Cat statue intended to contain a mummified cat, c. 300 bc. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Harris Brisbane Dick Fund, 1956.

The Keswick Museum and Art Gallery in northwest England has many items you’d expect: documents from William Wordsworth’s trudges through the Lake District, local prehistoric axes, and paintings of the surrounding hills and the artists who climbed them. It also has a historical curiosity you might not even know to expect: a “naturally mummified” cat that died seven hundred years ago. Discovered in the 1840s between the slates and plaster of a church roof about twenty miles east of Keswick, the dessicated feline lies on its side in a red-velvet-lined display case with a wooden frame, a handwritten note under its right hind leg describing its origin.

As mummies tend to be, it’s a rather horrifying display of paper-thin flesh barely hanging on to the bone, the mouth in a permanent snarl with a few errant whiskers remaining on its lip. And this cat is nowhere close to a unique specimen.

Dried cats (as they’re officially termed) can be found in a number of small museums in the British countryside. Often not discovered until hundreds of years after their deaths, they have been naturally preserved and mummified due to the lack of oxygen in the roofs, walls, and floorboards of the churches, private houses, and government buildings where they were buried. Every once in a while, homeowners will still find a dried cat while remodeling an old house.

Someone put dead cats in these walls, but to what end?

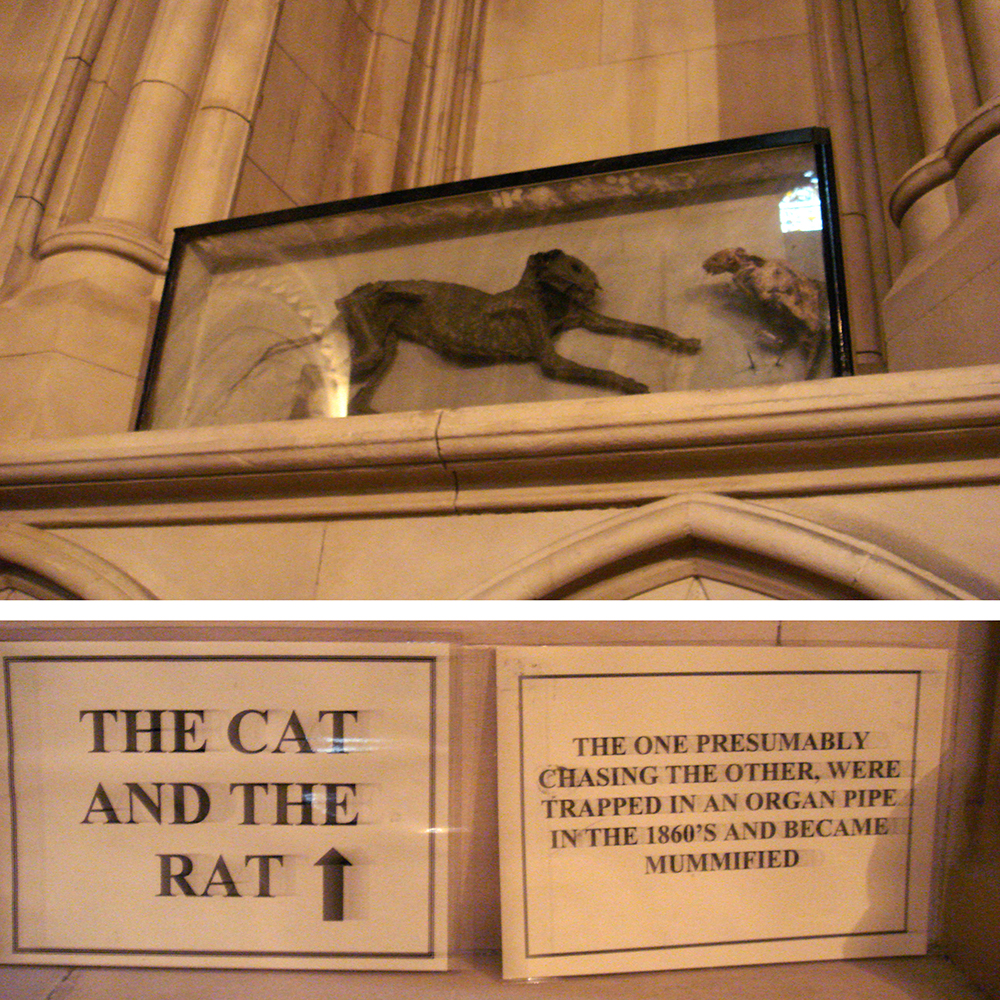

British archaeologist Margaret M. Howard conducted what is often cited as the definitive research on the phenomenon of dried cats, collected in a 1951 paper in the journal Man, published by the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland. Her observations were based on twenty-five separate specimens found in the United Kingdom, Ireland, Sweden, and as far south as Gibraltar. People have found dried cats in structures spanning the socioeconomic spectrum: the thatch of village cottages; in former pubs, stables, and schools; behind an organ at a cathedral in Dublin; and at the Duke of Bedford’s Bloomsbury Estate in London. They were found in two buildings designed by one of the most acclaimed architects in British history, Christopher Wren—one of them in the Tower of London.

Whatever their initial purpose—whether to scare away rats or protect the house from witches—dried cats soon evolved into an all-encompassing good-luck charm. The tradition of burying dead cats in new buildings migrated out of the European continent with British colonialism to the U.S. (mostly the Mid-Atlantic region) and even to Australia. (Workers renovating the historic John Carlyle House in Alexandria, Virginia, in the 1970s uncovered a dried cat bricked up into the foundation of the chimney, accompanied by sprigs of rosemary—an herb with a long history of uses in folk medicine.) The cats have also been found in France, Germany, and elsewhere throughout Europe.

