There is a time to battle against nature, and a time to obey her. True wisdom lies in making the right choice.

—Arthur C. Clarke, 1979Humanity on the Wane

H.G. Wells changes climates.

The calm of evening was upon the world as I emerged from the great hall, and the scene was lit by the warm glow of the setting sun.

At first things were very confusing. Everything was so entirely different from the world I had known—even the flowers. The big building I had left was situated on the slope of a broad river valley, but the Thames had shifted, perhaps a mile from its present position. I resolved to mount to the summit of a crest, possibly a mile and a half away, from which I could get a wider view of this our planet in the year 802,701 ad. For that, I should explain, was the date the little dials of my machine recorded.

As I walked I was watchful of every impression that could possibly help to explain the condition of ruinous splendor in which I found the world—for ruinous it was. A little way up the hill, for instance, was a great heap of granite, bound together by masses of aluminum, a vast labyrinth of precipitous walls and crumbled heaps, amid which were thick heaps of very beautiful pagoda-like plants—nettles possibly, but wonderfully tinted with brown about the leaves, and incapable of stinging. It was evidently the derelict remains of some vast structure, built to what end I could not determine.

Looking around, with a sudden thought, from a terrace on which I had rested for a while, I realized that there were no small houses to be seen. Apparently, the single house, and possibly even the household, had vanished. Here and there among the greenery were palace-like buildings, but the house and the cottage, which form such characteristic features of our own English landscape, had disappeared.

“Communism,” said I to myself.

There were no large buildings toward the top of the hill, and as my walking powers were evidently miraculous, I was presently left alone for the first time. With a strange sense of freedom and adventure I pushed up to the crest.

Diquís andesite sphere, Costa Rica, ninth to sixteenth century. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of the Austen-Stokes Ancient Americas Foundation, 2012.

There I found a seat of some yellow metal that I did not recognize, corroded in places with a kind of pinkish rust and half smothered in soft moss, the armrests cast and filed into the resemblance of griffins’ heads. I sat down on it, and I surveyed the broad view of our old world under the sunset of that long day. It was as sweet and fair a view as I have ever seen. The sun had already gone below the horizon, and the west was flaming gold, touched with some horizontal bars of purple and crimson. Below was the valley of the Thames, in which the river lay like a band of burnished steel. Here and there rose a white or silvery figure in the waste garden of the earth, here and there came the sharp vertical line of some cupola or obelisk. There were no hedges, no signs of proprietary rights, no evidences of agriculture; the whole earth had become a garden.

So watching, I began to put my interpretation upon the things I had seen, and as it shaped itself to me that evening, my interpretation was something in this way: it seemed to me that I had happened upon humanity upon the wane. The ruddy sunset set me thinking of the sunset of mankind. For the first time I began to realize an odd consequence of the social effort in which we are at present engaged. And yet, come to think, it is a logical consequence enough. Strength is the outcome of need; security sets a premium on feebleness. The work of ameliorating the conditions of life—the true civilizing process that makes life more and more secure—had gone steadily on to a climax. One triumph of a united humanity over nature had followed another. Things that are now mere dreams had become projects deliberately put in hand and carried forward. And the harvest was what I saw!

After all, the sanitation and the agriculture of today are still in the rudimentary stage. The science of our time has attacked but a little department of the field of human disease, but even so, it spreads its operations very steadily and persistently. Our agriculture and horticulture destroy just here and there a weed and cultivate perhaps a score or so of wholesome plants, leaving the greater number to fight out a balance as they can. We improve our favorite plants and animals—and how few they are—gradually by selective breeding; now a new and better peach, now a seedless grape, now a sweeter and larger flower, now a more convenient breed of cattle. We improve them gradually, because our ideals are vague and tentative, and our knowledge is very limited; because nature, too, is shy and slow in our clumsy hands. Someday all this will be better organized, and still better. That is the drift of the current in spite of the eddies. The whole world will be intelligent, educated, and cooperating; things will move faster and faster toward the subjugation of nature. In the end, wisely and carefully we shall readjust the balance of animal and vegetable life to suit our human needs.

