Atlanta must not lead the South to dream of material prosperity as the touchstone of all success. Already the fatal might of this idea is beginning to spread; it is replacing the finer type of Southerner with vulgar money-getters; it is burying the sweeter beauties of Southern life beneath pretence and ostentation. For every social ill, the panacea of wealth has been urged—wealth to overthrow the remains of the slave feudalism; wealth to raise the “cracker” Third Estate; wealth to employ the black serfs, and the prospect of wealth to keep them working; wealth as the end and aim of politics, and as the legal tender for law and order; and, finally, instead of truth, beauty, and goodness, wealth as the ideal of the public school.

Not only is this true in the world which Atlanta typifies, but it is threatening to be true of a world beneath and beyond that world—the black world beyond the veil. Today it makes little difference to Atlanta, to the South, what the Negro thinks or dreams or wills. In the soul-life of the land, he is today, and naturally will long remain, unthought of, half-forgotten; and yet when he does come to think and will and do for himself—and let no man dream that day will never come—then the part he plays will not be one of sudden learning, but words and thoughts he has been taught to lisp in his race childhood. Today, the ferment of his striving toward self-realization is to the strife of the white world like a wheel within a wheel: beyond the veil are smaller but like problems of ideals, of leaders and the led, of serfdom, of poverty, of order and subordination, and, through all, the veil of race. Few know of these problems; few who know notice them; and yet there they are, awaiting student, artist, and seer—a field for somebody sometime to discover. Hither has the temptation of Hippomenes penetrated; already in this smaller world, which now indirectly and anon directly must influence the larger for good or ill, the habit is forming of interpreting the world in dollars. The old leaders of Negro opinion, in the little groups where there is a Negro social consciousness, are being replaced by new; neither the black preacher nor the black teacher leads as he did two decades ago. Into their places are pushing the farmers and gardeners, the well-paid porters and artisans, the businessmen—all those with property and money. And with all this change, so curiously parallel to that of the other world, goes too the same inevitable change in ideals. The South laments today the slow, steady disappearance of a certain type of Negro—the faithful, courteous slave of other days with his incorruptible honesty and dignified humility. He is passing away just as surely as the old type of Southern gentleman is passing, and from not dissimilar causes—the sudden transformation of a fair far off ideal of freedom into the hard reality of breadwinning and the consequent deification of bread.

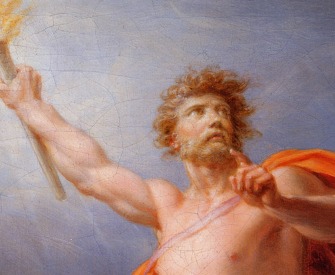

In the black world, the preacher and teacher embodied once the ideals of this people—the strife for another and a juster world, the vague dream of righteousness, the mystery of knowing; but today the danger is that these ideals, with their simple beauty and weird inspiration, will suddenly sink to a question of cash and a lust for gold. Here stands this black young Atalanta, girding herself for the race that must be run; and if her eyes be still toward the hills and sky as in the days of old, then we may look for noble running; but what if some ruthless or wily or even thoughtless Hippomenes lay golden apples before her? What if the Negro people be wooed from a strife for righteousness, from a love of knowing, to regard dollars as the be-all and end-all of life? What if to the mammonism of America be added the rising mammonism of the reborn South, and the mammonism of this South be reinforced by the budding mammonism of its half-awakened black millions? Whither, then, is the new world quest of goodness and beauty and truth gone glimmering? Must this and that fair flower of freedom which, despite the jeers of latter-day striplings, sprung from our fathers’ blood, must that too degenerate into a dusty quest of gold—into lawless lust with Hippomenes?

W.E.B. Du Bois studied with William James at Harvard University, receiving his PhD in 1895 and publishing his dissertation, “The Suppression of the African Slave Trade to the United States of America,” the following year. Helping to form the NAACP in 1909, he became the organization’s director of research and the founding editor of its magazine, The Crisis, where he served for twenty-four years, publishing the writing of, among others, Langston Hughes, Jean Toomer, and Countee Cullen. He became a consultant to the UN founding convention in 1945. A committed socialist, he was arrested in 1951 on suspicion of being a foreign-government agent. From 1952 to 1958, the State Department held his passport; he immigrated to Ghana in 1961 at the behest of its president.

Back to Issue