To love a woman who scorns you is to lick honey from a thorn.

—Welsh proverb,Not About the Money

Sensuality is often mistakenly associated with prostitution and pornography, matters with which true sensual appreciation has only distant connections.

By William H. Gass

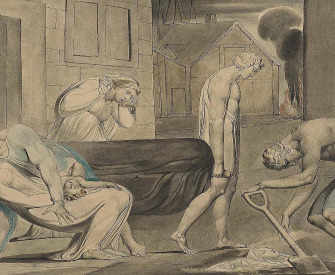

Three Lovers, by Théodore Géricault, 1817–20. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles.

Other people’s sensual experiences aren’t worth a straw.

—Louis Aragon, The Libertine

A few years ago I tried to lead my students through two brief novels by Colette, Chéri and The Last of Chéri. I thought, among other things, that these beautiful books would furnish us with a good opportunity to think about the nature of sensuality and its tense relationship to sex—which is a close but not always friendly sibling—and to love, which is often another matter altogether. At the very beginning of our trip, we halted in order to examine a string of pearls belonging to the reluctantly fading beauty, Léa de Lonval. She is a courtesan, as the French say, of a certain age and the sexual mentor of her present bed toy, the handsome Chéri, who has just picked the necklace from her dressing table and declared his desire to possess it. “Give them to me,” he says, “around my neck they look as well as they do around yours.” As the teasing becomes serious, we learn that there are as many pearls in this rope as years in their owner’s life, and that his request to wear them is symbolically the same as placing not only her history about his neck but also the weight and worries of his future years upon his youthful features. Indeed, his mistress immediately complains that when Chéri laughs, ugly wrinkles disfigure his nose.

The light in the room glistens from the chamber’s polished surfaces—the jewels, mirrors, Chéri’s grin, his Moorish slippers and silk pajamas, and particularly the whites of his black eyes—joining these rapid scintillations to those associated with Léa, especially with her naked arms only at that moment rising lazily from the interlaced sheets of her enormous wrought-iron and polished copper bed. He is a malicious imp, continuing to posture. “Il penchait sur la femme couchée un rire provocant qui montrait des dents toutes petites et l’envers mouillé de ses lèvres.” Janet Flanner translates: “He tossed toward the recumbent woman a provoking laugh which showed his small teeth and the soft inner sill of his lips,” the last phrase not quite Colette’s, who has written “the moist reverse” or “inside side of his lips.” Yet Flanner has fallen in with her text’s intention so perfectly that “sill” collects the signals sent into this sexually charged scene the way a fly can sometimes be caught by a quick fist.

My students understood, at this stage in the sexual war between these characters, that “Léa! Donne-le-moi ton collier de perles!” amounts metaphorically to the declaration, “I want your inheritance; I want your wealth, your refined tastes, your social suspicions tuned to every trick; I want everything except your wrinkles, your states of anxious self-regard, the face in your mirror.” In the world both lovers occupy, pearls are permanent; the neck not so much. Above all, these young readers believed—when Chéri accuses Léa of being afraid he’ll steal her necklace—that in the final sum, it’s all about the money, dummy. The lesson seems to be: if you are wise with its use, wealth will purchase social position, lovers, and the amusements needed to occupy an idle life.

But it is not the power of money that is truly captivating here; it is the sensuality of Chéri’s mouth. The sill is the soft, moist surface of the lip, rolled back from the pressure of another’s, and placed at the point where the slow, sensuous kiss begins. The length, width, curl, and stretch of the lips; their movements, moisture, and color all contribute to the expressive character of the mouth, then the face, and finally, to the person as a presence. In this blossoming process, the mouth shows its unique expressive quality as a body part. Breasts—items of much vulgar social focus—call attention only to themselves. Eyes become erotic rivals only in genteel novels where they flash, wink, weep, and gleam, like train signals at a crossing. But it is the mouth that always will be felt to be nearer our inner nature than the genitals because it is mainly the mouth, as Plato noted, through which the soul often chooses to show itself—to reveal or conceal who we are. Through it we communicate by shaping our exhalations into poufs, shouts, vowels, emphatic clicks, or extended hisses; and it is our mouth, customarily with our will’s permission, that refuses or admits food, wine, even air when we pant from pleasure, exertion, or a stuffy nose.

