Real generosity toward the future lies in giving all to the present.

—Albert Camus, 1951School Ties

Booker T. Washington laments the state of Southern schools.

There is a great lack of money with which to carry on the educational work in the South. I was in a county in a Southern state not long ago where there are some thirty thousand colored people and about seven thousand whites. In this county not a single public school for Negroes had been open that year longer than three months; not a single colored teacher had been paid more than fifteen dollars per month for his teaching. Not one of these schools was taught in a building that was worthy of the name of schoolhouse. In this county the state or public authorities do not own a single dollar’s worth of school property—not a schoolhouse, a blackboard, or a piece of crayon. Each colored child had had spent on him that year for his education about fifty cents, while each child in New York or Massachusetts had had spent on him that year for education not far from twenty dollars. And yet each citizen of this county is expected to share the burdens and privileges of our democratic form of government just as intelligently and conscientiously as the citizens of New York or Boston. A vote in this county means as much to the nation as a vote in the city of Boston. Crime in this county is as truly an arrow aimed at the heart of the government as a crime committed in the streets of Boston.

A single schoolhouse built this year in a town near Boston to shelter about three hundred pupils cost more for building alone than is spent yearly for the education, including buildings, apparatus, teachers, for the whole colored school population of Alabama. The commissioner of education for the state of Georgia not long ago reported to the state legislature that in that state there were 200,000 children that had entered no school the year past and 100,000 more who were at school but a few days, making practically 300,000 children between six and eighteen years of age that are growing up in ignorance in one Southern state alone. The same report stated that outside of the cities and towns, while the average number of schoolhouses in a county was sixty, all of these sixty schoolhouses were worth in lump less than $2,000, and the report further added that many of the schoolhouses in Georgia were not fit for horse stables. I am glad to say, however, that vast improvement over this condition is being made in Georgia under the inspired leadership of State Commissioner Glenn, and in Alabama under the no less zealous leadership of Commissioner Abercrombie.

Until there is industrial independence, it is hardly possible to have good living and a pure ballot in the country districts. In these states it is safe to say that not more than one black man in twenty owns the land he cultivates. Where so large a proportion of a people are dependent, live in other people’s houses, eat other people’s food, and wear clothes they have not paid for, it is pretty hard to expect them to live fairly and vote honestly.

The longer I live and the more I study the question, the more I am convinced that it is not so much a problem as to what the white man will do with the Negro as what the Negro will do with the white man and his civilization. In considering this side of the subject, I thank God that I have grown to the point where I can sympathize with a white man as much as I can sympathize with a black man. I have grown to the point where I can sympathize with a Southern white man as much as I can sympathize with a Northern white man.

As bearing upon the future of our civilization, I ask of the North what of their white brethren in the South—those who have suffered and are still suffering the consequences of American slavery, for which both North and South were responsible? Those of the great and prosperous North still owe to their less fortunate brethren of the Caucasian race in the South, not less than to themselves, a serious and uncompleted duty. What was the task the North asked the South to perform? Returning to their destitute homes after years of war to face blasted hopes, devastation, a shattered industrial system, they asked them to add to their own burdens that of preparing in education, politics, and economics, in a few short years, for citizenship, four million former slaves. That the South, staggering under the burden, made blunders, and that in a measure there has been disappointment, no one need be surprised. The educators, the statesmen, the philanthropists, have imperfectly comprehended their duty toward the millions of poor whites in the South who were buffeted for two hundred years between slavery and freedom, between civilization and degradation, who were disregarded by both master and slave. It needs no prophet to tell the character of our future civilization when the poor white boy in the country districts of the South receives one dollar’s worth of education and the boy of the same class in the North twenty dollar’s worth; when one never enters a reading room or library and the other has reading rooms and libraries in every ward and town; when one hears lectures and sermons once in two months and the other can hear a lecture or a sermon every day in the year.

The time has come, it seems to me, when in this matter we should rise above party or race or sectionalism into the region of duty of man to man, of citizen to citizen, of Christian to Christian; and if the Negro, who has been oppressed and denied his rights in a Christian land, can help the whites of the North and South to rise, can be the inspiration of their rising into this atmosphere of generous Christian brotherhood and self-forgetfulness, he will see in it a recompense for all that he has suffered in the past.

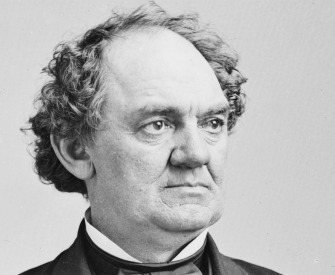

Booker T. Washington

From The Future of the American Negro. In 1881 at the age of twenty-five, Washington became head of the upstart Tuskegee Normal and Industrial Institute; when he died thirty-four years later, the school boasted an endowment of approxiametly two million dollars. Emphasizing the importance for blacks to first gain financial security, he said: “In all things that are purely social we can be separate as the fingers, yet one as the hand in all things essential to mutual progress.”