To Mrs. Warren,

Although I have not yet written to you, be assured Madam, you have been the subject of some of my most pleasing thoughts. The sweet communion we have often had together and the pleasant hours I have passed both at Milton and Braintree I have not realized in Europe. I visit and am visited, but not being able to converse in the language of the country, I can only silently observe manners and men. I have been here so little while that it would be improper for me to pass sentence or form judgments of a people from a converse of so short duration. This I may, however, say with truth, that their manners are totally different from those of our own country. If you ask me what is the business of life here? I answer, pleasure. The beau monde, you reply. Ay, Madam, from the throne to the footstool it is the science of every being in Paris and its environs. It is a matter of great speculation to me when these people labor. I am persuaded the greater part of those who crowd the streets, the public walks, the theaters, the spectacles, as they term them, must subsist upon bread and water. In London the streets are also full of people, but their dress, their gait, every appearance indicates business—except on Sundays, when every person devotes the day, either at church or in walking, as is most agreeable to his fancy. But here, from the gaiety of the dress and the places they frequent, I judge pleasure is the business of life. We have no days with us in our country by which I can give you an idea of the Sabbath here, except commencement and election. Paris upon that day pours forth all her citizens into the environs for the purpose of recreation.

I believe this nation is the only one in the world which could make pleasure the business of life and yet retain such a relish for it as never to complain of its being tasteless or insipid; the Parisians seem to have exhausted nature and art in this science, and to be triste is a complaint of a most serious nature. In the family of Monsieur Grand, who is a Protestant, I have seen a decorum and decency of manners, a conjugal and family affection, which are rarely found, where separate apartments, separate pleasures and amusements show the world that nothing but the name is united. But while absolutions are held in estimation, and pleasure can be bought and sold, what restraint have mankind upon their appetites and passions? There are few of them left in a neighboring country amongst the beau monde, even where dispensations are not practiced. Which of the two countries can you form the most favorable opinion of, and which is the least pernicious to the morals? That where vice is licensed, or where it is suffered to walk at large soliciting the unwary and unguarded—as it is to a most astonishing height in the streets of London, and where virtuous females are frequently subject to insults. In Paris no such thing happens. The greatest decency and respect is shown by all orders to the female character. The stage is in London made use of as a vehicle to corrupt the morals. In Paris no such thing is permitted. They are too polite to wound the ear. In one country vice is like a ferocious beast, seeking whom it may devour; in the other like a subtle poison, secretly penetrating and working destruction. In one country you cannot travel a mile without danger to your person and property, yet public executions abound; in the other, your person and property are safe, executions are very rare—but in a lawful way, beware, for with whomsoever you have to deal, you may rely upon an attempt to overreach you. In the graces of motion and action this people shine unrivaled.

