On a sultry May night in 1940, two dozen Stalinists wearing police and army uniforms, goggles, and fake mustaches approached the villa in Mexico City where Leon Trotsky lived in exile. They disarmed several officers in a nearby police booth. One of the former Soviet leader’s bodyguards stood at the compound’s gate; the posse strode up to him and asked to enter. Once inside, they tossed a homemade bomb into the room of Trotsky’s grandson and fired submachine guns into the bedroom of Trotsky and his wife Natalia. The elderly couple dove to the floor shortly before seventy shots pockmarked their bed and walls.

After twenty minutes, the assailants withdrew. Trotsky and his entourage were virtually unharmed. But the bodyguard who had been on duty at the gate was gone. From where they had been tied up, the real police officers said they had seen him protesting as the shooters marched him to a stolen car and sped off.

Cables flew between Mexico City, Washington, DC, and Moscow in the following days. Nobody was surprised that someone was trying to kill Trotsky, who had been in exile from the Soviet Union since losing a power struggle with Joseph Stalin in 1928. But questions surrounded the missing bodyguard, known to Trotsky and his associates as Bob Shields, a twenty-five-year-old New Yorker from a bourgeois background. His disappearance triggered an investigation involving the Mexican secret police, the U.S. Federal Bureau of Investigation, and Soviet intelligence units.

The case involved an unlikely cast of characters. Shields’ father, Jesse, who claimed J. Edgar Hoover among his acquaintances, immediately flew to Mexico to search for his son. Upon his return, Jesse met with Hoover in Washington, DC, to seek the FBI director’s help in the case. Hoover pledged his assistance but urged Jesse to face the fact that his son had become a fanatic with a pronounced “cause fixation”: a condition Hoover ascribed to “abnormal development.” Mexican authorities fruitlessly scoured the home of Diego Rivera, a onetime friend of Trotsky’s who had feuded with him a year earlier, after rumors spread that the attackers had driven Shields away in the artist’s car.

The mystery would pervade headlines around the world until the successful assassination of Trotsky three months later. Mexican newspapers promoted the theory—decried by Trotsky as a Stalinist misinformation campaign—that Shields was a traitor who had helped organize the abortive assassination. Meanwhile, the police discovered that the raid had been led by another Mexican muralist, David Alfaro Siqueiros, who had fought with Stalinist legions in the Spanish Civil War and was renowned for ghoulish, surrealist paintings such as Portrait of the Bourgeoisie.

As the spring of 1940 turned to summer, Shields remained missing. Trotsky continued to defend his bodyguard’s innocence in public statements, pointing out that Shields could have easily killed him in the weeks before the attack. Privately, though, his staff had many questions. “If he was their agent, why did he do such a clumsy job? His role is very mysterious,” wrote Joseph Hansen, Trotsky’s senior secretary, in a June 20 letter.

Five days later, the mystery would lift slightly. Following a tip about a house that Siqueiros had rented near the Desert of the Lions outside Mexico City, Mexican authorities searched it and exhumed a corpse buried in quicklime beneath the kitchen floor. Trotsky’s other guards recognized Shields’ distinctive curly reddish hair. An autopsy revealed he had been shot twice in the head. Police later learned he had been taken to the house by another artist, Luis Arenal, and Arenal’s brother. Nobody would ever confess to Shields’ murder, however, and the exact circumstances of his death are still not known.

Trotsky wept when he learned of the macabre discovery, which he took as proof of Shields’ innocence. “Poor Bob,” the old man sighed when the news was broken to him by his wife and secretaries. “Poor calumniated Bob.”

