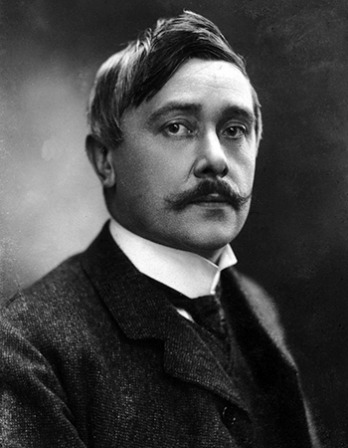

Thomas Browne

Religio Medici,

1643

Religio Medici,

There is no torture to the rack of disease nor any poniards in death itself like those in the way or prologue unto it. “I don’t want to die, but I’m not worried about being dead.” Were I of Caesar’s religion, I should be of his desires, and wish rather to go off at one blow than to be sawed in pieces by the grating torture of a disease. Men that look no further than their outsides think health an appurtenance unto life and quarrel with their constitutions for being sick, but I, that have examined the parts of man and know upon what tender filaments that fabric hangs, do wonder that we are not always so; and, considering the thousand doors that lead to death, do thank my God that we can die but once. ’Tis not only the mischief of diseases and the villainy of poisons that make an end of us; we vainly accuse the fury of guns, and the new inventions of death—it is in the power of every hand to destroy us, and we are beholden unto everyone we meet, who doth not kill us. There is therefore but one comfort left, that though it be in the power of the weakest arm to take away life, it is not in the strongest to deprive us of death. God would not exempt himself from that. Certainly there is no happiness within this circle of flesh; nor is it in the optics of these eyes to behold felicity. The first day of our Jubilee is death; the devil hath therefore failed of his desires; we are happier with death than we should have been without it: there is no misery but in himself where there is no end of misery; and so indeed, in his own sense, the Stoic is in the right. He forgets that he can die, who complains of misery: we are in the power of no calamity, while death is in our own.