“My dearest—

One who so holds you, one who will not have

a dearest, if not you, now sends you this,

who cannot, out of shame, reveal herself,

but if you wish to know what I desire,

it is that, nameless, I might plead my case

unrecognized as Byblis, undiscovered

until my wish were certain to be granted.

“You might have sensed I was in love with you

from my drained complexion and stressed countenance,

my eyes so often filling up with tears,

the sighs brought on by no apparent cause,

my constant need to throw my arms about you—

and, if by any chance you noticed them,

the kisses that were more than sisterly.

“And yet, despite the burden of my wound,

despite the fury of that inner fire,

I did my best—the gods will witness this!—

to bring myself again to sanity;

unfortunate, I’ve struggled for so long

to get away from Cupid’s fierce encounters,

enduring more—I think you would agree—

than any girl could bear.

“Now overwhelmed

by my great passion and compelled to speak,

I seek your help with this fainthearted prayer,

for you will be my rescue—or my ruin:

the choice is yours and you must make it now.

“I pray to you not as an enemy,

but as the one most closely joined to you,

who yet desires to be nearer still,

more closely linked by even stricter chains.

“Let old men know what is and is not proper,

distinguish ‘decent’ from ‘indecencies,’

and keep the fine distinctions of the law.

Heedless passion accords with our youth.

We have not learned yet what may be allowed,

so we believe that everything may be,

and follow the example of the gods!

“In our case, we haven’t a strict father

or a concern for what the people say,

or fear to serve as an impediment;

and should there be occasion for our fear,

our pleasurable thefts will be concealed

by our relationship—for as your sister,

I am allowed to speak with you in private,

and openly embrace and give you kisses.

“The little that is lacking—is it too much?

Have pity, then, on one who speaks her love

but would not speak unless compelled by passion;

and let it not be written on my stone

that by refusing me, you caused my death.”

When she had finished setting down these words

on tablets which were filled right to their edges

she sealed the wicked missive with her signet,

dampened—her mouth was dry—by flowing tears.

Shamefaced, she called a servant to her side

and gave him orders in a shaky voice:

“Take these, most faithful one, to our—”

and after a long pause, she got out,

“—brother.”

© 2004 by Charles Martin. Used with permission of the publisher, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.

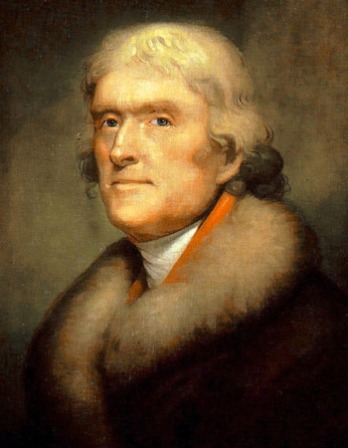

From Metamorphoses. Ovid announces his poem’s purpose in the opening lines: “My mind leads me to speak now of forms changed/into new bodies.” He proceeds to tell some 250 stories of transformation, among them this tale of Byblis who fell in love with her brother Caunus. Ovid attributed his exile to the Black Sea by Emperor Augustus to “a poem and a mistake”—the former his Ars Amatoria, the latter perhaps his knowledge of the indiscretions of the emperor’s granddaughter. The poet’s books were ordered to be removed from Roman libraries.

Back to Issue