It has been frequently observed that a whore who will open her legs like a book with a cracked spine will refuse her customer’s kiss. In the movies the mouth is the measure of a couple’s passion, not the movement of their hips. For decades, no courtship could be carried on without a careful observance of the cigarette lighting ritual. He offers. She accepts, withdrawing the cig from its silver case, then positioning it to be lit, leaning toward him, eyes awake; he extends the flame. She draws it in. Both finally measure the amount of come-hither yet scornful smoke that will be blown in the beloved’s face.

We are not seriously engaged until we touch, until we taste the taste of our lover, one warmth warming itself with the warmth of another, before the shudder of the body signifies conclusion. Sex is friction, orgasm is spasm—an amusing and persuasive confusion of words. Then we explore our bodies as if we had never seen such countryside, and find that, like John Donne, we have the need and right to exclaim, “O my America! my new-found-land….”

Lazy by nature, we often call something sensuous just because it is a quality sensed—“I see blue. Is that good for you?” In that rather vapid usage, any shade could be suitably so-named, any noise or any odor deemed sensuous, not just some. After a bit of benevolent discussion we might affably agree, for the sake of the argument, that we have seven senses at the very least: for the visible, audible, odiferous and tactile; for the taste of sweet and sour; for local thermals, and that feeling of movement in the muscles said to be kinesthesia. These senses have different ranges, or distances of transmission, either due to their form of dispersal as signals or to the quality of our receptors.

I am, though, inclined to narrow the more general meanings of sensuality to deal with it in its secondary sense, as an evaluation. At this point we should be concerned with the quality of the experience; the saturation of a hue, its purity and consistency; with the way the sensation demands more and more of our attention, and entices us to repeat it: a bite of dark Belgian bitter chocolate, a solid that’s dissolving to form an exquisite puddle. As the chocolate coats the tongue it drives away all normal competition: what a friend is saying or what is showing on the screen. The feel of sand sifting through the fingers, the wail of a trumpet filtered by a forest, a softening soufflé—all participate in the moments of sensual transition. Such fleeting sensations struggle to realize themselves, and then they are felt to subside, with a shiver that is among the dearest of things.

