Royal Avenue, Chelsea, by William Evelyn Osborn, c. 1900. Photograph © Tate (CC-BY-NC-ND 3.0).

“Toward the evening of a gone world, the light of its last summer pouring into a Chelsea street found and suffused the red waistcoat of Henry James, lord of decorum, en promenade, exposing his Boston niece to the tone of things.”

Hugh Kenner’s magnum opus, The Pound Era, begins with this rosewater tableau. A sentence “to be rolled about on the tongue,” Kenner wrote gleefully in a letter to his literary compatriot, Guy Davenport, after having taken a month to write that one opening line (“breaking Joyce’s snail-pace record of fifteen words in a day”).

Born in 1923, the year after the publication of James Joyce’s Ulysses, Kenner spent his life charting the artistic developments of the twentieth century. He is known mostly for his work on the modernists—culminating in 1971 with The Pound Era, a monumental critical study that placed Ezra Pound at the center of the early twentieth century’s avant-garde, revitalizing the image of the poet-cum-fascist-provocateur just before Pound’s death. Kenner is anything but one-note, though: he wrote on a vast array of other topics—everything from geodesic math to animation pioneer Chuck Jones.

The Pound Era’s shimmering first section, “Ghosts and Benedictions,” depicts a scene from June 1914 in which Pound meets Henry James on the streets of London. “He liked James,” Kenner wrote of the fledgling poet, “he wondered at James, as at a narwhal disporting.”

It’s a memorable image—a perfect descriptor of the marvel with which the young Pound might have looked upon his curious literary elder.1 Kenner sketched the scene with Jamesian flourish. The “fundamental principle” of Kenner’s critical output, by his own admission, was that he “writes about them in their own voices,” often aping the style and aesthetics of the author he was discussing. Speaking of that first sentence of The Pound Era, he hoped Davenport would “not miss the deliberate system of allusions in forty-one words, the studied presence of a foreign phrase, its effect in prolonging the rhythm with a touch of Jamesian delay, the fact that the subject of the sentence is ‘light.’ ” Throughout the opening section, Kenner co-opted with exacting precision James’ attention to vivid detail, affinity for unspooling sentences, and astute emotional understanding of his characters’ inner lives, offered in hints and hushes. As a result, Kenner’s writing seems simultaneously novelistic and journalistic. Rarely are we able to feel—in effect, to be—present at such a meeting of literary giants.