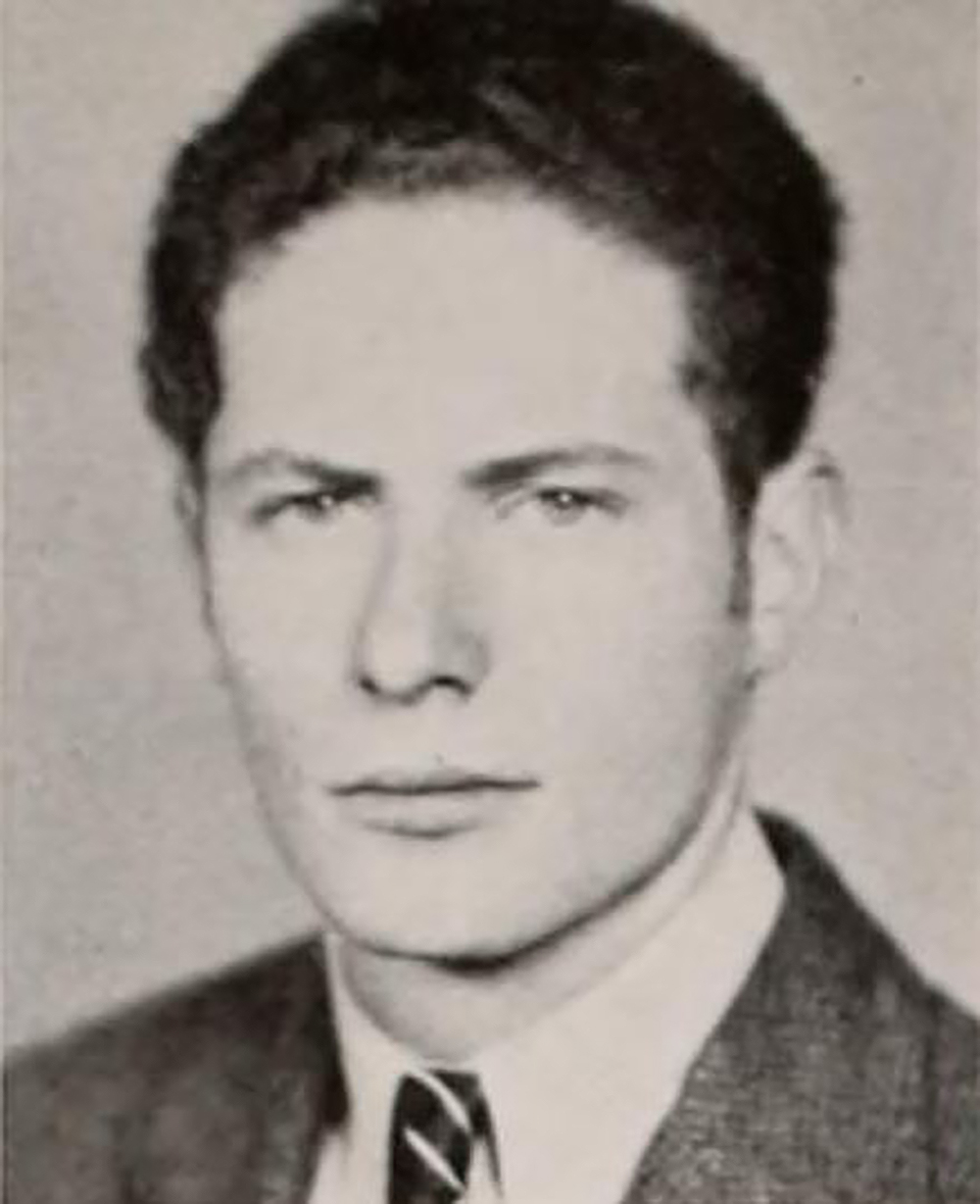

As with the names used by most of Trotsky’s secretaries, “Bob Shields” was a pseudonym. Shields was Sheldon Robert Harte, the scion of a New York City silk-manufacturing magnate—and my father’s second cousin. The story of how he fled a privileged life in Manhattan to advance the proletarian revolution in Mexico is one that trickled down to me, many details incomplete, as I grew up. Tainted on the left by lingering doubts about his loyalty to Trotsky, Sheldon’s public legacy was also stigmatized on the right by the anti-communist tide that swept the United States in the 1940s and ’50s.

My relatives on Sheldon’s branch of the family are still reluctant to discuss his story. My father learned about it only when, as a child, he overheard his father telling a friend. With this meager family apocrypha as my inspiration, I began trying to excavate the truth about Sheldon using public records, government archives, the correspondence of Trotsky and his followers, Sheldon’s own writing, and testimonies from his acquaintances.

