Liberty, or freedom, signifies properly the absence of opposition—by opposition I mean external impediments of motion—and may be applied no less to irrational and inanimate creatures than to rational. For whatsoever is so tied or environed as it cannot move but within a certain space, which space is determined by the opposition of some external body, we say it has not liberty to go farther.

And so of all living creatures while they are imprisoned or restrained with walls or chains, and of the water while it is kept in by banks or vessels that otherwise would spread itself into a larger space, we say they are not at liberty to move in such manner as without those external impediments they would. But when the impediment of motion is in the constitution of the thing itself, we do not say it wants the liberty but the power to move—as when a stone lies still or a man is fastened to his bed by sickness.

And according to this proper and generally received meaning of the word, a freeman is he that in those things which by his strength and wit he is able to do is not hindered to do what he has a will to. But when the words free and liberty are applied to anything but bodies, they are abused, for that which is not subject to motion is not subject to impediment; therefore, when it is said, for example, the way is free, no liberty of the way is signified but of those that walk in it without stop. And when we say a gift is free, there is not meant any liberty of the gift but of the giver that was not bound by any law or covenant to give it. So when we speak freely, it is not the liberty of voice or pronunciation but of the man, whom no law has obliged to speak otherwise than he did. Lastly, from the use of the word free will, no liberty can be inferred of the will, desire, or inclination but the liberty of the man, which consists in this: that he finds no stop in doing what he has the will, desire, or inclination to do.

Fear and liberty are consistent, as when a man throws his goods into the sea for fear the ship should sink—he does it nevertheless very willingly, and may refuse to do it if he will. It is therefore the action of one that was free; so a man sometimes pays his debt only for fear of imprisonment, which, because nobody hindered him from detaining, was the action of a man at liberty. And generally all actions which men do in commonwealths for fear of the law are actions which the doers had liberty to omit.

Liberty and necessity are consistent, as in the water that has not only liberty but a necessity of descending by the channel; so likewise in the actions which men voluntarily do, which, because they proceed from their will, proceed from liberty, and yet—because every act of man’s will and every desire and inclination proceeds from some cause, and that from another cause, in a continual chain whose first link is in the hand of God, the first of all causes—proceed from necessity. So that to him that could see the connection of those causes the necessity of all men’s voluntary actions would appear manifest. And therefore God, who sees and disposes all things, sees also that the liberty of man in doing what he will is accompanied with the necessity of doing that which God wills, and no more nor less. For though men may do many things which God does not command, nor is therefore author of them, yet they can have no passion nor appetite to anything of which appetite God’s will is not the cause. And did not his will assure the necessity of man’s will, and consequently of all that on man’s will depends, the liberty of men would be a contradiction and impediment to the omnipotence and liberty of God. And this shall suffice as to the matter in hand, of that natural liberty which only is properly called liberty.

From Leviathan. The son of a clergyman in Wiltshire, Hobbes studied at the University of Oxford before becoming a tutor to William Cavendish, a future earl of Devonshire. Hobbes fled England in 1640, fearing persecution for his royalist sympathies, and lived in Paris for eleven years. Leviathan has been read as an endorsement of Charles I’s decision to reign for eleven years without ever convening Parliament. The book was later investigated by a House of Commons committee, after which Hobbes burned many of his papers.

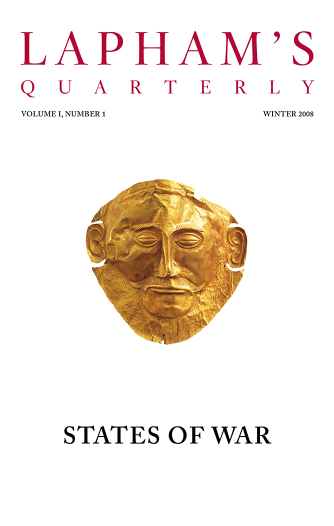

Back to Issue