Everyone should know nowadays the unimportance of the photographic in art—that truth, life, or reality is an organic thing which the poetic imagination can represent or suggest, in essence, only through transformation, through changing into other forms than those which were merely present in appearance.

—Tennessee Williams, 1944The Sacred Word

By beautifying the word of God, the medium and the message became interconnected.

By Sabiha Al Khemir

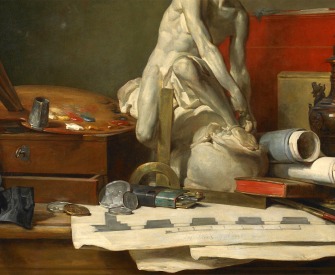

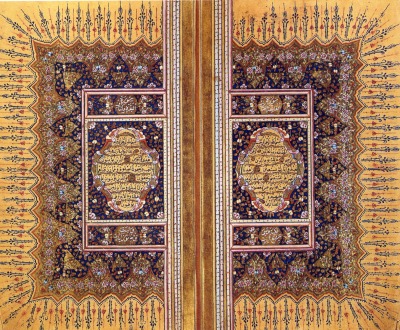

Qurʾan Manuscript, non-illustrated, dated 1268 AH/1851–52 AD. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, gift of Elizabeth M. Riley, 1980.

When the question of religious imagery in Islamic art made newspaper headlines in 2005 as a result of the Danish cartoons portraying the Prophet Muhammad, much of the accompanying discussion missed the point. While the Qur’an objects to idolatry, it does not forbid the use of figurative representations in secular settings. More than representation, what prompted the furor among some Muslims was the lack of respect in the medium of cartoon, by its nature a tool of distortion. Figurative imagery appears in the art of Sunni Turkey as well as the art of Shia Iran. The arts of the Muslim world in all media—painting, ceramics, glass, metalwork, carpets and textiles, ivory, stone, and woodcarvings—objects which throughout the centuries were part of secular spaces, are decorated with images of animal and human figures.

If Islam enforced the radical elimination of religious images, the Muslim rulers of Egypt would have destroyed the pharaonic sculptures (such as those still standing in Luxor Temple) as long ago as the seventh century. That they did not, and that these sculptures continue to stand separate from Muslim spaces of worship, speaks to the misunderstandings of Islamic art that still cloud the lines of sight in the Christian West.

I was reminded of that confusion when an old box of Islamic art books arrived from storage, having sat untouched for more than a decade in South London. Among them was a bundle of twenty multicolored notepads I’d kept during various research trips—a different hue for each journey. The purple pad was filled with notes from a trip taken to Egypt for my doctoral thesis on Fatimid imagery. The handwriting bordered on the undecipherable.

Thursday, April 2, 1987. I had struggled to keep a steady hand while writing, jolted in the back seat of a car, and as I left Cairo, heading toward the western desert, my Muslim driver had asked, “Why are you going to a Coptic monastery if you’re researching Islamic art?”

“I’m looking for comparative material.”

“Comparative material?” I caught his look in the rearview mirror.

“Yes. Coptic woodcarvings which are similar to Muslim woodcarvings.”

The driver said nothing after that. For the rest of the long drive to the monasteries of Wadi Natrun, I wrote comments on my visit to the Islamic Art Museum the day before. “The doors from the medieval Cairo Palace of the Fatimid Princess Sitt al-Mulk decorated with designs, filled with scenes of dancers, musicians, and seated monarchs, all carved in relief in the same style as wainscots that once ran around the reception hall.”

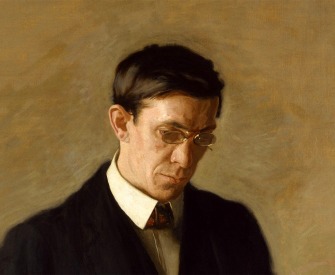

The Shades of Francesca da Rimini and Paolo Malatesta Appear to Dante and Virgil, by Ary Scheffer, 1855. Louvre Museum, Paris, France.

