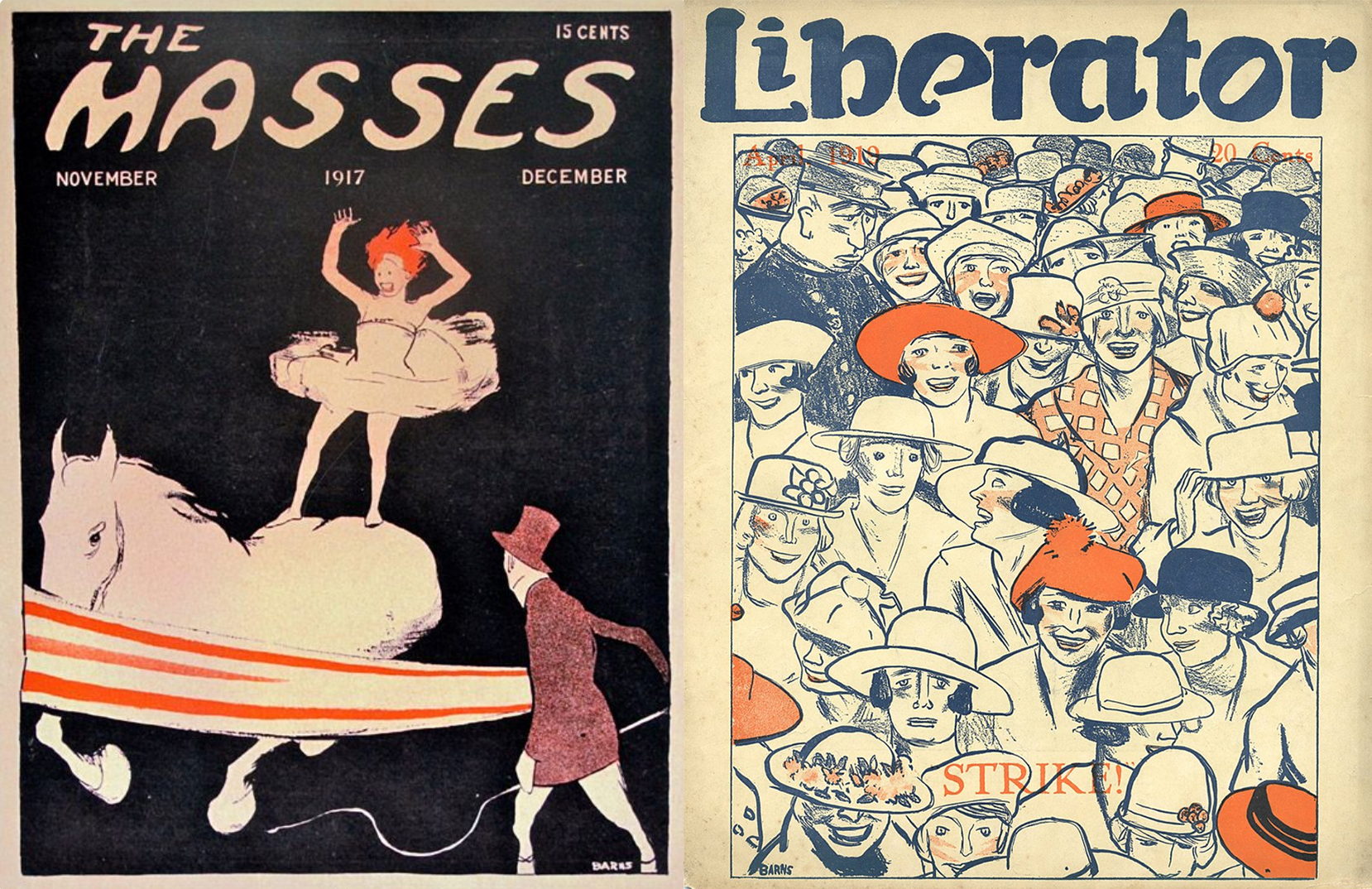

Two cover illustrations by Cornelia Barns: “Untitled (Circus Scene),” The Masses, November–December 1918; “Strike,” The Liberator, April 1919.

In 1911 Piet Mondrian, having not yet established his own lines and image-making, moved from Holland to Paris, where he made a living painting and selling copies of works he had seen at the Louvre. Ronald Reagan was born that year. It was the year of the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire, in which New York City garment workers, mostly women and girls, hurled themselves out of windows to their deaths in an attempt to escape the flames. And, in 1911, the first issue of The Masses hit the newsstands.

