No punishment has ever possessed enough power of deterrence to prevent the commission of crimes.

—Hannah Arendt, 1963Murder in Black & White

A history of film noir, America’s cinematic take on life on the bottom.

By Nathaniel Rich

Film noir title screens.

A man leaking blood from his chest, staggering down an empty street, the wet black pavement mirroring the dim globes of streetlamps. The scissoring shadows of a backlit fire escape, of a spiral staircase, of prison bars. The clickety-clack of stilettos as a woman runs down a steep hill hugging tight her mink coat with white-gloved hands. The drawn gun; the eyes widening with terror. The fedora brim pulled low over the brow; the lounge singer’s dress pulled low over the cleavage.

The iconography of film noir is now as embedded in the American public consciousness as the cowboy hat, the apple pie, the string bikini. In the last ten years, as the genre has achieved an unprecedented popularity, noir has become an aesthetic, an attitude, the inspiration for magazine fashion spreads and costume parties. But the crimes depicted in the actual films are rarely glamorous. A film noir’s original act of violence is often an ugly mistake, committed out of desperation, or by accident. A quintessential example of the noir premise can be seen in Otto Preminger’s Where the Sidewalk Ends (1950). Detective Mark Dixon (Dana Andrews), a New York cop on probation for repeated acts of brutality, accidentally kills a robbery suspect with a right hook—the suspect, as it turns out, had a metal plate in his head, courtesy of a wartime injury. To prove his innocence and save his career, Dixon must commit a chain of increasingly criminal acts: coverup, frame job, conspiracy, murder. Things get only more difficult for Dixon when he falls in love with the daughter of the man he framed for the original murder.

In noir, it’s the desire to do good that drives men to do horrible things. This irony spurred the development of the genre in the early 1940s. Despite its focus on the criminal underworld, film noir did not come out of a desire to address real concerns about American crime. As such, it was a major break with the popular gangster genre of the 1930s, when Prohibition and the gangs that profited from it inspired films like The Public Enemy (1931), Scarface (1932), and Angels with Dirty Faces (1938). More subtly, the gangster films doubled as Depression-era Horatio Alger tales, in which a poor street kid using his wits ascends the ranks of the criminal underworld until, in the words of Ricco in Little Caesar (1930), he “gets to the top.” “Made it, Ma! Top of the world!” screams James Cagney at the end of the noir White Heat (1949), playing on the reputation he made as the leading star of the gangster period. The gangster ultimately receives his comeuppance, but rarely does he regret the life he has chosen.

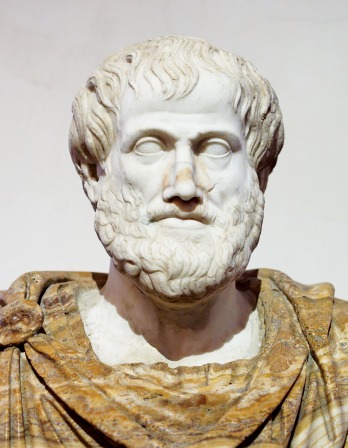

The Damned Soul or Fury, by Michelangelo Buonarroti, c. 1525. Uffizi Gallery, Florence, Italy.

The subject of noir, however, is life on the bottom. Its heroes are doomed men who start low, only to sink lower. Noir heroes tend to look like they’ve just been peeled off the bottom of a shoe. It’s a slanty-eyed and poorly shaven cast of characters: the crooked beat cop, the mob henchman, the private eye, the convict who wants to reform his ways but is blackmailed into attempting one last score.

Or the veteran trying to adapt to square life, only to be haunted by the ghosts of war. For the real subject of early film noir is not crime in America, but war in America, specifically the shadow cast by World War II on American society in the 1940s and ’50s. In film noir, crime is used as metaphor to examine the darker impulses and anxieties that lay hidden beneath the boosterism of the postwar era—the sense that, despite the country’s military triumphs, we had suffered great, irredeemable damage. That we had learned ugly things about ourselves, that an urge to commit acts of violence lies within all men, and that man’s capacity for evil and greed has no limit. Faced with the enormity of the Holocaust and the nuclear bomb, previous standards of moral behavior seemed absurdly quaint. In film noir, the criminal act is often a last resort, the only option available to the alienated and dispossessed.