Howard puts forward three hypotheses about the cats:

(a) that the cats were placed in buildings as foundation sacrifices

(b) that they were intended as vermin-scares

(c) that they were accidentally enclosed or trapped in cavities between walls, beneath floorboards, etc.

She concludes that the truth likely lies in a combination of the first two theories. The number of dried cats found, as well as the poses of many of them, point to a definitive intentionality on the part of humans building and occupying the space. Of course, the mummies are so old by the time they’re found that it’s hard to tell how the cats died, but all were dead before being interred. (In other words, there are no signs of struggle.)

We still have much to learn about dried cats, but there are a few things we can infer as to their significance in folk culture. In terms of the cats’ theorized role as the scarecrows of the wall, roof, and floor cavity, the logic lies in the fact that cats have always been used as mousers. (In the tenth century, Hywel Dda, Prince of Wales, passed laws to ensure the protection of cats, as they were so useful as a form of natural pest control.) Among the discovered dried cats, six were positioned with mummified rats in their jaws and chasing mummified birds. Howard writes,

It is difficult to imagine the reason for such elaborately arranged groups, which must have taken time and trouble to prepare, but it may have been felt that a cat with one or more rats in its clutches was more awe-inspiring to vermin than a cat by itself.

These specimens tend to predate the ones Howard concludes were likely foundation sacrifices, which spiked in the sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries—the height of the era of witch trials in England. As fears around witchcraft gained more prevalence, ordinary people thought these concealed cats could protect them from evil forces, whether that meant the evil emanating from the accused witch next door or the evil that could turn an occupant of the house into a witch herself.

Foundation sacrifices, believed by builders and dwellers to appease powers of both good and evil, bringing good fortune onto newly built structures, have been observed historically in cultures spanning the globe. What were once human sacrifices tended to turn toward animal sacrifices later in human history, as religions preaching empathy and laws forbidding murder started to take hold. (Howard notes that in 1950s England, “The custom is still observed of placing coins or other objects under a foundation stone, perhaps as a substitute for the animal sacrifice.”) Although not exclusively buried in foundations, cats found their way into these kinds of sacrifices via their perceived “magical qualities” and reputation as witches’ familiars, which were bolstered by “their nocturnal habits, relative independence, distinctive eyes, and lightning reflexes,” independent researcher Brian Hoggard writes in his new book Magical House Protection: The Archaeology of Counter-Witchcraft. (These ideas likely migrated with the cats themselves from ancient Egypt, where Bastet the cat goddess was worshipped as a protector from disease and evil spirits.) In Western Europe in the later Middle Ages, cats were thought to be representatives of the devil; as a result, the animals were routinely burned in bonfires or drowned in conjunction with major Christian holidays. Yet, somewhat paradoxically, dead cats were also buried in fields to promote a good harvest.

Cats weren’t the only animals or objects buried in walls, ceilings, and floors. Concealed shoes have been by far the most commonly discovered wall secrets, according to Hoggard’s website Apotropaios, devoted to research on “strange things found in walls and under floors.” The shoes, like the dried cats, likely were used to lure evil spirits—“a decoy,” Hoggard says, “having become unique to the wearer’s foot during their life, meaning they would be attacked instead of the person or household.” Marion Gibson, professor of Renaissance and magical literatures at the University of Exeter, adds that the act of burying shoes probably developed out of the tradition of walking around the walls of the house as a means of marking territory. Witch bottles—containers filled with nails, urine, and hair—are often found near doorways and hearths, open spaces where evil spirits might enter the home. Horse skulls frequently would find their way into walls, fireplaces, and under floorboards.

Some of the contradictory beliefs about cats as both protectors from and agents of evil persist hundreds of years later. In Magical House Protection, Hoggard tells the story of a man named Dave Parker, who came across a hidden cat while converting an old stable into apartments in the late 1970s and early 1980s. The foreman on the project told the construction workers to throw the carcass in the dumpster, Hoggard writes, but the workers “all felt deeply superstitious about it and did not want to touch it.” Parker believed it would be bad luck to move the cat but, after the foreman insisted, reluctantly did so. Only minutes later, as he headed back up the steps, “a plaster panel from the ceiling fell down and struck him across the forehead, resulting in a nasty cut. Dave and his friends remained convinced that this happened because he moved the cat.”

Beyond the luck and misfortune of moving previously buried dried cats—at least a few semi-exhumed dried cats are kept in situ with a glass box around them—there remain numerous other superstitions related to cats in cultures the world over, some still bestowing upon the creatures the role of ultimate protector of domestic spaces. In Russia, for example, it’s considered good luck to let a cat walk through a new apartment before moving in as a kind of christening of the space, warding off any lingering evil spirits. In 2014 Russia’s largest bank, Sberbank, came up with a clever publicity stunt: delivering a loaner cat to mortgage clients’ new apartments to cross the threshold first.

But the medieval ancestors of this tradition remain mostly a mystery, despite our attempts to read history onto these animal mummies. As Gibson explains, there’s really no way of knowing what was going through people’s minds when they buried cats in their walls and under their floorboards: “It’s all theory. No one wrote it down.”

Regardless of what the cats might mean, their very existence offers a peek at the past that is missing from the written record. After all, it was the elite who accused members of the lower classes of witchcraft, so any account of people’s beliefs at the time of the witch trials is inevitably skewed toward the upper classes. It is therefore through dried cats and other relics that we can get a more complete picture of the beliefs and superstitions of the time. “These objects are the physical evidence of part of their actual beliefs,” Hoggard told me in an email, “an area which thus far is rarely included in works of history on the topic.”