Why listen to me? I can only predict epidemics and plagues.

—Larry Kramer, 1992

Production still from Oedipus Rex, directed by Pier Paolo Pasolini, 1967. © Arco Film / The Kobal Collection.

My father likes to talk to people, ask them questions, tell them stories. More than once, if I found myself reading, or watching TV, or just silently staring into space, he’d sit next to me and order: “Talk!” I’d bristle, but then I’d talk, of course. It’s not just that he cannot stand silence, or endure the thought that people have nothing to say to each other. It’s also his voracious curiosity—everyone, he assumes, has some story to tell, not least his professionally storytelling son. He expects other people to reveal themselves to him by way of stories. Silence is the death of narration, and thus of love.

Once, we were visiting my wife Teri’s parents in Pensacola Beach, Florida, and my parents came from Canada (where they have lived for the past twenty-three years) to join us for Christmas. Teri and I had married earlier that year, which was when my parents had encountered her parents and got splendidly along. Now, in Pensacola Beach, my parents spent time with her extended family, which, like my family, frequently gets together and features untold numbers of cousins and friends who have been absorbed into the kinship. My parents saw that the essential structure and practices of an African American family are very much like those of our Bosnian one. But one thing was somewhat lacking, however—Teri’s family didn’t do much of what my family did (and does still): they didn’t tell stories the way we did. Their history, for whatever reason, was not entirely available by way of public narration.

Thus, as we walked one balmy day along the splendid white-sand beach, seabirds coasting over our heads, clouds scarce and meringue, my father said to my wife: “Teri, tell me about your family. What bad happened?”

Teri was gracious but could not satisfy his curiosity. Apart from the general calamity of being black in America—applicable to an entire population, even if not necessarily equally—there were few family disasters to talk about. My father found that perplexing, even a bit disappointing—for if nothing bad had happened, it was hard to imagine how any stories could be forthcoming. If nothing bad happened, what do we have to talk about?

Teri knew, of course, that my parents had ended up as refugees in Canada, escaping the siege of Sarajevo. She knew that bad things had happened in our family, the baddest one being the war in Bosnia. But this was one of those moments when I felt compelled to interfere and explain my parents to my wife, to establish and introduce the theoretical foundations of their thought system, to instruct her—and anyone willing to submit and listen—on the ways in which trauma alters the very structure of the world and reality. For I understood instantly why my father would ask a question like that. I recognized his compulsion. The “what bad happened” was a shorthand (or longhand) for catastrophe. He asked her to lead him into the history of her family by way of outlining the catastrophes that defined it—for that’s how he would tell the story of our family: the wars, displacements, losses, struggles. There is no history without catastrophe; to outline a history one had to narrate its catastrophes. And what could not be narrated could not be understood. A family—or a world, or a life—without a catastrophe was incomprehensible, because it was an impossible proposition. If catastrophe (according to the theory of tragedy) is the dramatic event that initiates the resolution of the plot, then its absence suggests a possibility that the tragic plot will never be resolved. A catastrophe, in other words, might be a trap, but it also allows for a narrative escape. If you were lucky enough to have survived the catastrophic plot twist, you get to tell the story—you must tell the story.

I’m of a staunch belief that anything that can be said and thought in one language can be thought and said in another. The words might have a different value or interpretative aura, but there is always more than enough overlapping not to dismiss the project of translation, which is essential not only to the project of literature, but to the project of humanity as well.

But then there is the Bosnian word katastrofa, which, most obviously, comes from the same Greek word (katastrophe [καταστροφή], meaning overturning) as its English counterpart catastrophe. But in Bosnian—or at least in the language my family uses—katastrofa has a substantially different value and applicability than catastrophe has in English. We use it all the time, deploying it in the contexts that would be less appropriate in English. My mother would thus reprimand my father by saying, “Ti si, ćale, katastrofa!” (translatable as: You, Pop, are a catastrophe!) because he left a trail of dirty socks all the way to the bedroom. Or my father, in his report on a pipe bursting in their house wall, would use katastrofa to refer to the necessity of digging through said wall to find the source of the leak. My sister, who lives in London, would describe the leaden January skies depressingly looming over England and her head as katastrofa. And I could apply katastrofa to, say, the inability of Liverpool FC to defend corner kicks, or to the realization that I’m in the bathroom without toilet paper and the nearest roll is a hallway away. One of the few Bosnian words Teri understands is katastrofa, mainly by way of hearing me bemoan various unfortunate turns of events.