The Masses, which described itself as “a monthly magazine devoted to the interests of the working people,” was founded by Dutch socialist Piet Vlag, who was interested in providing a platform for art, writing, politics, and socialism in a fresh way to a large audience. Finding the undertaking either too challenging or not compelling enough, Vlag abandoned the project after only a few months, leaving it in the hands of the editorial board of writers, artists, and activists he had assembled. The group included journalist Inez Haynes Gillmore, cartoonist Art Young, and the painters George Bellows and John Sloane. A young artist named Cornelia Barns would soon join them.

Most competing socialist-sympathizing magazines of the time did not have the financial means to publish artwork, an advantage that would help elevate The Masses and give it a vital role in shaping a visual critique of political and social issues. But first the collective artists needed to find an editor to replace Vlag. They settled on Max Eastman, who was at the time teaching philosophy at Columbia University. They informed Eastman of their decision by sending him a telegram that read:

You are elected editor of THE MASSES. No pay!

Eastman accepted the position with energy and enthusiasm. His first undertaking was to write a manifesto.

This magazine is owned and published cooperatively by its editors. It has no dividends to pay, and nobody is trying to make money out of it. A revolutionary and not a reform magazine; a magazine with a sense of humor and no respect for the respectable; frank; arrogant; impertinent; searching for the true causes; a magazine directed against rigidity and dogma wherever it is found; printing what is too naked or true for a money-making press; a magazine whose final policy is to do as it pleases and conciliate nobody, not even its readers. There is a field for this publication in America. Help us find it.

In 1913 Richard Nixon was born. The Sixteenth Amendment was ratified, allowing Congress to levy income taxes without previous limitations. It was the year that Harriet Tubman died and Woodrow Wilson was inaugurated as twenty-eighth president of the United States. And in 1913 Eastman met and hired Cornelia Barns, a suffragette and illustrator. He later wrote:

Cornelia Barns possessed an instinct for the comic in pictorial art that few American artists have ever surpassed. She was a gentle brown-eyed girl with soft hair sleeked down around a comely and quiet face. She had no ambition or aggression in her nature, and came through the open door of The Masses like a child into a playroom, moved only by her liking for what she saw there. When its door closed she disappeared from fame as quietly as she had entered upon it—I don’t know why.

Eastman’s assessment of Barns may have been too dismissive—though young, she was already an accomplished artist when she arrived at the offices of The Masses. Barns was born in Flushing, New York, in 1888 to Mabel Balston Barns and Charles Edward Barns, a journalist and theater director who exposed his observant daughter to both politics and the arts. She attended the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, where she became associated with Robert Henri and his Ashcan School, an artistic movement concerned with illustrating the everyday lives of working-class people via rough lines and crude contours, in contrast to the more refined artistic approach that dominated the period. It was then, while a student, that Barns was awarded a travel grant to visit Europe in 1910. During her time at The Masses she was responsible for some of its most affecting illustrations, satires, and cover art. Her drawings gave visibility to issues such as women’s suffrage, child labor, male dominance, and birth control.

Of contributing editors at The Masses, Barns was in the minority who were actual members of the Socialist Party. One of the few female socialist artists contributing visual critiques for a wide audience to consume, she was able to offer a different perspective than that of her male counterparts. She made a point of turning her talents and attentions toward women’s suffrage, an issue that male socialists frequently dismissed. As the suffrage movement gained attention, so did disagreements as to how much the socialist movement should or shouldn’t align with the enfranchisement of women. A common socialist critique of women’s suffrage was that it presented an agenda of reform rather than revolt. If suffragists aimed to afford the female proletariat a place in the political landscape, how could they also seek to overthrow that system? In 1919 The Suffragist Magazine ran a cover illustration by Barns called “Waiting” that showed just that: women waiting, implacable in their defiance, for their rights.

