogs, a few men sat around a videoke machine with large bottles of Red Horse beer. As I made my way across the courtyard, I banged my head smack into a post, probably not the most auspicious omen, but I tried to chalk it up to my clumsiness, rather than cosmic irony. On the other side of the ersatz karaoke bar was a small room that stank of ammonia from below the bamboo floor where the chickens hid from the sun, but otherwise the room was neat if Spartan, its only decoration a calendar from Japan. From inside a dark room adjacent to the clinic wafted the sounds of the NBA playoffs, no more incongruous than the adjacent karaoke bar. The old woman, dressed rather stylishly in a purple blouse, her gray hair pulled back with a scrunchy into a ponytail, worked on a client, a woman suffering from asthma while I waited on a bamboo bench and watched her work. With a wooden straw, she blew into a jar of clear water while moving the jar slowly around the woman’s body, the sounds of the bubbles mixed with the old woman’s grunts and sharp intakes of breath. I was impressed. There were no snakes, but it was still tactile and sensuous, and this is what you want when working with magic, to physicalize the mysterious and ineffable. Otherwise, how do you know it’s working? A smooth stone lay at the bottom of the jar—the stone, she said, had been given to her by the Santo Nino. The stone was cold and incredibly heavy, my guide said. He had touched it once. Her brand of magic was an amalgam of local animism and Catholicism; she crossed herself before she began her work. Of all Western religions, Catholicism is perhaps best suited to mix and match with other ancient rituals and beliefs, its pantheon of saints, its incense, its holy water, all tactile and visible manifestations of the mysterious at work in the world. Of all Western religions, none allow more for the intercession of the supernatural in the everyday lives of mortals. A friend of mine prays to Saint Jude, the patron Saint of Lost Causes to find parking spaces, and she claims he always comes through for her. The trick of crossing your fingers for good luck originated in the Middle Ages as a quick sign of the cross to ward off the devil and evil spirits. Certainly, even the most skeptical among us have crossed our fingers.

As the woman blew on her straw, the water started growing cloudy and little specks of dirt floated in the jar. She stopped blowing and examined the jar, withdrew a piece of something and showed it to her patient, then rinsed the jar clean and filled it with water again, repeating the process of blowing into the water until it clouded again.

When it was my turn, my guide asked me what was wrong?

A curse, I said. A barang.

This was not her specialty, it turned out. She was better with asthma.

“What part of the body is affected?” she wanted to know.

That was hard to tell. “I don’t know,” I said. “Maybe the mind.”

She nodded. “Fearful,” she surmised.

She started in on me, blowing bubbles along my shoulder, my chest, my groin. My case was acute. I could have guessed as much. She used three jars of water on me, each one clouding up, big chunks of flotsam swirling in the water as she grunted and blew. Oddly, I didn’t feel even slightly curious where the junk was coming from.

I should have been at least a tad curious. I’m related directly to Houdini. He was my great grandmother’s nephew. I suppose I was letting him down in my complete lack of interest in how the clear water became dirty. He spent much of his professional career debunking psychics, but only because he wanted so desperately to believe in an afterlife so that he could communicate with his departed mother. Psychics hated him and he was the object of many a curse. Who knows if they eventually worked? He did, after all, meet his end on Halloween.

I suppose a skeptic would assume the junk in the jar originated in the straw or that she hid it in her cheeks. Probably. Maybe. I don’t know. I couldn’t tell. At one point, she fished out a dark piece of something and said it looked like a scale of some sort. Before I could get too excited by the coincidence, I remembered that I had mentioned snakes when I was explaining the nature of my malady. She placed the dark thing on my finger and I studied it. Definitely not a scale but a soggy piece of wood. I passed it around the room, where some of my students were looking on. A few touched it, but most refused.

When the old woman had finished, she blew down my neck and said a prayer. I asked her if the curse was removed.

“Wala,” she said. All gone.

Still, I bought a jar of special coconut oil from her, made with three hundred herbs, gathered during Holy Week and prepared on Black Saturday. “And rituals,” my guide said. “There are rituals for this.”

Meanwhile, Margie was asking around for a panagang, protection to counter the powerful spells of Evil Auntie Neneng that were killing or almost killing Margie’s relatives. She wanted to find someone who specialized in barang, not asthma. Yes, there are such people, she was told, but they live high up in the mountains. They always do. I’m not sure why. But if you want someone really powerful, don’t expect to find her in a karaoke bar. You have to do some trekking. Unfortunately, we had limited time, so dispelling the spells of Evil Auntie Neneng would have to wait for another visit.

Of course, the question remains whether my curse was removed or not. I wondered in subsequent days whether an Indian curse could be removed by a Filipino healer who specializes in asthma. I even wondered whether I had indeed been cursed at all or if my woes, often indefinable, could be relegated to the nefarious and incurable human condition of daily life.

A couple of days later on the island of Bohol, while walking in my flip flops on a side street, I severely gashed my big toe on a rock. Later that day, my eye inexplicably swelled shut. And that evening, while walking home from a bar on the beach, I gashed my other big toe open on another rock, this time so badly that my flip flop was awash in blood and I left a rather ghastly trail all the way back to our hotel. I fretted that my curse seemed stronger than ever.