While the newsreels celebrated the return of the troops and the destruction of the Axis powers, these films viewed the new American society with a leering, jaundiced eye. Noir transfigured the American dream into the American nightmare. War films of the time could only trumpet a vision of American might, glory, and success. Audiences knew this version didn’t ring true. Hollywood took note, and the genre exploded. Though it’s impossible to seize upon an accurate figure, it is safe to say that at least seven hundred noir films were produced during the classic period, which is commonly defined as 1941–1958.

Some early noirs directly portrayed the damage wreaked by the war. In The Blue Dahlia (1945), written by Raymond Chandler, war veteran Johnny Morrison (Alan Ladd) returns home to learn that his wife has been cheating on him. When she’s found murdered, Johnny is the prime suspect. Though the studio ordered a rewrite, in Chandler’s original screenplay the murderer turns out to be Johnny’s wartime buddy Buzz, who has committed the crime in a crazed, blacked-out state, a consequence of wartime trauma. In Act of Violence (1948), veteran Frank Enley (Van Heflin), trying to readjust to suburban life, is haunted by a crazed comrade who shows up at his door seeking revenge for a war crime Enley may or may not have committed. The disturbing Try and Get Me (1950) is about a bitter, poverty-stricken war vet who enters a life of crime in order to support his pregnant wife and young son—and soon finds that he can’t go back.

Yet most films from noir’s classic era deal with these issues in an allusive manner. They expose the familiar symbols of postwar prosperity as hollow shams, covers for moral perversity. It’s no coincidence that many of the films open in elegant settings—penthouse apartments, ritzy mansions, country estates—only to end up in gritty underground bars and flophouses once the characters begin their inevitable downward spiral. Their internal despair finds reflection in the seamiest corners of urban life.

There is no more extreme example of the disjunction between outward appearance and inner depravity than Preminger’s masterful Laura (1944), about a set of high-society New Yorkers whose most animalistic desires are revealed during an investigation into the mysterious murder of a beautiful young advertising executive. As we learn more about each suspect, we soon realize that the more polished a character’s social persona, the more sinister are his inner demons. A bizarre, gothic San Francisco version of this setup is The House on Telegraph Hill (1951), in which a concentration-camp survivor poses as her dead friend—a wealthy heiress—with disastrous results. The glamorous world of Hollywood turns perverse and vicious in, most notably, Sunset Boulevard (1950) and In a Lonely Place (1950), while a Broadway theater is the setting for a brutal bludgeoning death in The Velvet Touch (1948). In films like The Pitfall (1948) and The Prowler (1951), the idyllic suburban home is reimagined as a prison; rural life gets the same treatment in The Postman Always Rings Twice (1946) and On Dangerous Ground (1952). The country’s most noble institutions—the police force (The Big Heat [1953]), the newspaper industry (Ace in the Hole [1951]), and even the university campus (The Accused [1949])—are revealed to be seedy hotbeds of corruption, mob infiltration, criminal conspiracy, and brutality.

Film noir is itself a shadowy term, since it connotes not only a hardboiled mentality but also a specific cinematic style, distinguished by stark chiaroscuro black-and-white cinematography, obsessive use of shadow, and expressionistic camera angles. As such, there are numerous films that are classified as noir purely on an aesthetic basis, but lack its dark spirit. In the late ’40s, for instance, there came a trend of documentary-style policiers—the most impressive of which are Kiss of Death (1947), The Naked City (1948), and T-Men (1948)—that are narrated from the perspective of a law-enforcement agency and follow the successful prosecution of a crime. Most of these films are based on real crimes and are packed with hyperrealistic and usually tedious details about the criminal investigation. They lack the tone of despair that so strongly pervades the noir canon, and seem to regress to the propagandistic efforts of the war years. As might be expected, this period of noir did not last long. By the early fifties, it had been replaced by an increasingly abstract, jazzy, paranoiac, and horrific style that reached its apotheosis with one of the greatest films of this or any other genre: Robert Aldrich’s Kiss Me Deadly (1955).