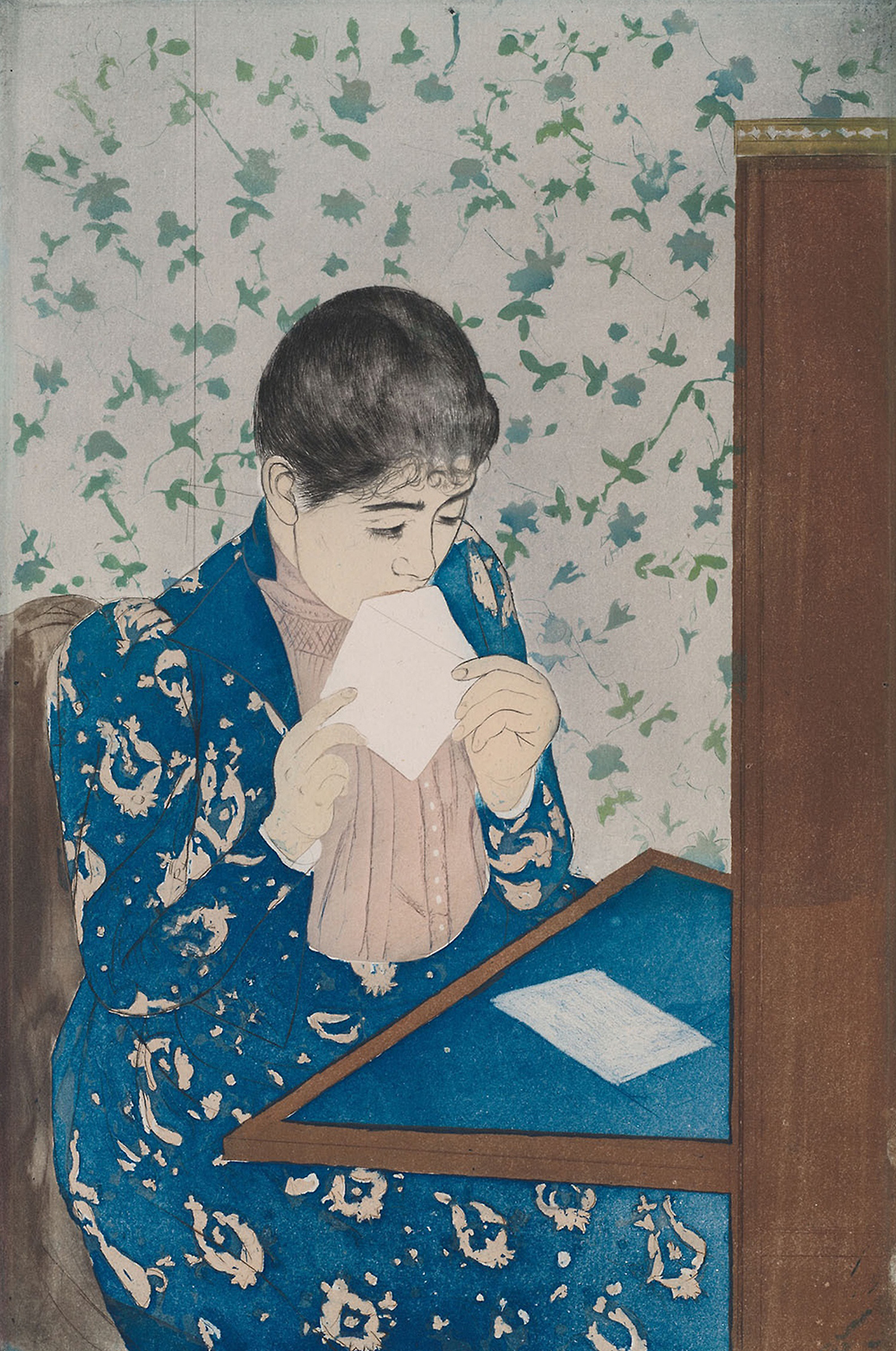

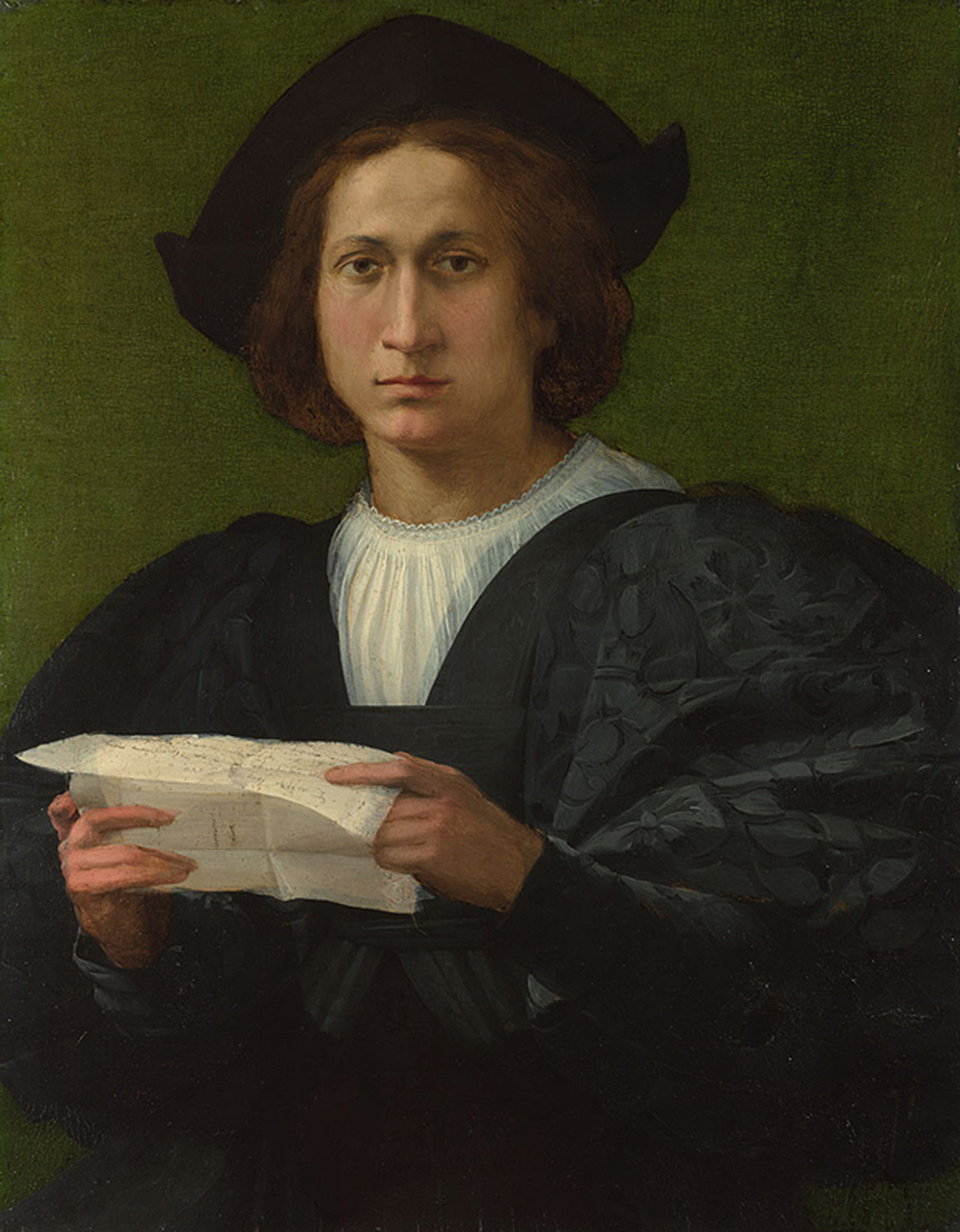

Kenner’s book was built from these tiny details and poetic vignettes, scraps gleaned not just from his reading of Pound’s work but also from countless interviews and letters. The letters of artists and intellectuals not only give us firsthand insight into the minds and manners of the men and women who moved culture forward, but often they also offer a documented meeting of the minds—one major thinker conversing with another in the permanence of ink rather than in the vanishing airs of conversation en promenade on London streets or amid a haze of smoke in some Parisian café.

Just as Kenner obsessed over the letters of Pound and his modernist kin, I recently found myself obsessing over the exciting, new, nearly two-thousand-page compilation of the correspondence between Kenner and Davenport.

Davenport was a few years Kenner’s junior, but they shared much in common. Like his frequent epistolary interlocutor, Davenport charted the artistic developments of the twentieth century as a critic of extreme breadth and depth. Also like Kenner, he saw Pound as central to the project of modernism. Both were interested in how form could function as an embodiment of textual ideas: “A work of art is a form that articulates forces,” wrote Davenport, “making them intelligible.” But Davenport—who, unlike Kenner, also found time to be a fiction writer, poet, and painter—became known for his idiosyncratic narrative assemblages, chimeras of fiction, history, poetry, and illustration.

In the letters of Kenner and Davenport, as in those of artists and intellectuals throughout history, we meet first-draft people and are introduced to their first-draft ideas. But these shards of insight are surrounded by “eloquent absences” and “ghosts unfulfilled,” using Kenner’s phrasing: “the accessible world a domain of ghosts and shadows and half-men.”

The two-volume collection of letters, Questioning Minds: The Letters of Guy Davenport and Hugh Kenner, published by Counterpoint, gives readers unprecedented access to two of the greatest interpreters of the modernist legacy working parallel, both independently and jointly, like a pair of riders on a tandem bike. Consider the tandem cyclists as they pass, supreme specialists, transfiguring together, each with their own bodies and minds, their own idiosyncratic actions, but in sync, in unison, the act of a movement—in this case, the movement of modernism, of which they were among its most preeminent readers, fans, critics.