Friday, April 3, 1987. The entry was again written with a shaky hand, this time on the drive back from the monasteries. A monk with a majestic beard had showed me around, pointing at the carved woodwork in the churches. I was surprised by the obvious Coptic connection to the Islamic material. “Well,” the monk said, “the Copts had been good carpenters before Islam came into the region. When the Muslims came in the seventh century, the old workshops continued to produce woodwork for Muslim patrons, and the Islamic tradition built on the Coptic one. But with the coming of Islam, the carpenter was given a new briefing!” He added the last line with an enigmatic smile before leaving me to sketch the figure of St. George on horseback.

As Islam conquered Byzantine territories, which were rich in the tradition of icons, how was the new religion and its empire to express its faith and establish rule? Since portrayal of God, the saints, and the Prophet was forbidden in places of worship, representation was not a tool available to spread faith. The challenge for the Muslim artist was not simply a matter of omitting figurative imagery from the mosque, it was how to find a way to express the Divine without representation, how to create a sense of God, who is everywhere yet not visible.

“Read” was the first word Allah spoke to Muhammad in the cave of Hira in 610, commencing the Qur’anic revelation that continued for over twenty-three years. The Prophet, a onetime traveling merchant, was illiterate, but it was his miracle to become the messenger of the word of God. Unlike the Old or New Testaments, the Qur’an is considered by believers to be God’s word verbatim delivered to Muhammad through the Archangel Gabriel. The Prophet’s companions memorized the Qur’an, carrying it on as oral tradition, before realizing, soon after Muhammad’s death, that the word of God needed to be recorded. The act of copying and transcribing became central to Islam, elevating the written word—and the style in which it was written—to a level of importance unmatched in the other two Abrahamic religions. Arabic, the word, imbued writing with a sacred potential in the form of calligraphy.

In Islam, God is so often invoked and alluded to in daily life, and yet the ban on His representation is so strongly enforced. The Muslim artist turned to the one set of graphics with which God was most closely aligned: Arabic, the word, the sacred language of the Qur’an. By integrating Qur’anic Arabic into the sphere of the everyday, artists pioneered a method of conveying the omnipresence of God. They developed a remarkably fluid relationship between the visual arts and writing: expressions such as “Al-mulk Li-lah” (“Sovereignty is to God”) are found in ceramics from eighth-century Syria or fourteenth-century woodcarvings from Iran.

The extensive copying of the word of God is encouraged by the Qur’an, which states, “If the ocean were ink to write out the words of God, the ocean would be exhausted sooner than would the words even if we added another ocean like it.”

The principal script used for Qur’anic manuscripts from the seventh until the twelfth century was Kufic. Though an essentially angular script, artists found ways to improvise. Tenth-century Persian calligraphers developed Eastern Kufic, which is delineated by short strokes. Maghribi, evolved from Kufic script in North Africa (the Maghrib) and Spain around roughly the same time, is characterized by the rounding of the angles, creating semicircular loops and a different set of flourishes. The variations reflect geographical differences in the manner of regional dialects.

Naskh, the cursive “copyist’s” hand—once used for both the writing of government documents and the Qur’an—was refined by Ibn Muqla, a master calligrapher and vizier at the Abbasid court in Baghdad in the early tenth century. Ibn Muqla developed what is known as “al-aqlaam al-sitta,” or the six calligraphic styles. He attempted to standardize the cursive scripts to make them all well proportioned and thus more worthy of copying the Qur’an. By the tenth century there were said to be at least twenty different cursive styles of script.

One exquisite manuscript is known as the “Blue Qur’an,” because it is the only extant version from the period that uses indigo-dyed vellum. Written in gold in Kufic script without diacritical marks, which indicate the vowels in Arabic,

the Blue manuscript creates a sublime space of silence. The Qur’an speaks of itself as divine light, and gold becomes light on the page. While calligraphy aspires to match the sacredness of the message of God, in the “Blue Qur’an,” the sacred, in its silence, becomes almost tangible. The calligrapher traced the words as though the prayer was in the beauty of the line on the page, gold shining from the depth of the indigo.