From the opening shot—a barefoot blonde wearing nothing but a trench coat, running down a highway at night in a state of high panic—the film taps into a sense of dread more harrowing than any of its predecessors. This is because we’re no longer in Los Angeles, or New York, or San Francisco, but in what the noir critic Eddie Muller calls “Dark City”—“a fever dream of modern life.” Some of the locations may seem familiar, but they are so altered by shadow and fog, or by oblique camera angles, that it seems as though we’ve passed through Alice’s looking glass. Throughout the film there is a pervasive sense of disembodiment, of detachment from the real world. The only people we meet are wise guys, femme fatales, G-men, and bizarre secondary characters like Nick, the Greek mechanic who speaks in car noises—va va voom—instead of English.

Familiar noir conventions are referenced, only to be manipulated and tossed aside. The barefoot blonde serves as the femme fatale, luring Mike Hammer (Ralph Meeker), a narcissistic, impervious, ruthless private eye, into a murderous mystery. But by the second scene, she’s gone—shortly after Hammer pulls over to pick her up, a car rushes out of the darkness and smashes into them. We cut to an abandoned shack, where the blonde is herself disembodied: screaming, naked, shot from her knees down, she is tortured to death with a pair of pliers by men whose faces we can’t see. When Hammer comes back from the dead several weeks later, he starts looking for answers. Before long, he finds himself dodging both gangsters and government agents in pursuit of a mysterious, radioactive suitcase that is a modern-day Pandora’s Box. Its contents, we learn, may bring about the end of the world.

In Kiss Me Deadly, the stakes move beyond private moral dilemmas into a relentless grappling with larger, existential fears, focused around the threat of nuclear apocalypse. There are a few earlier films that explore Cold War A-bomb paranoia—Orson Welles’ brilliant Lady from Shanghai (1948), as well as a group of Red Scare noirs—but not with such single-minded focus. The crimes committed in the film, though often shockingly violent and distressing, are made to pale in comparison with the greater crime of man’s mindless flirtation with self-annihilation.