The correspondents’ mutual respect and unending curiosity comes across in the constant praise they heaped upon each other. Early on in their correspondence, in January 1962, Davenport expressed his approval of Kenner’s recent book on Samuel Beckett:

Beckett is a masterpiece!!!!! Every bloody sentence INTERESTING. There’s simply nobody w/in a hundred miles of your excellence. Nobody.

A month later, Kenner reciprocated, sending kind words in Davenport’s direction:

I meant to say in my last letter that your Tarzan item suggests a wholly new genre in U.S. intelleckshul journalism, for the development and perpetuation of which you are THE man most obviously qualified.

Their mutual praise, though sometimes verging on the hyperbolic, never rings false. Each liked the other, wondered at the other, as at a narwhal disporting.

Because of Kenner and Davenport’s shared sense of trust, these letters show both scholars working out their thoughts, unafraid to express ideas that are incomplete, messy, even downright wrong. After Kenner outlined some ideas he wanted to include in one of the books they worked on together, he admitted, “Many of these mutually incompatible, I know. Just stabs in the dark.”

The dashed-off quality of a letter invites such stabs in the dark. In comparison to an essay—which needs a thesis and some sort of structure, and is written over hours, days, weeks, sometimes years—a letter is a half-formed thing, made in the warm lamplight of a moment, and describing nothing definitively except its moment. Whereas an essay is an expression of pride—those of us who write and publish them are either explicitly or implicitly saying, “Here are my thoughts, laid out in a crystallized argument, which I deign to offer up for public consumption”—a letter is a thing of shame, often betraying a writer’s insecurities, uncertainties, eccentricities, contradictions, imperfections, antipathies, and prejudices, unadorned with the normal niceties and lacking any softened edges. “Sorry for all the acid I manage to spill into letters,” Davenport wrote.