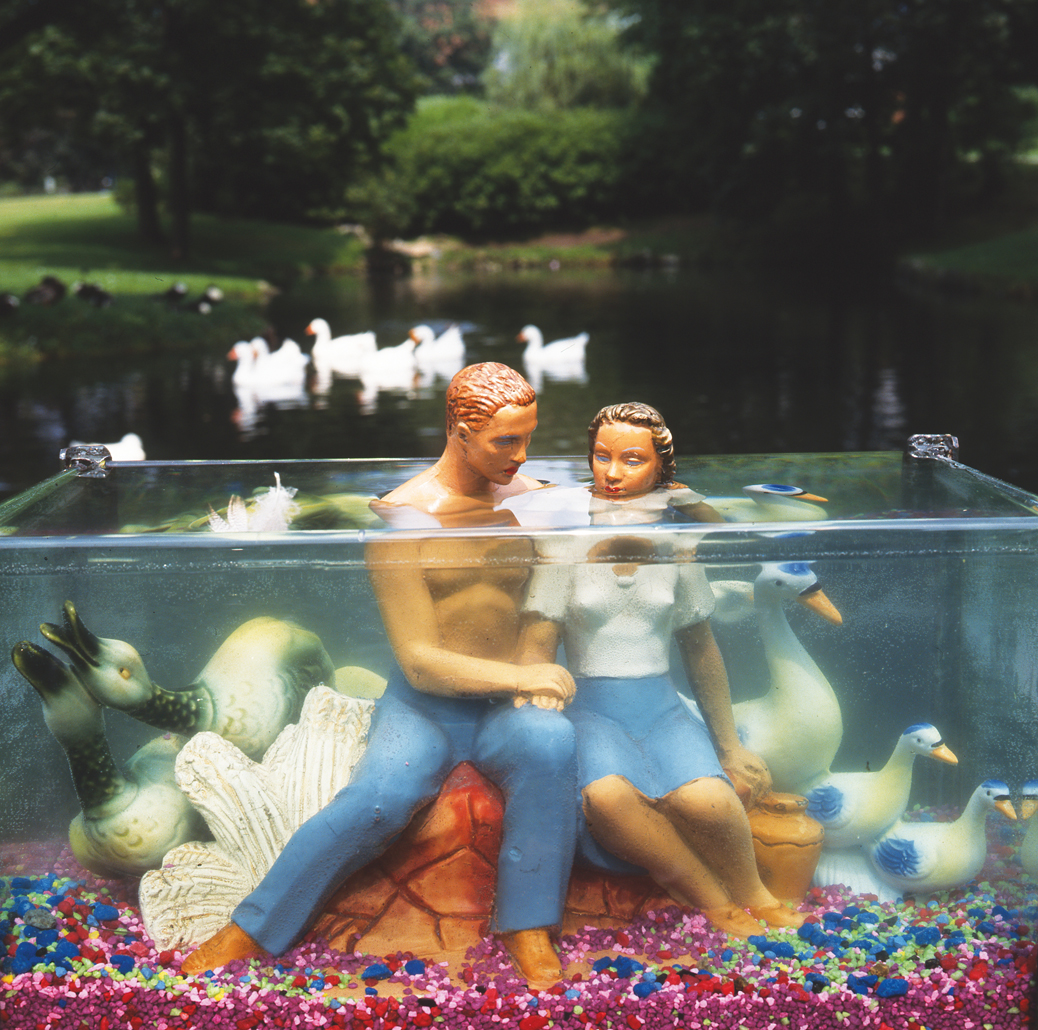

“Ducks and Lovers,” 2008. Photograph by Arthur Tress. © Arthur Tress, Courtesy ClampArt Gallery.

Far away from the sensual, from the leap of water into a stream or the flow of cascading hair in your hand, is the pornographic, the mechanical in-and-out that threatens to replace the former’s subtlety with its own blunt legibility. Porn is primarily a masturbation aid, and in that role also an enemy of sensuality. Porn, as has been frequently pointed out, is created principally for the penis, which is huge, untiring, and supremely confident. Every ejaculation is followed by a fresh paragraph. No utility likes to be accused of being slow in its operation. A good example of this fast-forward action is found in Bruce Hawkins’ Jupiter’s Passion: “Arnette wasted no time. He spread the bearded cunt mouth and immediately pulled Delara’s clitoris up to his mouth. I watched the pair gluttonize each other’s genitals. I listened with growing envy to the sloshing noises of their sex feasting.” Hard porn characteristically reduces any possible sensuality to its crudest level—hogs at the trough, corpses eaten eagerly. The hard porn flag should display its motto: “Arnette wasted no time.”

Porn rarely asks why it is that women wear the button when it is men who respond like a flashlight or complain that there’s not much to play with there either. Though it is hidden and hard to find, for porn it is as large as a nipple and sends signals to the fingers like a beacon. Porn customarily treats female desire as if it were male: the same interest in appearance and organ size (dainty, deeply furred, rosy-lipped), the same immediacy of response (swollen, wet, hot, aching), the same readiness to act, the same certainty of satisfaction (howling, screaming, thrashing, passing out). Buildup is achieved by the gradual introduction, into a compulsory series of sexual bouts, of increasingly disapproved methods of fleshy satisfaction—mainly, oral and anal—followed by the appearance of sadomasochistic, fetishistic, or homoerotic elements, and culminating in groups of sexual swingers set on multiplying the number of their interlocking parts. In the Marquis de Sade someone is always organizing the orgy by issuing what are really ludicrous instructions: “Count Z, you will stand in that corner bent over like a croquet hoop while Lady P lies beneath you and young Priscilla mounts a stepladder.” The possible combinations are so numerous that a checklist is necessary lest one lose track of the level of organization that has been reached.