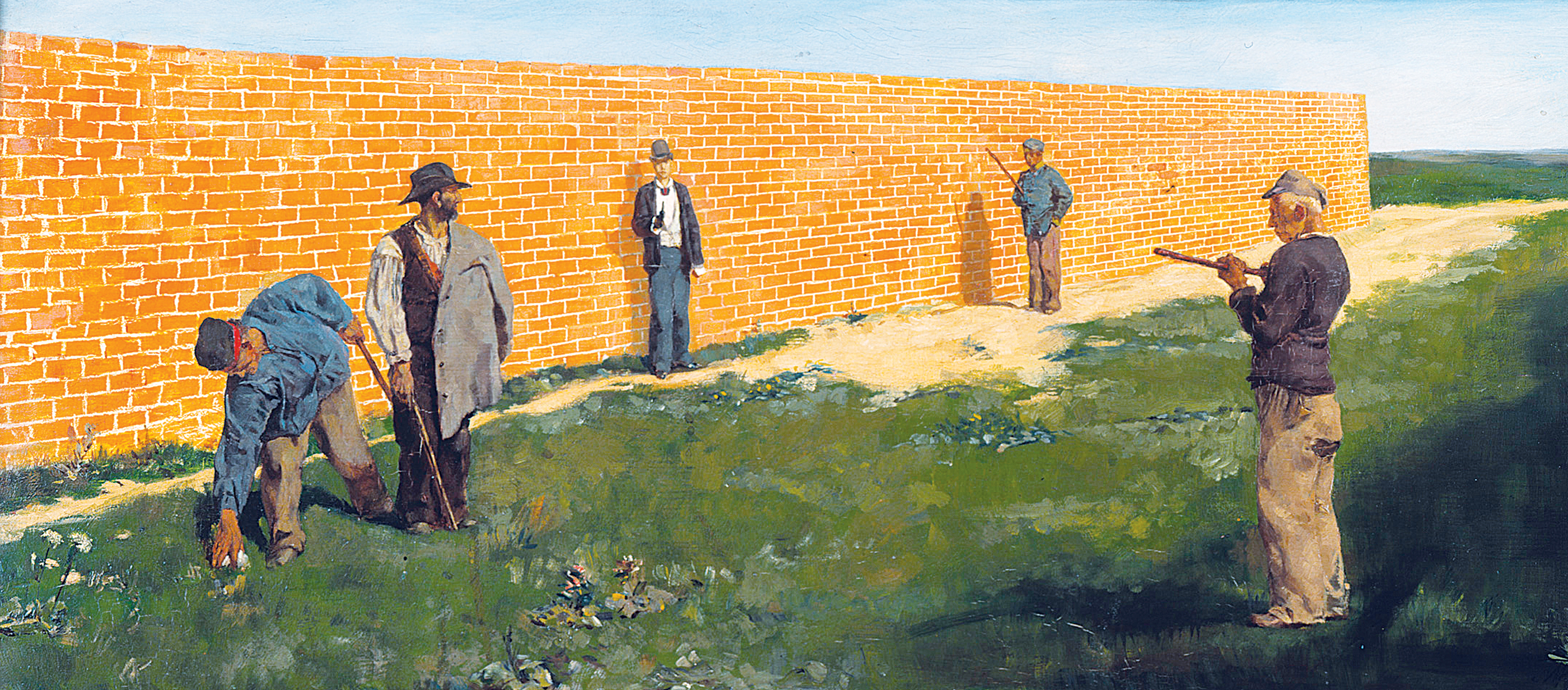

The Walker, by Max Klinger, 1878. Alte Nationalgalerie, Berlin, Germany.

Many critics contend that the classic noir era officially came to a close with Welles’ Touch of Evil (1958), the most self-conscious, exaggerated treatment of the noir formula yet. I’d argue that Alfred Hitchcock’s Vertigo, which came out just one week later, went even further, injecting the noir sensibility into a modern-day ghost story, eschewing noir’s familiar, expressionistic black and white for the lush palette of VistaVision. With Vertigo, Hitchcock proved that the heightened sense of dread and paranoia that defined the genre could be rendered with other cinematic techniques in color just as effectively as the black and white.

Crushed under the weight of its own self-referentiality, and by the popularization of television and color film, the classic era of film noir was over. It wasn’t only that the noir style had been done to death. America had also changed. World War II was nearly fifteen years gone, and the malaise and cynicism expressed by noir seemed less relevant. For the time at least, the good guys had won.

But in the late ’60s a new type of film noir, which borrowed heavily from the noir tradition but departed from its conventions in significant ways, began to emerge. Many of these so-called neo-noirs were made by directors who had come of age during the classic noir period and had gone back to study it as film students in the 1960s. (The term “film noir” was coined by the French film critic Nino Frank in 1946 but didn’t enter the popular lexicon until 1955, when it appeared as the subject of a book titled Panorama du film noir américain, written by the French critics Raymond Borde and Étienne Chaumeton. It took another fifteen years before noir was taken seriously in American critical circles, long after the western, the gangster film, and the musical had become widely studied.) One of the seminal American essays on the form, “Notes on Film Noir,” was written in 1972 by Paul Schrader, who shortly afterward wrote the script for the neo-noir par excellence, Taxi Driver.

Film noir of this period focuses on certain central themes of film noir and blows them up to an obsessive degree. Suitably, Blow-Up (1966)—though directed by an Italian, Michelangelo Antonioni, and set in London—provides an almost literal example of this technique. An act of voyeurism, a common noir trope, obsesses a photographer who becomes convinced that a photograph he has taken contains evidence of a murder. His obsession grows until it blots out everything else. Francis Ford Coppola’s The Conversation (1974) employs a similar premise: Harry Caul (Gene Hackman) is a professional surveillance man who believes he has taped a conversation that contains evidence of a murder. Harry is so consumed by his paranoia that he becomes certain he himself is being bugged. Coppola’s film begins where most noirs end—with our hero in a state of total despair. As Harry’s obsession deepens, it becomes clear that there’s only one way out of the maze he has created for himself. It’s not to commit a crime against another person, but to destroy himself.

The heroes of John Boorman’s Point Blank (1967) and Peter Yates’ Bullitt (1968) are men deadened by their implacable need for revenge. In Point Blank, Lee Marvin’s stone killer Walker is so hell-bent on recovering the $93,000 that has been stolen from him that he’s rendered virtually speechless. With his .38 in tow—at the time the largest revolver ever to appear on the big screen—he hunts down the criminals that crossed him, one by one. His manner is so cold that he seems inhuman, and indeed the haunting final scene of the film indicates that this might just be the case.