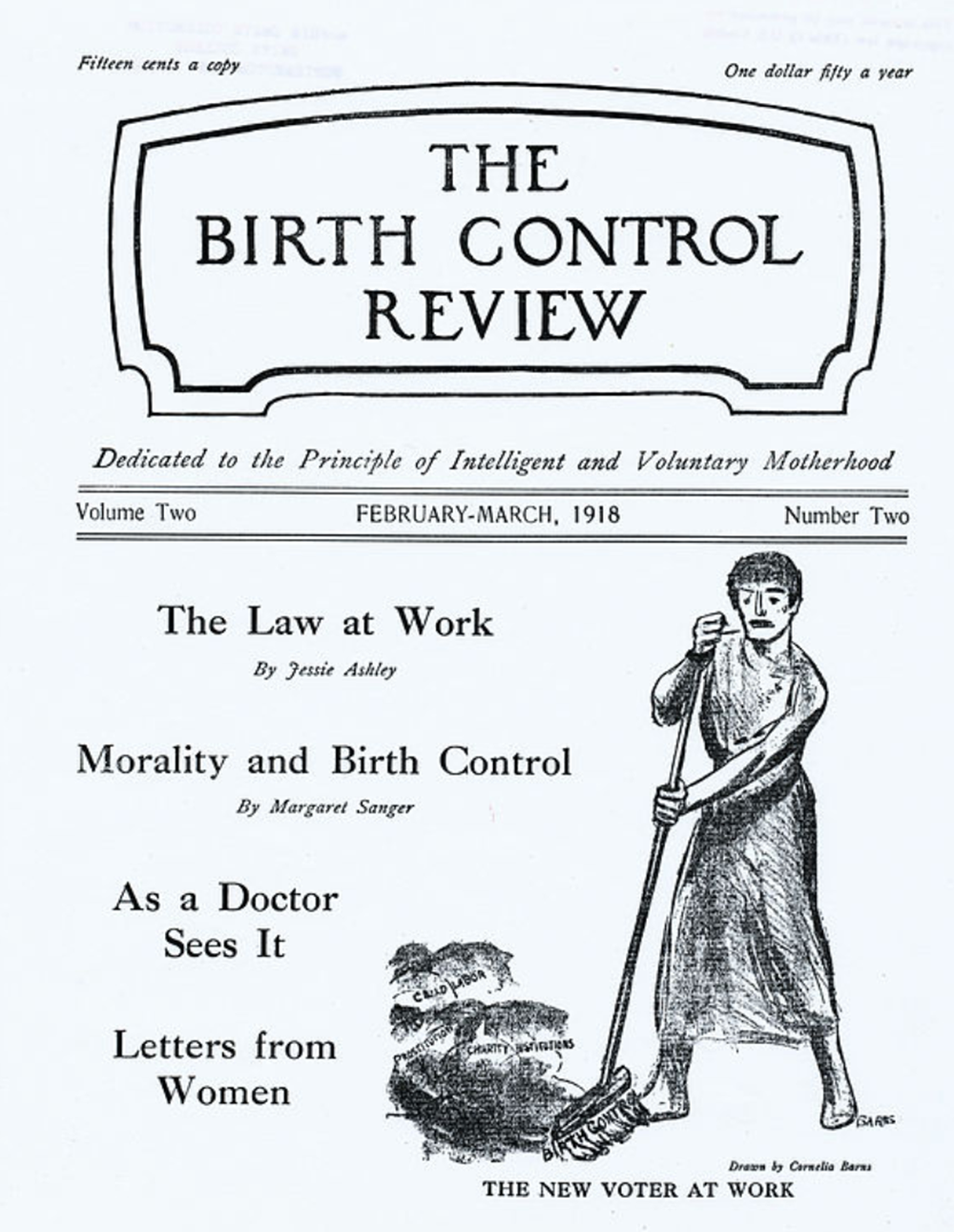

Many of Barns’ drawings illustrate issues of class and gender and how the two intersect. Her 1918 cover “The New Voter at Work” for The Birth Control Review, a magazine published by Margaret Sanger, depicted a workingwoman sweeping up the words child labor, prostitution, and charity institutions along with dust and garbage. Also for The Birth Control Review she drew “We Accuse Society”: a pregnant woman with her five children and hapless husband confronting the court system, addressing the importance of family planning and legal access to information regarding it.

Adept at illustrating pretentiousness along with white-male dominance and the roles both play in subjugating the rest of society, Barns oscillated between using minimal or no captions while making her position clear and changing how we understand a drawing based entirely on its caption.