The calligrapher saw himself as a medium through whom God’s creativity was channeled. He drew his inspiration from God, and God alone. While some work can be attributed to the hand of a particular master, such as Ibn al Bawwab, many extraordinary manuscripts are unsigned. And if they are signed, the signature often takes the shape of a self-effacing expression on the order of, “In the perishable hand of the servant of God …” Just as the Prophet said to his followers, “Muhammad was only a messenger and messengers died before him,” it was culturally ingrained that the artist was ephemeral, only a vessel into which God’s words were poured.

On a research trip conducted for the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1991—notes from which are contained in a yellow pad—I traveled to the libraries of Morocco, where in Marrakesh I met a remarkable old man, keeper of manuscripts. The encounter changed the way I look at Islamic art, forcing me to confront the fact that I came from a Muslim culture (I was born and raised in Tunisia) but was now studying Islamic art in the West.

Examining manuscript after manuscript, I grew disappointed with the absence of attribution to either a place or a person. The guardian of manuscripts (that’s how I referred to him in my notes) was amused. He admired each manuscript as though he was looking at it for the first time. “Some manuscripts were written in Spain but bound in Morocco, the writing styles so similar between the two,” he said, “that in some cases it is difficult to differentiate between them. Morocco and Spain were culturally one. The real question is: is the writing beautiful or moving, does it give you connection with something outside of yourself? Calligraphy alludes to something greater than the individual—that is a conception of a world that doesn’t have the me at its center. That’s why the artist is often absent. We cannot relate to these objects without awareness of the cultures that produced them.”

While copying the Qur’an, the calligrapher hoped to beautify the word of God, to aspire to embody its content, to write it in a way that was worthy of God’s message. In this way, the medium and the message became interconnected.

In other tenth-century manuscripts written in Kufic script, in dark-brown ink, the horizontal lines were so elongated they created a rhythm that is similar to the recital of the Qur’an, introducing a kind of musicality to the page. There are even times when calligraphy was executed in such a way as to render a pattern that is almost illegible.

“Fifty years,” said the guardian of manuscripts, “fifty years in the company of these manuscripts. That might seem a long time to you, but in fact it is nothing compared to the total of years spent in the tracing of the calligraphy of these manuscripts on the shelves. The Prophet Muhammad, peace be upon him, said, ‘The ink of the scholar is more holy than the blood of the martyr.’”

He proceeded to tell me a story. “Once a calligrapher was practicing calligraphy when a fire erupted. As the inhabitants of the building evacuated the place, they passed the calligrapher’s quarter and they called, ‘Save your life, move!’ But our calligrapher did not budge. The next party of people running for their lives passed by the calligrapher’s quarter, where they could see through the slightly open door candlelight still shimmering. ‘Run for your life!’ cried the last party. Finally our calligrapher lifted his head to say, ‘It has taken me twenty years to perfect the letter qaf. Please don’t disturb me!’”

Materials as diverse as earth and silk were at the service of the word of God and were sculpted and woven to speak it accordingly, creating a visual language that united different art forms in coherence. Qur’anic inscriptions gave Islamic art a character that is recognizable from Spain to Indonesia.

God surrounds us at all times, and so, too, do his words, painted on tiles or fashioned in brickwork, molded, carved, or incised. Decorating the stucco walls of the Alhambra Palace in Granada is the phrase “Wa la ghaliba illa Allah” (“There is no victor except God”). Some inscriptions are positioned so high on the walls or domes that although they may be visible, they cannot be read. In the seventeenth-century Shah Mosque in Isfahan, calligraphed inscriptions run around a mosaic-covered dome that is over 160 feet from the ground.