Sensuality, in its praiseworthy meanings, prefers the circle not the line, or, better yet, the spiral—or better yet, the puddle. It regards lust as a lout who does not stroll but dithers about like the rabbit in Alice in Wonderland. Then, after a moment of demanding exercise, the fun is over: when the feverish eagerness of Before, indicated by Chéri’s strewn clothes, is replaced by the customary cigarette, or the awkwardness of getting trousered; by guilty gloom, malicious teasing (“Léa, give me your pearls”), the suddenly remembered assignation (lunch); or one of the many other surly disappointments of After.

Sensuality is often mistakenly associated with harlots and their customers. Most excesses of the senses—nymphomania, gluttony, wantonness, drug and alcohol abuse—are nailed to the same sign. However, mechanical repetition—hence habit, routine, and surfeit—are enemies of appreciation. The man who is commonly and incorrectly called a sensualist cares only what the object or activity does for him in terms of numbness, erotic readiness, or exhilaration. The true property of sensuality evident in the fineness of a wine or the peace that inhabits certain surroundings—though it belongs to its owner as firmly as vines to walls—remains a tertiary quality, inherently adverbial. It is the quality of a quality, and it depends on the perceiver for its existence as much as does the thing perceived.

Junichirō Tanizaki’s In Praise of Shadows beautifully sets down the conditions required for the reception of some kinds of sensuous experience and they occur, of all places, in the Japanese outhouse. Americans have rarely experienced the pleasures of the carefully appointed path from the farmhouse to the john, admittedly a cold stroll as Tanizaki says, “In winter there is always a danger that one might catch cold. But as the poet Saitō Ryokū has said, ‘elegance is frigid.’” He further shows how this activity provides the necessities for sensual meditation:

There are certain prerequisites: a degree of dimness, absolute cleanliness, and quiet so complete one can hear the hum of a mosquito. I love to listen from such a toilet to the sound of softly falling rain, especially if it is a toilet of the Kanto region, with its long, narrow windows at floor level; there one can listen with such a sense of intimacy to the raindrops falling from the eaves and the trees, seeping into the earth as they wash over the base of a stone lantern and freshen the moss about the stepping stones.

The passage is sensual, not merely descriptive of it, even in translation, because the author’s understanding is in the service of perception’s most discriminating qualities. He frames the Kantō area and zooms in on it with the precision of a telephoto lens. It’s as if Tanizaki were referring to the soil of some wine-growing region, coupled with his choice of ordinary annoyances—water drip, mosquito hum—and then, with one swift stroke, turns lead into gold. The prose follows the route of the rain as it journeys back from the john toward the house: from eaves to earth, earth to moss, moss to stepping stones.

Although the sensual is an experience of intense satisfaction and approval, it is not competitive. Things seen or touched or tasted this way are what they are: a red so saturated with its hue it mesmerizes the eye, an insect slowly rubbing together legs as thin as a line, a cottonwood puff lighting on a blade of grass, the trail of a finger across a thigh, the union of two voices through a series of compelling notes. The sensualist treats qualities as terms, not as relations. He gathers up relationships into entireties, not like a handful of straw but like the thatch of a hat.

Lord! I wonder what fool it was that first invented kissing.