The letter exists at the midway point between the measured formal cohesion of the essay and the loose ephemeral buzz of conversation. One of the many reasons why intelligent people often hold the art of conversation in such high esteem is that a dialogue is where one can test out ideas—a place to be unsure, inconsistent, problematic. It isn’t just a joy but a moral imperative to think and speak recklessly, for one can only pursue truth and beauty, navigate this nuanced and mysterious world, investigate eternal existential questions, explore new frontiers, and move the culture forward—the duties of the artist and thinker—if one is willing to risk impropriety, sounding foolish, being “off-brand.” But trust in both the freedom offered by conversation and the charity of the person with whom one is conversing is essential here. One can’t traverse uncharted territory if one is always afraid of crossing an uncrossable line, never to be able to return.

Letters borrow this moral imperative from conversation. The letters of history’s greatest thinkers then become a case study in documented recklessness. It is in this recklessness—with little care for public appearance, performed righteousness, possible offense, or fabricated pretense—that a person is able to try out ideas that may otherwise never find adequate expression.

Joseph Killorin, the man handpicked by modernist writer Conrad Aiken to collect and edit his letters, explained in the introduction to Aiken’s Selected Letters that “to write a letter was a way to ‘fix’ the hourly news of consciousness.” In their missives, as in the letters of many artists and intellectuals, Kenner and Davenport responded to the daily minutiae of existence (“exams breathe down one’s neck”); gossiped about their contemporaries (“Harold Bloom, getting it all wrong as usual”); expressed their dynamic opinions on art (“I realized only the other day that the kite in the last chapter of Murphy is a transfigured bicycle, the rhomboid frame, wheelless and aloft: one of the master’s wildest comic ideas”); reviewed the touchstones of contemporary culture (“Chaplin’s Countess [has not] a cinematic idea, from end to end, and not one funny sequence”); wrestled with the everyday Antaeuses of an examined life (“I blame the emerods on all that has provoked my silent rage at the world”); brainstormed potential projects (“May end up writing a book (groan) on the symbolism of rocks and ruins”); and dashed off incipient ideas (“Thought is a labyrinth”).

Some of these nascent concepts were expanded and shaped into their public work. “Thought is a labyrinth,” a phrase Davenport wrote in a letter discussing the death of William Carlos Williams, takes on a life of its own. The line tickled Kenner enough that he responded: “ ‘Thought is a labyrinth.’ The Pound Era could well close with those words.” Further on in the same letter Kenner confirmed: “In fact I think you have supplied me with an ending phrase.” The book uses those borrowed words as a sort of closing prayer. In this way, the letters of great thinkers not only represent the first drafts of their philosophies but also highlight the ways in which a first draft gets revised through dialogue with respected readers, in a kind of informal workshopping.

Sometimes, though, letters offer grand philosophical ideas that, for some reason or another, a writer never chooses to express publicly in a more formal, fleshed-out way. Though many of the best letter writers—Virginia Woolf, Franz Kafka, Oscar Wilde, Walter Benjamin, among others—dashed off diamond ideas with little regard to their polish or shine, John Keats, whom Davenport called in a letter to Kenner “discoverer of the vases, their enigmatic beauty,” was the undisputed master of expressing compelling philosophical ideas in a single sentence or paragraph in one of his letters, never to be returned to again, never to be expounded upon, never to achieve the deathly stiffness of theory. Throughout his letters, Keats committed to paper various revolutionary philosophical concepts (“negative capability,” “the chameleon poet,” “the vale of soul-making,” “the mansion of many apartments,” “t-wang-dillo-dee”) as though they were trivial thoughts on the weather, and he did so in letters to friends, family members, lovers, and literary compatriots alike.

Negative capability, perhaps the most famous of these provisional concepts, has gained a life of its own, inspiring poets and fascinating scholars in the two hundred years since Keats mentioned it in passing in a letter to his brothers:

I had not a dispute but a disquisition with Dilke, upon various subjects; several things dovetailed in my mind, and at once it struck me what quality went to form a Man of Achievement, especially in Literature, and which Shakespeare possessed so enormously—I mean Negative Capability, that is, when a man is capable of being in uncertainties, mysteries, doubts, without any irritable reaching after fact and reason—Coleridge, for instance, would let go by a fine isolated verisimilitude caught from the Penetralium of mystery, from being incapable of remaining content with half-knowledge. This pursued through volumes would perhaps take us no further than this, that with a great poet the sense of Beauty overcomes every other consideration, or rather obliterates all consideration.