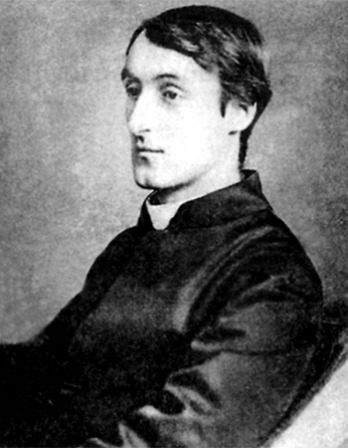

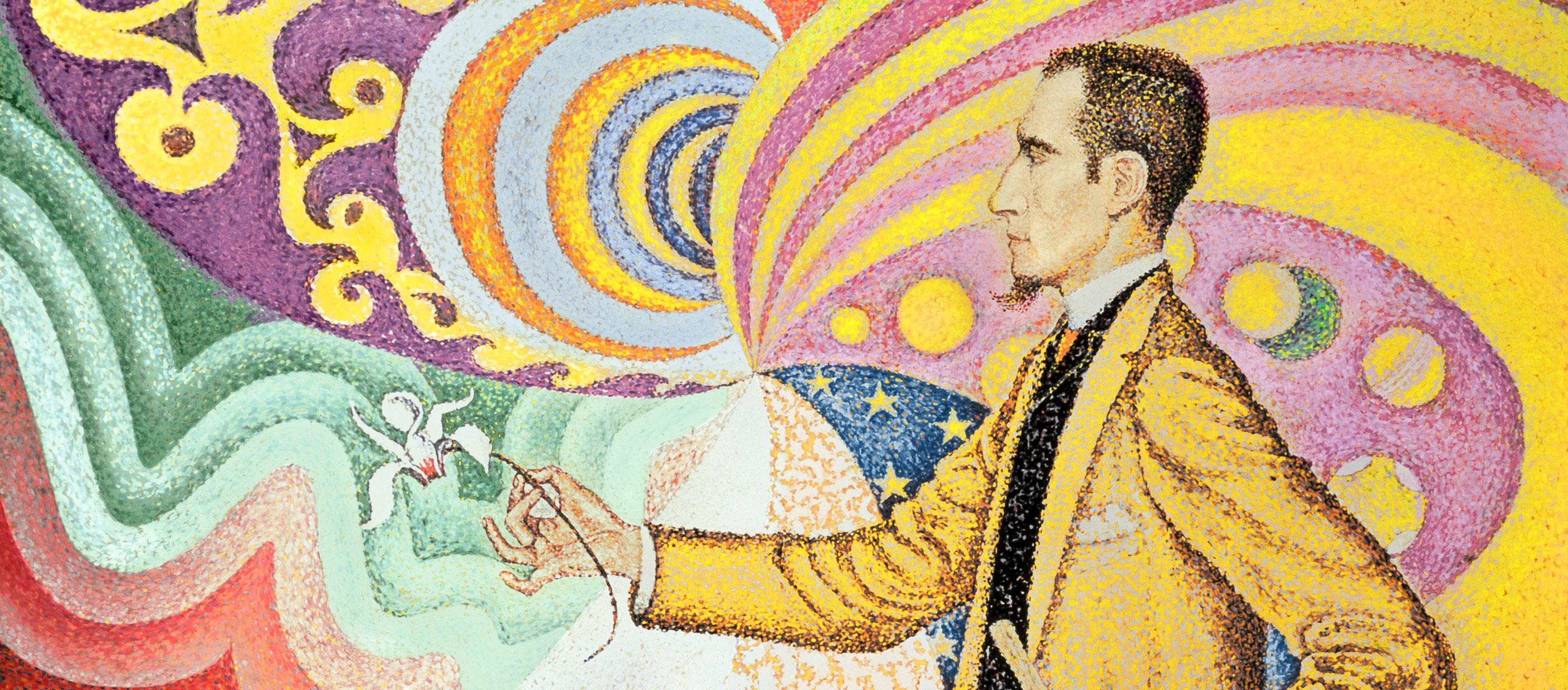

Opus 217. Against the Enamel of a Background Rhythmic with Beats and Angles, Tones and Tints, Portrait of Félix Fénéon in 1890, by Paul Signac, 1890. The Museum of Modern Art, New York, New York.

