Without a decisive naval force, we can do nothing definitive, and with it, everything honorable and glorious.

—George Washington, 1781Liquid Eternity

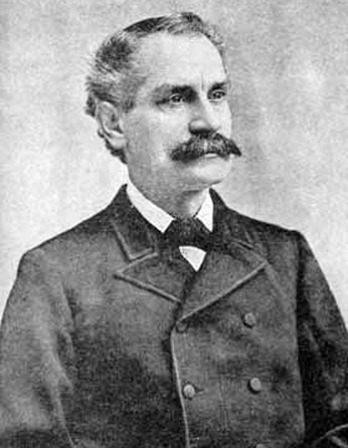

Lafcadio Hearn on the shore and the “infinite blue ghost” beyond.

The charm of a single summer day on these island shores is something impossible to express, never to be forgotten. Rarely in the paler zones do earth and heaven take such luminosity: those will best understand me who have seen the splendor of a West Indian sky.

And yet there is a tenderness of tint, a caress of color in these gulf days which is not of the Antilles—a spirituality, as of eternal tropical spring. It must have been to even such a sky that Xenophanes lifted up his eyes of old when he vowed the infinite blue was God—it was indeed under such a sky that Hernando de Soto named the vastest and grandest of southern havens Espiritu Santo—the Bay of the Holy Ghost. There is something unutterable in this bright gulf air that compels awe—something vital, something holy, something pantheistic—and reverentially the mind asks itself if what the eye beholds is not the pneuma indeed, the infinite breath, the divine ghost, the great blue soul of the unknown. All, all is blue in the calm—save the low land under your feet, which you almost forget, since it seems only as a tiny green flake afloat in the liquid eternity of day. Then slowly, caressingly, irresistibly, the witchery of the infinite grows upon you: out of time and space you begin to dream with open eyes—to drift into delicious oblivion of facts—to forget the past, the present, the substantial—to comprehend nothing but the existence of that infinite blue ghost as something into which you would wish to melt utterly away forever.

And this day magic of azure endures sometimes for months together. Cloudlessly the dawn reddens up through a violet east: there is no speck upon the blossoming of its mystical rose—unless it be the silhouette of some passing gull, whirling his sickle wings against the crimsoning. Ever, as the sun floats higher, the flood shifts its color. Sometimes smooth and gray yet flickering with the morning gold, it is the vision of John—the apocalyptic sea of glass mixed with fire—again, with the growing breeze, it takes that incredible purple tint familiar mostly to painters of West Indian scenery; once more, under the blaze of noon, it changes to a waste of broken emerald. With evening, the horizon assumes tints of inexpressible sweetness—pearl lights, opaline colors of milk and fire, and in the west are topaz glowings and wondrous flushings as of nacre. Then, if the sea sleeps, it dreams of all these—faintly, weirdly—shadowing them even to the verge of heaven.

The Raft of the Medusa, by Théodore Géricault, 1819. Louvre, Paris, France.

Beautiful, too, are those white phantasmagoria which at the approach of equinoctial days mark the coming of the winds. Over the rim of the sea a bright cloud gently pushes up its head. It rises, and others rise with it to right and left—slowly at first, then more swiftly. All are brilliantly white and flocculent. Gradually they mount in an enormous line high above the gulf, rolling and wreathing into an arch that expands and advances—bending from horizon to horizon. A clear, cold breath accompanies its coming. Reaching the zenith, it seems there to hang poised awhile—a ghostly bridge arching the empyrean—upreaching its measureless span from either underside of the world. Then the colossal phantom begins to turn, as on a pivot of air—always preserving its curvilinear symmetry but moving its unseen ends beyond and below the sky circle. And at last it floats away unbroken beyond the blue sweep of the world with a wind following after. Day after day, almost at the same hour, the white arc rises, wheels, and passes.

Never a glimpse of rock on these low shores—only long, sloping beaches and bars of smooth tawny sand. Sand and sea teem with vitality; over all the dunes there is a constant susurration, a blattering and swarming of crustaceans—through all the sea there is a ceaseless play of silver lightning, flashing of myriad fish. Sometimes the shallows are thickened with minute, transparent, crablike organisms, all colorless as gelatin. There are days also when countless medusas drift in—beautiful veined creatures that throb like hearts, with perpetual systole and diastole of their diaphanous envelopes: some, of translucent azure or rose, seem in the flood the shadows or ghosts of huge campanulate flowers; others have the semblance of strange living vegetables—great milky tubers, just beginning to sprout. But woe to the human skin grazed by those shadowy sproutings and spectral stamens! The touch of glowing iron is not more painful. Within an hour or two after their appearance, all these tremulous jellies vanish mysteriously as they came.

Perhaps, if a bold swimmer, you may venture out alone a long way—once! Not twice!—even in company. As the water deepens beneath you and you feel those ascending wave currents of coldness arising which bespeak profundity, you will also begin to feel innumerable touches, as of groping fingers—touches of the bodies of fish, innumerable fish fleeing toward shore. The farther you advance, the more thickly you will feel them come, and above you and around you, to right and left, others will leap and fall so swiftly as to daze the sight, like intercrossing fountain jets of fluid silver. The gulls fly lower about you, circling with sinister squeaking cries; perhaps for an instant your feet touch in the deep something heavy, swift, lithe, that rushes past with a swirling shock. Then the fear of the abyss, the vast and voiceless nightmare of the sea, will come upon you; the silent panic of all those opaline millions that flee glimmering by will enter into you also.

From what do they flee thus perpetually? Is it from the giant sawfish or the ravening shark? From the herds of the porpoises or from the tarpon—that splendid monster whom no net may hold—all helmed and armored in argent plate mail? Or from the hideous devil fish of the gulf—gigantic, flat bodied, black, with immense side fins ever outspread like the pinions of a bat—the terror of lugger men, the uprooter of anchors? From all these, perhaps, and from other monsters likewise—goblin shapes evolved by nature as destroyers, as equilibrists, as counterchecks to that prodigious fecundity, which, unhindered, would thicken the deep into one measureless and waveless ferment of being. But when there are many bathers, these perils are forgotten—numbers give courage—one can abandon oneself, without fear of the invisible, to the long, quivering, electrical caresses of the sea.

Lafcadio Hearn

From Chita. In 1887 Hearn published Some Chinese Ghosts and began writing a series of dispatches on the West Indies for Harper’s, living for a time on the island of Martinique. He accepted another assignment from the magazine in 1890 to go to Japan, where he hoped to capture a picture of “one taking part in the daily existence of the common people and thinking with their thoughts.” He never returned to the West, becoming a Japanese subject around 1895 and an English professor at the Imperial University of Tokyo in 1896.