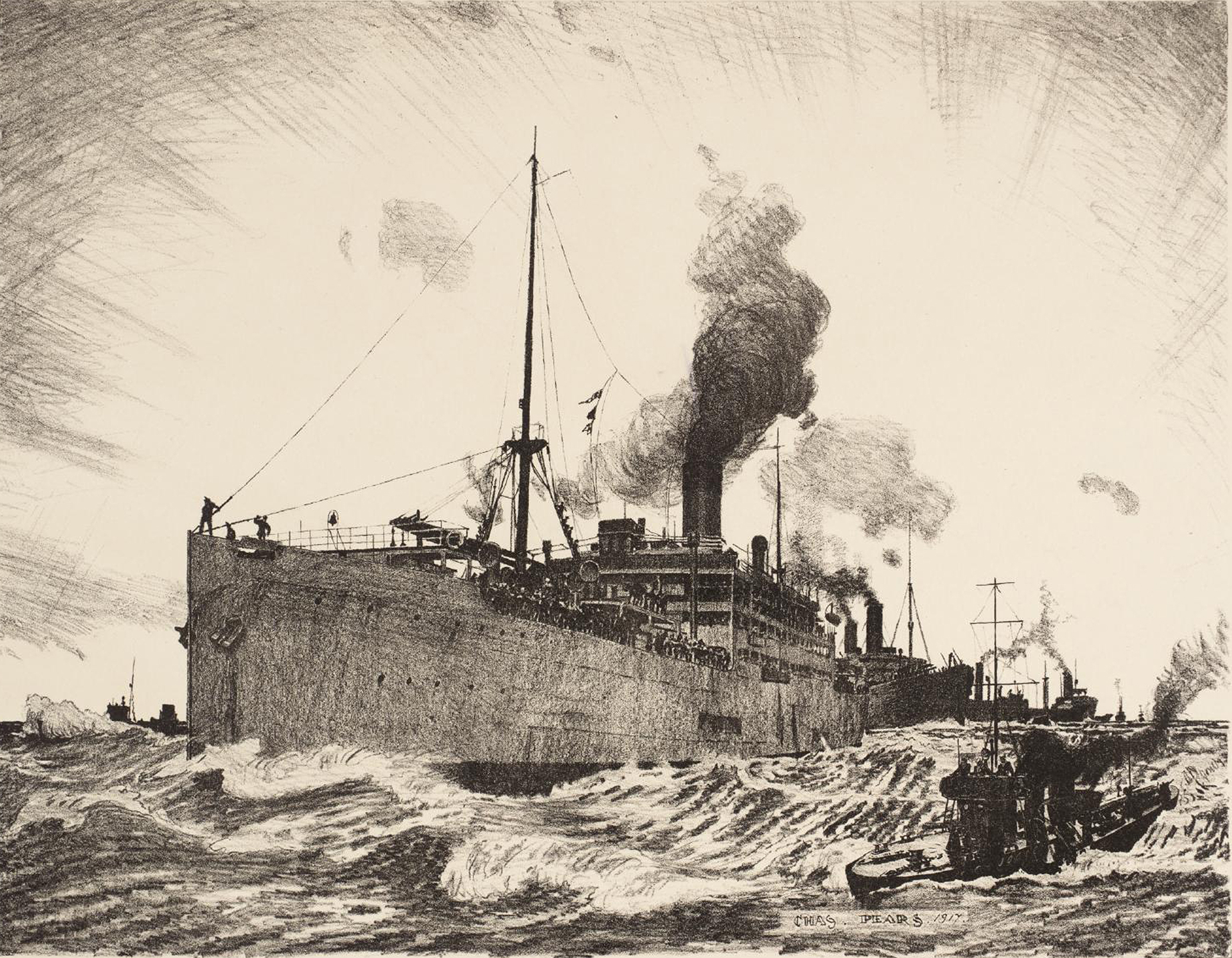

Transport by Sea: Transporting Troops, by Charles Pears, 1917. Photograph © Tate (CC-BY-NC-ND 3.0).