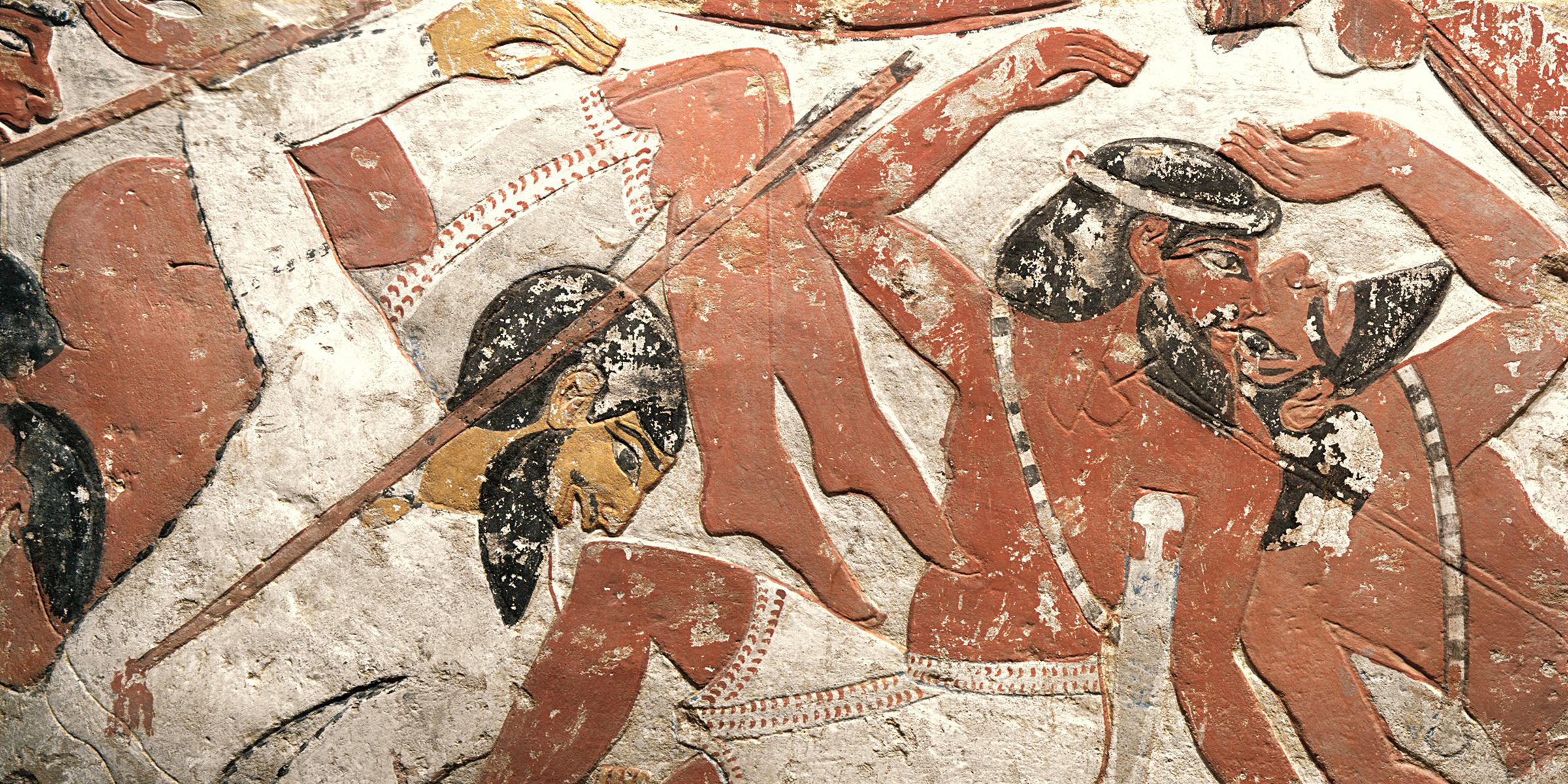

Block from a relief depicting a battle, reused in the foundation of the Theban mortuary temple of Ramses IV, c. 1400 BC. © The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Rogers Fund and Edward S. Harkness Gift, 1913.

None of this suggests that we don’t take the possibility of catastrophe seriously. On the contrary, the ease with which the word katastrofa is applied is related to its very ubiquity. Rather than existing exclusively in magnanimous, tragic dimensions, katastrofa is everywhere, its particles always shimmering like shrapnel on a sunny day.

Against their will, despite their desires, my parents are experts on katastrofa. I called them not so long ago to discuss their theoretical positions on the idea.