—Jonathan Swift, 1738A loving gesture stands to a preprogrammed pleasure the way an instance of wit stands to a joke. Like a play of wit, the sensuality that I am admiring here arises from a specific cause, is not readily repeatable, and reflects its uniqueness. Masturbatory fantasies, on the other hand, quickly establish themselves and can be carried about in the head like a volume of funny sayings for all occasions. The moment you set out to have a particular sensual experience you become a sensualist according to the popular definition. But the first-grade sensualist is rarely a success; he becomes desperate and soon seeks insensibility instead. Aristotle helps us to believe that happiness arises when virtuous activities are performed for their own sake. Similarly, lovemaking (a phrase from the Christmas-cookie kitchen) loses its genuineness when it keeps faithfully to a schedule—now the toe, now the nipple, next the clit—moving like a train between stations. Books of sexual instruction are not like cookbooks, because the ingredients and times and amounts of one’s sex life do and ought to vary, with the result that the motions of stirring and whipping, simmering and stewing, constantly carry a different message to the anticipated dish.

Beyond a certain stretch, then, sensuality is biologically bad business. The sensualist is the window-shopper, a flâneur, one who savors the dry spoon before the soup is even served: he is a slow, ruminative eater; she likes to close both eyes to listen to the song without distraction. Léa would dawdle out the hours, move no more swiftly than syrup. When asked whether she shall go to lunch at a familiar haunt that day, Léa replies, “Not I. I’m off duty. I’ll go drink coffee at two-thirty—or tea at six—or have a cigarette at quarter to eight.” Chéri lives like a train in transit, always announcing the next station. And my students were inclined to follow his lead. The future consumed them. It could never come fast enough. They knew, and felt smug because they knew that it was all about the money, dummy.

Léa is schooling Chéri in the arts of love, or rather, in the skills of sensuality, because the true arts of love have to do with acts of consideration and concern for the security, freedom, and happiness of others, and these benevolences are matters with which sensuality has only distant connections. We may find ourselves in an intimate embrace for numerous, sometimes overlapping, reasons: because we want to practice position thirty; because we are being well paid for the humiliation; we desire a child and the kingdom needs an heir; our partner will shower us with favors including strings of pearls; the both of us need the comforting sense, like cooperating politicians, of being in bed together; it is what we do once every week as well as watering the plants; because we need to reassure one another that we are still desirable or that the damn deed of darkness can still be done. The same caress may be saying many different things too: I am touching you this way so you will touch me another, and then we shall find release from these tensions together; or, I am touching you this way so that you will be assured of my continued concern; or, I am touching you this way because it gives us both abundant pleasure... perhaps abundant for both of us because it means our quarrel is over. The permutations outrun mathematics: abundant because the betrayed wife—grown cold—doesn’t like being useful to him any more; abundant because the betraying husband always asks for it, and she relishes the chance to deny him something he wants; abundant because the mistress is meanwhile getting even with three other lovers. Vindictive pleasures have a nice, tart sauce.

The sensualist is enamored of her own consciousness, awake or dreaming, because only when we are conscious are we alive. Unconscious, we become a corpse that still devours air, and then despoils it. Consciousness remains a philosophical mystery after lo, these many years—yet it is what we directly know of our inner self, and all we can immediately perceive of the world outside. Sensuality extols sensation. So to revel in the quality of our consciousness is to value the quality of life. But these revelations of in or out of doors are not confined to properties like tastes, colors, sounds: the grace of a movement, the turn of a phrase, the depth and richness of an emotion’s symptoms or desire’s drive—the blushes of love, sighs of relief, of thanksgiving; a certain buoyancy of being—all can possess that state of being we call sensuality. What other use is there for skipping if not to use up a joyous excess of energy by feeding it to the limbs?