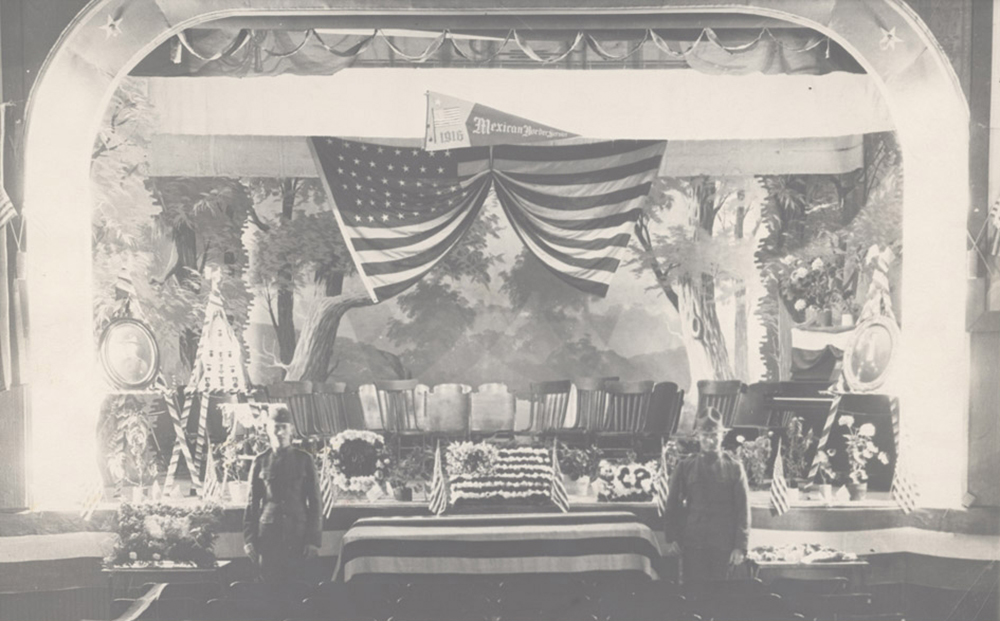

In her Pulitzer Prize–winning novel One of Ours (1922), Willa Cather fictionalized the story of her first cousin Grosvenor P. Cather, who had died in the World War I battle of Cantigny, France, in May 1918, along with 198 other U.S. troops. Grosvenor had a fascinatingly sensitive and rebellious temperament with which Cather felt a strong affinity. As she wrote in a letter to her aunt Frances Smith Cather, Grosvenor’s mother, on June 12, 1918, a few weeks after his death, “He was restless on a farm; perhaps he was born to throw all his energy into this crisis and to die among the first and bravest of his country.”

Cather’s primary objective in the novel, as described by her companion, Edith Lewis, had not been to write about the war. She sought instead to precisely re-create and describe her cousin’s figure and personality through the character of Claude Wheeler (a name that significantly reverses Cather’s own initials). In telling the story of this young, perceptive, and curious boy who pursued a university education only to have to go back to farming to continue the family business and get trapped in an unhappy marriage, Cather wanted to show Claude’s inner, desperate search for a purpose:

He was twenty-one years old, and he had no skill, no training—no ability that would ever take him among the kind of people he admired. He was a clumsy, awkward farmer boy, and even Mrs. Erlich seemed to think the farm the best place for him. Probably it was; but all the same he didn’t find this kind of life worth the trouble of getting up every morning. He could not see the use of working for money, when money brought nothing one wanted. Mrs. Erlich said it brought security. Sometimes he thought this security was what was the matter with everybody; that only perfect safety was required to kill all the best qualities in people and develop the mean ones. Ernest, too, said “it’s the best life in the world, Claude.” But if you went to bed defeated every night, and dreaded to wake in the morning, then clearly it was too good a life for you. To be assured, at his age, of three meals a day and plenty of sleep, was like being assured of a decent burial. Safety, security; if you followed that reasoning out, then the unborn, those who would never be born, were the safest of all; nothing could happen to them.