This is all Keats gave us.

“What is so striking about the famous ‘Negative Capability’ letter,” wrote Grant F. Scott, the editor of Keats’ selected letters, “is not so much the term itself, though it has generated hundreds of pages of commentary, as the casual way in which it emerges out of the quotidian detail of Keats’ life.” Maybe the fact that it emerged from the details of his life—and, in particular, from a private discussion—is indeed a manifestation of the concept itself. Maybe explaining it in more than a paragraph would have diminished its subtlety. Maybe rigor mortis sets in on an idea the moment it is placed in the coffin of an essay. Maybe an idea such as negative capability needs the uncertainty, mystery, doubt—the half-baked half-knowledge—of the epistolary form. Maybe the pell-mell nature of the letter, its undetermined future, its contentedness with ignorance, its admission of being only one piece of a larger conversation, means it is, as a form, one of movement and malleability, of ambiguity and ambivalence.

What separates the publication of these Kenner/Davenport letters from Selected Letters of John Keats, or those of Woolf or Wilde or Kafka, is that this book offers readers the back-and-forth, the conversation—not one side, but both. “I hold on to your letters,” Davenport told Kenner, “and the benefits on this side are scarcely subconscious. My education. We keep up (if I don’t endanger the centipede by asking him to explain the coordination of his podia) a conversation. I only hope I’m worth your effort.” Here we get the whole exchange, or as much of it as one could ever expect to be privy to. Therein lies the marvel of a book like this: it clearly reveals the letter for the philosophical form it is—a true dialogue.

The ping-ponging of correspondence, dialogic more than dialectic, never tries to achieve full knowledge or uniform consistency. “How discontinuous the world and this letter!” wrote Davenport. The epistolary form is content with stammering, with half-knowledge; letters don’t proffer the finality of winners and losers, for they are not the dictations of a formal debate. They are a more complicated, more nuanced version of Plato’s dialogues—messier, more inconsistent, and without resolution.

This is not the first text compiling the epistolary thrust and parry of a pair of intellectuals, of course. The letters of Conrad Aiken and Malcolm Lowry have been published together, as have those of Walter Benjamin and Theodor Adorno, Anaïs Nin and Henry Miller, and Hermann Hesse and Thomas Mann, among others.

While the benefit of a book like this is, to use the words of Davenport, “the advantage of two knowledges perceiving together,” the inevitable risk of this kind of back-and-forth collection is that we view the exchange at the pace of a book reader rather than the life-corrupted pace of a letter writer and letter receiver. “The exchange of letters,” Benjamin explained,

characteristically takes shape in the mind of posterity (whereas the single letter, in regard to its author, may lose something of its life): as letters are read consecutively with only the briefest intervals, they change objectively, from within their living selves.

In other words, a single letter has a momentary function that gets lost when read as a back-and-forth exchange. Time passes in the gaps between letters. Life happens between the licking of stamps. There is something a little voyeuristic, a little seedy, a little unfair, perhaps, in looking too closely at the nakedness of a moment without acknowledging the clothed gaps between those bare moments.

“Saving a letter is like trying to preserve a kiss,” claimed John Cheever, another great epistolarian.2 But saving a letter is not like trying to preserve a kiss; instead it is like holding on to a photograph of a kiss. In doing so, a person isn’t trying to preserve all the emotions, thoughts, and sensations that contributed to the moment, but merely holding on to a small piece of that moment, some token, some documentation, some remembrance. Countless scrapbooks are filled with this bric-a-brac.

“Your cards and letters are like messages from a world I might have imagined in a daydream,” Davenport admitted to Kenner. They tell a story, though always an incomplete one—fragmentary, labyrinthine, uncertain.

“Which is all of the story, like a torn papyrus,” Kenner wrote in “Ghosts and Benedictions,” the opening section of The Pound Era. “That is how the past exists, phantasmagoric weskits, stray words, random things recorded. The imagination augments, metabolizes, feeding on all it has to feed on, such scraps.”

1 There may be no writer since Herman Melville better than Kenner at crafting a strangely sublime simile. Elsewhere in The Pound Era, he wrote of words that “lie flat like the forms on a Cubist surface” and explained that “writing is largely quotation, quotation newly energized, as a cyclotron augments the energies of common particles circulating.” ↩

2 The homoerotic nature of some of his posthumously published correspondence became such a pop culture meme that there’s a Seinfeld episode titled “The Cheever Letters,” in which a character discovers that her father had a homosexual affair with the secretly bisexual writer. ↩