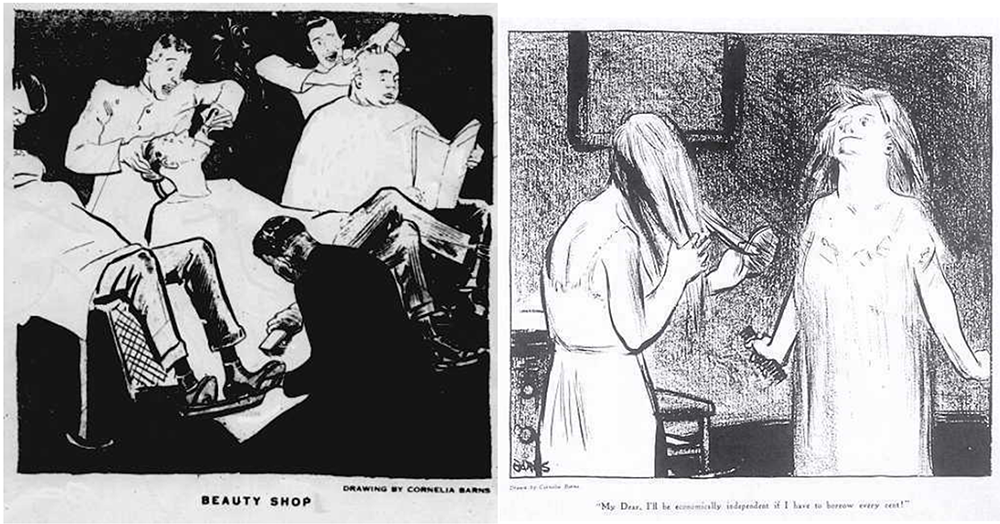

“United We Stand: Anti-Suffrage Meeting,” a 1914 illustration she did for The Masses, shows four well-dressed men, smoking and looking alternately bored, pompous, dismissive, and condescending. In “Twelve-Thirty,” she draws a proletariat woman, her back to us, having a cup of coffee at what appears to be the end of a long shift. The illustration simply titled “Beauty Shop” depicts a line of men having their shoes shined and heads shaved.

Her illustration of two women brushing their hair is given a surprising meaning with the caption “My dear, I’ll be economically independent if I have to borrow every cent!” Her seemingly innocuous drawing of a couple on a park bench gets the caption “Submarines Notwithstanding”—a reference to the world war under way.

Barns often used bold lines, limited color palettes, and strong graphic shapes. For the November–December 1917 issue of The Masses, she employed all three in her cover illustration “Untitled (Circus Scene).” Barns portrays a woman balancing on the back of a circus horse, flame hair licking out from her head in all directions as if attempting to escape whatever she approaches, arms flailing, an expression of surprise, shock, and fear frozen on her face—all under the command of the circus ringmaster, a man holding a menacing crop, elbow half crooked as he readies to use it. (The etymology of the idiom hair on fire can be traced back to early Buddhism: “a person should seek enlightenment in the same way a person whose ‘hair is on fire’ would seek water…with the utmost urgency.”) The ringmaster wears a top hat and overcoat and turns his back to us, focusing his energy on the woman in the ring and controlling all that happens. He is separated from her by only a sash. So perilous is her position that it quickens the heartbeat to look at it.

In 1917 the Bolshevik revolution brought an end to the Romanov dynasty. Vladimir Lenin led the Bolsheviks in overthrowing the Duma and installing a new government under his rule. Under his command, the Red Army entered civil war. That year Germany engaged in submarine warfare and severed diplomatic relations with the U.S. And in 1917 Congress passed the Espionage Act, which would come to play an important role in the dissolution of The Masses.

By the end of 1917 The Masses was forced to shut down. Barns’ “Untitled (Circus Scene)” appeared in the last issue. Any magazine distributed through the U.S. postal system, an agency of the U.S. government, had to comply with the newly passed Espionage Act:

Whoever, when the United States is at war, shall wilfully make or convey false reports or false statements with intent to interfere with the operation or success of the military or naval forces of the United States or to promote the success of its enemies and whoever when the United States is at war, shall wilfully cause or attempt to cause insubordination, disloyalty, mutiny, refusal of duty, in the military or naval forces of the United States, or shall wilfully obstruct the recruiting or enlistment service of the United States, to the injury of the service or of the United States, shall be punished by a fine of not more than $10,000 or imprisonment for not more than twenty years, or both.

The Masses had taken a strong antiwar stance; Albert Burleson, the postmaster general, and Thomas Patten, the New York postmaster, lost no time citing the Espionage Act as a reason to refuse mail service to radical magazines. In its defense, The Masses claimed that a critique of the government did not equal treason and that suppression of the magazine’s content violated free speech. Judge Learned Hand agreed with the magazine, and the government immediately appealed his decision. Judge Charles M. Hough ordered a stay of proceedings, which stated that the August 1917 issue of the magazine be kept out of circulation until the court could evaluate its contents in November. When The Masses had the September issue ready, the postmaster revoked its mailing rights, arguing that it no longer qualified as a monthly magazine because it had skipped an issue. Despite this obvious attempt to hobble The Masses, the appeal of Hand’s decision was successful and the initial judgment overturned. By November the postmaster had effectively won: without access to circulation via mail, The Masses could not afford to stay in business and was forced to fold.

A year later, after the downfall of The Masses, Eastman and his sister Crystal started a new magazine called The Liberator. And—despite Eastman’s claims that she “disappeared”—Cornelia Barns continued to work after The Masses shut down, contributing to numerous other radical publications, including Eastman’s new venture, which took up many of the same political and social issues as The Masses.

Barns died of tuberculosis in 1941, at the age of fifty-three. Much of her work was destroyed in a flood at her home. Her lithographs, with their direct realist approach to social and political issues, their humor, and their gestural lines helped shape the avant-garde and give voice to women and workers who had none.