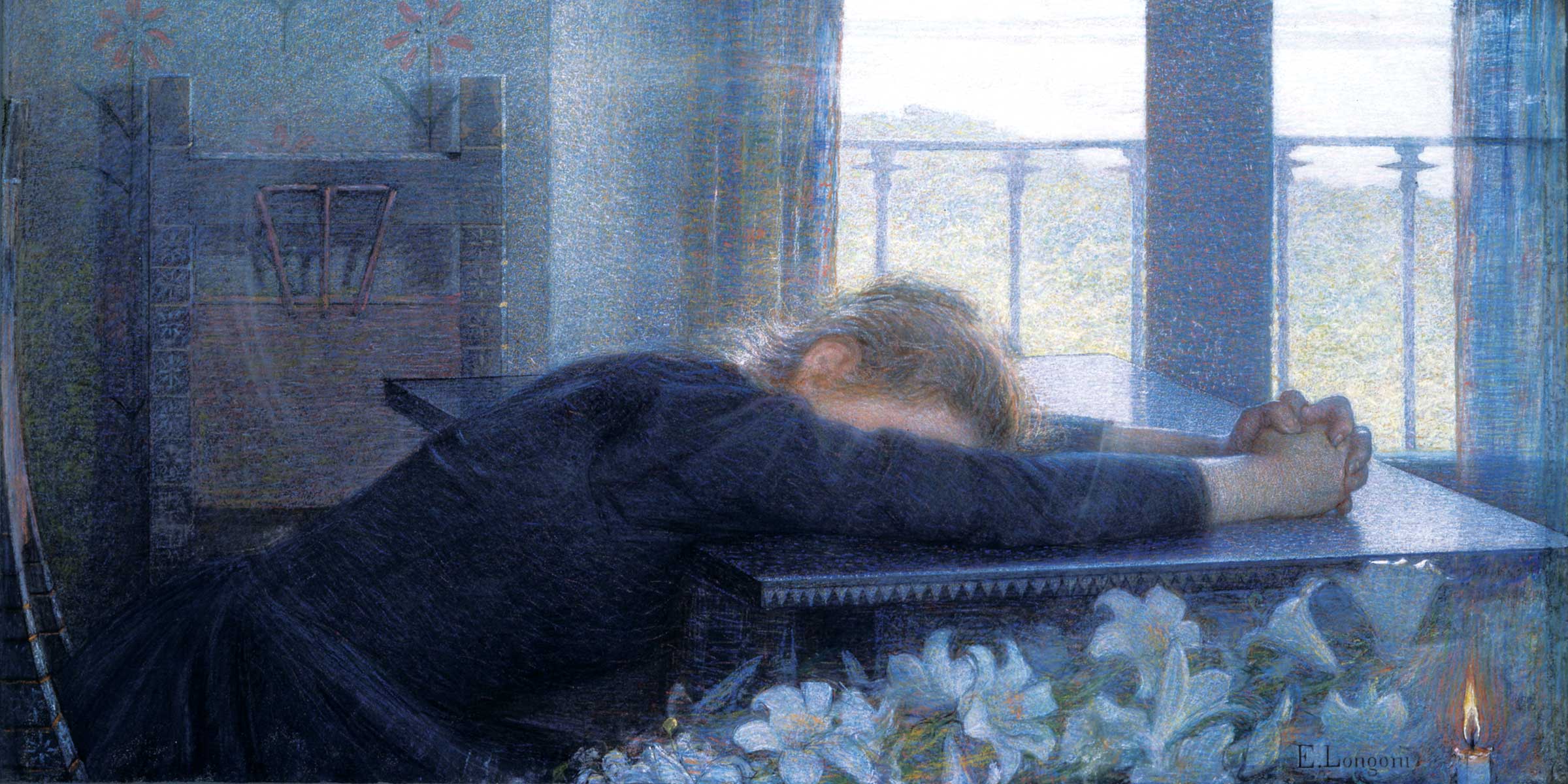

Alone! (detail), by Emilio Longoni, 1900. © Alinari Archives/Art Resource, NY.

Of course, consciousness is composed of far more than the simple sensations or impressions of David Hume. Thoughts, feelings, desires, daydreams, memories, vivid expectations, as well as our sensory freight, serve as the beginning of a crude list. Thus we and the world are revealed to one another, and in what a tangle! Until Henri Matisse picks up a brush alive with red. A dancer’s figure may be as directly seen as the face of a friend, but what about the awareness and appreciation of their beauty? Perhaps it is because we have been educated in admiration, but don’t we see and aren’t we pleased simultaneously? Aren’t our perceptions and our approvals inextricably linked? Don’t we read the meaning of the movement with the same immediacy, or understand the intimacy suggested by Chéri’s inviting sill-shaped lower lip?