For Muslims, inscriptions within mosques come closest to the familiar iconography of Western Christian churches, whose walls and altarpieces with the consistency of clockwork depict Christ’s crucifixion, deposition, and resurrection. In the mosque, the focal point is the mihrab, a niche, essentially a symbol showing the direction of prayer toward the Kaaba in Mecca. (The Kaaba was a pagan temple with 360 idols in and around it that Muhammad in 630 smashed, establishing the concept of tawhid, or the Oneness of God, i.e., “Ashhadu an la ilaaha illa Allah, Muhammad rasul Allah.” (“There is no God but God, Muhammad is His messenger.”) The niche can serve as a metaphor for a door into another world, suggesting a passageway to the heavenly realm. By the very early eighth century, Islam had spread from Spain to central Asia, all the peoples united in directing their prayer to the same holy site as indicated by the mihrab. This niche is often adorned with calligraphy and the abstract motif of arabesque.

Mosques create an area of worship that reflects a faith that uses no intermediary between God and the worshipper. There is no priest to whom one can or might confess. For forgiveness, the believer has to address himself directly to God. Impelled by the faith to create a place of worship, to give a sense of God being omnipresent yet remaining invisible, the Muslim artist explored geometrical and stylised floral patterns to create a space of contemplation, opening a channel to the Divine—abstract beauty rendered in mathematical exactitude as a metaphor for God’s perfection. The profuse use of calligraphy enhances the abstract aspect of this contemplative space.

In its aspect of endless repetition, pattern alludes to the infinite and how God encompasses the universe—no end, no beginning. The overriding tendency in Islamic art is to fill space with ornamentation, a practice sometimes deemed excessive in the West. Instead of emulating fragments of the visible world, Islamic art seeks to give a sense of the world in its entirety. If not delineated by the outline of the object, or the architectural expanse, the patterns could go on multiplying forever.