The book is centered around Claude’s gradual escape from his unhappiness and frustration and his growing conviction that indeed “there was something splendid about life, if he could but find it!”1—a hunt that progressively, and ironically enough, brings him to enlist in the war.

Critics and Cather scholars have long debated the value of One of Ours, often arguing that it lacks the innovative refinement of other Cather works such as My Àntonia and A Lost Lady, among others. Some have complained about the novel’s overtly patriotic remarks, missing the fact that Cather used them solely to mimetically illustrate Claude’s blind desire to go to war. But recently the novel has been reevaluated for its modernist depiction of psychological complexities. Cather created a character who believed his inner, idealized embrace of the war was the perfect solution to his unsatisfactory life in the Midwest. Yet the section of the book that focuses on the 1918 flu pandemic is shot through with a vein of irony that crucially illuminates the naivete of Claude’s perspective.

As Cather wove her cousin’s life into her novel, she also drew in threads from an event happening concurrently with the war: the spread of the Spanish flu. Throughout her life the writer remained strongly curious about—and scared of—illnesses, and she had deeply researched the 1918 appearance of influenza. The choice to write about the flu is a trait that makes her stand out among her contemporaries, a majority of whom did not seem to have an interest in the subject and did not discuss the flu pandemic in their books.2

She had investigated the pandemic’s tragic consequences among troops and how it interacted with war operations; while war deaths amounted to around 20 million over the course of the Great War, flu deaths during the pandemic totaled around 50 million. Cather was aware that, as observed by scholar Susan Kent, “the conditions of this war may well have enabled a common and usually mild disease to mutate into a deadly strain that spread like wildfire around the world…Environments with large concentrations of people enabled the virus to take hold [and] sufficient hosts—young, healthy men—were continuously made available, so that the virus could survive to reproduce.” Soldiers were perfect carriers for the infection—Kent explained, “In attacking the virus,…the cytokines also attacked vulnerable respiratory tissue, making those possessing the strongest immune systems the most likely to succumb to respiratory illness, particularly pneumonia.”