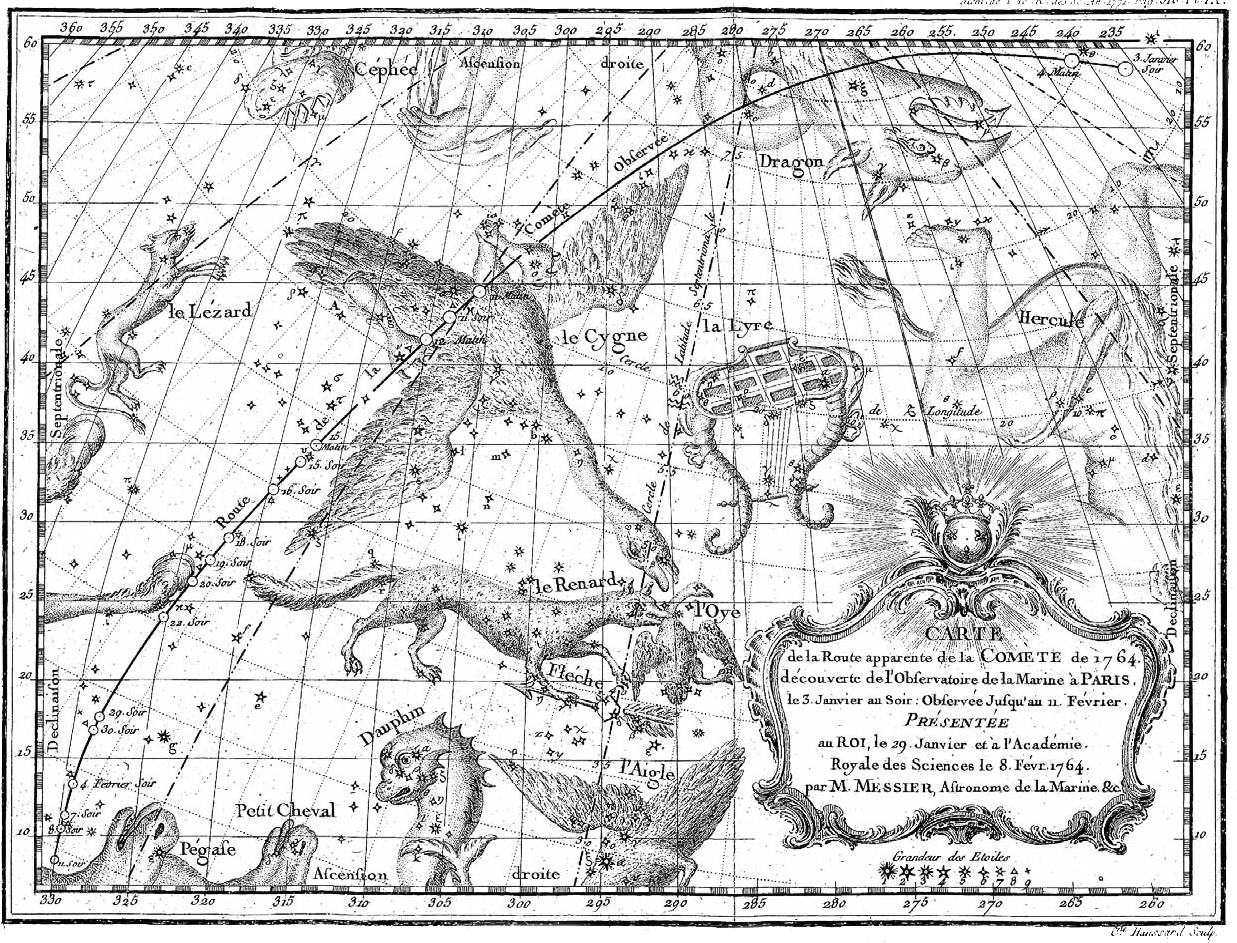

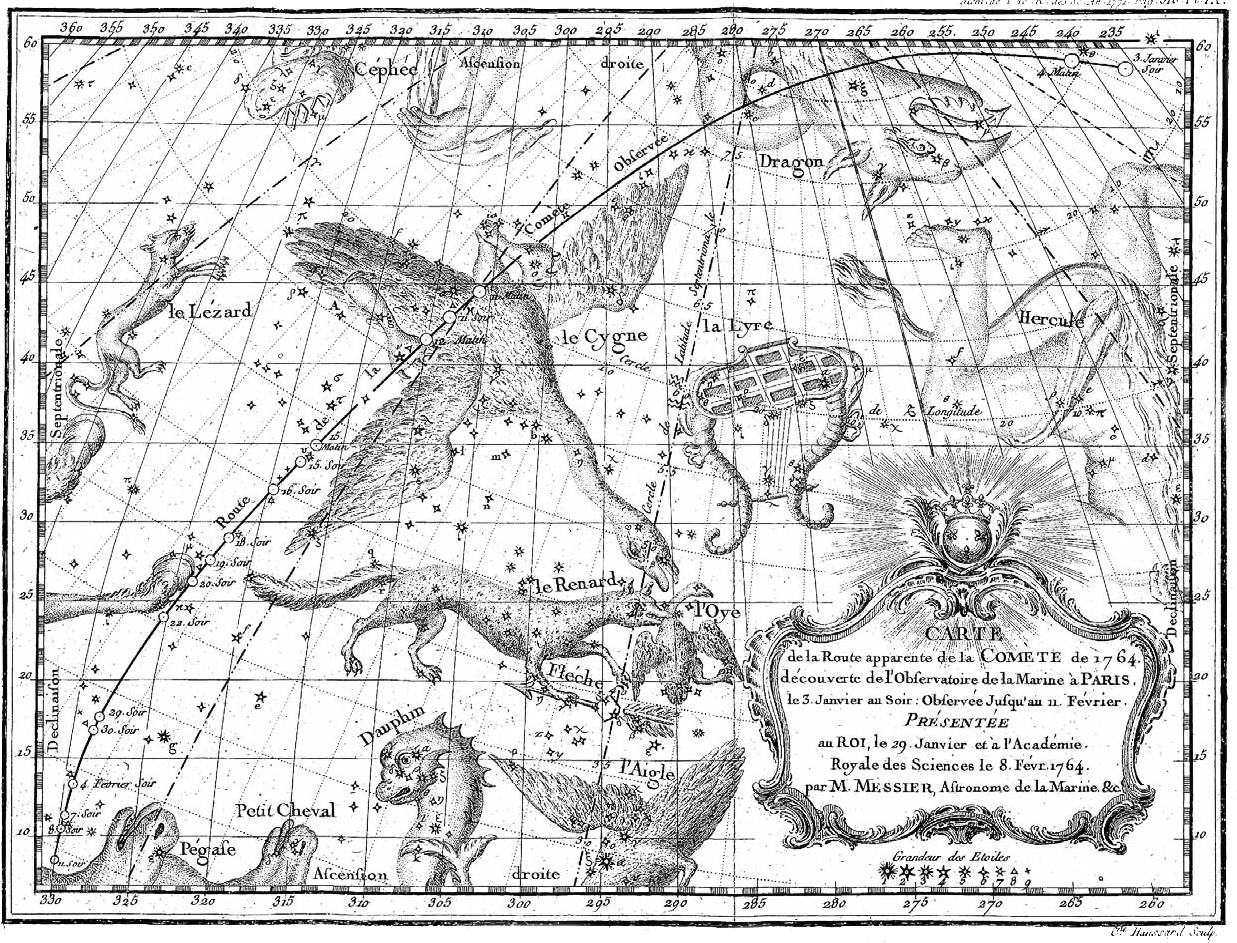

Star chart with the route of the 1764 comet, by Charles Messier, 1764.

The theaters exhibit to me the most pleasing amusement I have yet found. The little knowledge I have of the language enables me to judge here, and the actions, to quote an old phrase, speak louder than words. I was the other evening at what is called the French Theater (to distinguish it from several others), it being the only one upon which tragedies are acted. The dresses were superb, the house elegant and beautiful, the actors beyond the reach of my pen. To these public spectacles (and to every other amusement) you may go with perfect security to your person and property. Decency and good order are preserved, yet are they equally crowded with those of London; but in London, at going in and coming out of the theater, you find yourself in a mob and are every moment in danger of being robbed. In short, the term John Bull, which Swift formerly gave to the English nation, is still very applicable to their manners. The cleanliness of Britain, joined to the civility and politeness of France, could make a most agreeable assemblage. You will smile at my choice, but as I am likely to reside some time in this country, why should I not wish them the article in which they are most deficient?

It is the established custom of this country for strangers to make the first visit. Not speaking the language lays me under embarrassments. For to visit a lady merely to bow to her is painful, especially where they are so fond of conversing as the ladies here generally are, so that my female acquaintance is rather confined as yet, and my residence four miles from Paris will make it still more so.

This village of Auteuil is a very pretty summer retreat, but not so well calculated for winter. I fear it will prove as cold as Milton Hill. If I was to judge of the winters here by what I have experienced of the fall, I should think they were equally severe as with us. We begin already to find fires necessary.

I sigh (though not allowed) for my social tea parties which I left in America, and the friendship of my chosen few. Their agreeable converse would be a rich repast to me, could I transplant them round me in the village of Auteuil, with my habits, tastes, and sentiments, which are too firmly riveted to change with change of country or climate; and at my age, the greatest of my enjoyments consists in the reciprocation of friendship.

From a letter. Although not formally educated, Abigail Smith as a child made use of her father’s voluminous library and was tutored by her grandmother. In 1764 she married John Adams, who often availed himself of his wife’s keen political intelligence during his terms of public office, not only in America but also in France and England. She died at the age of seventy-three in 1818.

Back to Issue