Sheldon was born in Brooklyn in 1915, the second child of Jesse and Jessie Hartogensis, a Jewish couple whose parents had immigrated to the United States from Belgium and Germany. They were models of American assimilation. By 1920 the family surname had been shortened to the less conspicuous “Harte” as Jesse worked his way up from jobs in manufacturing and sales management to head a silk-production company. By the time Sheldon was a teenager, the family could afford to send him to an expensive Connecticut boarding school where most students kept pet dogs but Sheldon had a tame monkey. He earned poor grades in high school but was accepted to Duke University in North Carolina.

Eccentricity and rebelliousness were rare at Duke in the 1930s. When Bridget Booher, an editor at the university’s alumni magazine, asked former classmates to share their recollections of Sheldon several decades later for an article about him, the responses revealed much about not only Sheldon but also the campus culture. One alum told Booher he knew Sheldon was a Communist because “most men had short hair and his was wild.” Sheldon helped found Duke’s chapter of the American Students Union, a national anti-war and anti-fascist student organization, prompting an editorial in Duke’s student newspaper that warned of “Marxian sympathizers” on campus.

At Duke Sheldon was known for his tirades against capitalistic ills, such as planned obsolescence, and exclusionary policies like the quotas limiting the number of Jews at U.S. universities. One fellow student who had helped investigate cases for Duke’s Legal Aid Clinic said Sheldon often asked her about social conditions in the American South. “He was appalled by what he saw and heard sometimes but he wanted to know how he could get closer—close enough to ‘know’ what he was aching to write about,” she wrote to Booher.

In his senior year, Sheldon moved into a hut in Duke Forest made of two wooden piano-shipping crates. A friend at Duke later said he guessed Sheldon had chosen such ascetic digs “to use as little as possible of the wealth of his parents produced by the sweat of the oppressed workers.” Next to the shack was a boardinghouse where several law students—including future U.S. president Richard Nixon—resided. In a 1991 letter to Booher, Nixon wrote that he “knew Sheldon Harte at that time,” though schoolwork prevented him from socializing as much as he would have liked with friends, even those who lived close by. Nixon demurred from sharing any details about his friendship with Sheldon but said he would vouch for the accuracy of anything others might recall, “though I may not personally remember it!”

Sheldon wrote prolifically in the quiet shack. In stories, plays, and poems now stored in the Duke University archives, he explored social injustice through myriad perspectives. Some of his first works for Duke’s literary magazine, The Archive, described American veterans of World War I wracked by PTSD and forced to beg on the street. Another was a first-person account of a gay man confined to an asylum. Later, he chronicled a lynching through the eyes of a woman who joins the mob because of her boyfriend and then recognizes the horror of what love has made her do. Some of his efforts to channel the viewpoints of characters on the fringes of his own experience devolved into clichés. But a prodigious insight and interest in human psychology shines through his sometimes hackneyed prose.

One of Sheldon’s last pieces written as an undergraduate, a play about a New York Communist falling out with her lover, a company boss facing a workers’ strike, irked Duke’s dean, who asked one of Sheldon’s English professors to reprimand him. The script was “the kind of thing that might appear in a pinko magazine,” the professor told Booher in 1990. Sheldon, predictably, was unbowed. The professor described him as “a cocky SOB…I decided nothing could be done about it.”

Sheldon vented his frustration with Duke students’ complacency in a final essay in The Archive, published in 1938, six months after his graduation. He blamed their lack of intellectual fervor on the bleak Depression-era opportunities they faced after graduation:

The economic chaos of the present day, like a malignant tumor on the brain, is exerting an overwhelming pressure on our universities, the central nervous system of our civilization. It is spreading its evil in tremors to every nerve and fiber of the body—and its effects are paralyzing!

Sheldon exhorted his peers to resist these stultifying pressures. “Battle with your fears!” he wrote. “There is a cause that will support your faith—you have but to discover it and give it your hearts!”

Back in New York City after graduation, Sheldon discovered his cause when he encountered the Trotsky-aligned Socialist Workers Party at a counterdemonstration at the Madison Square Garden Nazi rally on February 20, 1939. He met Albert Goldman, Trotsky’s lawyer, around the same time, and eventually got a job at a socialist newspaper in New York City. Within a year, he was on the executive committee of the downtown Manhattan branch of the Socialist Workers Party. These activities must have annoyed Sheldon’s father, who would later tell U.S. officials that he had objected to the “radical ideas” of his son.