Six weeks later, I traveled to Cuba—that summer found me careening wildly from one point of the globe to the other, mostly for reasons to do with my teaching and writing. In Cuba, I was scouting a workshop of undergraduates I would lead later in the year. One of the stops on my itinerary that July was La Regla Church, one of the centers of Santeria belief in Cuba, and a short ferry ride across Havana’s harbor. Of West African origin and hybridized by Afro-Cuban slaves over several hundred years, Santeria is another manifestation of the dispossessed taking control of their lives in cosmic fashion, and another free mixing of Catholicism and animism. As my guide led me to the church, we passed a smattering of women seated on the curbside, calling to us to have our fortunes told. My guide, Yunelbis, a thirty-ish woman dressed smartly in her official guide shirt of light blue, jeans, and a pair of designer glass knock-offs, scoffed at one woman’s entreaties to listen to her. “She’s maybe a little mad,” Yunie told me in English as the woman tried to tell her something that would make her pause and listen and linger and presumably pay.

I’ve seen many churches in my day—undoubtedly more churches than synagogues because churches are on any tour in nearly every land I have visited. La Regla Church itself was not the most impressive I’ve seen, but the fervor of the supplicants inside was more impressive than what I’ve witnessed under the echo-chamber domes of Europe’s cathedrals, dozens of men and women praying passionately before icons, a hundred candles burning, each one a private supplication, human hope as always wafting upward to a vanishing point, while oddly enough, piped-in Western music played “All by Myself” by Eric Carmen. Yunie pointed out the Santeras and Santeros, woman and men dressed all in white from head to toe—the religion had undergone a revival after originally being suppressed by the Communist Party. Now, even a number of the ruling elite are among believers in Santeria.

When we left the church, another woman seated on a low wall appealed for us to listen to her—Yunie had seemed so skeptical before that I assumed she would brush aside this woman as she had the first one, but she didn’t. As if, well, in a spell, Yunie walked directly over to the woman and I followed. The woman, anywhere from forty to sixty years old, had a yellow kerchief tied around her hair and wore half a dozen bead necklaces, a couple of beaded bracelets and jeans with chalk-like patterns that recalled, perhaps unintentionally, leg bones. Her name was Maritza, and she sat beside her own portable altar, at the center of which a most impressive doll resided. The doll’s skin was dark like Maritza’s and its lips were red and it wore glasses. Like Maritza, it too wore a kerchief, but one that was pointed in the back, somewhat more regal, like a Pope’s mitre. Its ruffled yellow skirt was arrayed around it, and the doll, too, wore necklaces of beads. Her name was Francisca and she was the spirit with whom Maritza spoke in order to divine. Beside the doll stood a bottle of cacao oil on one side, and a statue of the Virgin Mary holding the Baby Jesus on the other.

I figured that it wouldn’t hurt to get my curse removed again. Perhaps I would spend the rest of my life, traveling from one center of animism to another, trying to get my curse removed. This compulsion in itself might be a kind of curse. I told her through Yunie that I had been cursed by an old woman in India. “Yes,” she said. “It’s a powerful curse. Very powerful.” I knew exactly what “very powerful” meant, and I took out my wallet.

She told me that I had stepped on something and that I was suffering health problems in my foot.

Upon reflection, it does seem to me now that the woman in India with the snakes cursed my feet. This makes perfect sense. As I ran away from her in the market, she might logically (if logic has anything to do with it), curse the feet that were taking me away from her. Not only had I gashed both my toes on the same day, but recently I’d started to suffer from an intense pain in my left heel, a condition that has since been diagnosed by my doctor as Achilles’ tendonitis. I asked Maritza which foot was the one giving me problems. She brushed her hands along both legs, stood back and pointed decisively to my right foot. I couldn’t be happier that she guessed wrong. If she had guessed right, I’d be a complete mess by now, instead of merely a partial mess.

We went ahead with the ritual then. She tossed some cowrie shells . The shells landed right side up and this, she said, meant I had the “blessing of Olofi,” the Santeria name for the Almighty. She proceeded to rub cacao oil on my legs, told me to make the sign of the cross—hmm, not something I had much practice at. Mine was more like “the mark of Zorro. “ And she draped me with a white shell necklace and told me I needed to wear it always, but especially on Mondays and Fridays. Then she told me to give her some money and a beso, a kiss, on the cheek.

Intercession, of whatever variety, almost always feels good, whether it actually does good or not. While Christopher Hitchens, a devout atheist, expressly forbid Christians to pray for him when he was diagnosed with esophageal cancer, I say, bring them on, the more prayers, the better. Send me your talismans, too. I’m certain I’ve been cursed, as you undoubtedly have been cursed by someone somewhere at some time. Assume it’s so and see if you can break the spell. My most recent foot ailment has practically healed though I don’t wear my necklace very often, not even on Mondays and Fridays. I’d like to think at this point I’m curse-free, but I’ll never know because it’s just as difficult to tell whether you’ve been healed as whether you’ve been cursed. Someday, I’ll succumb to something. There’s no escape. Even now, I’m having a little trouble breathing.