Stylistically, these films follow the example set by Kiss Me Deadly: a descent into an almost surrealistic world pervaded by dread and criminality, by characters so dominated by a single perverse obsession that they cease to resemble human beings. Yet at the same time, the neo-noirs of the late sixties and seventies recall the earliest noir films in their gritty, realistic depiction of the urban landscape.

By the mid-seventies, the country had suffered the worst economic collapse since the Great Depression (until now). Ten million American workers were unemployed, a figure that didn’t count the millions of others, especially young blacks, who had never been employed in the first place. In 1974, spurred by 12-percent inflation, the costs of living surged to near-record highs, even as real wages plunged. The pain was felt most acutely in the nation’s largest cities, which experienced astronomical increases in crime and poverty rates. There was a very real fear that many of America’s greatest cities—including New York—might be lost for good.

The more religious a country is, the more crimes are committed in it.

—Napoleon Bonaparte, 1817These anxieties are reflected vividly by the noir of this period. The subject of Taxi Driver is as much the decay of a bankrupt New York City as it is the degenerative mind of Travis Bickle. The Los Angeles of Point Blank and Robert Culp’s despairing Hickey and Boggs (1972) alternates between bombed-out, post-apocalyptic desolation and seedy ghetto life. San Francisco is never uglier on the screen than in The Laughing Policeman (1973) and in the Dirty Harry series. In the classic noir era, crime was relegated to the underworld: the alleyway, the flophouse, the underground gambling ring, the dive bar. In the seventies in the American inner city, violence couldn’t be avoided. It was everywhere. In neo-noir, crimes occur in the middle of busy squares—like Union Square in The Conversation—in broad daylight.

There’s a scene that dramatizes this to an almost absurd degree in Dirty Harry (1971). Detective Harry Callahan (Clint Eastwood), eating a hot dog at a diner, spots a bank robbery in progress across the street. Though visibly annoyed by the interruption to his meal, he manages to kill two criminals and apprehend another. In the process, however, an entire block of downtown San Francisco is demolished—cars crash, a fire hydrant explodes, a flower stand is obliterated, gunshots spray buildings, people. What’s often missed in the scene is the response of the passersby on the street. As soon as the gunplay is over, they go on with their business, as unflappable as Harry himself, who returns to his hot dog. Crime is rampant, the stuff of everyday life. What was unusual was a figure like Dirty Harry—a cop determined to see justice done, no matter the personal risk.

The Dirty Harry series may take this premise a bit too far—critics have called the films fascistic for the extent to which Harry bends (or ignores) the law in order to put criminals away. But they reflect a sense, prevalent at the time, that America’s cities were careening out of control, sliding into a barbaric vortex of wanton criminality. Classic film noir focused on suppressed anxieties. Neo-noir addressed fears that openly plagued society, fears that were realized in the startling depredation of America’s cities.

The remarkable revival of interest in film noir in the past decade now seems darkly prescient. During a period distinguished by denial about the impact of foreign wars and the health of the economy, the rekindled interest in noir may have served as a small token of evidence of a growing sense of anxiety. Indeed, many of the best new films of the last decade have been made by directors working very consciously within the noir tradition: David Lynch’s Lost Highway (1997), Mulholland Drive (2001), and to a lesser extent, Inland Empire (2006); David Cronenberg’s A History of Violence (2005) and Eastern Promises (2007); Darren Aronofsky’s Pi (1998); Martin Scorsese’s The Departed (2006); David Fincher’s Zodiac (2007); Anthony Minghella’s The Talented Mr. Ripley (1999); Sidney Lumet’s Before the Devil Knows You’re Dead (2007); and two very different takes on noir conventions by the Coen Brothers, No Country for Old Men (2007) and Burn After Reading (2008).

Crime in America has again gone underground. The brutality of the fighting in the overseas wars, the torture of suspects in security bases, are hidden from view—as are the bloodless crimes committed by modern-day gangsters like Bernard Madoff. These stories beg a new film noir, films that explore our anxieties about unseen crimes and the indelible injuries they’ve left us. We want new Mark Dixons, new Dirty Harry Callahans. We want Walker, back from the dead, settling things with his .38—even if we know it’s just a dream.