In March 1940 Sheldon was chosen by Party leaders to join Trotsky’s overstretched staff in Mexico. At lunch with a friend from Duke, he dismissed concerns that it would be a dangerous trip. It was a tremendous opportunity to be with Trotsky, whom he considered one of the greatest writers of all time. He departed New York in early April, a few days before his twenty-fifth birthday, telling his parents he was going to Mexico on a business venture.

Reflecting on Sheldon’s motivations fifty years later, another college friend told Booher he did not think Sheldon cared about the fight between Trotsky and Stalin: “Rather, he wanted to join the worldwide communist conspiracy to wipe out capitalism from the face of the earth and help usher in the workers’ utopia.”

When Sheldon arrived at Trotsky’s compound in the Coyoacán district of Mexico City, he found a summer camp–like atmosphere. Trotsky toiled on his overdue Stalin biography and tended his rabbits and cactus garden. His five bodyguards, who doubled as secretaries, assisted Trotsky while protecting him from the ever-present danger of Stalinist assailants. The guards had received firearms training before coming to Mexico, and practiced regularly. The household ate together and made excursions to the countryside. In his seven weeks at the compound before the May 24 attack, Sheldon was entranced by tales of the Russian Revolution and Trotsky and Natalia’s years in exile, listening “with sparkling eyes” as the couple told him about their past, according to Trotsky’s letters.

The young American and European socialists Sheldon worked with probably informed a play that he wrote in Coyoacán. Strike Scenes follows a group of striking factory workers who face gangsters hired by their boss, nearly lose hope, but ultimately rally. One scene, a fight between the boss and his son, recalled Sheldon’s fraught relationship with his own father. Before quitting his father’s company and storming out, the son in the play declares, “No matter what it costs me, Dad…I’m going to find the truth.”

Strike Scenes is replete with “truths” Sheldon was learning from his new comrades, especially the perils of radical politics. It also foreshadowed the circumstances of his own demise. In the play, company thugs ambush a union leader under a bridge at night and murder him. Describing the incident, one of the characters breaks down: “They clubbed and stabbed him to death…Threw his body in the river…I just seen ’im…(sobs)…ye could hardly tell it was him.”

Mexican authorities arrested Siqueiros four months after the discovery of Sheldon’s corpse. The muralist admitted to helping plan the assault but claimed its purpose was merely to steal Trotsky’s archives and that he had nothing to do with Sheldon’s murder. He was released on bond, fled to Cuba, and spent the rest of his life a free man.

The murdered Sheldon, however, would remain on trial indefinitely. Joseph Hansen described some of the outlandish claims about Sheldon that appeared in Stalin-aligned Mexican newspapers after the attack: Sheldon was Russian, he was a “typical gangster type,” he accepted Stalinist bribes, and more. Such slander was “the moral lime” with which Soviet intelligence sought to “obliterate all the trails leading to the body decomposing in the mountain cabin,” Hansen wrote in an article published that summer in a Socialist Workers Party newsletter.

Siqueiros’ accomplices helped fuel these rumors. One told Mexican authorities that Sheldon had been friendly with one of the non-Mexican plotters, a man they identified as a “French Jew” named Felipe. In fact, “Felipe” was a Lithuanian Jew named Iosif Grigulevich, another Soviet agent and Stalinist veteran of the Spanish Civil War. His identity would not be revealed until the 1990s, in smuggled Soviet intelligence files and the published memoirs of Pavel Sudoplatov, who was deputy director of Soviet foreign intelligence in 1940. Grigulevich had “managed to meet” Sheldon before the attack, according to Sudoplatov, which helped explain why he let in the assailants that night. But Sudoplatov also described opening the gate as a “mistake” on Sheldon's part.

The account of Leonid Eitingon, another Soviet intelligence official who helped mastermind the attack, further clouded Sheldon’s role. In a 1997 volume of essays on Soviet foreign intelligence, Eitingon was quoted saying that Sheldon had been recruited by Soviet agents in New York, but he called Sheldon a traitor. “When the raid participants opened fire, Sheldon told them that if he had known all this, he as an American would never have agreed to participate in the affair,” Eitingon added.

Speculation over Sheldon’s true allegiance divided Trotskyist factions around the world for decades. One person convinced of Sheldon’s duplicity was Esteban Volkov, Trotsky’s grandson, who was fourteen years old during the 1940 attack. In a 2017 interview, Volkov described Sheldon as a Stalinist agent, citing information from the Soviet archives. When I tried to meet Volkov in Mexico City in 2018, I received an email saying he was away, and got no reply to my follow-up questions.

