The Fortune whose temple is near the Tiber is called Fortis (that is, strong or valiant or manly), for having the power to conquer everything. Her temple is built in the gardens bequeathed by Caesar to the people, because the people believed he also reached his most exalted position through good fortune, as he himself has said.

I would hesitate to say that Gaius Caesar was raised to his most exalted position by good fortune had he not himself testified to it. When he left Brundisium in pursuit of Pompey on the fourth of January—though it was still winter—he crossed the sea in safety, because Fortune postponed the season. But when he found that Pompey had a compact and numerous army on land and a large fleet at sea and was well entrenched with all his forces—while he himself had a force many times smaller—Caesar had the courage to board a small boat and put out to sea in the guise of a servant, unrecognized by captain and pilot. Seeing the pilot change his course because of the violence of the waves, which hindered sailing out of the mouth of the river, Caesar took off his cloak and revealed himself. “Go on, sir,” he said, “be brave and fear nothing! Entrust your sails to Fortune and receive her breeze, because you bear Caesar and Caesar’s fortune.” He was confident that Fortune accompanied him on his voyages, travels, campaigns, and commands. Fortune would calm the sea, give warmth to winter, and grant speed to the slowest of men and courage to the most dispirited. What’s even more incredible than this, Caesar believed Fortune put Pompey to flight and gave Ptolemy the chance to murder his guest, so that Pompey would fall and Caesar would be innocent.

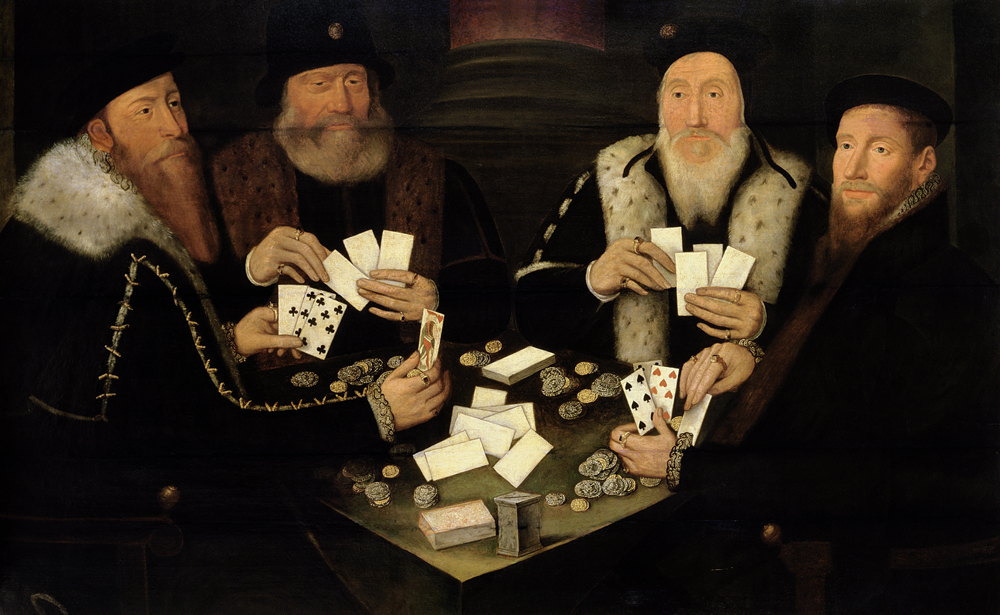

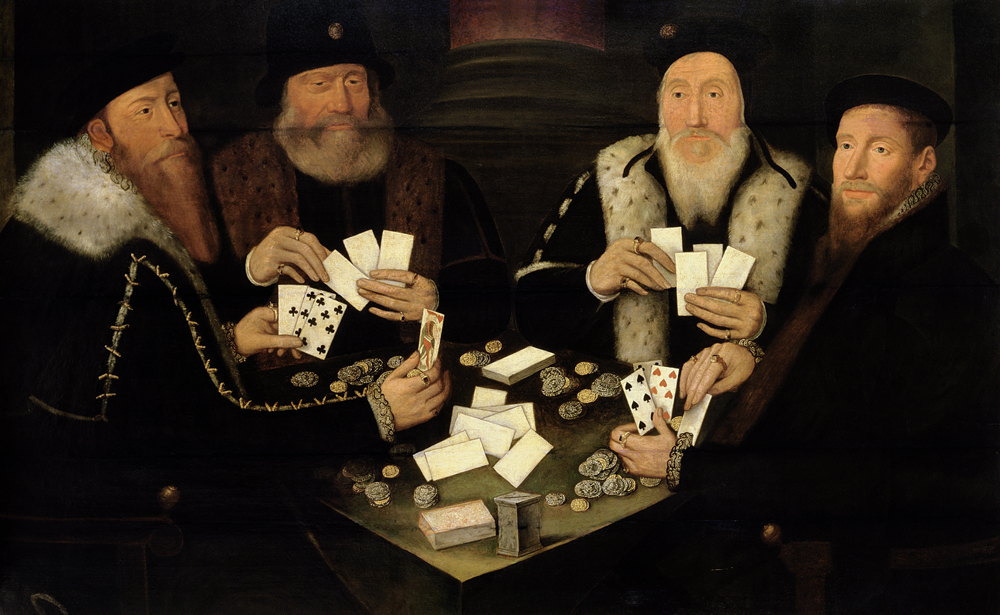

Four Gentlemen of High Rank Playing Primero, by the Master of the Countess of Warwick, c. 1568. The painting is thought to depict Francis Walsingham, William Cecil, Henry Carey, and Walter Raleigh. © The Right Hon. Earl of Derby / Bridgeman Images.

What then? Caesar’s son, Augustus, when he was sending forth his grandson to war, did he not pray to the gods to bestow on the young man the courage of Scipio, the popularity of Pompey, and his own fortune? He counted Fortune as the creator of himself, as if he were inscribing the artist’s name on a great monument. Fortune imposed him upon Cicero, Lepidus, Pansa, Hirtius, and Mark Antony. By their displays of valor, their deeds, victories, fleets, wars, and armies, Fortune raised him to be the first of Roman citizens. She cast down these men, through whom he had mounted, and left him to rule alone.

It was, in fact, for him that Cicero governed the state, that Lepidus commanded armies, that Pansa conquered, that Hirtius fell, that Antony played the wanton. Even Cleopatra was part of Caesar’s fortune, on whom, as on a reef, even so great a commander as Antony was wrecked and crushed so Caesar would rule alone. It is said that when there was much familiarity and intimacy between Caesar and Antony, they often spent their leisure playing ball or dice or watching fights of pet birds, such as quails or cocks. Antony always retired from the field defeated. It is further related that one of Antony’s friends, who prided himself on his knowledge of divination, often admonished him, “Sir, what business have you with this youth? Avoid him! Your repute is greater, you are older. You govern more men, you have fought in wars, you excel in experience. But your guardian spirit fears this man’s spirit. Your fortune is mighty by herself, but abases herself before his. Unless you keep far away from him, your fortune will depart and go over to him.”

But enough! The cause of Fortune is supported by the testimonies of these men.

From the Moralia. Born in Boeotia, educated in Athens, and made a priest in Delphi, Plutarch wrote, according to an index supposedly compiled by one of his sons, 227 works; among them is Parallel Lives, a source for several plays by William Shakespeare. Caesar’s relationship to fortune was a popular topic for Roman historians: in his Civil Wars, Appian referred to him as “a man who was extremely lucky in everything” and a believer “not so much in strategy as in daring and good luck.”

Back to Issue