We do not bring an innocent eye to Michael Eastman’s Rodins, to cite a nearby instance. We know how fiercely the sculptor was scolded for his excessively modeled surfaces and about his habit of allowing figures to emerge from their materials as if the stone itself were giving birth. He animated every inch and orifice, giving it its own sense of life, so an entire head would be expressive. Yet we also know that these pieces do not look quite this way in their place of display in the Hôtel Biron. Only in Eastman’s marvelous photograph—in his transformation of detail into a fresh whole—can we feel the weight of those planted feet upon the mud that oozes through the toes and away from the foot, wet with light, like some of history’s reluctant consequences.

To encounter Immanuel Kant here may be like finding a china bull in a chop shop; nevertheless his formulation for the aesthetic is everywhere more than apt. Like the saber hanging on the wall in its scabbard, he defined the aesthetic experience as that of purposiveness without purpose—either in the look of a utility that has been retired or in an accidental object that seems rationally shaped to perform an undefined task. It is an experience that is not mediated by concepts, so that we do not simply look at Eastman’s photographic interpretation of Auguste Rodin’s Age of Bronze and cry out, “Muddy feet!” Moreover, it views things with disinterested interest, so that we do not admire this marvelously presented museum piece and wonder if the right answer on the quiz is Rodin. The sensuous quality of an experience is never about the money, honey.

We are all passersby for those who pass us. We are all voices in the crowd, strangers together at the races or the opera; but to have a body that another body longs for, and another self desires, or to have made a work of art that is as much welcomed as a lover’s breath at your breast—these are among the truly important things of life. Your work is of special value when it is more prized, more frequently embraced, more vividly remembered, more wholly admired, than you are. But your body? Not for so much or so long.

The sensualist cries out, “Stay a bit, my tongue has not concluded its encounter; wait a moment for my smile to widen.” If the sensualist could, he would stretch time like a length of elastic. Nothing does that like the camera. The movie actress who is told she will be naked only for a moment in her shower scene had better remember that uncounted millions of men now have freeze buttons for fingertips, so that her breasts might as well be bronzed and her figure stood on the steps of a library instead of the lion. The camera halts a habit in mid-blink, catches the flutter of a few leaves in a startled spurl, cuts into milliseconds an expression that was in transit from grief to rage, then pins them like bugs in a frame. There are so many occasions in life that are scarcely seen, let alone savored, because the moments have made themselves as small and still as a bee asleep in a bloom, or have no more wish to endure than dew on a leaf, so before you know it they have become other than they were, as Heraclitus claimed. But experience is not simply a river you can’t step into twice: it is composed of unrebreathable sighs; it is a lemon that comes sliced; it is a fall of light upon a dusty table, a sausage three millimeters from its intended mouth. Though they are deeply meant, wishes—“wait”—“stay”—“cohere”—cannot change fate... even the glacier, as slow as it goes... goes.

Compared to the rich sensory material other arts have available to them, literature must go in rags and especially in tatters. Despite their lovely lilt, one cannot say, “Pass the Alabama,” or, “I love Louisiana,” many times in one day, and our characters haven’t Arabic’s chance to look good in anything it puts on. A line of the Qu’ran can embellish a Moorish wall even for eyes that understand nothing of what it says. We decorate ours with the names of those who have fallen in our foolish wars—a pitiful claim on distinction. Nevertheless, sound is a major musical net in the capture of sensuous qualities. We can begin to install those qualities by naming things taken to be redolent in the referential world, realizing that “blue” is as abstract a term at this stage of its life as “transubstantiation.”

Youth Between Vice and Virtue, by Paolo Veronese, c. 1581. Prado Museum, Madrid, Spain.