In my family’s collective memory, Sheldon is presumed innocent and mourned as gullible for letting in the attackers. Details of his demise have grown distorted in family retellings. A Harte family history my father received from a second cousin in the 1990s says Sheldon was killed as soon as he opened the gate and that Jesse Harte knew Sheldon was dead before flying to Mexico. Both details are wrong, but what rings true is the grief over his death. “Half a century later, I can still see the anguish in my father’s eyes when he told me how his cousin [Jesse] has to go to Mexico and reclaim the bullet-riddled body of his son,” writes my father’s cousin, inaccurately but poignantly, in the family chronicle. Today Sheldon is buried next to his parents in Beth Olam Cemetery in Queens.

It is impossible to say which account of Sheldon is correct. But his own words provide some clues. The theory that he knowingly assisted a Stalinist plot against Trotsky contradicts the keen sense of social justice that rang through his writing and his friends’ memories of him.

In 1937 Sheldon had written Bitter Herbs, a play about Jews oppressed by Nazis in Germany. He “felt the weight of Hitler terribly,” according to one of his college friends. It is hard to imagine what could have convinced Sheldon to work for Stalin after the Soviet leader signed a nonaggression pact with Hitler in August 1939. The same friend recalled that Sheldon “said to me more than once that the only position to which he felt wedded was pacifism and remarked ironically that, given the rise of fascism, it was a position he found impossible to occupy.”

Like many anti-fascists, Sheldon drew suspicion from both ends of the political spectrum due to his involvement in the socialist movement. Renouncing capitalism pitted him irreparably against his family, causing a rift that never healed. Claims of his Stalinist sympathies would percolate over the decades, leaving his true loyalties hazy. Even the identity that might seem most obviously his—a skeptic of American greatness—was cast in doubt by Eitingon’s claim that Sheldon invoked his American identity to disavow the attack on Trotsky. Perhaps, despite criticizing the United States on many fronts, he had some patriotic pride in American rule of law.

Sheldon’s life would not have been easy had he lived to return to the United States. One year after his death, several of the American Trotskyists who had recruited, trained, and joined him for guard duty in Mexico City would be imprisoned following a FBI raid on the Socialist Workers Party. Federal prosecutors charged the group with conspiracy to overthrow the U.S. government under a 1940 law criminalizing “subversive activity”: a category that had come to encompass anti-war protesting, labor organizing, and expounding the Marxist view that capitalism would inevitably fall. The indictment accused the defendants of using Trotsky’s teachings as their “catechism,” noting that some of them went to Mexico City “to advise with and to receive the advice, counsel, guidance, and directions of the said Leon Trotsky.”

Every American is taught that the United States is an exceptional democracy, founded by radical visionaries overthrowing a tyrannical regime. If there is any truth to the claim that Sheldon described himself as “an American” when denouncing Trotsky’s would-be assassins, I think he was referring to the idealized America often cited by its politicians and chroniclers: a country of freethinking individuals who resist authoritarian violence. In reality, Americans like Sheldon who fit that description—dissidents dedicated to radical reform—are often treated as threats by the same people who most assiduously describe the country as a land of freedom.

Sheldon skewered such incongruities in his writing. In Strike Scenes, he penned a lament for the contradictory nature of authority. Before severing ties with his father over his brutality against the strikers, the boss’ son cries, “You…you taught me to love…The same you who watched men shot down in the street this morning, and only wondered what further means he could find to crush them!”

These words could be aimed at Sheldon’s own father, the capitalist who never accepted his son’s ideals. Or they could be Sheldon’s parting shot to his country: the nation that gave him the freedom, privilege, and education to acquire radical ideals but would never stop fighting efforts to realize them.

Sources

- Socialist Workers Party Records, 1928–2002. Wisconsin Historical Society, Madison, WI.

- Duke University Archives. Durham, NC.

- Leon Trotsky Collection. Hoover Institution Library & Archives, Stanford University, Stanford, CA.

- Leon Trotsky Exile Papers. The Houghton Library, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA.

- National Archives at College Park, College Park, MD.