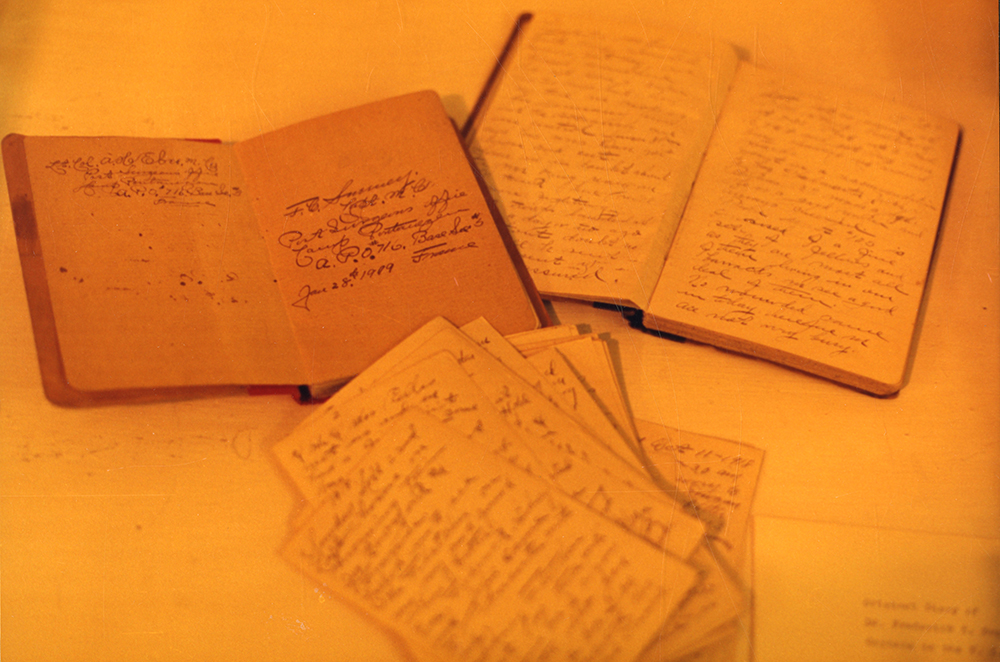

Cather not only read the alarming reports of the spread of the epidemic among soldiers from newspapers, she also was able to rely on the invaluable firsthand testimony of Dr. Frederick Sweeney, who had treated Cather for the flu in the fall of 1919 while she wrote One of Ours. Sweeney had been a medical officer on a troop ship headed for France and had kept a diary to record the experience. Cather asked to read it, and he consented, if reluctantly. From the diary, she extracted many technical details, settings, and emotional notes she could use in her book: the image of bleeding to death from the nose, the description of the illness’ evolution into pneumonia, the scene of a bottom hold full of sweat and stench, and the burials at sea of the soldiers who died.

Sweeney wrote, “It seems brutal to put a crowd of men on board a ship like this without proper medical supplies to care for them in case of illness…I knew the trip overseas was a long one, but that we should have such a sickly and dangerous trip never entered my mind.”3 Such passages must have had a strong, inflaming impact on the creative mind of Cather. Readers can see Cather’s absorption of these horrors in book 4 of One of Ours. “The Voyage of the Anchises” follows Claude’s trip to Europe by sea. A few days after the ship’s departure, an outbreak of sickness materializes, a scourge of influenza that rapidly kills many soldiers. Claude is spared. He serves as a nurse and a comforting presence for his sick colleagues. His confidence in the meaning of the military enterprise remains strong, notwithstanding the tragic deaths and burial at sea of his companions. Meanwhile, the narrator behind the scenes continues to insist on the blunt absurdity and meaninglessness of the event, with scenes and dialogue that strongly highlight the horrifying nature of having influenza on board a troop ship.

In book 4, the setting shifts from the United States to an old English boat on its way to the front. The name that Cather gives to the boat, the Anchises, closely echoes the name of the real English boat on which Dr. Sweeney sailed to Europe, the Ascanius. In Greco-Roman mythology, Ascanius is the son of Aeneas, while Anchises is Aeneas’ father. This shift in the lineage of the naming may signify a precise symbolic intention for Cather. Ascanius represents the continuation and prosperity of Aeneas’ future generations; Anchises significantly embodies a function of prediction and foretelling. Anchises in fact predicted that the new land where Aeneas’ descendants would found a new civilization was Italy. He repeatedly appeared in Aeneas’ dreams with prophecies and omens. The boat that shares Anchises’ name in One of Ours predicts and foreshadows the random violence and meaninglessness of the war it has charted a course toward. In the concentrated space of the boat and of the small cabins, young soldiers, excited and proud of entering the war enterprise, start to fall ill with a disease that was capable of damaging young people with a strong immune system more than anybody else. One after another they die longing for home and are buried at sea as if they were “merely waste in a great enterprise, thrown overboard like rotten ropes.”

One of Ours is a book that repeatedly asks, through its main character’s existential reflections, about the true worth and value of life. Antonia S. Byatt sees this concept as a crucial component of all Cather’s writing; as she puts it, Cather had a “stoic yet fierce interest in the primitive matter of human energy over a whole life.” This wasted energy, consumed and overcome by a mysterious and powerful epidemic and thrown into the sea, becomes an omen of sheer lack of meaning. Even Claude—who still remains stubbornly convinced that the war is a great endeavour and that, notwithstanding others’ deaths, “he and the boat went on, and always on”—asks himself, while thinking of his dead companions, just minutes before reaching France, “How long would their bodies toss […] in that inhuman kingdom of darkness and unrest?” Cather’s depiction of the absurdity and ultimate tragedy of these deaths by the flu is strikingly different from the deaths she describes in heroic terms in later sections of the book, when soldiers die on the battlefields.