Yes, a style, an art, should make you see, as Joseph Conrad said. “Regarde” was Colette’s command. But it should have energy (which stands in for desire), understanding (which is represented by form or the play of mind), feeling (of which there are so many kinds), memory (the second kiss remembers the first), and imagination (the wings of the dove, the sill of the lips). It is the death of any of these elements—particularly sensuality—when the organs that fuel it are chaotically crowded with stimuli as if you were dodging signs, sounds, and pedestrians in the Ginza, or being punished by a rock concert and its cavorting kids, or furious with your government, or overcome by guilty memories. Where shame, noise, confusion, outrage are in command, serenity or any secure enjoyment is impossible.

One of the best illustrations of the serenity and secure enjoyment is in D.H. Lawrence’s Twilight in Italy. It is an example of the sensual that has never disappointed me. I return to it again and again for solace when the language seems everywhere to be sustaining mortal damage. Lawrence joins repetition to rhythm and moves his words along with a music perfectly attuned to the monk’s stride:

A cricket hopped near me. Then I remembered that it was Saturday afternoon, when a strange suspension comes over the world. And then, just below me, I saw two monks walking in their garden between the naked, bony vines, walking in their wintry garden of bony vines and olive trees, their brown cassocks passing between the brown vine-stocks, their head bare to the sunshine, sometimes a glint of light as their feet strode from under their skirts.

It was so still, everything so perfectly suspended, that I felt them talking. They marched with the particular march of monks, a long, loping stride, their heads together, their skirts swaying slowly, two brown monks with hidden hands, sliding under the bony vines and beside the cabbages, their heads always together in hidden converse. They did not touch each other, nor gesticulate as they walked. There was no motion save the long, furtive stride and the heads leaning together. Yet there was an eagerness in their conversation. Almost like shadow-creatures ventured out of their cold, obscure element, they went backwards and forwards in their wintry garden, thinking no one could see them.

He can follow them only in spirit, but these “two brown monks with hidden hands” seem up to something. He has no idea what, except his sentences suggest that the hands beneath their skirts are touching though they do not touch, that their heads are resting upon one another though they do not rest, that their intercourse is intimate and deeply confidential, and is paragraphed by their joint passage up and down a garden which winter has stripped of grape and olive leaves till it is skeletal and shorn. In such surroundings only they are clothed, only they converse, only they move back and forth between the cabbages under a cold sun. How beautifully Lawrence has seen his scene, and how remarkably he has felt the monks’ secrecy, their intimacy, their “inaudible undertone.” Only one word gives his concerns away. In the silence that winter has conferred, they move like shadows that have come to pay their respects to the residents of a cemetery, their strides are decisive but they are going nowhere; their strides are also furtive—their privacy, their union, its safety, assumed.

Sensuality, I suppose, always has to do with someone’s flesh, some dear eatable, some fascinating surface, some arresting sound. And the softness of soft skin is often softness enough. Then we dwindle to our finger’s tip as if there were nothing else alive, while consciousness makes a meadow of the moment; but the senses celebrate themselves best when they rejoin the other functions of awareness. To be too full of sensation is to be like a cup made of its own drink—a miracle—but impossible to hold. Nor can Lawrence sustain his depiction of the two monks and their solemn pacing. For an instant he has stood outside himself. Then he seeks more ecstasy than they can serve up, and mostly what the prose shows is the strain such an aim puts on his resources. Nevertheless, Lawrence is not through. Twilight is his theme and so he pulls down darkness like a drape. Snow on the far off mountains turns in the twilight the color of a rose: “And I noticed that up above the snow, frail in the bluish sky, a frail moon had put forth, like a thin, scalloped film of ice floated out on the slow current of the coming night. And a bell sounded.” This sentence is perhaps a metaphor too fully explained, but now we are no longer dealing with sensation. When the bell sounded it was not for the monks alone to hear, but for the ship of ice the moon had momentarily become to heed. However, the imagination is another subject. Louis Aragon was wrong to be indifferent to the sensual experiences of others. What would we do without Rodin’s models, whose flanks have yielded us such pleasure, or Colette’s French savor of fruit and flesh, or Lawrence’s chaste monks in decorous conversation through winter’s bare garden beneath a cold, chaste moon?