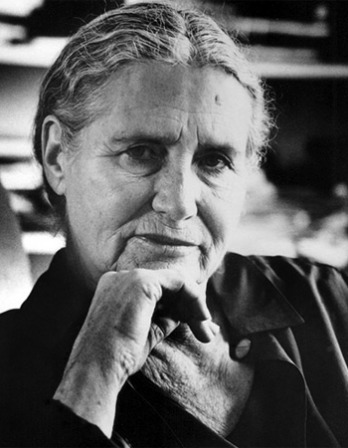

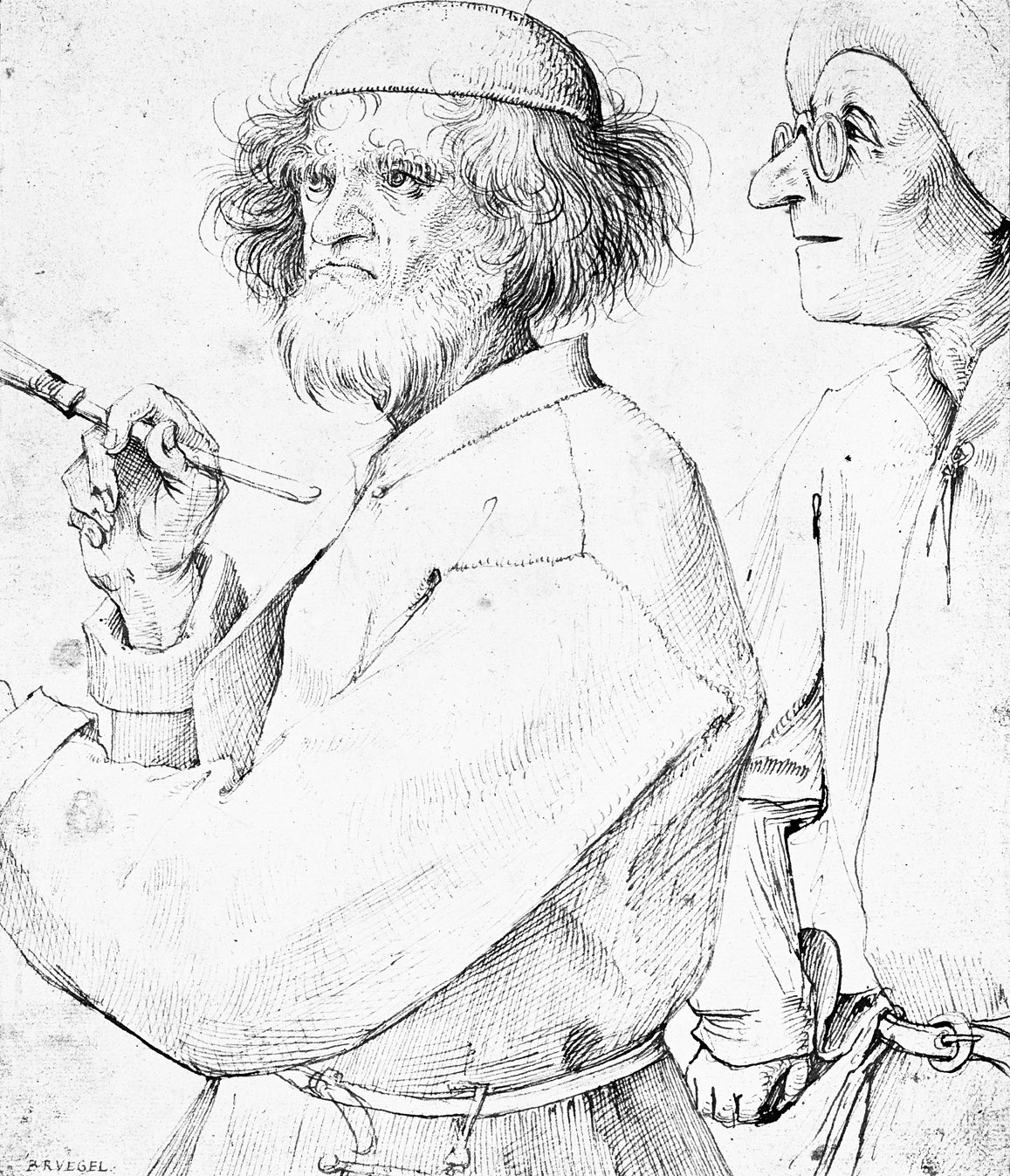

Painter and his Patron, by Pieter Brueghel the Elder, c. 1565. The Albertina, Vienna, Austria.

Since at least the early Renaissance, the use of perspective in European art centers everything on the eye of the beholder, with objects farther away from the viewer made smaller. This convention rarely appears in Islamic paintings, even the most “realistic” of the Persian miniatures. Oftentimes these miniatures tell stories that maintain a close bond between word and image, but like Chinese landscape paintings, the miniatures did not attempt to replicate nature as filtered through the human eye.

This understanding of the world produced a unified field of perception throughout the Muslim world—to so great a degree that although some regional styles can be distinguished, many objects can be attributed to various parts of the Islamic world at the same time. The Pisa Griffin that had stood atop the cathedral of Pisa for centuries (now in the Museo dell’Opera del Duomo) is about three feet high, marked by fluid linear rhythms and decorated with bands of Kufic calligraphy. On stylistic grounds scholars dated it to around the eleventh or twelfth centuries, but there the consensus ceased. Different scholars attributed it to Iran, Egypt, Tunisia, Spain, and Sicily, each on the basis of substantial arguments—a remarkable similarity. No fourteenth-century Italian pietà would ever be mistaken for a Flemish one.

Here I am reminded of the guardian of manuscripts in Morocco who laughed at my scholarly preoccupation with colophons and the signature of the artist. He said to me, “Of course Muslim artists wanted to be known and loved perhaps by their commissioners of the day but above all, they wanted to be loved by God. The Prophet, peace be upon him, is believed to have said, “Allah jameel yuhibb al-Jamal” (“God is beautiful and He loves beauty”). Beauty comes from and goes back to God. He is the beholder who sees. And beauty, according to the Muslim artist, was not for human eyes alone.”

It was in the Museum of Islamic art in Cairo during my 1987 (purple pad) trip that I came across a beautiful earthenware fragment, a filter that was originally placed at the bottom of the neck of a simple water jug. It was delicately decorated as though it were not earthenware but precious material. Why was there an exquisite image of a peacock inside the jug’s neck? It was so deliberate and yet served no purpose, the quiet beauty of this creature hidden. That is art. Even if no one sees it—especially if no one sees it.