Without a doubt the most recent war was the greatest catastrophe in their lifetimes. (World War II was part of their childhood, but they were less traumatized by it, because their youth turned out to be pretty good.) My mother hadn’t expected the war to come, so it crashed into her life like a meteorite, and she still remembers the shock: the shelling, the curfew, the dissolution of her routines, her inability to fit the fact of war into the structure of reality within which she operated, saying to me, who called her from Chicago in the spring of 1992: “It’s going to stop soon, they’re already shooting less than yesterday.” And she remembers how everything they had worked for was erased overnight, not only being rendered meaningless, but also irreversibly destabilizing the very possibility of any structural permanence in their subsequent life. After the experience of war, she couldn’t sustain her belief in the inertia of reality—in the force that makes things continue as they are. She claims that her mind now rejects the possibility of another war, but the unnatural rupture made any kind of stability suspect. Back before the war, she, like many, was protected by the unimaginability of the unimaginable—a comfortable, if false, assumption that what cannot be imagined cannot happen, or even be happening. Now, she would hide behind the unimaginable, but what has already happened is always necessarily imaginable, and thus has that screen been shredded. To her, being old or sick is not a katastrofa—for that is, she says, natural—so she’s not afraid of it. It’s not that she fears war either—what she fears is that something will rupture her newly acquired (very Canadian) stability, that something might undo that particular reality.

My father was also traumatized by the war, but what he experienced as a katastrofa—a very personal one, he says—was primarily the rupture in the continuity of human nature. Before the war, he could believe in the stable goodness (or not-goodness) of people—they were who they were and you knew who they were; you avoided the bad ones, liked the good ones. What catastrophically shocked him was the abrupt shift he saw among some of his friends and acquaintances from neighbors into haters, from good to bad, from decent people into killers—that was the unimaginable for him, that overturning of human nature. When I ask him if he spends time expecting another katastrofa, as yet unimaginable, he says, “We’re old. There might be a katastrofa, but we won’t be around, so we don’t care.”

As for my sister, who has switched career paths in her forties to become a psychotherapist, she appears clear-eyed about the whole thing. “Katastrofa is the imaginary (and sometimes real) actualization of the worst possible outcome of a given situation,” she wrote to me. “The situation could vary from a missed bus or burned lunch to death and war.” She went on: “Katastrofa is the state of expectation of the worst, as well as preparation for avoidance, for the struggle against or the managing of the outcome. That state is sometimes conscious, but it is permanently subconscious.” She also thinks—and I agree—that there is some cultural determination to this perpetual expectation. We both remember the slogan, attributed to Comrade Tito himself and repeated to all the children and citizens of Yugoslavia for decades before the war: “We must live as though peace will last for a hundred years, and be ready as though war will start tomorrow.” (And the war did start tomorrow.) My father recalls his father (Ivan) firmly believing that it was impossible to live for fifty years without experiencing war—Grandpa Ivan himself had experienced two world wars. And if scientists are right in claiming that trauma can alter the genetic code, which can then be passed to ancestors, then katastrofa is inscribed in my genes.

I also asked my parents what the opposite of katastrofa would be. “Normal life,” they said, in unison. To them, normal life is a self-evident category—it’s a life that is normal. After I pressed them, they expounded: normal life requires stability, always dependent on the stability of the state, which allows for raising, educating, and empowering children, as well as for an overall sense of progress. Normal life, my father clarified, also has nuances, and it’s improved (though the exact translation of the word he used would be beautified) with things like skiing, sports, singing, children, beekeeping, etc. At which point I realized that normal life was in fact the life they had before the war, what they had lost. Normal life is therefore simultaneously a nostalgic and utopian project, both irretrievable and unachievable.

All the married heiresses I have known have shipwrecked.

—Benjamin Disraeli, 1880Which is to say that normal life is delimited and defined by catastrophe—it’s the life ruptured, the life made both unavailable and visible by katastrofa. And, inversely, katastrofa is whatever ruptures life, what makes its stability, its necessary biological and emotional inertia, impossible. Much as catastrophe in tragedy necessitates the resolution of the plot, katastrofa necessitates a narrative of normal life, which we can perceive only through the catastrophic screen dividing our life into before and after.

As for me, I have a confession to make: my mind is linguistically obsessive, ever relentlessly and involuntarily generating wordplay and verbal distortions. There has to be a diagnosis related to that kind of constant chatter, or to the fact that, every day of my normal life, I talk to myself in Bosnian, usually in a voice of a Sarajevo street thug—cursing, threatening, insulting, mainly myself (or rather the part that is not a Sarajevo thug). Well, that language-obsessed mind has spontaneously come up with the name of Sergei Katastrofenko—an imaginary Slav, probably Ukrainian—who flickers as a possibility of a character, or a joke, or a catastrophe. The name Sergei Katastrofenko often bounces around my head as I scan the world for the ripples of disaster, even as he hasn’t quite acquired a full voice, let alone a body. But when he does acquire it—and when that happens, I’ll be losing my mind—he’ll become a perfect embodiment of katastrofa, of the idea that no reality—or the narrative of it—is possible without catastrophe.