This adjustment, I say, must have been done, and done well: done indeed for all time, in the space of time across which my machine had leaped. The air was free from gnats, the earth from weeds or fungi; everywhere were fruits and sweet and delightful flowers; brilliant butterflies flew hither and thither. The ideal of preventive medicine was attained. Diseases had been stamped out. I saw no evidence of any contagious diseases during all my stay. Even the processes of putrefaction and decay had been profoundly affected by these changes.

Social triumphs, too, had been effected. I saw mankind housed in splendid shelters, gloriously clothed, and as yet I had found them engaged in no toil. There were no signs of struggle, neither social nor economical struggle. The shop, the advertisement, traffic, all that commerce which constitutes the body of our world, was gone. It was natural on that golden evening that I should jump at the idea of a social paradise.

The difficulty of increasing population had been met, I guessed, and population had ceased to increase.

But with this change in condition comes inevitably adaptations to the change. What, unless biological science is a mass of errors, is the cause of human intelligence and vigor? Hardship and freedom: conditions under which the active, strong, and subtle survive and the weaker go to the wall; conditions that put a premium upon the loyal alliance of capable men, upon self-restraint, patience, and decision. And the institution of the family, and the emotions that arise therein, the fierce jealousy, the tenderness for offspring, parental self-devotion, all found their justification and support in the imminent dangers of the young. Now, where are those imminent dangers? There is a sentiment arising, and it will grow, against connubial jealousy, against fierce maternity, against passion of all sorts; unnecessary things now, and things that make us uncomfortable, savage survivals, discords in a refined and pleasant life.

Concrete Jungle, from the series Anthropic Pressure, by Nicolas Derné, 2017. © Nicolas Derné, courtesy the artist.

I thought of the physical slightness of the people, their lack of intelligence, and those big abundant ruins, and it strengthened my belief in a perfect conquest of nature. For after the battle comes quiet. Humanity had been strong, energetic, and intelligent, and had used all its abundant vitality to alter the conditions under which it lived. And now came the reaction of the altered conditions.

No doubt the exquisite beauty of the buildings I saw was the outcome of the last surgings of the now purposeless energy of mankind before it settled down into perfect harmony with the conditions under which it lived—the flourish of that triumph which began the last great peace. This has ever been the fate of energy in security; it takes to art and to eroticism, and then come languor and decay.

Even this artistic impetus would at last die away—had almost died in the time I saw. To adorn themselves with flowers, to dance, to sing in the sunlight; so much was left of the artistic spirit, and no more. Even that would fade in the end into a contented inactivity. We are kept keen on the grindstone of pain and necessity, and it seemed to me that here was that hateful grindstone broken at last.

H.G. Wells

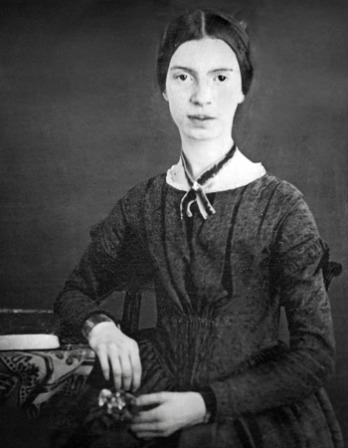

From The Time Machine. After working as a draper’s apprentice, Wells at the age of eighteen won a scholarship to study under zoologist T.H. Huxley; it was then he was first inspired to write. Eleven years later, he published The Time Machine, his first novel, in which he envisioned two future races of people, modeled after the Victorian ruling and laboring classes. “I do not think that in the present phase of human affairs there is any possible Great Good Place,” he wrote in 1932. “The drama of the immediate individual life will be subordinate more and more…to beauty and truth, to universal interests and mightier aims.”