The story of the death on board of Claude’s corporal, a placid, good-natured German American boy called Fritz Tannhauser (also called Big Tannhauser), encapsulates Cather’s approach to describing such a tragic development.

Big Tannhauser’s fever had left him, but so had everything else. He lay in a stupor. His congested eyeballs were rolled back in his head and only the yellowish whites were visible. His mouth was open and his tongue hung out at one side. From the end of the corridor Claude had heard the frightful sounds that came from his throat, sounds like violent vomiting, or the choking rattle of a man in strangulation—and indeed, he was being strangled […] “Mein’arme Mutter!” he whispered distinctly. A few moments later he died in perfect dignity, not struggling under torture, but consciously, it seemed to Claude, like a brave boy giving back what was not his to keep […] Corporal Tannhauser, along with four others, was buried at sunrise. No band this time; the chaplain was ill, so one of the young captains read the service. Claude stood by watching until the sailors shot one sack, longer by half a foot than the other four, into a lead-colored chasm in the sea. There was not even a splash […] The Army regulations minutely defined what was to be done with a deceased soldier’s effects. His uniform, shoes, blankets, arms, personal baggage, were all disposed of according to instructions. But in each case there was a residue; the dead man’s toothbrushes, his razors, and the photographs he carried upon his person. There they were in five pathetic little heaps; what should be done with them? Claude took up the photographs that had belonged to his corporal; one was a fat, foolish-looking girl in a white dress that was too tight for her, a little flag pinned on her plump bosom. The other was an old woman, seated, her hands crossed in her lap […] “I’ll take these,” he said. “And the others—just pitch them over, don’t you think?”

Starting from a detailed description of the physical symptoms exposing the brutal nature of influenza, Cather moves here to select a few elements (the words in German, the lack of a splash when the dead body is thrown at sea, the retrieving of the soldier’s effects and the pictures) capable of unleashing in readers a stark sense of pity and sadness and of pure wondering. While Claude will go on and die on the battlefield, blindly satisfying his almost delirious desire for a heroic task, in this section of the book Cather puts the naked truth in front of us, provoking us to ask how it can happen that a random virus like influenza can disrupt such a “heroic” plan. The role assigned to the flu by Cather in One of Ours was missed by contemporary reviewers—perhaps because the few pages were dedicated to it in comparison to the larger number portraying the war, or perhaps because the book was too close in time to the event itself. But it also was not recognized by the majority of later critics, who concentrated on condemning any rhetoric of patriotic sacrifice, even when this rhetoric was re-created with the sole purpose of representing its origins and effects in the mind of a young, idealistic boy, as Cather had done.

Influenza must instead be recognized in One of Ours as an ultimate intervention, an unpredictable factor that reverses plans and disrupts missions by dismantling these young boys’ assumed role in the war scheme: “So many [soldiers] who had set out with [Claude] were never to have any life at all, or even a soldier’s death.” As Cather had shown Claude’s growing enthusiasm, his meaning-making urge in going to the war, her tragic and theatrical display of influenza on board served to show the other side of the coin. Death by influenza was the ominous reminder of absurdity and nonsense in the already absurd and nonsensical reality of war.

1 All quotes from the novel, which was first published by Alfred A. Knopf in 1922, are taken from the text made available (and correspondent to Knopf’s first edition) in the Willa Cather Archive. ↩

2 Famous exceptions to this are Thomas Wolfe’s Look Homeward, Angel (1929), William Maxwell’s They Came Like Swallows (1937), and Katherine Anne Porter’s Pale Horse, Pale Rider (1939). ↩

3 Dr. Sweeney’s original diary belongs to the Jaffrey-Gilmore Foundation, but I was able to consult one of the few existing typewritten copies at the Love Library-Archives & Special Collections at the University of Nebraska–Lincoln. The picture reproduced above was taken from the original diary at the Jaffrey-Gilmore Foundation and was included in the typewritten copy I consulted. ↩